Royal Cemetery at Ur

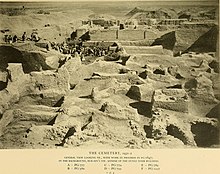

General view of the Royal Cemetery at Ur, during excavations. | |

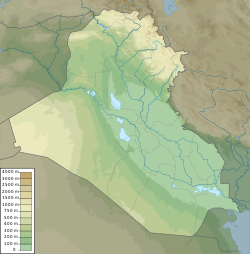

| Location | Tell el-Muqayyar, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 30°57′41″N 46°06′22″E / 30.9615°N 46.1061°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 3800 BC |

| Abandoned | After 500 BC |

| Periods | Ubaid period to Iron Age |

| Cultures | Sumerian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1853–1854, 1922–1934 |

| Archaeologists | John George Taylor, Leonard Woolley |

The Royal Cemetery at Ur is an archaeological site in modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate in southern Iraq. The initial excavations at Ur took place between 1922 and 1934 under the direction of Leonard Woolley in association with the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

Many finds are now in museums, especially the Iraq Museum, Baghdad and the British Museum.

Discovery

[edit]

The process was begun in 1922 by digging trial trenches, in order for the archaeologists to get an idea of the layout of the ancient city that would be documented in drawings by Katharine Woolley. In one trench where initially nothing was discovered, head archaeologist Leonard Woolley decided to dig deeper. There, clay vases, limestone bowls, small bronze objects, and assorted beads were found. Woolley thought that there may have been gold beads and, to entice the workers to turn them in when found, Woolley offered a sum of money—this led to the discovery of the gold beads after the workers repurchased them from the goldsmiths they sold them to.[1]

Dishonesty of the workers was an issue, but not the only in the preliminary digs. The locals hired to help had no previous experience in archaeology, leading Woolley to abandon what they referred to as the "gold trench" for four years, until the workers became better versed in archaeological digs. In addition, archaeology was still in the beginning stages as a field. As a result, gold objects were identified by an expert who dated them incorrectly to the "Late Babylonian" (c. 700 BC), when in fact they dated back to the reign of Sargon I (c. 2300 BC).[2]

The cemetery at Ur included slightly more than 2000 burials. Amongst these burials were sixteen tombs identified by Woolley as "royal" tombs based on their size and structure, variety and richness of grave goods, as well as the existence of artifacts associated with mass ritual.[3]

The site

[edit]The ruins of the ancient city of Ur can be found in the desert of southern Iraq. The city remained abandoned after the Euphrates River changed its course more than two millennia ago. Early archaeologists dug into the surface and recovered graves, some of which had royal names inscribed on them. Woolley began his excavation in 1922 on behalf of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. However, the actual discovery of the cemetery and its royal tombs was four years later after the excavation started. The large cemetery was in operation for at least three centuries during the second half of the third millennium BC. Most of the graves were individual burials that had cut into one another. Male and female corpses were found with their belongings that identified them as either rich or poor.[4]

Woolley initially unearthed 1850 graves but later identified 260 additional ones.[5] Nevertheless, sixteen were unique to him, because they stood out from all the rest in terms of their wealth, the structure of their burial grounds, and rituals. He thought that the stone-built chambers and the immense value of riches belonged to the dead that came from royal lineage. Such cadavers inside their respective stone chambers were the only ones to have abundant provisions in order to meet their needs in the afterlife. Having that said, the subordinates were not treated in the same manner and had nothing of the aforementioned goods. They were treated in the same manner as other provisions and supplies, because the funeral was solely for the principal corpse. When the main body was buried, the rest of the people would have been sacrificed in that person's honor and buried thereafter.[6]

