Sharifian Solution

The Sharifian or Sherifian Solution (Arabic: الحلول الشريفية) was an informal name for post-Ottoman British Middle East policy and French Middle East policy of nation-building. As first put forward by T. E. Lawrence in 1918, it was a plan to install the three younger sons of Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi (the Sharif of Mecca and King of Hejaz) as heads of state in newly created countries across the Middle East, whereby his second son Abdullah would rule Baghdad and Lower Mesopotamia, his third son Faisal would rule Syria, and his fourth son Zeid would rule Upper Mesopotamia. Hussein himself would not wield any political power in these places, and his first son, Ali would be his successor in Hejaz.[2]

Given the need to rein in expenditure and factors outside British control, including France's removing of Faisal from Syria in July 1920, and Abdullah's entry into Transjordan (which had been the southern part of Faisal's Syria) in November 1920, the eventual Sharifian solution was somewhat different, the informal name for a British policy put into effect by Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill following the 1921 Cairo conference. Faisal and Abdullah would rule Iraq and Transjordan respectively; Zeid did not have a role, and ultimately it proved impossible to make satisfactory arrangements with Hussein and the Kingdom of Hejaz. An underlying idea was that pressure might be applied in one state to secure obedience in another;[3] as it transpired, the inherent assumption of family unity was misconceived.[4]

Antonius' The Arab Awakening (1938) later disparaged Lawrence's claim in his Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926) that Churchill had "made straight all the tangle" and that Britain had fulfilled "our promises in letter and spirit".[5]

Abdullah was assassinated in 1951, but his descendants continue to rule Jordan today. The other two reigning branches of the dynasty did not survive; Ali was ousted by Ibn Saud after the British withdrew their support from Hussein in 1924/25, while Faisal's grandson Faisal II and Ali’s son Abd al-Ilah were executed in the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état.

The "tangle"

[edit]Failure in Syria

[edit]Faisal was the first of Hussein's sons to gain an official role, in OETA East, a joint Arab-British military administration. The Arab and British armies entered Damascus on 1 October 1918, and on 3 October 1918 Ali Rida al-Rikabi was appointed Military Governor of OETA East.[6][7] Faisal entered Damascus as of 4 October and appointed Rikabi Chief of the Council of Directors (i.e. prime minister) of Syria. The territory consisted of the Ottoman Damascus Vilayet and the southern part of the Aleppo Vilayet. The area of Ma'an and Aqaba became subject of a dispute.[8]

Faisal consistently maintained that the Sykes-Picot Blue Zone was part of the area promised to Hussein in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence.[9] On 15 September 1919, Lloyd George and Clemenceau reached an agreement whereby British forces were to be withdrawn starting on 1 November. As a result, OETA East became a sole Arab administration on 26 November 1919.[10]

In the meantime, Faisal was called to London, arriving there on 18 September and it was ultimately explained to him that he would have to make the best of it that he could with the French.[11] While in London, Faisal was given copies of all of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence that until then he had not been fully apprised of; according to his biographer, Faisal believed that he had been misled by his father and by Abdullah in this regard.[12][13] Faisal arrived in Paris on October 20.[14]

Faisal and Clemenceau finally agreed on 6 January 1920, that France would permit limited independence of Syria with Faisal as king provided Syria remained under French tutelage, Syria to accept the French mandate and control of Syria's foreign policy.[15]

The political scene in Damascus was dominated by three organizations, al-Nadi al-'Arabi (the Arab Club with strong Palestinian connections), Hizbal-Istiqlal al-'Arabi (the Arab Independence Party connected to al-Fatat) and Al-'Ahd (an Iraqi-run officers association).[16]

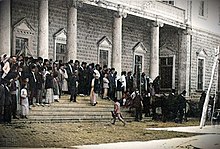

On the steps of the Arab Club building

After returning to Damascus on 16 January, Faisal then proved unable to convince these supporters of the merits of his arrangement with Clemenceau and the Syrian National Congress on 8 March 1920 declared Faisal King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria over the whole of the OETA East area, and nominally over the rest of the historical region of Syria (which included Palestine). Jointly with the French, Lord Curzon disapproved and asked Faisal to take up his case with the Supreme Council.[17][18] Curzon met with the French ambassador on 30 March and noted that the £100K monthly Anglo-French subsidy to Faisal had not been paid since the end of 1919 and should not be paid if Faisal pursues an "unfriendly and independent policy".[19]

In April 1920 the San Remo conference handed the French a Mandate for Syria; Faisal was invited to attend but did not do so, Nuri al-Said, Rustam Haidar and Najib Shuqayr attended informally, arriving nearly a week late and remained isolated from the main decisions of the conference.[20]

On 11 May, Millerand (who had replaced Clemenceau on 20 January) wrote:

...the French government could not agree any longer to the daily violation of the principles of the agreement accepted by the Emir... Faysal cannot be at one and the same time representative of the king of Hejaz, of Pan-Arab claims and prince of Syria, placed under French mandate.

