Raid on Combahee Ferry

| Raid on Combahee Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Civil War | |||||||

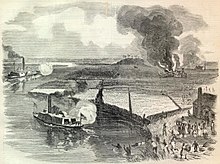

Illustration of the Raid on Combahee River | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Harriet Tubman | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored)[1] | |||||||

The Raid on Combahee Ferry (/kəmˈbiː/ kəm-BEE,[2] also known as the Combahee River Raid) was a military operation during the American Civil War conducted on June 1 and June 2, 1863, by elements of the Union Army along the Combahee River in Beaufort and Colleton counties in the South Carolina Lowcountry.[3]

Harriet Tubman, who had escaped from slavery in 1849 and guided many others to freedom, led an expedition of 150 African American soldiers of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry.[4] The Union ships rescued and transported more than 750 former slaves freed five months earlier by the Emancipation Proclamation, many of whom joined the Union Army.

Background

[edit]Following the first shots of the Civil War at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, the newly formed Confederate States of America quickly moved to defend coastal South Carolina. Union forces tried to take control of the area to secure the fine harbors, which they needed to operate successfully in the South. In November 1861, Union Navy and Army troops invaded Port Royal, south of Charleston near the town of Beaufort. They occupied most of Beaufort County and the Sea Islands.

Planters and overseers fled area plantations ahead of the oncoming Union troops, and their departure effectively liberated thousands of slaves. Several Union Army infantry regiments were formed with these former slaves, including the 2nd South Carolina Infantry under Col. James Montgomery. Montgomery was a guerilla fighter from Kansas who had fought in numerous clashes between pro- and anti-slavery forces there and in Missouri before the war. His style of warfare became common in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. In 1862 Tubman had been assigned to Beaufort to help teach and nurse the former slaves on the Sea Islands.

In the spring of 1863, Union commanders began planning raids into the fortified upper reaches of South Carolina's coastal rivers, such as the Combahee, Ashepoo, and Edisto. The objectives were to remove torpedoes (mines) from the river, seize supplies from area plantations, and destroy the plantations. In addition, the Union forces were to encourage recruits for infantry regiments among any healthy adult male slaves freed by these actions.[5]

The Combahee Ferry raid

[edit]On the evening of June 1, 1863 three small ships (Sentinel, Harriet A. Weed, and John Adams)[a][6] left Beaufort heading for the Combahee. They transported 300 men from the 2nd South Carolina, commanded by Colonel Montgomery, with Company C of the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery manning the ships' guns. Well known abolitionist Harriet Tubman accompanied the troops. Shortly after leaving Beaufort, the Sentinel ran aground in St. Helena Sound.

About three o'clock in the morning of the same June 2, the two remaining ships arrived at the mouth of the Combahee River at Fields Point, where Montgomery landed a small detachment under Captain Thompson. They drove off several Confederate pickets and advanced up the river. Some of the fleeing Confederates rode to the nearby village of Green Pond to sound the alarm. Meanwhile, a company of the 2nd South Carolina under Captain Carver landed two miles above Fields Point at Tar Bluff and deployed into position. The two ships steamed upriver to the Nichols Plantation, where the gunboat Harriet A. Weed anchored.

Carrying the remainder of the 2nd South Carolina and Tubman, the John Adams went upriver to Combahee Ferry, where a temporary pontoon bridge spanned the river. As the Union ship approached, several mounted Confederates rode over the bridge in the direction of Green Pond. The John Adams fired a few shells at them. Troops deployed from the ship set fire to the bridge. Captain Hoyt took his men to the far side, while Captain Brayton, of the 3rd Rhode Island, proceeded up the left riverbank to the Middleton plantation, "Newport", under orders to confiscate all property and lay waste to what could not be carried off.

The John Adams steamed upriver for a short distance until forced to stop by obstructions and pilings. Turning back, she tied up at the causeway. Although Confederate troops stationed at Green Pond were notified of the raid, they did not respond at first. Because of diseases endemic in the Lowcountry during the summer "sick season", such as malaria, typhoid fever, and smallpox, officers had pulled back most Confederate troops from the rivers and swamps, leaving only small detachments. Before this raid, the Confederates had received a false alarm, so the few remaining outposts were cautious about responding to reports of ships or activity until certain they were Union.

Within a few hours, Confederate reinforcements responded from McPhearsonville, Pocotaligo, Green Pond and Adams Run. Colonel Breeden arrived with a few guns and opened fire on the retiring Union troops headed back across the causeway. The John Adams soon overwhelmed them with its superior firepower, forcing the Confederates from the causeway and back into the woods.