When Woolley found the Great Death Pit (PG 1237), it was in extremely poor condition. What remained of the chamber were a few stones and some gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian beads in fine condition. The Great Death Pit was an open square-shaped space, serving as the graveyard for the bodies of armed men that were laid out inside along with other corpses thought to belong to women or young girls.[7] The introduction of massive death pits at Ur is usually associated to Meskalamdug, one of the kings of Ur that was also known as the paramount ruler of all the Sumerians. He started the practice of such a massive entombment with the sacrifice of soldiers and an entire choir of women to accompany him in the afterlife.[4] It has also been suggested that the Great Death Pit was the tomb of Mesannepada.[8]

Puabi

[edit]

In contrast to the Great Death Pit, one of the royal tombs at Ur survived practically in its entirety, which was most notably due to its treasures left largely unscathed on the body of royal lineage. Such a body belonged to Queen Puabi and was easy to identify due to her jewelry made out of beads of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and agate. Nevertheless, the biggest clues that denoted her title as queen was a cylinder seal with her name on the inscription and her crown, which was made out of layers of gold ornaments shaped in intricate floral patterns. Once more, Woolley uncovered an earth ramp leading down to the death pit of the well-preserved tomb, which was twelve by four meters approximately, and found a menagerie of corpses that ranged from armed men to women wearing headdresses with elaborate details. In his descent toward the pit, he found traces of reed matting, and they covered the artifacts and bodies in order to avoid contact with the soil that had filled the royal grave. Two meters below the level of the pit laid a tomb chamber built of stone that had no doorway in its walls, and its only accessible entrance was through its roof. Once inside, four bodies rested inside the tomb, but the most important one was evidently that of the queen.[9]

Burial practices

[edit]The bodies at the Royal Cemetery underwent certain burial practices. In the tombs, the primary inhumation is placed inside the tomb chamber usually accompanied by attendants. More bodies or victims are also buried, often in separate chambers or, more commonly, in 'death pits' - open, sunken courts.[6] The amount of sacrificed bodies in one tomb can range from as few as six to between seventy and eighty bodies.[6] The attendants are usually lying in neat rows within the death pits or chambers.[3] It is not entirely known if the attendants died placed in that manner or were positioned after death.[3] The principal body was always laid on a mat made of reeds which also lined the floor and walls of the pit where the attendants are located.[6] In some tombs the bodies are arranged in very specific ways. Some tombs were found with male skeletons with helmets and spears positioned in front of the entrance as guards and then contained female attendants inside.[3]

It is not known for sure who the primary inhumations were but it is generally assumed that they are royalty. The occupants are possibly related either by blood or marriage.[5] Additionally, there is little textual evidence available to explain the tombs at the cemetery and the practices of the people but it is thought that the burials of the royalty consisted of multi-day ceremonies.[6] Some of the bodies have evidence of heating or smoking which could have been an attempt at preserving the bodies to last through the ceremony.[5] Additionally mercury has been found on some skulls which could also indicate an attempt at preservation.[5] Music, wailing, and feasting took place in addition to the burial with the possibility of the attendants joining in.[5] In the first part of the ceremony the body was laid in the tomb, along with the offerings, and then sealed with brick and stone.[6] In the next part of the ceremony the death pits were filled with guards, attendants, musicians, and animals, such as oxen or donkeys.[6]

How the attendants ended up buried with the royalty is somewhat unknown. All of the bodies are arranged in an ordered fashion and appear peaceful.[3] The elaborate headdresses worn by women are undisturbed which supports the assumption they were lying or sitting down when they died.[6] Woolley thought initially that the attendants were human sacrifices and were killed to show the kings' power and put on a public show.[5] Later he speculated that the attendants voluntarily consumed poison to continue serving their head in death.[5] Each attendant was found with a small cup nearby which they could drink the poison from.[6] The poison could have been a sedative with the cause of death being suffocation from having the chamber sealed.[3] Some research has found that some of the skulls had received blunt force trauma indicating that, rather than voluntarily serving their superiors in death, they were forcibly killed.[5]

Grave goods

[edit]

The cemetery at Ur contained more than 2000 burials alongside a corresponding wealth of objects. Many items come from the handful of royal burials. Many of these grave goods were likely imported from various surrounding regions including Afghanistan, Egypt, Ethiopia and the Indus valley. Objects of significance varied from cylinder seals, jewelry and metalwork, to pottery, musical instruments, and more.

