Qiupanykus

| Qiupanykus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Alvarezsauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Parvicursorinae |

| Genus: | †Qiupanykus Lü et al., 2018 |

| Type species | |

| †Qiupanykus zhangi Lü et al., 2018

| |

Qiupanykus (IPA: /ˌtɕʰuˈpaːˈnɑ͡ikəs/, meaning "claw from the Qiupa Formation") is an extinct genus of alvarezsaurid theropod from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Henan Province, China. The type and only species is Q. zhangi, named for Shuancheng Zhang, who assisted in finding the fossils of Qiupanykus.[1]

Discovery

[edit]

The Qiupa Formation is located in the Tantou Basin which is in Luanchuan County of the Henan province in China. Lithological correlation of the local strata has dated the Qiupa Formation to the Late Cretaceous.[1] More specific analyses have suggested that the formation dates to the end of the Maastrichtian stage, which was the final stage of the Mesozoic Era.[2] This would make Qiupanykus and its contemporaries were among the last-surviving non-avian dinosaurs.[3]

The Qiupa Formation preserves a wide variety of dinosaur eggs, many of which have been named as ootaxa, as well as body fossils. Alvarezsaurid remains were found near the village of Guanping in Luanchuan County and were reported in the scientific literature in 2012 and 2017, but the latter of these would not be described until the next year.[4][2] The holotype, and only specimen of what would later be named Qiupanykus was prepared and stored at the Henan Geological Museum in Zhengzhou after being excavated and was given the designation 41HIII-0101. A full description was published in 2018 by Lü Junchang, Li Xu, Chang Huali, Jia Songhai, Zhang Jiming, Gao Diansong, Zhang Yiyang, Zhang Chengjun, and Ding Fang in the journal of the Chinese Geological Survey. A second specimen from the Qiupa Formation, given the designation 41HIII-0104, was suggested to be a new taxon, but was not named or fully described.[1]

Description

[edit]Qiupanykus, like all members of Parvicursorinae, was a relatively small dinosaur, and likely among the smallest of all the alvarezsaurs.[5] The authors of its description did not publish a detailed estimate of its in-life linear size, but they did provide the length of the leg bones. The femur was about 74.2 mm (2.92 in) long, the tibia was about 98.6 mm (3.88 in) long, and the longest metatarsal was about 75.4 mm (2.97 in). This would give the leg, if fully extended, a total length of only about 24.8 cm (9.8 in). Lü and colleagues also used the dimensions of the femur to estimate an in-life mass of 0.52 kg (1.1 lb) based on isometric scaling methods.[1] Subsequent authors studying the evolution of miniaturization in alvarezsaurids gave a mass estimate of only 0.58 kg (1.3 lb) for Qiupanykus.[6] Another publication suggested a range of 0.27–0.91 kg (0.60–2.01 lb) for possible masses.[5]

The holotype of Qiupanykus consists of a relatively poorly-preserved postcranial skeleton that includes elements from all areas of the body. The elements present include four disarticulated cervical vertebrae, six sacral vertebrae, twenty-five caudal vertebrae with an associated chevron, part of the right ilium and ischium, part of the pubis, an articulated right hindlimb (including the femur, fibula, tibia, astragalus, calcaneum, and all three metatarsals), two digits of the foot, and three associated pedal claws. Notably, the skeleton was also found in association with several fragments of eggshells which have been assigned to the ootaxon Arriagadoolithus.[1]

The presence of these features allowed Lü and colleagues to distinguish Qiupanykus from all other alvarezsaurs by the following combination of traits: a strong keel on the underside of the sacral vertebrae, transverse processes positioned on the midline of the centra of the caudal vertebrae at the base of the tail, a reduced knob-like pubic peduncle on the ilium, a large quadrangular crest on the tibia, the two vertebrae at the base of the tail being functionally part of the sacrum, and the presence of a small pneumatic foramen on each of the caudal vertebrae. Additionally, the ratio of the length of the femur to the tibia and the presence of an arctometatarsus suggest that Qiupanykus, like other alvarezsaurs, would have been a capable runner.[1]

Classification

[edit]In their description of Qiupanykus, Lü and colleagues conducted a phylogenetic analysis of Alvarezsauroidea. This analysis, based on the dataset published by Xu Xing in 2011, included 14 taxa coded for 77 anatomical characters. Their strict consensus tree recovered Qiupanykus at the base of Parvicursorinae in a polytomy with Albertonykus, Linhenykus, Xixianykus, the specimen YPM 1049 ("Ornithomimus minutus"), and a clade containing the rest of the derived parvicursorines.[1] Although not formally assigned to the clade Parvicursorinae in the description, this position would make it a member of Parvicursorinae sensu Xu et al. (2013).[7]