By this time, the rest of Montgomery's troops had torched William Cruger Heyward's plantation and C.T. Lowndes's rice mill. They destroyed the houses, mills, and outbuildings. At Nichols Plantation, all of the buildings were set on fire. Union forces took the stores of commodity rice and cotton, as well as supplies of potatoes, corn, and livestock, and left the plantations as smoking ruins. Hearing reports of Federal advances from Fields Point up to the Stokes (Stocks) Causeway, Confederate commanders sent troops in that direction. Upon arrival, they found the Union forces out of reach. Outgunned and outnumbered, the Southern reinforcements retreated to their previous positions.[7]

Liberation of slaves

[edit]Those slaves working in the fields, unaware of the Emancipation Proclamation, were wary when they first saw the approaching Union ships and troops, but word spread quickly that the forces were there to liberate them. Many ran to the riverbank and begged to be taken on board the ships, despite the efforts of overseers and Confederate soldiers to stop them.[8]

In an 1869 biography of Tubman written by Sarah Hopkins Bradford, Harriet Tubman is quoted:[9]

I nebber see such a sight. We laughed, an' laughed, an' laughed. Here you'd see a woman wid a pail on her head, rice a smokin' in it jus' as she'd taken it from de fire, young one hangin' on behind, one han' roun' her forehead to hold on, t'other han' diggin' into de rice-pot, eatin' wid all its might; hold of her dress two or three more; down her back a bag with a pig in it. One woman brought two pigs, a white one an' a black one; we took 'em all on board; named de white pig Beauregard, and the black pig Jeff Davis. Sometimes de women would come wid twins hangin' roun' der necks; 'pears like I never see so many twins in my life; bags on der shoulders, baskets on der heads, and young ones taggin' behin', all loaded; pigs squealin', chickens screamin', young ones squallin'.

Hundreds of slaves stood on the shore. When the small boats put out to get them, they all wanted to get in at once. After the boats were filled to capacity and beyond, the throng of escapees still ashore held on to the boats to prevent them from leaving, putting the boats in danger of capsizing. Oarsmen tried beating them on their hands, but the freed workers would not let go. The small boats made several trips back and forth to load those who wanted to leave.

The Union ships returned to Beaufort the next day. Soldiers took the freedmen to stay at the First Baptist Church before they were transported to a resettlement camp on St. Helena Island. Due to the efforts in planning and intelligence provided by Tubman and her contacts, more than 750 slaves were freed as a result of Montgomery's raid. Many of the men joined the Union Army.

Newspaper accounts of the raid

[edit]The official Union reports of the raid have never been found. Numerous newspaper accounts reported the raid and included comments by the commanding officers.

The pro-Union Commonwealth of Boston reported:[10]

Colonel Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 black soldiers under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of commissary stores, cotton and lordly dwellings, and striking terror into the heart of rebeldom, brought off nearly 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property, without losing a man or receiving a scratch. It was a glorious consummation.... The colonel was followed by a speech from the black woman who led the raid and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted. For sound sense and real native eloquence her address would do honor to any man, and it created a great sensation.

The pro-Southern Charleston Mercury of South Carolina reported:[11]

We have gathered some additional particulars of the recent destructive Yankee raid along the banks of the Combahee. The latest official dispatch from Gen. WALKER, dated Green Pond, eleven o'clock Tuesday night, and which was received here on Wednesday morning, conveyed intelligence that the enemy had entirely disappeared. It seems that the first landing of the Vandels [sic], whose force consisted mainly of three 'companies, officered by whites, took place at Field Point, on the plantation of Dr. R. L. BAKER, at the mouth of the Combahee River. After destroying the residence and outbuildings, the incendiaries proceeded along the river bank, visiting successively the plantations of Mr. OLIVER MIDDLETON, Mr. ANDREW W. BURNETT, Mr. WM. KIRKLAND, Mr. JOSHUA NICHOLLS, Mr. JAMES PAUL, Mr. MANIGAULT, Mr. CHAS. T. LOWNDES and Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD. After pillaging the premises of these gentlemen, the enemy set fire to the residences, outbuildings and whatever grain, etc., they could find. The last place at which they stopped was the plantation of WM. C. HEYWARD, and, after their work of devastation there had been consummated, they destroyed the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry. They then drew off, taking with them between 600 and 700 slaves, belonging chiefly, as we are informed, to Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD and Mr. C.T. LOWNDES. The residences on these plantations are located at different distances from the river, varying in different cases from one to two miles. On the plantation of Mr. NICHOLLS between 8000 and 10,000 bushels of rice were destroyed. Besides his residence and outbuildings, which were burned, he lost a choice library of rare books, valued at $10,000. Several overseers are missing, and it is supposed that they are in the hands of the enemy.

Aftermath

[edit]The raid was so successful that Union forces adopted its tactics for similar operations. Tubman later said that the only flaw was her choice of clothing in that her green dress had been damaged and torn by excited freedmen boarding the ships. A few weeks later, the 2nd South Carolina and the 54th Massachusetts raided up the river to Darien, Georgia, and left the town in smoldering ruins. The Union wanted to damage the Confederate states' ability to supply food and materials for the war effort.

The Combahee Ferry raid proved the value of black troops in combat and demonstrated Harriet Tubman's intelligence and bravery. After the raid, Confederate forces rushed to complete several small earthworks and batteries to better defend the area. The Union did not threaten the region again until the march through the Carolinas by General William T. Sherman in early 1865. The abandoned plantations surrounding Combahee Ferry were not rebuilt during the war; the South went without needed supplies and many of the planters were virtually bankrupted. Several plantations remained unoccupied well after the war.[12]

The raid lent its name to the Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist organization active in the 1970s.