Cylinder seals

[edit]Cylinder seals found amongst the grave goods in the cemetery at Ur were often inscribed with the names of the deceased.[3] Excavators retrieved three cylinder seals near queen Puabi's remains, one with her name written in cuneiform.[10]

Jewelry and metalwork

[edit]The various female personages and attendants buried at the cemetery of Ur were adorned with jewelry made from gold, silver, lapis lazuli and carnelian including a variety of necklaces, earrings, headdresses, and hair rings. The presence of carnelian beads amongst the grave goods at the cemetery indicated trade with the Indus Valley. Hair ornaments included hair combs with floral elements made of gold, lapis, shell, and pink limestone. In addition, hair ribbons of gold and silver and inlaid combs with rosettes were also found amongst the human remains at Ur.[3]

Many of the jewels contained some sort of botanical reference. Amongst them are vegetal wreaths fashioned with gold leaves. Notably, Puabi's headdress consists of four botanical wreaths including rosettes or stars and leaves.[11]

Other precious metals were found in the form of helmets, daggers, and various vessels in copper, silver, and gold. A gold helmet, whose ownership is attributed to Meskalamdug was found in a grave that Woolley believed to be an elite, but not necessarily a king.[13] The helmet was made from a single piece of gold and fashioned to resemble a wig.[14]

The presence of fully developed casting practices is assumed from the discovery of another weapon made from electrum. At the same time, another weapon, referred to as the "Dagger of Ur," was, according to Woolley, the first significant grave good discovered at Ur. The sheath and blade are both made from gold with a handle of lapis lazuli with gold decoration. Other examples of metal work include a variety of golden goblets and vessels made with handles of twisted wire. Some of these vessels included relief decoration or patterning. Hammered work in various metals was also discovered. This included a shield ornament containing an Assyrian style subject of lions and men being trampled. Other objects included a silver fluted bowl with engravings and a silver model of a sea faring vessel.[14]

Pottery

[edit]The pottery types at Ur included mostly jar forms and bowls with limited variety in style. Conical bowls, as recorded by the excavators, fall into two categorical types based on their rim diameters. Woolley identified 24 different pottery types at the Royal Cemetery based on the excavation of 238 graves. In order to date the pottery and burials at Ur, some scholars have looked to the pottery to compare to similar types from other sites in Mesopotamia and then checked using cylinder seals.[15]

Musical instruments

[edit]Amongst the finds at Ur were the remains of highly decorated musical instruments. Several lyres were discovered in the main pit associated with four women.[3] Most of these instruments were wooden with silver overlay alongside other details. One lyre's sound box was made from silver with blue and white mosaic detail and engraved shell with pictorial engravings on the front created using a similar technique to niello work. This particular lyre also included a silver cast cow's head and silver tuning rods. Another lyre was shaped like a seafaring vessel supporting the statue of a stag. Yet another lyre incorporated various materials including wood, shell, lapis lazuli, red stone, silver and gold. The lyres found at Ur often included the representation of animals including a cow, stag, bearded bull, and a calf. Of particular note is the Bull-headed lyre from PG 789, also referred to as the "King's Grave". Woolley theorized that each animal might have corresponded to the tone of the instrument itself.[14]

Ram in a Thicket

[edit]

The discovery of two goat statues in PG 1237 are just two examples of polychrome sculpture at Ur. These objects, referred to as "rams in the thicket" by Woolley, were made of wood and covered in gold, silver, shell and lapis lazuli.[3] The Ram in a Thicket uses gold for the tree, legs, and face of the goat, silver for the belly and parts of the base alongside pink and white mosaics. The back of the animal is constructed using shell attached with bitumen. Other details such as the eyes, horns, and beard are fashioned from lapis lazuli.[14]