According to Friedman, on 26 April 1920, Hussein told Allenby that he claimed the exclusive right of representation at the Peace Conference, that he appointed Abdullah to replace Faisal and on 23 May 1920, he cabled to Lloyd George "in view of the decisions taken by the Syrian Congress, Faisal cannot speak on Syria's behalf."[21]

The Arab Kingdom of Syria ceased to exist on 25 July 1920 following the Franco-Syrian War and the Battle of Maysalun.[22]

Mandates, money and British politics

[edit]During 1920 Britain's Middle East policies were frequently debated. There were MPs who knew the area, giving Parliament the means to question policy.[23] Paris mentions that there many examples of Parliamentary debate of Britain's Palestine policy.[24][25]

The British were intent on securing Arab, in particular, Hussein's approval of the Mandates, especially the Palestine Mandate. Hussein had not ratified Versailles nor had he signed Sèvres or otherwise accepted the Mandates. Hussein's signature could have quieted the parliamentary factions that repeatedly alleged unfulfilled pledges to the Arabs. This undermined the fragile structure of Churchill's Sherifian solution that was partially based on the idea of a web of family relationships.[26]

In his role as Secretary of State for War, Churchill had since 1919 been arguing for withdrawal from the Middle East territories since it would involve Britain "in immense expense for military establishments and development work far exceeding any possibility of return" and in 1920 in regards to Palestine "The Palestine venture is the most difficult to withdraw from and the one which will certainly never yield any profit of a material kind."[27]

On 14 February 1921, Churchill took over at the Colonial Office tasked with making economies in the Middle East. He arranged for the conference at Cairo with a view to this end as well as making an Anglo-Arab settlement.[28]

Cairo and Jerusalem

[edit]Besides Churchill and Lawrence, the delegates included Percy Cox and Herbert Samuel as well as Gertrude Bell and two Iraqis, Ja'far al-Askari, well known to Faisal, and Sasson Hesqail, the interim defense and finance ministers[29] respectively in Iraq at the time.[30] On 23 March Churchill left for Jerusalem and was headed back to London on 2 April.[31]

In the course of a report to parliament on 14 June 1921 that dealt with the outcomes of the conference, Churchill said:

We are leaning strongly to what I may call the Sherifian solution, both in Mesopotamia, to which the Emir Feisal is proceeding, and in Trans-Jordania, where the Emir Abdulla is now in charge. We are also giving aid and assistance to King Hussein, the Sherif of Mecca, whose State and whose finances have been grievously affected by the interruption of the pilgrimage, in which our Mohammedan countrymen are so deeply interested, and which we desire to see resumed. The repercussion of this Sherifian policy upon the other Arab chiefs must be carefully watched.[32]

Meetings with Abdullah

[edit]

Standing first row: from left: Gertrude Bell, Sir Sassoon Eskell, Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, Jafar Pasha al-Askari

Abdullah had appointed Sharif 'Ali bin al-Husayn al-Harithi as an emissary to go North on his behalf and Rudd notes that by early February 1921 the British had concluded that "the Sherif's influence has now completely replaced that of the local governments and of the British advisers in Trans-Jordania, and [that] it must be realised that if and when Abdullah does advance northwards in the spring, he will be considered by the majority of the population to be the ruler of that country.".[33] Abdullah arrived in Amman on 2 March and sent Awni Abd al-Hadi to Jerusalem to reassure Samuel who insisted that Transjordan could not be used as a base from which to attack Syria and asked that Abdullah await Churchill's arrival at Cairo.[34]

Between 28 and 30 March, Churchill had three meetings with Abdullah.[35] Churchill proposed to constitute Transjordan as an Arab province under an Arab Governor, who would recognise British control over his Administration and be responsible to the High Commissioners for Palestine and Transjordan. Abdullah argued that he should be given control of the entire area of Mandate Palestine responsible to the High Commissioner. Alternatively he advocated a union with the territory promised to his brother (Iraq). Churchill rejected both demands.[36]

