Relationship between Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2020) |

The relationship between Ramakrishna and Vivekananda began in November 1881, when they met at the house of Surendra Nath Mitra. Ramakrishna asked Narendranath (the pre-monastic name of Vivekananda) to sing. Impressed by his singing talent, he invited him to Dakshineswar. Narendra accepted the invitation, and the meeting proved to be a turning point in the life of Narendranath. Initially Narendra did not accept Ramakrishna as his master and found him to be a "mono maniac", but eventually he became one of the closest people in his life. Ramakrishna reportedly shaped the personality of Narendranath and prepared him to dedicate his life to serve humanity. After the death of Ramakrishna, Narendra and his other monastic disciples established their first monastery at Baranagar.

The message of Advaita Vedanta philosophy, the Hinduism tenet, inspired by Ramakrishna, the nineteenth century doyen of revival of Hinduism, was ably and convincingly transmitted by Vivekananda, his illustrious disciple [a] first at the Parliament of the World's Religions held from 11 September 1893 at Chicago and thus began the impressive propagation of the Ramakrishna movement throughout the United States. (Also included in this movement was a message on the four yogas [1]). The two men thereupon launched the Ramakrishna Mission and established the Ramakrishna Math to perpetuate this message and over the years the two organizations have worked in tandem to promote what is popularly called the Ramakrishna Order and this legacy has been perpetuated not only to the western world but to the masses in India to this day. Vivekananda, who was an unknown monk in the United States as of 11 September 1893, before the start of the Parliament, became a celebrity overnight.[2]

After lecturing at the Parliament, Vivekananda travelled between 1893—1897 and 1899–1902 in America and England, conducting lectures and classes. Vivekananda delivered two lectures in New York and England in 1901 on Ramakrishna, which were later compiled into a book — My Master. Vivekananda said — "All that I am, all that the world itself will some day be, is owing to my Master, Shri Ramakrishna."

Background

[edit]Ramakrishna's background

[edit]Ramakrishna was born to a Brahmin family in a small rural village in Bengal. His speech was in a rustic dialect. Right from his childhood, he showed inclinations of paranormal behavior. At the age of 16, he came to join his older brother at Dakshineswar in a new temple where his brother was working as a priest. In 1856, after his brother's death, Ramakrishna succeeded him as a priest of the Dakshineswar Kali Temple,[3] but Ramakrishna did not concentrate on formal worships. He was in pursuit of the highest spiritual knowledge. He conducted religious experimentation, learned about different shashtras from Bhairavi Brahmani, Tota Puri, and others;[4] his spiritual education in Advaita Vedanta is largely attributed to Tota Puri who was the resident monk at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple in 1865.[1] It is believed he achieved the highest spiritual knowledge.[4][5]

Ramakrishna attained spiritual excellence and was fully enlightened about a few truths, which greatly influenced his knowledge of social complexities of life. He had put to practice the tenets of religions such as Hinduism in all its ramifications, Islam and Christianity which made him comment: "I have found it is the same God toward whom all are directing their steps, though along different paths."[6]

Vivekananda's background

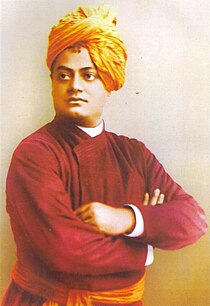

[edit]Vivekananda was born Narendranath Datta on 12 January 1863 in Calcutta into an aristocratic Bengali kayastha family. In his early youth, Narendra joined a Freemasons' lodge and a breakaway faction of the Brahmo Samaj led by Keshub Chandra Sen and Debendranath Tagore. Narendra's initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo concepts, which included belief in a formless God and the deprecation of idolatry.[7][8][9]

Meeting at Surendra Nath Mitra's house

[edit]Surendra Nath Mitra was a noted householder devotee of Ramakrishna, who used to visit Mitra's house in Calcutta to deliver spiritual lectures. It was in Mitra's house where Ramakrishna met Narendranath for the first time in a spiritual festival.[10][11][12] In this festival as the appointed singer could not attend for some reason, young Narendranath, who was a talented singer, was requested to sing songs. Narendra sang few devotional songs and Ramakrishna was impressed by his singing talent. He invited Narendra to come to Dakshineswar and meet him. Though it was their first meeting, neither Ramakrishna nor Narendra counted this as their first meeting.[13][14]

Marriage proposal for Narendra, Rama Chandra Datta's encouragement and Hastie's suggestion