In 2024, a team of authors led by Jorge Gustavo Meso and including the theropod researchers Diego Pol and Peter Makovicky published a study examining the evolutionary history of Alvarezsauria. They studied the biogeography, diversification, and functional morphology of these theropods throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. The phylogenetic analysis conducted by these authors reaffirmed the findings of Lü and colleagues. They found Qiupanykus as a member of Parvicursorinae and suggested that its appearance is reflective of a "miniaturization event" within alvarezsaurian evolution that occurred during the early-to-middle Cenomanian. An abbreviated version of the cladogram produced by Meso and colleagues is shown below.[6]

| Alvarezsauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

[edit]The ootaxon found in association with Qiupanykus, given the name Arriagadoolithus, has been suggested by multiple authors to possibly have been laid by Qiupanykus, even if not necessarily the individual which was preserved. Lü and colleagues estimated that in life, the egg would have been more massive than the holotype, making it unlikely that the holotype individual was the egg's parent.[1] However, in their study on the evolutionary trends of alvarezsauroids in 2022, Meso and colleagues observed that episodes of miniaturization in some modern birds has resulted in the evolution of species which lay very small clutches of disproportionately massive eggs. The kiwi bird is the foremost example of this phenomenon as females famously lay a single giant egg (20% the mass of the mother) in every clutch. Eggs found in association with the larger-bodied alvarezsaur Bonapartenykus appear to also be larger than eggs laid by other similarly-sized animals, which Meso and colleagues suggest that this phenomenon could be widespread in alvarezsaurids.[6]

Paleoecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]No remains of the skull of Qiupanykus are known, so no direct observations about its possible feeding habits based on the anatomy of its skull can be inferred. However, the diet of derived alvarezsauroids generally has been a topic of considerable speculation. The major diversification of parvicursorines coincided with the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution — a major evolutionary transition that was marked by, among other things, the spread of angiosperms and the evolution of eusociality in Hymenoptera.[6] These simultaneous developments, coupled with the unique morphology of alvarezsaurid hands, has been used to suggest that they may have been specialized to feed on colonial insects like ants.[8][1]

Importantly for discussions of the diet of Qiupanykus, the holotype was found associated with broken dinosaur eggshells. These egg fossils were originally reported in a conference abstract as belonging to the (then unnamed) alvarezsaurid.[9] These eggshells, later given the name Arriagadoolithus, closely resemble elongatoolithid eggs found at Luanchuan County elsewhere in the Qiupa Formation that are attributed to oviraptorosaurs. This is supported by the discovery of fossils from juvenile oviraptorosaurs in the vicinity of Qiupanykus. Also of note, the scaling methods used to estimate the full size of these eggshells, yielded a mass of about 1,136 g (2.504 lb), which is larger than the estimated mass of the holotype of Qiupanykus.[1]

These lines of evidence seem to indicate that the egg almost certainly could not have belonged to this Qiupanykus individual. Lü and colleagues use this to suggest that Qiupanykus, and possibly alvarezsaurs more generally, fed on the eggs of oviraptorosaurs and other dinosaurs. They also suggested that the large hand claws on their short arms would have assisted in breaking eggshells to feed. Additional evidence which may support this hypothesis is the discovery of eggshell fossils in the vicinity of the alvarezsaur Bonapartenykus in Patagonia.[1] Subsequent authors have suggested that it should not be ruled out that the egg belonged to Qiupanykus.[6]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]The Qiupa Formation is subdivided into three sections laterally, which correspond to different outcroppings of the rock layer. Section C, in which Qiupanykus was found, is the youngest of these sections, and this section preserves strata that correspond exactly to the K-T boundary and the beginning of the Cenozoic. The fossil-bearing strata of the Qiupa Formation where Qiupanykus was found are the lower beds of Section C. These beds are composed primarily of purple-red calcareous mudstone and fine to medium conglomerates with interbedded calcareous mudstone. This sedimentary layer would have been deposited by a braided river delta that created the depositional environment necessary for fossils to form.[2] This area is also interpreted as having been part of a coastal environment during the end of the Cretaceous Period.[4]