Responding to Abdullah's fear for a Jewish kingdom west of the Jordan, Churchill decreed it was not only not contemplated "that hundreds and thousands of Jews were going to pour into the country in a very short time and dominate the existing population", but even was quite impossible. "Jewish immigration would be a very slow process and the rights of the existing non-Jewish population would be strictly preserved." "Trans-Jordania would not be included in the present administrative system of Palestine, and therefore the Zionist clauses of the mandate would not apply. Hebrew would not be made an official language in Trans-Jordania, and the local Government would not be expected to adopt any measures to promote Jewish immigration and colonisation." About British policy in Palestine, Herbert Samuel added that "There was no question of setting up a Jewish Government there ... No land would be taken from any Arab, nor would the Moslem religion be touched in any way."[37]

The British representatives suggested that if Abdullah were able to control the anti-French actions of the Syrian Nationalists it would reduce French opposition to his brother's candidature for Mesopotamia, and might even lead to the appointment of Abdullah himself as Emir of Syria in Damascus. In the end, Abdullah agreed to halting his advance towards the French and to administer the territory east of the Jordan River for a six-month trial period during which he would be given a British subsidy of £5,000 per month.[38]

Transjordan

[edit]

The region, which would become part of Transjordan, was separated from the area of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon after the French defeated King Faisal in July 1920.[39] For a time, the area had no established ruler nor occupying power.[40] Norman Bentwich wrote that "The Arabs were left to work out their destiny" after the British did not send troops or an administration.[41] Herbert Samuel wrote that the region was "left politically derelict".[42][43]

On 7 September, Rufaifan al-Majali (al-Karak) and Sultan al-'Adwan (al-Balqa), both supporters of the British, received telegrams from Hussein announcing that one of his sons was coming north to organize a movement to oust the French from Syria. Abdullah arrived in Ma'an on 21 November 1920 leaving on 29 February 1921 and arriving in Amman on 2 March 1921.[44]

Abdullah established his government on 11 April 1921.[45]

Iraq

[edit]Abdullah's Iraq ambitions

[edit]On the same day as Faisal was proclaimed King of Syria, Al-'Ahd convened the Iraqi Congress (a congress of 29 Iraqis in Damascus that included Ja'far al-Askari as well as his brother-in-law Nuri al-Said), at which they called for the independence of Iraq, with Abdullah as king and Zayd as his deputy; as well as the eventual union of Iraq with Syria.[a] The Iraqi revolt against the British began a few weeks later at the end of June 1920.[48]

Faisal's Iraq ambitions

[edit]Following the fall of the Arab Kingdom of Syria, Faisal made his way via Haifa (1 to 18 August) to Italy, arriving in Naples on 25 August 1920. En route, 'Abd al-Malik al-Khatib, the Hejaz representative in Egypt, gave Faisal a letter from Hussein saying that Faisal should only discuss policy with the British government and only on the basis of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence while also reproving Faisal for "declaring a separate kingdom and not being content to remain as Hussein's representative".[49][21] According to the director of the Arab Bureau, reporting on the discussions between Faisal and 'Abd al-Malik, in regards to Iraq "...If the British government wished him to go he was ready either as ruler or as regent for Abdullah..."[50][51]

Faisal headed for Switzerland where Lloyd George was vacationing but was dissuaded from doing so by a message from the British asking him to wait for an invitation to England, so he went instead to Lake Como and remained there for the next three months.[52]

In November Hussein appointed Faisal as head of Hejaz delegation in Europe, and left for England on 28 November.

Faisal in England

[edit]Faisal arrived in England on 1 December[53] and had an audience with King George on 4 December.[54] In response to early British concerns, Faisal in early December, sent cables to Hussein requesting his intervention with Abdullah to not upset the London discussions with threats of action against the French.[55][56]

On 9 December, according to Faisal's biographer, Haidar recorded in his diary "We had lunch with Lawrence and Hogarth...It would appear from Lawrence's statements that Britain will act in Iraq. He [Lawrence] asked our Lord [Faisal] about his views. There is no doubt that at heart he [Faisal] wants this [position] even if it would lead to conflict with his family."[57]

After receiving authorization on 19 December from Hussein to enter into official discussions, Faisal, together with Haidar and General Gabriel Haddad,[58] met on 23 December with Sir John Tilley, Hubert Young and Kinahan Cornwallis. In this meeting, there was a frank exchange of views wherein Tilley, representing Curzon, raised the issue of Hussein's signature to Sèvres and Faisal explained that Hussein would not sign until he was sure about Britain's intention to fulfill its promises to him. There were discussions about the McMahon-Hussein correspondence and its meaning and an agreement to set out English and Arabic versions side by side to see if anything might be resolved.[59][60][61]

The next day[62] the English and Arabic texts of were compared. As one official, who was present, put it,[63]