[edit]Narendra's father, Vishwanath Datta, wanted his son to get married and started making arrangements.[10] Narendra was reluctant to marry and was attempting to quench his religious and spiritual thirst.[15] Ram Chandra Datta, the maternal uncle of Bhuvaneswari Devi (Narendra's mother),[16] also asked him to marry, but, Narendra refused.[17] When Ram Chandra learned about Narendra's spiritual thirst, he told him to go to Dakshineswar and meet Ramakrishna. Ram Chandra told Narendra,

If you really want to know the truth, why are you roaming about with Brahmo Samaj? You won't get success in your endeavours here, go to Ramakrishna Paramhansa at Dakshineswar.[12][17][18]

Though suggested by Rama Chandra, Narendra did not find time to go to Dakshineswar and forgot the proposal due to his upcoming F.A. exam pressure.[17] Narendra's next introduction to Ramakrishna occurred in a literature class in General Assembly's Institution when Professor William Hastie was lecturing on William Wordsworth's poem, The Excursion. During the lecture, Wordsworth's use of the word "trance" was explained to mean the experience and feeling of the poet. But Narendra and other students failed to understand. Narendra then asked Professor Hastie to elucidate. Professor Hastie explained its meaning and suggested Narendra goes to Dakshineswar to meet Ramakrishna, a person who experienced "trance".[18][19][20]

Initial meetings

[edit]First meeting at Dakshineswar

[edit]Following the suggestions of Ram Chandra and Professor Hastie, Narendra went to Dakshineswar to meet Ramakrishna.[11] Later, Ramakrishna recalled the day when Narendra first visited Dakshineswar. He said—[21]

Narendra entered the room through the western door facing the Ganges. I noticed that he had no concern about his physical appearance. His hair and clothes were not tidy; like others he had no attachments for external objects. His eyes showed that a greater part of his mind was turned inward all the time. When I observed these, I wondered, is it possible that such a great aspirant could live in Calcutta, the home of the worldly-minded?

Ramakrishna warmly welcomed Narendra and asked him to sit on a mat spread on the floor. Then Ramakrishna asked him to sing a song.[21] Narendra gave his assent and started singing a devotional song—[11]

Let us go back once more,

O mind, to our proper home!

Here in this foreign land of earth Why should we wander aimlessly in stranger's guise?

These living beings round about,

And the five elements,

Are strangers to you, all of them; none are your own.

Why do you so forget yourself,

In love with strangers, foolish mind?

Why do you so forget your own?

When Narendra finished singing, Ramakrishna suddenly became emotional, grasped Narendra's hands and took him into the northern porch of the Kali temple and with tears in his eyes said to him —[11]

Ah! you have come so late. How unkind of you to keep me waiting so long! My ears are almost seared listening to the cheap talk of worldly people. Oh, how I have been yearning to unburden my mind to one who will understand my thought! Then with folded hands he said: 'Lord! I know you are the ancient sage Nara — the Incarnation of Narayana — born on earth to remove the miseries of mankind.

Then Ramakrishna and Narendra returned to their room and started talking. Narendra asked Ramakrishna if he had seen or experienced God.[15] Narendra asked the same question to Debendranath Tagore as well,[22] who skipped the question and praised Narendra's inquisitiveness. But, this time when Narendra asked Ramakrishna the same question, the latter immediately replied in the positive.[13] Without any hesitation, he said: [23]

Yes, I have seen God. I see Him as I see you here, only more clearly. God can be seen. One can talk to him. But who cares for God? People shed torrents of tears for their wives, children, wealth, and property, but who weeps for the vision of God? If one cries sincerely for God, one can surely see Him.

Vivekananda was so much impressed with this meeting that he started visiting Ramakrishna daily when he felt: "Religion could be given. One touch, one glance, can change a whole life".[6]

Narendra felt amazed, as this was the first time he was meeting someone who could say that he had met or experienced God. He also understood those were not mere words, but words uttered from deep inner experiences. He left Dakshineswar and came back to Calcutta in a highly puzzled and bewildered state of mind.[23]

Second meeting at Dakshineswar

[edit]The first meeting with Ramakrishna so much puzzled the young mind of Narendra that he was feeling anxious to meet Ramakrishna again. He finally went to meet him for the second time on a weekday.[13] During the second meeting, he had another strange experience. When he was talking to Ramakrishna, Ramakrishna suddenly placed his right foot on Narendra's chest and Narendra started feeling unconscious, he felt as if everything around him, the rooms, the walls, the temple garden were vanishing away. Narendra got scared and cried out "What are you doing to me? I have my parents, brothers, and sisters at home." Ramakrishna laughed and moved his foot from his body. He restored his consciousness and said, "All right, everything will happen in due time."[23]

