Pavilion of Human Passions

| Pavilion of Human Passions | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Alternative names | Horta-Lambeaux Pavilion |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | |

| Address | Parc du Cinquantenaire / Jubelpark |

| Town or city | 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°50′35.02″N 4°23′14.48″E / 50.8430611°N 4.3873556°E |

| Current tenants | Saudi Arabia (until 2068)[1] |

| Construction started | 1892 |

| Completed | 1896 |

| Inaugurated | 1 October 1899 |

| Renovated | 2014[2] |

| Cost |

|

| Renovation cost | €800,000[2] |

| Client | Belgian Government |

| Owner | Belgian Government |

| Landlord | Royal Museums of Art and History |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 20 by 15 metres (66 ft × 49 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Victor Horta |

| Other designers | Jef Lambeaux |

| Main contractor | Alphonse Balat[1] |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The Pavilion of Human Passions (French: Pavillon des Passions humaines; Dutch: Paviljoen der Menselijke Driften), also known as the Horta-Lambeaux Pavilion, is a neoclassical pavilion in the form of a Greek temple that was built by Victor Horta in 1896 in the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark of Brussels, Belgium. Although classical in appearance, the building shows the first steps of the young Victor Horta towards Art Nouveau. It was designed to serve as a permanent showcase for a large marble relief The Human Passions by Jef Lambeaux.

Since its completion, the building has remained almost permanently closed. Since 2014, the building is accessible during the summer time.[2]

History

[edit]Inception and construction

[edit]In 1889, Victor Horta was commissioned for 100,000 Belgian francs[1] to design a pavilion to house Jef Lambeaux's sculpture The Human Passions on the recommendation of his teacher Alphonse Balat, King Leopold II's favourite architect.[3][4]

The small pavilion of classical look already announced the Art Nouveau manner associated with the architect. Although loyal to the formal vocabulary of classical architecture, Horta already managed to incorporate all elements of the new style. At first sight, the building looks like a classical temple. However, there is not a single straight line in the building.[5] Every classical detail is revisited and reinterpreted. Horta succeeded in designing an almost "organic" interpretation of the classical temple, without completely abolishing any reference to an historical style.[6] Slightly bent like the foot of a tree, the walls seem to have sprung organically. After World War I, Horta would return to this classicism in his designs for the Centre for Fine Arts and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tournai.

The building, though, has had a turbulent history. The small neoclassical pavilion was originally planned for the 1897 Brussels International Exposition,[7] of which it is one of the few physical remnants. Although completed in time for the fair, the collaboration between the architect and the artist soon led to an irreconcilable disagreement delaying its official opening until 1899. At first, Horta designed the pavilion's façade to be open, serving as a shelter on rainy days — without the wall and bronze doors behind the colonnade — so that the relief would always be visible for passers-by. But Lambeaux, against Horta's will, wanted a gallery wall behind the columns. The dispute remain unsolved for years: on the inauguration day on 1 October 1899, the unfinished temple stood open with the relief visible from the surrounding park. Under pressure of public opinion and the authorities, Horta had to alter his plans and close the temple with a wooden barricade, and it was left unfinished only three days after inauguration.[8]

Lambeaux never knew the pavilion as it currently stands. Shortly after Lambeaux's death, Horta acceded to his wishes by building the wall that would permanently hide the bas-relief with a closed front to enhance the natural light coming through the glass roof.

Later years

[edit]In 1967, the building was given in leasehold for 99 years by King Baudouin to King Faisal ibn Abd al-Aziz of Saudi Arabia, on an official visit to Belgium, together with the East Pavilion of the 1880 National Exhibition that would later become the Great Mosque of Brussels, to house a museum of Islamic art.[notes 1][9] The building and the relief were protected by a royal decree on 18 November 1976. Two years later, the donation to King Khaled of Saudi Arabia was made official by the royal decree of 12 September 1979.