In the Arabic version sent to King Husain this is so translated as to make it appear that Gt Britain is free to act without detriment to France in the whole of the limits mentioned. This passage of course had been our sheet anchor: it enabled us to tell the French that we had reserved their rights, and the Arabs that there were regions in which they would have eventually to come to terms with the French. It is extremely awkward to have this piece of solid ground cut from under our feet. I think that HMG will probably jump at the opportunity of making a sort of amende by sending Feisal to Mesopotamia.[b]

Paris cites Kedourie[65] to claim that Young's translation was at fault, that "Young, Cornwallis and Storrs all appear to have been mistaken"[66] and Friedman asserts that the Arabic document produced by Faisal was "not authentic", a "fabrication".[67]

In early January, Faisal was given a print, ordered by Young, of the "Summary of Historical Documents from...1914 to the out-break of Revolt of the Sherif of Mecca in June 1916," dated 29 November 1916.[68] Young on 29 November 1920 had written a "Foreign Office Memorandum on possible negotiations with the Hedjaz," addressing the intended content of a treaty,[69] interpreting the Arabic translation to be referring to the Vilayet of Damascus. This was the first time an argument was put forward that the correspondence was intended to exclude Palestine from the Arab area.[61]

On 7 January and into the early hours of 8 January, Cornwallis, acting informally with instructions from Curzon, sounded out Faisal on Iraq. While agreeing in principle to a mandate and not to intrigue against the French, Faisal was equivocal about his candidacy: "I will never put myself forward as a candidate"...Hussein wants "Abdullah to go to Mesopotamia" and "the people would believe I was working for myself and not for my nation." He would go "if HMG rejected Abdullah and asked me to undertake the task and if the people said they wanted me". Cornwallis thought that Faisal wanted to go to Mesopotamia but would not push himself or work against Abdullah.[70][71][72]

On 8 January, Faisal joined Lawrence, Cornwallis, The Hon. William Ormsby-Gore, MP and Walter Guinness MP at Edward Turnour, Earl Winterton's country house for the weekend. Allawi quotes Winterton's memoirs in support of the claim that Faisal agreed after many hours of discussions to become King of Iraq.[73] Paris says that Winterton had been approached by Philip Kerr, Lloyd George's private secretary, with a message that the prime minister "was prepared to offer the crown of Iraq to...Faisal if he will accept it. He will not offer it unless he is sure of the Emir's acceptance." Paris also says that the meeting and its results were kept secret.[74]

On 10 January, Faisal met with Lawrence, Ormsby Gore and Guinness. Allawi says that upcoming changes in the department responsible for British Middle Eastern policy were discussed along with the situation in the Hejaz. Faisal continued to demur as regards Iraq, preferring that Britain should put him forward. Lawrence later reported to Churchill on the meeting, but could not yet confirm that Faisal would accept the nomination for Iraq if the British government made him a formal offer.[73]

Faisal and Haddad met Curzon on 13 January 1921. Faisal was concerned about ibn Saud and sought to clarify the British position as the India Office appeared supportive of him. Curzon thought that Hussein threatened his own security by refusing to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Faisal requested arms for the Hejaz and reinstatement of the subsidy but Curzon declined.[75]

Lawrence, in a letter to Churchill on 17 January 1921, wrote that Faisal "had agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine" in return for Arab sovereignty in Iraq, Trans-Jordan and Syria. Friedman refers to this letter as being from Lawrence to Marsh (Churchill's private secretary), states that the date of 17 January is erroneous ("a slip of the pen, or a misprint") and claims that the most likely date is 17 February. Friedman as well refers to an undated ("presumably 17 February") letter from Lawrence to Churchill that does not contain this statement.[76] Paris references only the Marsh letter and while claiming the evidence is unclear, suggests that the letter may have described a meeting that took place shortly after 8 January at Earl Winterton's country house.[77] On 20 January, Faisal, Haddad, Haidar, Young, Cornwallis and Ronald Lindsay met. Faisal's biographer says that this meeting led to a misunderstanding that would later be used against Faisal as Churchill later claimed in parliament that Faisal had acknowledged that the territory of Palestine was specifically excluded from the promises of support for an independent Arab Kingdom. Allawi says that the minutes of the meeting show only that Faisal accepted that this could be the British government interpretation of the exchanges without necessarily agreeing with them.[78]In parliament, Churchill in 1922 confirmed this, "...a conversation held in the Foreign Office on the 20th January, 1921, more than five years after the conclusion of the correspondence on which the claim was based. On that occasion the point of view of His Majesty's Government was explained to the Emir, who expressed himself as prepared to accept the statement that it had been the intention of His Majesty's Government to exclude Palestine."[79]