Narendra became even more puzzled and felt that Ramakrishna had hypnotized him. He also felt disgusted as he apparently could not resist Ramakrishna from influencing him.[24]

Third meeting at Dakshineswar

[edit]Narendra went to meet Ramakrishna for the third time. This time he was very scared after his last experience. Ramakrishna welcomed Narendra and started talking with him. Narendra was trying to stay alert and not to be hypnotized once again by Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna took him to the adjacent garden and touched him. Narendra failed to resist Ramakrishna's exalted spiritual touch and became unconscious. Ramakrishna later said, after making Narendra unconscious, he asked him many questions such as his previous works, his future aims etc. After receiving answers to his questions, Ramakrishna felt assured, and later he told other disciples that he was confident that Narendra had attained "perfection" in his previous birth.[25][26]

Narendra as an apprentice of Ramakrishna (1882–1886)

[edit]The meetings with Ramakrishna proved to be a turning point in Narendra's life.[27] He started visiting Dakshineswar regularly. Swami Nikhilananda has written—[25]

The meeting of Narendra and Sri Ramakrishna was an important event in the lives of both. A storm had been raging in Narendra's soul when he came to Sri Ramakrishna, who himself had passed through a similar struggle but was now firmly anchored in peace as a result of his intimate communion with the Godhead and his realization of Brahman as the immutable essence of all things.

Narendra was attracted by Ramakrishna's personality, but he initially could not recognize Ramakrishna. After his second day's experience considered him as a "Monomaniac".[28][29] His thoughts had been shaped by the teachings of Brahmo Samaj, which were against "idol worship" and he was an atheist in real life.[30]

Initial reaction

[edit]At first, Narendra would not accept Ramakrishna as his teacher. He tested Ramakrishna in various ways and asked him many critical questions.[31][32][32] Ramakrishna also encouraged Narendranath and told him "Test me as the moneychangers test their coins. You must not believe me without testing me thoroughly."[33] Narendra learned Ramakrishna considered "money" as a hindrance on the path of spirituality and could not tolerate the touch of silver coins (i.e. money). To test this, one day when Ramakrishna was not in his room, Narendra put a silver coin under the mattress of his bed. Ramakrishna entered the room without knowing of Narendra's act, then sat on his bed. But immediately he jumped up in pain and asked someone to check his bed. The bed was searched, and the coin was found.[34][35]

Narendra did not accept or worship Kali, the goddess Ramakrishna used to worship. Ramakrishna asked him— "Why do you come here, if you do not accept Kali, my Mother?" Narendra replied, "Simply because I come to see you. I come to you because I love you."[36]

Accepting Ramakrishna as spiritual teacher

[edit]After many such tests, Narendra started accepting Ramakrishna as his spiritual teacher. He remained with Ramakrishna till Ramakrishna's death in 1886. In the five years since 1882, he closely observed Ramakrishna and took spiritual teachings from him.[32]

Ramakrishna found Narendra a Dhyana-siddha (expert in meditation). Narendra, as an apprentice of Ramakrishna, took meditation lessons from him, which made his expertise on meditation more firm.[37] Narendra was desirous to experience Nirvikalpa Samadhi (the highest stage of meditation) and requested Ramakrishna to help him to attain that state. But, Ramakrishna wanted to prepare young Narendra and devote him for the service of mankind and told him that wishing to remain absorbed in Samadhi was a small-minded desire.[38][39]

Ramakrishna loved Narendra as an embodiment of God (Narayana).[32][40] He himself explained the reason to Narendra— "Mother says that I love you because I see the Lord in you.[41][42] The day I shall not see Him in you, I shall not be able to bear even the sight of you. He compared Narendra with "a thousand-petalled lotus", "a jar of water", "Halderpukur", "a red-eyed carp" and "a very big receptacle".[b][43] He asked others not to attempt to assess or judge Narendra as he felt people would never be able to understand or judge him.[32] He also compared Narendra to a big pigeon.[43][44][45]