The Saudi Government eventually gave its operation back to the Royal Museums of Art and History.[1] The pavilion remained closed to the public except on occasional open days.[5][10] Since 2002, the pavilion is open one hour per day, except on Mondays.[11] In recent years, this was not due to the public's prudishness, but out of fear for vandalism.[10]

Renovation

[edit]The building was left unattended for more than a century, and by the early 21st century, it required urgent renovation works. In 2008, the Belgian Government officially started contracting out the renovation works by publishing two Government procurements in the Belgian official journal.[12][13] The restoration Jef Lambeaux's work should follow.[11]

Renovation works of the building began in May 2013 and were completed in 2014 for a total cost of €800,000 financed by Beliris. The renovation of the relief itself was finished in 2015.[2]

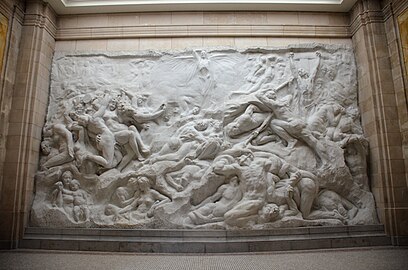

The Human Passions relief

[edit]The Horta pavilion houses the monumental achievement of the sculptor Jef Lambeaux (1852–1908): The Human Passions relief. The draft on paper was presented at the Triennial Salon of Ghent in 1889, creating immediately a big commotion. The journal L'Art Moderne in 1890 described the work as:

(…) a pile of naked and contorted bodies, muscled wrestlers in delirium, an absolute and incomparable childish concept. It is at once chaotic and vague, bloated and pretentious, pompous and empty. (…) And what if, instead of paying for 300,000 francs of "passions", the Government simply bought works of art?[14]

Commissioned in 1890 by King Leopold II for 136,000 francs,[1] the 12 by 8 metres (39 ft × 26 ft) work was centered around the theme of mankind's happiness and sins dominated by death.[6] It also depicted mankind's "negative" passions, such as war, rape and suicide.

The relief had been very controversial ever since the project's presentation in 1886. Although enthusiastic at the beginning, art critics especially regret the work's lack of cohesion.[6] Despite the controversy, the Belgian State acquired the work in 1890 for installation in the Cinquantenaire.[6] Werner Adriaenssens is also inclined to deny the work mythical status:[5]

Sure it is large, as Lambeaux intended, but hardly a masterpiece. The relief consists of separate groups rather than forming a whole. Unfortunately Lambeaux never explained his intentions. Even the title is not his.

On 1 October 1899,[6] Horta's pavilion was officially inaugurated and the work revealed to the public. The unveiled way in which Lambeaux depicted the male and female nude was highly debated in the press. The relief depicting uninhibited nudes in any manner of carnal delights caused scandal. Nudity was not the only problem: the representation of the crucified Christ below Death outraged conservative Belgium.[15] The open building was concealed from public view with a wooden barricade only three days after its first public presentation. Finally, the Government responded to the criticisms by asking Horta to close the front of the building with durable materials in 1906.[9] The front wall came in 1909. The building finally reopened in 1910, without an official opening, and remains unfinished.

The Belgian State ordered a plaster copy of Lambeaux's relief for its display in several World's fairs.[16] The copy is today on display at the Fine Arts Museum of Ghent, Belgium.[17] A fragment of the work won in 1900 a medal of honour at the World's fair of Paris.

-

Detail of the relief made by Jef Lambeaux showcased in the Pavilion of Human Passions

-

At the time as well as much later, the sculpture was deemed indecent.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Art Nouveau in Brussels

- History of Brussels

- Culture of Belgium

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The building belongs legally speaking to the non-profit organization Islamic Cultural Centre of Belgium, of which the ambassador of Saudi Arabia to Belgium is the chairman.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f De Ruyck, Jo (5 April 2012). "Koning Boudewijn vroeg Saudi's om erotisch tafereel te verstoppen". De Standaard (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Duplat, Guy (31 July 2015). "Les passions "scandaleuses" dans le marbre" ["Scandalous" passions in marble]. lalibre.be. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Fowler, Harold (2005). A History of Sculpture. City: Kessinger Publishing. p. 366. ISBN 1-4179-6041-8.

- ^ Celis, Marcel M. (1988). Bruxelles protégé (in French). Liège: Editions Mardaga. p. 41. ISBN 2-87009-335-7.

- ^ a b c Philips, Mon (18 June 2008). "The secrets of Jubelpark" (PDF). Flanders Today (34). Groot-Bijgaarden: Vlaamse Uitgeversmaatschappij: 4. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

Before the Government finally took over the building, it was owned by Saudi Arabia (a gift from King Baudouin).

- ^ a b c d e Musées Royaux d'art et d'histoire. "Pavillon Horta-Lambeaux" (in French). Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Musée des arts décoratifs (France) (1983). Le Livre des Expositions Universelles, 1851–1989 (in French). Paris: Edition des arts décoratifs Herscher. p. 101. ISBN 2-901422-26-8.