Rudd says that, in regards to Iraq, Lindsay commented in his record of the meeting that "If he is a member of the Sherifian family we should welcome him. If it is Abdullah well and good. If Feisal—perhaps better."[80]

The 7 December draft of the Mandate for Palestine was published in The Times on 3 February 1921 and according to Paris, Faisal made a formal protest to Curzon on 6 January, the gist of which was also published in the Times on 9 February.[81] According to historian Susan Pedersen, Faisal also on 16 February, filed a petition to the League of Nations on behalf of his father, that the situation violated wartime pledges as well as Article 22 of the Covenant. The petition was ruled "not receivable" on the "dubious" grounds that a peace treaty had not been signed with Turkey.[82]

On 16 February Faisal met Lawrence and Allawi quotes Lawrence as saying "I explained to him that I had just accepted an appointment in the Middle Eastern Department of the Colonial Office...I then spoke of what might happen in the near future, mentioning a possible conference in Egypt...in which the politics, constitution and finances of the Arabic areas of Western Asia would come in discussion...These were all of direct interest to his race, and especially to his family, and I thought present signs justified his being reasonably hopeful of a settlement satisfactory to all parties."[83] Karsh gives a similar report and while reporting on the Marsh letter, does not connect it to this meeting.[84] This meeting is determined by Friedman to be the meeting subject of the undated letter from Lawrence to Marsh.[85]

On 22 February Faisal met Churchill, with Lawrence interpreting. As recorded by Lawrence, Faisal's acceptance of the Mandate and a promise not to intrigue against the French were not explicitly agreed upon. Faisal asked Churchill about the mandate and while he considered the Mandate as important Faisal did express doubts about what a Mandate would entail. The meeting concluded with Churchill telling Faisal that 'things might be arranged' by 25 March and that Faisal should remain in London 'in case his advice or agreement was needed'.[86]

On 10 March Faisal's submitted the Conference of London—Memorandum Submitted to the Conference of Allied Powers at the House of Commons.[87] Faisal had written to Lloyd George on 21 February to reiterate Hussein's position on Sèvres and to ask that a Hejazi delegation be allowed to attend. Lloyd George tabled the letter at the meeting but the French objected and only finally agreed to receive a submission form Haddad on Faisal's behalf.[88]

The Cairo conference having opened on 12 March and deliberated Faisal's candidature for Iraq, on March 22 Lloyd George told Churchill that the Cabinet were "..much impressed by collective force of your recommendations ... and it was thought that order of events should be as follows:"

Sir P. Cox should return with as little delay as possible to Mesopotamia, and should set going the machinery which may result in acceptance of Feisal's candidature and invitation to him to accept position of ruler of Irak. In the meantime, no announcement or communication to the French should be made. Feisal, however, will be told privately that there is no longer any need for him to remain in England, and that he should return without delay to Mecca to consult his father, who appears from our latest reports to be in a more than usually unamiable frame of mind. Feisal also will be told that if, with his father's and brother's consent, he becomes a candidate for Mesopotamia and is accepted by people of that country, we shall welcome their choice, subject, of course, to the double condition that he is prepared to accept terms of mandate as laid before League of Nations, and that he will not utilise his position to intrigue against or attack the French ... If above conditions are fulfilled, Feisal would then from Mecca make known at the right moment his desire to offer himself as candidate, and should make his appeal to the Mesopotamian people. At this stage we could, if necessary, communicate with the French, who, whatever their suspicions or annoyance, would have no ground for protest against a course of action in strict accordance with our previous declarations.[89]

Lawrence cabled Faisal on 23 March: "Things have gone exactly as hoped. Please start for Mecca at once by the quickest possible route... I will meet you on the way and explain the details."[90] Faisal left England at the beginning of April.

Back home

[edit]At Port Said on 11 April 1921, Faisal met Lawrence to discuss the Cairo conference and way ahead. Of the meeting, Lawrence wrote to Churchill that Faisal promised to do his part and guaranteed not to attack or intrigue against the French. Faisal once again expressed reservations about the Mandate.[91]

Faisal reached Jeddah on 25 April and after consultations with Hussein in Mecca and making preparations for his upcoming arrival in Iraq, departed on 12 June for Basra. With him were Iraqis who had taken refuge in the Hejaz after the 1920 rebellion and were now returning as part of the amnesty that had been declared by the British authorities in Iraq along with his own close group of advisers, including Haidar and Tahsin Qadri. Cornwallis, his newly appointed adviser was also there.[92]