Narendra's absence started making Ramakrishna very anxious. Once, Narendra did not come to Dakshineswar for several weeks. Then, Ramakrishna himself went to a Brahmo Samaj meeting to meet him. On another instance he went to the house of Narendra in North Calcutta to meet him.[41][46] On this occasion the immense effect of Narendranath's singing on Ramakrishna is narrated as a telling incident. Ramakrishna accompanied by Ramalal visited Narendranath who was staying at Ramtanu Bose lane in Calcutta when his friends were also present. Ramakrishna met Narendranath in an emotionally choked condition, since he had not met him for quite some time. After feeding Narendranath sandesh (a popular sweet preparation of Bengal) that he brought for him, with his own hands, Ramakrishna asked him to sing a song for him. Narendranath then sang the song “Jago ma Kulakundalini” to the accompaniment of tanpura (which he tuned for his singing). As soon as he heard the song, Ramakrihna went into a state of trance and became very stiff, which was a state of Bhava Samadhi also called Savikalpa Samadhi. Narendra continued singing for a long time. After he stopped singing, Ramakrishna came out of his trance and asked Narendra to visit him at Dakshineswar. Narendra readily complied.[46]

As Narendra tested Ramakrishna, Ramakrishna too took tests of Narendra. One day, Narendra found he was being ignored by Ramakrishna. When he entered the room, Ramakrishna neither greeted nor looked at him. This continued for one month. Ramakrishna had thoroughly ignored Narendra and after one month he asked Narendra— "I have not exchanged a single word with you all this time, and still you come?" Narendra replied that he was still coming because he loved him and not to get his attention. Ramakrishna was very happy with this answer.[47]

Ramakrishna wanted to transfer his supernatural powers to Narendra, but, Narendra denied accepting them. He said he wanted to strive for God realization. He said— "Let me realize God first, and then I shall perhaps know whether or not I want supernatural powers. If I accept them now, I may forget God, make selfish use of them, and thus come to grief." Ramakrishna was once more very much pleased with his disciple's reply.[33]

Death of Vishwanath Datta

[edit]In February 1884, when Narendra was preparing for his upcoming B.A. examinations, his father Vishwanath Datta died.[48] His father's sudden death left the family bankrupt; creditors began demanding the repayment of loans, and relatives threatened to evict the family from their ancestral home. Narendra, once a son of a well-to-do family, became one of the poorest students in his college.[49] He unsuccessfully tried to find work and questioned God's existence,[50] but found solace in Ramakrishna and his visits to Dakshineswar increased.[51][52]

Prayer to goddess Kali

[edit]On the 16th of September, Narendra requested Ramakrishna to pray to goddess Kali, the Divine Mother, for some money, which was the immediate need of Datta family. Ramakrishna asked him to go to the idol of Kali and ask it himself. Following the suggestion, Narendra went to the temple of Kali in the night and stood in front of the idol. He bowed to goddess Kali, but forgot to pray for wealth. When Ramakrishna learned of this, he again sent Narendra to pray. Narendra went to the temple for the second time the same night to pray to goddess Kali, but, not for wealth or property. He prayed for "wisdom, discrimination, renunciation and Her uninterrupted vision".[53][54]

Ramakrishna's illness and death

[edit]In 1885, devotees helped Ramakrishna, who developed throat cancer, to get out of Dakshineswar and he was initially transferred to Calcutta and (later) to a garden house in Cossipore.[55] Narendra and Ramakrishna's other disciples took care of him during his last days, and Narendra's spiritual education continued. At Cossipore, he experienced Nirvikalpa samadhi.[56] Narendra and several other disciples received ochre robes from Ramakrishna, forming his first monastic order.[57] He was taught that service to men was the most effective worship of God.[56] Ramakrishna asked him to care for the other monastic disciples, and in turn asked them to see Narendra as their leader.[58][59]

Two days before the death of Ramakrishna, Narendra was standing beside the bed of Ramakrishna when a thought suddenly came to his mind, "was this person really an incarnation of God?" Narendra thought, but could not find an answer to this question. Suddenly Narendra noticed the lips of Ramakrishna, who was lying ill on the bed, moving, he slowly uttered— "He who in the past was born as Rama and Krishna is now living in this very body as Ramakrishna — but not from the standpoint of your Vedanta."[60]

Ramakrishna died in the early-morning hours of 16 August 1886 in Cossipore.[59][61] He was cremated on the bank of the Ganges. One week later, when Narendra was walking outside the Kali temple of Dakshineswar, he reportedly saw a luminous figure, which he identified as Ramakrishna.[61]

After the death of Ramakrishna

[edit]