- ^ State, Paul (2004). Historical Dictionary of Brussels. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-8108-5075-3.

- ^ a b "Pavillon et relief Les Passions humaines – Parc du Cinquantenaire" (in French). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b Blyth, Derek (6 May 2004). "'Scandalous' sculpture on show at last". The Bulletin (Brussels weekly). Brussels.

- ^ a b Leclercq, Philippe (20 October 2008). "Passions Humaines.Le mot de Werner Adriaenssens" (in French). asbl Musée Jef Lambeaux. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- ^ SPF Mobilité et Transports (23 July 2008). "Parc du Cinquantenaire — Pavillon Horta — restauration des décors en plaques de marbre jaune — Marché de travaux — Appel à candidature (TIW/IX.8.8.)" (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ SPF Mobilité et Transports (25 August 2008). "Parc du Cinquantenaire — Pavillon Horta — restauration du bâtiment — Marché de travaux — Adjudication publique (TIW/IX.8.9.)" (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Maus, Octave; Picard, Edmond; Verhaeren, Emile, eds. (25 May 1890). "Une commande de 300 000 francs". L'Art Moderne (in French). Brussels: 166. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Tumanov, Alexander (2000). The Life and Artistry of Maria Olenina-D'alheim. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-88864-328-4.

(…) There we had got to know (…) Joseph Lambeaux, a sculptor who was famous at the time. (…) When Joseph Lambeaux had completed his enormous work in high relief entitled "Passions Humaines" King Leopold wanted to see it and came to Lambeaux's studio. Observing that the crucified Christ was placed lower than Death, which reigned over everyone, he asked the sculptor to make the necessary adjustment and place Christ above Death. But Joseph said modestly,"Your Highness, that is how I see and feel it. I cannot alter it." Nor did he. He was something of an excentric. (…)

- ^ Duplat, Guy (29 November 2008). "Jef Lambeaux, le sulfureux". La Libre Belgique. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Vlaamse Kunstcollectie. "Copy in gypse of Jef Lambeaux's Human passions De menselijke driften". Photography (in Dutch). Museum of Fine Arts Ghent. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 106.

- de Callataÿ, François (1989). "Les "Passions Humaines" de Jef Lambeaux: un essai d'interprétation". Bulletins des Musées Royaux d'Arts et d'Histoire (in French). 60. Brussels: Musées Royaux d'Arts et d'Histoire: 269–289.

- Celis, Marcel M. (1988). Bruxelles protégé (in French). Liège: Editions Mardaga. p. 41. ISBN 2-87009-335-7.

- Aubry, Françoise; Harshav, Barbara (2002). "Victor Horta: Vicissitudes of a Work". Yale French Studies (102). New Haven: 176–189. doi:10.2307/3090599. JSTOR 3090599.

- Musées Royaux d'art et d'histoire. "Pavillon Horta-Lambeaux" (in French). Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- SPF Mobilité et Transports (23 July 2008). "Parc du Cinquantenaire — Pavillon Horta — restauration des décors en plaques de marbre jaune — Marché de travaux — Appel à candidature (TIW/IX.8.8.)" (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- SPF Mobilité et Transports (25 August 2008). "Parc du Cinquantenaire — Pavillon Horta — restauration du bâtiment — Marché de travaux — Adjudication publique (TIW/IX.8.9.)" (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Blyth, Derek (6 May 2004). "'Scandalous' sculpture on show at last". The Bulletin (Brussels weekly). Brussels.

A 'shocking' sculpture which has been kept behind locked doors for more than a century is finally on view in the Parc du Cinquantenaire. Jef Lambeaux's marble relief of Les Passions Humaines — carved in 1899 for a neo-classical temple built by the young Victor Horta — outraged conservative Belgium when it was unveiled and the building was closed to the public after just two days.

Further reading

[edit]- Cuypers, Carine (2012). Het paviljoen van de Menselijke Driften (in Dutch). CaraCarina. ISBN 978-94-91483-00-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pavilion of Human Passions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pavilion of Human Passions at Wikimedia Commons- "Slideshow — Pavillon Lambeaux-Horta : Les Passions humaines" (in French). 2005. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

![At the time as well as much later, the sculpture was deemed indecent.[citation needed]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/The_Human_Passions_%28Happiness%29_-_Jef_Lambeaux.jpg/407px-The_Human_Passions_%28Happiness%29_-_Jef_Lambeaux.jpg)