Faisal's ascendancy

[edit]

Faisal arrived in Basra on 23 June 1921, his first time ever in Iraq, and was to be crowned King just two months later on 23 August 1921.[93]

Hussein and the Hejaz

[edit]Reduction and end of subsidy

[edit]Having received £6.5m between 1916 and April 1919, in May 1919 the subsidy was reduced to £100k monthly (from £200k), dropped to £75K from October, £50k in November, £25k in December until February 1920 after which no more payments were made. After Churchill took over the Colonial Office, he was supportive of the payment of subsidies and argued that given the projected financial savings in Iraq, an amount of £100k was not exceptional and even, in view of the Sherifian plan, that Hussein ought to receive a larger amount than Ibn Saud. This was an issue that the Cabinet decided, at the same time as limiting any subsidy to £60k and the amount be the same as that for Ibn Saud, needed input from the Foreign Office and Curzon wanted Hussein's signature on the peace treaties.

Refusal to sign treaties

[edit]In 1919, King Hussein refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. In August 1920, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, Curzon asked Cairo to procure Hussein's signature to both treaties and agreed to make a payment of £30,000 conditional on signature. Hussein declined and in February 1921, stated that he could not be expected to "affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners."[94]

In July 1921, Lawrence was assigned to the Foreign Office for the purpose of obtaining a treaty arrangement with Hussein as well as the King's signature to Versailles and Sèvres, a £60,000 annual subsidy being proposed; achieving this, which would include the so far denied recognition of the mandates, would constitute the completion of the Sherifian triangle but this attempt also failed.[95] During 1923, the British made one further attempt to settle outstanding issues with Hussein and once again, the attempt foundered, Hussein continued in his refusal to recognize any of the Mandates that he perceived as being his domain. Hussein went to Amman in January 1924 and had further discussions with Samuel and Clayton. In March 1924, following Hussein's self proclamation as Caliph and having briefly considered the possibility of removing the offending article from the treaty, the government suspended any further negotiations.

The British and the pilgrimage

[edit]The importance of Mecca to the Muslim world (at the time, Britain effectively ruled a Muslim empire) and to Britain itself as a potential center of rebellion against the Ottoman led to enhanced attention based on the idea that a successful hajj would not only enhance Hussein's standing but indirectly, that of Britain as well.[96]

1924 Caliphate claim

[edit]On 7 March 1924, four days after the Ottoman Caliphate was abolished, Hussein proclaimed himself Caliph of all Muslims.[97] However, Hussein's reputation in the Muslim world had been damaged by his alliance with Britain, his rebellion against the Ottoman Empire, and the division of the ex-Ottoman Arab region into numerous countries; as a result his proclamation attracted more criticism than support in populous Muslim countries like Egypt and India.[98]

Relations with Nejd

[edit]Nearing the end of 1923, the Hejaz, Iraq and Transjordan all had frontier issues with Najd. The Kuwait conference commenced in November 1923 and continued off and on to May 1924. Hussein initially declined to attend other than under conditions unacceptable to Ibn Saud; the refusal of the latter to send his son, after Hussein had finally agreed to be represented by his own son Zeid, ended the conference.[99]

Abdication

[edit]After local pressure, Hussein abdicated on 4 October 1924, leaving Jeddah for Aqaba on 14 October. Ali took the throne and also abdicated on 19 December 1925, leaving to join Faisal in Iraq, ending Hashemite rule in the Hejaz.[100]

Sharifian family tree

[edit]Relations between family members:[101]

Sharif of Mecca November 1908 – 3 October 1924 King of Hejaz October 1916 – 3 October 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Hejaz 3 October 1924 – 19 December 1925 (Monarchy defeated by Saudi conquest) | Emir (later King) of Jordan 11 April 1921 – 20 July 1951 | King of Syria 8 March 1920 – 24 July 1920 King of Iraq 23 August 1921 – 8 September 1933 | Zeid (pretender to Iraq) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Abd Al-Ilah (Regent of Iraq) | King of Jordan 20 July 1951 – 11 August 1952 | King of Iraq 8 September 1933 – 4 April 1939 | Ra'ad (pretender to Iraq) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Jordan 11 August 1952 – 7 February 1999 | King of Iraq 4 April 1939 – 14 July 1958 (Monarchy overthrown in coup d'état | Zeid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Jordan 7 February 1999 – present | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hussein (Crown Prince of Jordan) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Abdullah's reaction to this is not known, according to author Ian Rutledge[46] while Rudd refers to a conversation between Abdullah and Vickery on 1 March: "...He would certainly like to be the Emir of Iraq if guaranteed British support and aid for at least 20 years. He would not accept a position in any country for which Great Britain had not the mandate..."[47]