After the death of Ramakrishna in August 1886, Narendra and a few other monastic disciples of Ramakrishna converted a dilapidated house at Baranagar into a new math (monastery).[63][64] Between 1888 and 1893, Narendranath travelled all over India as a Parivrajaka Sadhu, (a wandering monk), and visited many states and holy sites.[65][66]

In 1888 Narendra went to Ghazipur and met Pavhari Baba, an ascetic and Hatha yogi. Pavhari Baba used to live in his underground hermitage in his house, where he used to practise meditation and Yoga for days. Baba had influence upon Narendra, and Narendra desired to be initiated by Baba. But the night before the religious initiation by Baba, Narendra reportedly saw a dream in which he saw his master Ramakrishna looking at him with a melancholic face. This dream made him understand that no one other than Ramakrishna could be his teacher: he gave up the idea of becoming Baba's disciple.[67][68]

Ramakrishna's influence on Vivekananda

[edit]Vivekananda considered Ramakrishna as an incarnation of God. In a letter in 1895, he wrote that in Ramakrishna there was "knowledge, devotion and love — infinite knowledge, infinite love, infinite work, infinite compassion for all being".[69] He further said Ramakrishna had the head of Adi Shankara and the hearts of Ramanuja and Chaitanya.[70] He considered it his good fortune that he could see the man so close.[70] He owed everything to Ramakrishna. He said—[71]

All that I am, all that the world itself will some day be, is owing to my Master, Shri Ramakrishna, who incarnated and experienced and taught this wonderful unity which underlies everything, having discovered it alike in Hinduism, in Islam, and in Christianity.

He also said—[72]

If I have told you one word of truth, it was his and his alone, and if I have told him many things which were not true, which were not correct, which were not beneficial to the human race, they were all mine, and on me is the responsibility.

It is said that while Ramakrishna was the spiritual fountainhead of the Ramakrishna Order, his disciple was the propagator par excellent with his exuberant oratorical skills and handsome visage.[73]

Vivekananda's literary works dedicated to Ramakrishna

[edit]Vivekananda delivered two lectures in New York and England in 1901 on Ramakrishna, which were later compiled into a book — My Master.[74] He also wrote a song Khandana Bhava–Bandhana in which he prayed to Ramakrishna to free himself from the bondage and suffering from the world.[75][76]

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Narendranath Datta was named Swami Vivekananda in 1893 by Ajit Singh of Khetri

- ^ The largest pond in the area.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Jackson 1994, p. 19.

- ^ Jackson 1994, pp. ix–xi.

- ^ Jackson 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b Badrinath 2006, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 11–14.

- ^ a b Prabhananda 2003, p. 232.

- ^ Banhatti 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 2–10.

- ^ a b Kishore 2001, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Nikhilananda 1953, p. 14.

- ^ a b Badrinath 2006, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 43.

- ^ Rangachari 2011, p. 61.

- ^ a b Bhuyan 2003, p. 6.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Rana & Agrawal 2005, p. 21.

- ^ a b Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Ghosh 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Badrinath 2006, p. 18.

- ^ a b Kishore 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Badrinath 2006, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Nikhilananda 1953, p. 15.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Nikhilananda 1953, p. 16.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 44.

- ^ Goel 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Kripal 1998, p. 213.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Sen 2010, p. 94.

- ^ Verma 2009, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e Nikhilananda 1953, p. 17.

- ^ a b Nikhilananda 1953, p. 20.

- ^ Dhar 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Kishore 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, p. 19.

- ^ Sandarshanananda 2013, p. 656.

- ^ Sandarshanananda 2013, p. 657.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Rana & Agrawal 2005, p. 39.

- ^ a b Nikhilananda 1953, p. 18.

- ^ Kripal 1998, p. 214.

- ^ a b Sil 1997, p. 37.

- ^ Mookherjee 2002, p. 471.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 57.

- ^ a b Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kishore 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Sil 1997, p. 38.

- ^ Sil 1997, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Kishore 2001, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 76.

- ^ a b Isherwood 1976, p. 20.

- ^ Pangborn & Smith 1976, p. 98.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 31–34.

- ^ a b Rolland 1929, pp. 201–214.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, p. 38.

- ^ a b Nikhilananda 1953, p. 39.

- ^ "Known photographs India 1886 – 1893". vivekananda.net. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, p. 40.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 39–46.

- ^ Kononenko 2010, p. 228.