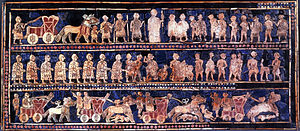

The Standard of Ur

[edit]

Discovered in PG 779 was a, as yet, unidentified object referred to as the Standard of Ur.[3] The Standard of Ur is a trapezoidal wooden box incorporating lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone into the depiction of various figures on its surface. Its function is debated, although Woolley believed it to be a military standard, explaining this object's current name. On each side of the standard, the pictorial elements are considered part of a narrative sequence divided formally into 3 registers with all figures on a common ground. The standard uses hierarchy of scale to identify important figures in the compositions. Read from left to right, bottom to top on one side of the standard, starting with the lowest registers, there are men carrying various goods or leading animals and fish towards the top register where larger seated figures take part in a feast accompanied by musicians and attendants. The other side depicts a more militaristic subject where men in horse-drawn chariots trample over prostrate bodies and soldiers and prisoners process up towards the top frieze where the central personage is designated by his large scale, punctuating the border of the upper most frieze.[10]

Present day

[edit]New theories

[edit]Analyses of the findings of Sir Leonard Woolley have led to new theories concerning the royal tombs.

In 1998, Paul Zimmerman wrote a master's thesis while at the University of Pennsylvania on the Royal Cemetery at Ur. Graves PG789 and PG800, the king and queen's graves, according to Woolley, were complete burials with attendants and worldly possessions. Zimmerman analyzed the layout and formulated the hypothesis that the two tombs were in fact three. Pit PG800 had two rooms that were on two different levels, something that Zimmerman found inconsistent with grave PG789 (the rooms were connected). In addition, Woolley claimed that Puabi's grave was built after the king's in order to be close to him. Zimmerman posits that, because Puabi's grave was 40 cm lower than that of the king's, her grave was actually built first. With these in mind, Zimmerman claimed that the death pit assigned to Queen Puabi was actually a death pit from a different grave that is unknown.[16]

State of the royal tombs

[edit]

Looting of archaeological sites was a common occurrence brought under control during the reign of Saddam Hussein, whose government declared the act a capital offense. Due to the Iraq War, however, looting has occurred more frequently. Entire archaeological sites have been destroyed, with as many as tens of thousands of holes dug by looters.[17]

The "Royal Cemetery At Ur", however, has remained largely preserved. The site was located in the boundaries of the Tallil Air Base, controlled by allied forces. It was damaged during the first Gulf War, when the air base was bombed. As a result, in 2008, a team of scholars, including Elizabeth Stone of Stony Brook University, found that the walls of the royal tombs were beginning to collapse. Deterioration was also recorded in the team's findings, due to the occupation of the military.

Neglect, however, was cited as most harmful to the site. Stone stated that for 30 years the "Iraq Department of Antiquities" lacked the resources to properly inspect and conserve the site, along with others that the team examined. As a result, sites like the Royal Cemetery at Ur have begun to erode.

In May 2009, "Iraq's State Board of Antiquities" regained control of the site, helping with the conservation of the ancient site.[18]

Graves

[edit]A vast number of individual graves, and a few royal graves have been identified at the Royal Cemetery of Ur. The attribution of the royal graves is generally tentative, but some efforts have been made to match them with royal figures otherwise known through inscriptions or regnal lists such as the Sumerian King List.[19] Julian Reade has tentatively attributed the main tombs to the following rulers:[19][20]

| Main tombs at the Royal Cemetery of Ur | ||

| PG 1236[21] | A-Imdugud, king. The oldest and most monumental tomb at the cemetery.[19] |  |