- ^ In his Setting the Desert on Fire published 2 years earlier, Barr had in addition described how after being missing for nearly fifteen years, copies of the Arabic versions of the two most significant letters were found in a clear-out of Ronald Storrs's office in Cairo. "This careless translation completely changes the meaning of the reservation, or at any rate makes the meaning exceedingly ambiguous,"the Lord Chancellor admitted, in a secret legal opinion on the strength of the Arab claim circulated to the cabinet on 23 January 1939.[64]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "BBC NEWS – UK – Lawrence's Mid-East map on show". 11 October 2005.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene L. (2016). "The Emergence of the Middle East into the Modern State System". In Fawcett, Louise (ed.). International relations of the Middle east. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-870874-2.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 246.

- ^ Arab Awakening. Taylor & Francis. 19 December 2013. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-317-84769-4.

- ^ William E. Watson (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-275-97470-1.

- ^ Eliezer Tauber (5 March 2014). The Arab Movements in World War I. Routledge. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-135-19978-4.

- ^ Troeller, Gary (23 October 2013). The Birth of Saudi Arabia: Britain and the Rise of the House of Sa'ud. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-16198-9.

- ^ Zamir, Meir (6 December 2006). "Faisal and the Lebanese question, 1918–20". Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (3): 404. doi:10.1080/00263209108700868.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Lieshout, Robert H. (2016). Britain and the Arab Middle East: World War I and its Aftermath. I.B.Tauris. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-78453-583-4.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Elie Kedouri (8 April 2014). In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and its Interpretations 1914–1939. Routledge. pp. 229–. ISBN 978-1-135-30842-1.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 253.

- ^ Ayse Tekdal Fildis. "The Troubles in Syria: Spawned by French Divide and Rule". Middle East Policy Council. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Philips S. Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate; The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–1945 Middle East Studies I. B. Tauris, 1987, p=442

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 269.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 586.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 278.

- ^ a b Friedman 2017, p. 272.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 290.

- ^ Bennett 1995, p. 104.

- ^ One example querying British compliance with the Mandate being Hansard, [1]: HL Deb 15 June 1921 vol 45 cc559-63

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Michael J. Cohen (13 September 2013). Churchill and the Jews, 1900–1948. Taylor & Francis. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-1-135-31913-7.

- ^ Bennett 1995, p. 111.

- ^ Reeva Spector Simon; Michael Menachem Laskier; Sara Reguer (30 April 2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. Columbia University Press. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-0-231-50759-2.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 360.

- ^ Rudd 1993, pp. 305, 309.

- ^ Middle East, HC Deb 14 June 1921 vol 143 cc265-334

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 309.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 312.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 305.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 307.

- ^ Report on Middle East Conference held in Cairo and Jerusalem, March 12th to 30th, 1921, Appendix 19, p. 109-111. British Colonial Office, June 1921 (CO 935/1/1)

- ^ Joab B. Eilon; Yoav Alon (30 March 2007). The Making of Jordan: Tribes, Colonialism and the Modern State. I.B.Tauris. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-84511-138-0.

- ^ Macmunn & Falls 1930, p. 609: "The Arab zone was divided into two, the southern of which became, and remains to-day, the mandated territory of Trans-Jordan, under the rule of Abdulla, Hussein's second son. At Damascus the experiment was tried of a French-protected State under Feisal, but it speedily failed. Feisal was ejected by the French in July 1920, and Zone A linked with the Blue Zone under a common administration."

- ^ Dann, U. (1969). The Beginnings of the Arab Legion. Middle Eastern Studies,5(3), 181-191. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4282290 "...the interregnum between Faysal's departure from Syria and 'Abdallah's installation at 'Amman."

- ^ Norman Bentwich, England in Palestine, p51, "The High Commissioner had ... only been in office a few days when Emir Faisal ... had to flee his kingdom" and "The departure of Faisal and the breaking up of the Emirate of Syria left the territory on the east side of Jordan in a puzzling state of detachment. It was for a time no-man's-land. In the Ottoman regime the territory was attached to the Vilayet of Damascus; under the Military Administration it had been treated a part of the eastern occupied territory which was governed from Damascus; but it was now impossible that that subordination should continue, and its natural attachment was with Palestine. The territory was, indeed, included in the Mandated territory of Palestine, but difficult issues were involved as to application there of the clauses of the Mandate concerning the Jewish National Home. The undertakings given to the Arabs as to the autonomous Arab region included the territory. Lastly, His Majesty's Government were unwilling to embark on any definite commitment, and vetoed any entry into the territory by the troops. The Arabs were therefore left to work out their destiny."