- ^ Sil 1997, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Nikhilananda 1953, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Wikisource:The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 6/Epistles - Second Series/LXXI Rakhal

- ^ a b Vivekananda & Lokeswarananda 1996, p. 138.

- ^ Vallamattam 1996, p. 1111.

- ^ Vivekananda & Lokeswarananda 1996, p. 140.

- ^ Jackson 1994, p. 22.

- ^ "My Master Sri Sri Ramakrishna Paramhamsa". hinduism.fsnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Ranganathananda, p. 238.

- ^ Chattopadhyay 2001, p. 28.

Sources

[edit]- Badrinath, Chaturvedi (1 January 2006). Swami Vivekananda, the Living Vedanta. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306209-7.

- Banhatti, Gopal Shrinivas (1995). Life And Philosophy Of Swami Vivekananda. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-291-6.

- Bhuyan, P. R. (2003). Swami Vivekananda: Messiah of Resurgent India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0234-7.

- Chattopadhyay, Santinath (2001). Swami Vivekananda: His Global Vision. Punthi Pustak. ISBN 978-81-86791-29-5.

- Chattopadhyaya, Rajagopal (1999). Swami Vivekananda in India: A Corrective Biography. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1586-5.

- Dhar, T.N. (1 January 2006). On The Path Of Spirituality. Mittal Publications. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-8324-133-5.

- Ghosh, Gautam (2003). The Prophet of Modern India: A Biography of Swami Vivekananda. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0149-5.

- Goel, S.L. (1 January 2008). Administrative and Management Thinkers (Relevance in New Millennium). Deep & Deep Publications. p. 94. ISBN 978-81-8450-077-6.

- Isherwood, Christopher (1976). Meditation and Its Methods According to Swami Vivekananda. Hollywood, California: Vedanta Press. ISBN 978-0-87481-030-1.

- Jackson, Carl T. (22 May 1994). Vedanta for the West: The Ramakrishna Movement in the United States. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-11388-7.

- Kishore, B. R. (2001). Swami Vivekanand. Diamond Pocket Books. ISBN 978-81-7182-952-1.

- Kishore, B. R. (1 April 2005). Ram Krishna Paramhansa. Diamond Pocket Books. ISBN 978-81-288-0824-1.

- Kononenko, Igor (27 June 2010). Teachers of Wisdom. Dorrance Publishing. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4349-5410-7.

- Kripal, Jeffrey J. (1 October 1998). Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna. University of Chicago Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-226-45377-4.

- Mookherjee, Braja Dulal (2002). The Essence of Bhagavad Gita. Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-81-87504-40-5.

- Nikhilananda, Swami (1953). Vivekananda: A Biography (PDF). Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. ISBN 0-911206-25-6.

- Pangborn, Cyrus R.; Smith, Bardwell L. (1976). "The Ramakrishna Math and Mission". Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions. Brill Archive. p. 98. ISBN 9789004044951.

- Prabhananda, Swami (2003). "Profiles of Famous educators; Swami vivekananada (1863-1902)" (PDF). UNESCO International Bureau of Education. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Rana, Bhawan Singh; Agrawal, Mīnā Agravāla Meena (2005). The Immortal Philosopher Of India Swami Vivekananda. Diamond Pocket Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-81-288-1001-5.

- Rangachari, Devika (1 January 2011). Swami Vivekananda: A Man with a Vision. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-563-3.

- Ranganathananda, Swami. A Pilgrim Looks at the World. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Rolland, Romain (1929). "The River Re-Enters the Sea". The Life of Ramakrishna. Hollywood, California: Vedanta Press. pp. 201–214. ISBN 978-81-85301-44-0.

- Sandarshanananda, Swami (2013). "Meditation: Its Influence on the Mind of the Future". Swami Vivekananda: New Perspectives An Anthology on Swami Vivekananda. Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 978-93-81325-23-0.

- Sen, Amiya P. (2010). Explorations in Modern Bengal, c. 1800-1900: Essays on Religion, History, and Culture. Primus Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-81-908918-6-8.

- Sil, Narasingha Prosad (1997). Swami Vivekananda: A Reassessment. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-945636-97-7.

- Vallamattam, John (1996). Judgements on minority rights. Commission for Education & Culture, Catholic Bishop's Conference of India.

- Verma, Rajeev (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Hinduism. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. ISBN 9788178357188.

- Vivekananda, Swami; Lokeswarananda, Swami (1996). My India : the India eternal (1st ed.). Calcutta: Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 81-85843-51-1.