| PG 779 | Ur-Pabilsag, king, son of A-Imdugud.[19] | |

| PG 777[22] | Tomb of a queen, wife of Ur-Pabilsag.[19] | |

| PG 755 | Tomb of king Meskalamdug.[23] Possibly a prince of the same name, for example a son of Meskalamdug and queen Nibanda.[19][24][25] | |

| PG 1054[26] | Tomb of Nibanda, queen of Meskalamdug.[19] | |

| PG 1130 | Widow of the prince in tomb PG 755.[19] | |

| PG 789 | Tomb of King Meskalamdug, son of Ur-Pabilsag.[19] | |

| PG 800 | Tomb of Puabi, second wife of Meskalamdug, identified as a queen; possible later ruler in her own right.[19] | |

| PG 1050 | Tomb of Ashusikildingir, wife of Meskalamdug.[19] | |

| PG 1332 | Tomb of Akalamdug, king, son of Meskalamdug.[19] | |

| PG 337 | Tomb of a queen, second wife of Akalamdug.[19] | |

| PG 1232/1237 | Tomb of Mesannepada, son of Meskalamdug.[19] | |

| PG 55 | Tomb of a queen, wife of A'anepada.[19] | |

| PG 580 | Tomb of A'anepada, king, son of Mesannepada.[19] | |

| PG 1157[27] | Tomb of Meskiagnuma, king, son of Mesannepada.[19] | |

PG 1236

[edit]Tomb PG 1236, a twin tomb in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, is the largest and probably the earliest tomb structure at the cemetery, dated to circa 2600 BCE.[19] It has been tentatively attributed to an early king of the First Dynasty of Ur named A-Imdugud (𒀀𒀭𒅎𒂂 ADIM.DUGUDMUŠEN, named after God Imdugud, also read Aja-Anzu),[28] whose inscribed seal was found in the tomb.[19]

Several artefacts are known from tomb PG 1236.[29][30] Two inscribed seals were found, one is a banquet scene with an inscription Gan-Ekiga(k), and another with the depiction of a nude hero fighting lions and a war scene reminiscent of the Standard of Ur, with the name Aja-Anzu, also read A-Imdugud.[28] This seals is very similar to the seal of Mesannepada.[28] Gold leaves with embossed designs, as well as a reconstituted gold scepter, have also been found in the tomb,[31] as well as a royal scepter.[31]

-

Scepter, tomb PG 1236.[31]

-

Plan of tomb PG 1236, with three chambers, thought to belong to A-Imdugud. Royal Cemetery of Ur.

-

Tomb PG 1236, at the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Doorway, and domed tomb chambers seen from above.

-

Seal from PG 1236 with inscription "Aja-Anzu", also read "A-Imdugud". Upper register: a nude hero fighting lions. Lower register: chariotter trampling an enemy, and foot soldiers escorting a naked prisoner.[28]

-

Banquet scene with an inscription Gan-Ekiga(k), PG 1236.[28]

-

Gold foil, tomb PG 1236

-

Design embossed on the gold foil, tomb PG 1236, thought to belong to A-Imdugud, Royal Cemetery of Ur.[31]

PG 779

[edit]PG 779 is an early monumental grave, which has been associated with king Ur-Pabilsag (𒌨𒀭𒉺𒉋𒊕, ur-dpa-bil2-sag) an early ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur in the 26th century BCE. He does not appear in the Sumerian King List, but is known from an inscription fragment found in Ur, bearing the title "Ur-Pabilsag, king of Ur".[32][33] It has been suggested that his tomb was grave PG 779.[34][35] He may have died around 2550 BCE.[36]

The tomb of Ur-Pabilsag (Grave PG 779) is generally considered as the second oldest at the site, and probably contemporary with grave PG 777, thought to be the tomb of his queen.[19] Meskalamdug (grave PG 755, or possibly PG 789) was his son.[37]

Several artefacts are known from tomb PG 779 at the Royal Cemetery at Ur, such as the famous Standard of Ur, and decorated shell plaques.[38][39]

-

Tomb of Ur-Pabilsag in the center (PG 779, marked "A"), with the tomb of Meskalamdug on the left (PG 755, marked "B"), next to the royal tomb of the queen of Ur-Pabilsag (PG 777, marked "C").