- ^ Pipes, Daniel (26 March 1992). Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-19-536304-3.

- ^ Edward W. Said; Christopher Hitchens (2001). Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question. Verso. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-1-85984-340-6.

- ^ Vatikiotis, P.J. (18 May 2017). Politics and the Military in Jordan: A Study of the Arab Legion, 1921–1957. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-78303-3.

- ^ Gökhan Bacik (2008). Hybrid sovereignty in the Arab Middle East: the cases of Kuwait, Jordan, and Iraq. Macmillan. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-230-60040-9. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Ian Rutledge (1 June 2015). Enemy on the Euphrates: The Battle for Iraq, 1914–1921. Saqi. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-86356-767-4.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 257.

- ^ Charles Tripp (27 May 2002). A History of Iraq. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-52900-6.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 301.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 122.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 312.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 304.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 309.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 0119.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 318.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 316.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 316.

- ^ Barry Rubin; Wolfgang G. Schwanitz (25 February 2014). Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Yale University Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-300-14090-3.

- ^ Younan Labib Rizk (21 August 2009). Britain and Arab Unity: A Documentary History from the Treaty of Versailles to the End of World War II. I.B.Tauris. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-85771-103-8.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 319.

- ^ a b Friedman 2017, p. 297.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 298.

- ^ Barr, James (2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84983-903-7.

- ^ James Barr (7 November 2011). Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence and Britain's Secret War in Arabia, 1916–18. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 250–. ISBN 978-1-4088-2789-5.

- ^ Elie Kedouri (8 April 2014). In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and its Interpretations 1914–1939. Routledge. pp. 237–41. ISBN 978-1-135-30842-1.

- ^ Paris 2004, pp. 257, 268.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 299.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 312.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 121.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 317.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 321.

- ^ a b Allawi 2014, p. 322.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 128.

- ^ Allawi 2014, pp. 322–333.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 277.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 129.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 323.

- ^ Hansard, "PLEDGES TO ARABS.": HC Deb 11 July 1922 vol 156 cc1032–5

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 318.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 130.

- ^ Susan Pedersen (29 April 2015). The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-19-022639-8.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 326.

- ^ Efraim Karsh; Inari Karsh (2001). Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923. Harvard University Press. pp. 286–. ISBN 978-0-674-00541-9.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 307.

- ^ Paris 2004, pp. 129–30.

- ^ "Memorandum Submitted to the Conference of Allied Powers at the House of Commons". Unispal. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 329.

- ^ Efraim Karsh; Inari Karsh (June 2009). Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923. Harvard University Press. pp. 392–. ISBN 978-0-674-03934-6.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 333.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 336.

- ^ Allawi 2014, pp. 336, 379.

- ^ Mousa, Suleiman (1978). "A Matter of Principle: King Hussein of the Hejaz and the Arabs of Palestine". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 9 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000052. S2CID 163677445.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 252.

- ^ John Slight (12 October 2015). The British Empire and the Hajj. Harvard University Press. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-0-674-91582-4.

- ^ Teitelbaum, Joshua (2000). ""Taking Back" the Caliphate: Sharīf Ḥusayn Ibn ʿAlī, Mustafa Kemal and the Ottoman Caliphate". Die Welt des Islams. 40 (3): 412–424. doi:10.1163/1570060001505343. JSTOR 1571258.

- ^ Al-Rasheed, Madawi; Kersten, Carool; Shterin, Marat (12 November 2012). Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-19-025712-5.

- ^ Paris 2004, pp. 335–337.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 344.

- ^ "Welcome to the Office of King Hussein I dedicated to the father of Modern Jordan". The Royal Hashemite Court. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-300-19936-9.

- Bennett, G. (9 August 1995). British Foreign Policy during the Curzon Period, 1919–24. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-37735-6.

- Friedman, Isaiah (8 September 2017). British Pan-Arab Policy, 1915–1922. Taylor & Francis. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-351-53064-4.

- Paris, Timothy J. (23 November 2004). Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule: The Sherifian Solution. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77191-1.

- Rudd, Jeffery A. (1993). Abdallah bin al-Husayn: The Making of an Arab Political Leader, 1908–1921 (PDF) (PhD). SOAS Research Online. pp. 45–46. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Macmunn, G. F.; Falls, C. (1930). Military Operations: Egypt and Palestine, From June 1917 to the End of the War Part II. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. accompanying Map Case (1st ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 656066774.