The Combahee Ferry area today

[edit]The location of the Combahee River raid was identified to state and Federal officials by Jeff Grigg prior to a survey related to a bridge replacement project across the Combahee River on U.S. Highway 17. The general area remains in much the same condition as it was during the war, and the causeway is on the same alignment.[13] In 2006, the South Carolina legislature approved a resolution authored by State Representative Kenneth Hodges to name the new bridge after Harriet Tubman in recognition of her role in the historic raid.[14] Also the site of a 1782 Revolutionary War battle,[15] the immediate area has been proposed as a historic district.[16]

The site can be viewed from the boat landing parking lot on the Beaufort side of the river. The surrounding area is under private ownership.

In popular culture

[edit]- The raid was covered in a segment on Drunk History in 2015.[17]

- The raid was also a major plot point of "The General", the penultimate episode of the second season of Timeless, in 2018.

- The Combahee River Raid forms the basis for the 2019 novel The Tubman Command, by historian Elizabeth Cobbs.

- The raid was depicted briefly in the epilogue of the 2019 movie Harriet.

- On January 12, 2024 a 15-foot-tall sculpture of Harriet Tubman in her role as "Civil War hero and the first woman to lead an armed military operation in the United States" was selected to be sited at Philadelphia City Hall. The artist, Alvin Pettit, designed a statue he named A Higher Power: The Call of a Freedom Fighter, which he reported was "... inspired by the 1863 'Raid at Combahee Ferry,' when Tubman led 150 Black Union soldiers into battle and rescued more than 700 slaves."[18]

- A statue of Tubman is to be dedicated on June 1, 2024, in Beaufort, South Carolina.[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ These were converted ferries. The John Adams is not to be confused with the USS John Adams, a naval frigate.

References

[edit]- ^ Linger, Megan (December 10, 2020). "Harriet Tubman and the 54th Massachusetts". Boston African American National Historic Site. National Park Service.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary, Third Edition (Merriam-Webster, 1997; ISBN 0877795460)

- ^ Official Records, Series 1, Volume 14. p. 306.

- ^ "The Combahee Ferry Raid". National Museum of African American History and Culture. May 10, 2017.

- ^ Official Records, Series 1, Volume 14, p. 308.

- ^ Donnelly, Paul (June 8, 2013). "Harriet Tubman's Great Raid". New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "Combahee Raid", Who Lived This History?, Lowcountry Africana

- ^ "Harriet Tubman's Civil War Campaign", W.E.B. Du Bois Learning Center, Kansas City, Missouri, extracted from Kate Clifford Larson, Bound For The Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait Of An American Hero, pp. 212–214, accessed 27 January 2011.

- ^ Sarah Hopkins Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, Auburn [N.Y.]: W.J. Moses, printer, 1869, p. 39, online at Documents of the American South, University of North Carolina. Archived from the original as of 16 December 2016. Accessed on 1 December 2019.

- ^ The Commonwealth, Boston, Massachusetts, July 10, 1863, Harriet Tubman Website

- ^ The Enemy's Raid on the Banks of the Combahee, June 4, 1863

- ^ "Freedmen's Bureau Land Reports, Combahee Ferry, 1865", Lowcountry Africana

- ^ Topozone map of the historical site of Combahee Ferry

- ^ Paras, Andy. "Bridge brings focus on Tubman". Harriet Tubman. Harriet Tubman Historical Society. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Battle of Combahee Ferry

- ^ South Carolina Department of Transportation page for Combahee Ferry Historic District

- ^ "Watch: Octavia Spencer is 'Dope as Hell' as Harriet Tubman in New 'Drunk History' Video". September 24, 2015.

- ^ Sharber, Cory. "Philadelphia Art Commission Approves Work to Begin on Harriet Tubman Statue". WHYY-FM. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Drew (May 31, 2024). "6 Years in the Making, Harriet Tubman Monument to Be Unveiled. Here Are the Plans". The Island Packet. Hilton Head, South Carolina. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Fields-Black, Edda L. (2024), Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War. Oxford University Press.

- Reviews:

- Bellows, Amanda Brickell, "'Combee' Review: Harriet Tubman, Fighting for Freedom", The Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2024

- Herschthal, Eric, "Harriet Tubman and the Most Important, Understudied Battle of the Civil War", The New Republic, February 23, 2024.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

External links

[edit]- Who Lived This History? Combahee Raid, Lowcountry Africana

- Blakemore, Erin (September 8, 2021). "Five Women Veterans Who Deserve to Have Army Bases Named After Them". Smithsonian. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- 1863 in South Carolina

- Battles of the Lower Seaboard Theater and Gulf Approach of the American Civil War

- Beaufort County, South Carolina

- Colleton County, South Carolina

- History of slavery in South Carolina

- June 1863 events

- Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

- Military operations of the American Civil War in South Carolina

- Raids of the American Civil War

- Union victories of the American Civil War