-

Plan of grave PG 779. The Standard of Ur was located in "S"

-

Grave PG 779, the tomb of Ur-Pabilsag.

-

The Standard of Ur, from tomb PG 779.

-

Shell inlay from tomb PG 779

-

King at war, with soldiers, from the Standard of Ur.

PG 755: "Prince Meskalamdug"

[edit]PG 755 is a small individual grave without attendants, generally attributed to king Meskalamdug (𒈩𒌦𒄭, MES-KALAM-DUG[40] "hero of the good land")[41] Alternatively, since the tomb lacks of royal characteristics, it has been suggested that it may belong to a prince, for example the son of Meskalamdug.[19]

The tomb contained numerous gold artifacts including a golden helmet with an inscription of the king's name.[42] By observing the contents of this royal grave, it is made clear that this ancient civilization was quite wealthy. Meskalamdug was probably the father of king Mesannepada of Ur, who appears in the king list and in many other inscriptions.[42]

-

Grave of Meskalamdug (PG 755, "A")

-

Grave of Meskalamdug (PG 755, marked "B" on the left), next to royal tomb of Ur-Pabilsag (PG 779, marked "A" in the center) and tomb of Ur-Pabilsag's queen on the right (PG 777, "C")

-

A gold dagger and a dagger with a gold-plated handle, grave PG 755, Ur excavations (1900).

-

Alabaster vases and helmet from the grave of Meskalamdug, grave PG 755

-

Golden bowls found in the tomb of Meskalamdug (grave PG 755), with vertical inscription of his name 𒈩𒌦𒄭, "Meskalamdug".

-

Golden bowl from the grave of Meskalamdug (PG 755, Ur)

-

Gold monkey of Meskalamdug (grave PG 755 at Ur)

-

Silver ewer and copper paten from the tomb of Meskalamdug.

Tomb PG 1054: "Queen of Meskalamdug"

[edit]This grave exhibits many characteristics of a royal burial.[43] It is thought to belong to Nibanda, Queen of Meskalamdug.

-

The grave

-

Seal of King Meskalamdug

Tomb PG 789: "the King's grave"

[edit]

According to Julian Reade tomb PG 755 was the tomb of a "Prince Meskalamdug", but the actual tomb of King Meskalamdug, known from seal U 11751, is more likely to be royal tomb PG 789.[19] This tomb has been called "the King's grave", where the remains of numerous royal attendants and many beautiful objects were recovered, and is located right next to the tomb of Queen Puabi, thought to be the second wife of King Meskalamdug.[19][44]

-

Funeral disposition in the great death pit, PG 789. The King's tomb would be the dome in the back (reconstitution).

-

Plan of tomb PG 789.

-

Bull head in a lyre.

-

Bull-headed lyre recovered from the royal cemetery of Ur Iraq 2550-2450 BCE

-

Nacre plate on lyre, with anthropomorphic animals, PG 789.

-

Master of animals motif in a panel of the soundboard of the Ur harp

-

Plate from PG 789.

-

Weapons from tomb PG 789.

-

Silver model of a boat, tomb PG 789, 2600-2500 BCE

Tomb PG 800: "Queen Puabi"

[edit]This is the tomb of Queen Puabi, located next to tomb PG 789. She is thought to be the second wife of Meskalamdug.[19]

-

Tomb PG 800

-

Reconstructed Sumerian headgear necklaces found in the tomb of Puabi, housed at the British Museum

-

Queen's Lyre, one of the Lyres of Ur, Ur Royal Cemetery.

