Somuk

Somuk | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1900 Gagan, Buka Island, German New Guinea |

| Died | 1965 Buka Island, Territory of New Guinea |

| Style | Drawing |

| Movement | Folk art Art brut |

Somuk (c. 1900–1965), also known as Herman or Hermano Somuk, was an artist and cultural leader from Buka Island in what is now the Autonomous Region of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea. He is known for his depictions of Buka Island cultural traditions and mythology, as well as events during the Japanese invasion of Buka during World War II.

Biography

[edit]

Somuk was born around 1900 on Buka Island, part of the Northern Solomon Islands in what was then German New Guinea.[1][2] He was a speaker of the Solos language and remained "faithful to the rich traditions and ceremonial practices" taught by his father Parebuin.[3] He was a member of the Naboin clan.[4]

Somuk lived most of his life in the village of Biroat on the mountainous west coast of Buka Island, near the village of Gagan where there was a French mission. He attended the local mission school where he was educated by nuns and influenced by the local Marist priest, Father Lukan, who encouraged him to draw.[4] He became a catechist and was reputedly one of the first individuals in Gagan to learn to read and write.[5]

In January 1935, Somuk encountered Patrick O'Reilly, a French Catholic priest who had been trained in ethnology and dispatched to the Solomon Islands and New Guinea to collect materials for the Musée de l'Homme in Paris.[6] O'Reilly cultivated Somuk as an informant and encouraged him to depict cultural stories on paper, supplying him with ink and coloured pencils. Somuk remained in contact with O'Reilly after he returned to France and continued to send him artworks via the Marist missionaries.[7]

Somuk was a tribal leader and in his home district "his reputation as a chief and as the first literate person in the area took precedence" over his artwork. After his death local residents recalled that he had "played a major political role in the first decades of the colonial period".[8] Somuk refused to work as a plantation labourer, unlike many others, and instead earned a living by farming, performing church duties and selling his artwork.[4] O'Reilly recalled him as a "Solomonese dandy", who wore a non-traditional calico lavalava, a necklace made of bats' teeth, and stained his hair with ochre.[9] He travelled widely through Buka Island and neighbouring Bougainville Island, as far south as Torokina.[10] He died in Gagan in 1965.[4]

Artwork

[edit]Themes and analysis

[edit]

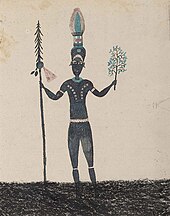

Somuk's drawings "provide one of the only glimpses of life in Bougainville during the early colonial period from an indigenous perspective".[4] He worked primarily in crayon, pencil and ink, although some sculptures – including meeting house panels – have also been attributed.[11] His depictions of humans, animals and plants are characterised by the use of silhouetted figures rendered in black crayon, which have been linked to a pre-colonial style found widely on Buka.[4]

One of Somuk's earliest surviving drawings, dated to around 1930 before O'Reilly's influence, depicts a man wearing an upe (traditional headdress) as well as other traditional items and tools. It has been suggested that his drawings of traditional clothing and tools can be "interpreted as an attempt to preserve the Solos peoples' ceremonies that were being interrupted and overtaken".[3] Another drawing is said to depict the origins of trees and plants and their relation to human genealogy.[12]

O'Reilly in 1951 described his works as the "Bayeux Tapestry of the Solomonese archipelago" in their use of episodic imagery.[13] One series of drawings documents "the death and passage to the afterlife" of Guérian, a possibly mythical ancestor figure. Guérian is depicted wearing an upe, kapkap (shell ornament), and shell money, accompanied on his journeys by a series of animals.[3]

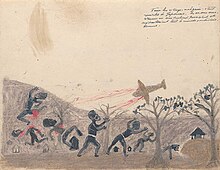

Several of Somuk's works depict events from the Japanese invasion of Buka during World War II. One crayon drawing shows Indigenous workers wearing lap-laps undertaking forced labour under Japanese supervisors, likely depicting the construction of an airfield. Another drawing shows the Allied bombing of Buka Island during the Bougainville campaign, which had a "devastating impact on local populations" both from direct fatalities and from starvation and disease as residents fled to the island's forests and caves.[3]

Exhibitions and collections

[edit]

In the late 1940s, O'Reilly's collection of Somuk's drawings came to the attention of Jean Dubuffet, who had originated the term art brut. Dubuffet and Jean Paulhan organised exhibitions at the galleries of Gaston Gallimard and René Drouin,[7] while in 1951 O'Reilly organised his own exhibition at the Galerie des Iles.[14]

As of 2019[update], 92 drawings by Somuk had been identified, almost all of which are held by European institutions.[8] Around 50 drawings were included in a collection of O'Reilly's papers donated to the Marist archives in Rome after his death in 1988, which were not identified as Somuk's until 2016.[15] Another 20 drawings are held in one of O'Reilly's scrapbooks, which was acquired by the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. Eleven drawings were donated by O'Reilly to the Musée de l'Océanie in La Neylière, near Lyons, while three drawings were acquired by Dubuffet from O'Reilly for his Collection de l'art brut in Lausanne, Switzerland.[8]

In 2012, an art project was developed by the Red Cross and the University of Papua New Guinea where residents of Bougainville were introduced to Somuk's drawings and asked to produce their own artwork reflecting their experiences of the Bougainville crisis.[16] In 2020, the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris hosted an exhibition of Somuk's art titled le premier artiste moderne du Pacifique ("The First Modern Artist of the Pacific").[17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Herman Somuk". QAGOMA. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Reyssat, Sophie (25 March 2021). "Hermano Somuk, le dessinateur-conteur des îles Salomon au musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac". La Gazette Drouot (in French). Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Women's Wealth". QAGOMA. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f McDougall 2018, p. 159.

- ^ Garnier, Nicolas (2019). "Somuk: The First Modern Artist of the Pacific". Tribal Art Magazine. 94: 142–143.

- ^ Garnier 2022, pp. 311–326.

- ^ a b Wohlfarth, Bettina (8 February 2020). "Zwischen Ethnographie und Art brut". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Garnier 2019, p. 143.

- ^ Montauban & O'Reilly 1952, p. 42.

- ^ McDougall 2018, p. 161.

- ^ Garnier 2019, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Roué, Marie (2003). "ONG, peuples autochtones et savoirs locaux: enjeux de pouvoir dans le champ de la biodiversité". Revue internationale des sciences sociales (in French) (178): 599. doi:10.1016/S1240-1307(03)00014-1.

- ^ Brun 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Brun, Baptiste (2014). "Réunir une documentation pour l'Art Brut : les prospections de Jean Dubuffet dans l'immédiat après-guerre au regard du modèle ethnographique". Les Cahiers de l'École du Louvre (in French). 4: 64. doi:10.4000/cel.487.

- ^ Garnier 2022, p. 322.

- ^ "Images of the Crisis". QAGOMA. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Kelviel, Sylvie (18 January 2020). "Somuk, chroniqueur pacifique". Le Monde. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Garnier, Nicolas (2022). "Artefacts without Fieldnotes: the Bougainville collection from Patrick O'Reilly". Journal de la Société des Océanistes. 155 (155): 311–326. doi:10.4000/jso.14307.

- McDougall, Ruth (2018). "Somuk, Moah and images of the crisis". In Saines, Chris (ed.). The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. QAGOMA. pp. 158–161. ISBN 9781921503924.

- Montauban, Paul; O'Reilly, Patrick (1952). "Mythes de Buka: Iles Salomon". Journal de la Société des Océanistes (in French). 8: 27–80.