-

Inlay with two standing goats, Ur, Tomb PG 800

Tomb 1237: "the Great Death Pit"

[edit]According to Julian Reade, tomb PG 1237, nicknamed "the Death-Pit", may possibly be attributed to king Mesannepada.[48]

-

Disposition of royal attendants in tomb PG 1237

-

Ram in a Thicket in PG 1237

-

Silver lyre, PG 1237

-

The golden bull's head from the lyre, PG 1237

-

Woman's head with jewellery, preserved as excavated, British Museum

Tomb PG 580

[edit]Possible tomb of A'anepada, king, son of Mesannepada.[19]

-

Gold items PG 580.

-

Dagger

-

Copper alloy axe

-

Copper Alloy Chisel, Harpoons, Lance and Spear Heads.

-

Jewellery PG 580

-

Jewellery PG 580

Gallery

[edit]-

The Ur Queen's Lyre from Wooley's published record

-

Headdress decorated with golden leaves; 2600-2400 BC; gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian; length: 38.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A tomb as restored today.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Woolley, Leonard C. (1954). Excavations at Ur. London: Ernest Benn Limited. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Woolley, Leonard C. (1954). Excavations at Ur. London: Ernest Benn Limited. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Irving, Alexandra and Janet Ambers. "Hidden Treasure from the Royal Cemetery at Ur: Technology Sheds New Light on the Ancient Near East." Near Eastern Archaeology 65, no. 3 (September, 2002): 206-213.

- ^ a b Reade, Julian. "The Royal Tombs of Ur." In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, edited by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels New York and New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of New York and Yale University Press, 2003. 93-94,96.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baadsgaard, Aubrey, Monge, Janet, Cox, Samantha, and Zettler, Richard L. "Human Sacrifice and Intentional Corpse Preservation in the Royal Cemetery of Ur." Antiquity 85, no. 327 (2011): 27-42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Woolley, Leonard. Ur Excavations. vol. 2. The Royal Cemetery. (London: Publications of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania to Mesopotamia, 1934). 33, 37-38.

- ^ Reade, Julian. "The Great Death Pit at Ur." In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, edited by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (New York and New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of New York and Yale University Press, 2003). 120.

- ^ Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Collins, Paul. "The Tomb of Puabi." In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, edited by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels New York and New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of New York and Yale University Press, 2003. 108, 111.

- ^ a b Kliener, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 14th Edition.

- ^ Miller, Naomi F. "Plant Forms in Jewelry from the Royal Cemetery at Ur." Iraq 62 (2000): 149-155.

- ^ British Museum notice: "Gold and carnelians beads. The two beads etched with patterns in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley. They were made by a technique developed by the Harappan civilization" Photograph and notice for the necklace

- ^ Millerman, Alison. "Interpreting the Royal Cemetery of Ur Metalwork: A Contemporary Perspective from the Archives of James R. Ogden." Iraq 70 (2008): 1-12.

- ^ a b c d Woolley, Leonard C. "Excavations at Ur." Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 82, no. 4227 (November 24, 1933): 46-59.

- ^ Pollock, Susan. "Chronology of the Royal Cemetery of Ur." Iraq 47 (1985): 129-158

- ^ "Challenging Theories". Iraq's Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur's Royal Cemetery. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ "The Current Story". Iraq's Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur's Royal Cemetery. Penn Museum. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Owen, James. "Neglect, Not Looting, Threatens Iraq Sites, Study Says". National Geographic. National Geographic News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Reade, Julian (2001). "Assyrian King-Lists, the Royal Tombs of Ur, and Indus Origins". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 60 (1): 18. doi:10.1086/468883. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 545577. S2CID 161480780.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 111.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. pp. 53–.

- ^ "Woolley assumed that there were two people called Meskalamdug, but it is more likely that we are dealing with one individual, whose grave furniture reflected his importance in temple hierarchy, and who at a later stage of his life assumed the title lugal as inscribed on the seal found in PG1054." in Ur. Iraqi Cultural Centre. 1981. p. 37.

- ^ Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. 1998. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3.

- ^ Tinney, Steve; Sonik, Karen (2019). Journey to the City: A Companion to the Middle East Galleries at the Penn Museum. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-931707-17-6.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 97.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b c d e Orientalia: Vol. 73. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 182.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1934). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. Plaques 116, 117.

- ^ Hamblin, William James. Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history, p. 49. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- ^ a b c d Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. [n.p.] Pub. for the Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. pp. 111–113.

- ^ Inscription "1. {d}LAK566 2. ur-{d}pa-bil2-sag3. lugal uri2#[{ki}-ma]" on fragment BM 124348 in "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ For a photograph: Benati, Giacomo. "The "Archaic I" Phase of the Ziqqurat Terrace at Ur: A Contextual Re-assessment". Mesopotamia Xlviii (2013): 197-220: 216, Cat. 33.

- ^ Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Martos, Manuel Molina (2015). Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie. De Gryuter. p. 437.

- ^ Hamblin, William James. Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history, p. 49. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- ^ Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1934). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. Plaques 116, 117.

- ^ Hamblin, William James. Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history, p. 49. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1934). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. Plates 163, 191.

- ^ Excavations At Ur. Routledge. 2013. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-136-21137-9.

- ^ a b "Behind the deceased's head was agold helmet. He held in his hands a gold bowl inscribed with the name Meskalamdug. In the coffin, for example, were gold and silver lamps, a second gold bowl inscribed with the name Meskalamdug, and electrum ax heads. On the northeast side opposite the upper part of the body was a substantial collection of jewelry" in Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780924171543.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. pp. 97–102.

- ^ Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 63.

- ^ British Museum notice WA 121544

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 9781136219115.

- ^ Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 9780924171550.

- ^ Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Found loose in soil at the cemetery Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 525.

![Scepter, tomb PG 1236.[31]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Artifacts_from_PG_1236_%28scepter%29.jpg/700px-Artifacts_from_PG_1236_%28scepter%29.jpg)

![Seal from PG 1236 with inscription "Aja-Anzu", also read "A-Imdugud". Upper register: a nude hero fighting lions. Lower register: chariotter trampling an enemy, and foot soldiers escorting a naked prisoner.[28]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Seal_from_PG_1236_with_inscription_Aja-Anzu%2C_also_read_A-Imdugud.jpg/120px-Seal_from_PG_1236_with_inscription_Aja-Anzu%2C_also_read_A-Imdugud.jpg)

![Banquet scene with an inscription Gan-Ekiga(k), PG 1236.[28]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Banquet_scene_with_an_inscription_Gan-Ekiga%28k%29_PG_1236.jpg/120px-Banquet_scene_with_an_inscription_Gan-Ekiga%28k%29_PG_1236.jpg)

![Design embossed on the gold foil, tomb PG 1236, thought to belong to A-Imdugud, Royal Cemetery of Ur.[31]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Design_embossed_on_gold_leaf%2C_PG_1236%2C_Royal_Cemetery_of_Ur.jpg/120px-Design_embossed_on_gold_leaf%2C_PG_1236%2C_Royal_Cemetery_of_Ur.jpg)

![Cylinder seal of Queen Puabi, found in her tomb. Inscription 𒅤𒀀𒉿 𒊩𒌆Pu-A-Bi-Nin "Queen Puabi".[45][46][47]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Flickr_-_Nic%27s_events_-_British_Museum_with_Cory_and_Mary%2C_6_Sep_2007_-_185.jpg/120px-Flickr_-_Nic%27s_events_-_British_Museum_with_Cory_and_Mary%2C_6_Sep_2007_-_185.jpg)

![Plaque with a libation scene, found in loose ground around the graves. 2550-2250 BCE, Royal Cemetery at Ur.[49][50]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Plaque_with_libation_scene_BM_120850.jpg/147px-Plaque_with_libation_scene_BM_120850.jpg)