Contemporary fauna

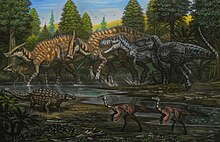

[edit]The Qiupa Formation is very fossil rich, although relatively few taxa from the area have been described and named.[2] The largest inhabitants of the area were the non-avian dinosaurs. Remains of large dinosaurs are fragmentary and indeterminate in identity, with many of them only being diagnostic to the family level. Partial remains from the area have been attributed to ankylosaurids and tyrannosaurids, and one of these was even named: the dubious "Tyrannosaurus luanchuanensis".[2] More complete remains are known from small theropods. Qiupanykus was contemporaneous with the ornithomimid Qiupalong,[10] the dromaeosaur Luanchuanraptor,[2] indeterminate troodontids,[10] the oviraptorid Yulong,[11] and at least one other alvarezsaur taxon.[1] This environment was also home to a variety of other animals. These would have included turtles, lizards (such as the genus Tianyusaurus), small mammals, and uniquely an edentulous enantiornithine Yuornis.[2][12]

See also

[edit]- 2018 in archosaur paleontology

- List of Asian dinosaurs

- List of vertebrate fauna of the Maastrichtian stage

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lü, JC; Xu, L; Chang, HL; Jia, SH; Zhang, JM; Gao, DS; Zhang, YY; Zhang, CJ; Ding, F (2018). "A new alvarezsaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Luanchuan, Henan Province, central China". China Geology. 1: 28–35. doi:10.31035/cg2018005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jiang, X.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Ji, S.-A.; Zhang, X.-L.; Xu, L.; Jia, S.-H.; Lü, J.-C.; Yuan, C.-X.; Li, M. (2011). "Dinosaur-bearing strata and K/T boundary in the Luanchuan-Tantou Basin of western Henan Province, China". Science China Earth Sciences. 54 (1149). doi:10.1007/s11430-011-4186-1.

- ^ Han, Fei; Wang, Qiang; Wang, Huapei; Zhu, Xufeng; Zhou, Xinying; Wang, Zhixiang; Fang, Kaiyong; Stidham, Thomas A.; Wang, Wei; Wang, Xiaolin; Li, Xiaoqiang; Qin, Huafeng; Fan, Longgang; Wen, Chen; Luo, Jianhong; Pan, Yongxin; Deng, Chenglong (2022). "Low dinosaur biodiversity in central China 2 million years prior to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (39). Bibcode:2022PNAS..11911234H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2211234119. PMC 9522366. PMID 36122246.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Graeme (2019). "Guanping, Qiupa Town (Cretaceous of China)". The Paleobiology Database.

- ^ a b Qin, Zichuan; Zhao, Qi; Choiniere, Jonah N.; Clark, James M.; Benton, Michael J.; Xu, Xing (2021). "Growth and miniaturization among alvarezsauroid dinosaurs". Current Biology. 31 (16): 3687–3693.e5. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E3687Q. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.013. PMID 34233160.

- ^ a b c d e Meso, Jorge Gustavo; Pol, Diego; Chiappe, Luis; Qin, Zichuan; Díaz-Martínez, Ignacio; Gianechini, Federico; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Makovicky, Peter J.; Pittman, Michael (2025). "Body size and evolutionary rate analyses reveal complex evolutionary history of Alvarezsauria". Cladistics. 41 (1): 135–155. doi:10.1111/cla.12600. PMC 11811816. PMID 39660404.

- ^ Xu, X.; Upchurch, P.; Ma, Q.; Pittman, M.; Choiniere, J.; Sullivan, C.; Hone, D.W.E.; Tan, Q.; Tan, L.; Xiao, D.; Han, F. (2013). "Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarezsauroid biogeography". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (1): 25–46.

- ^ Senter, P. (2005). "Function in the stunted forelimbs of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda), a dinosaurian anteater". Paleobiology Vol. 31, No. 3 pp. 373–381.

- ^ Kundrát M, Lü JC, Xu L, Pu HY, Shen CZ, Chang HL. 2017. First assemblage of eggshells and skeletal remains of the alvarezsaurid dinosaur from Laurasia (Upper Cretaceous, China). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology abstracts, 145.

- ^ a b Li Xu; Yoshitsugu Kobayashi; Junchang Lü; Yuong-Nam Lee; Yongqing Liu; Kohei Tanaka; Xingliao Zhang; Songhai Jia; Jiming Zhang (2011). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with North American affinities from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation in Henan Province of China". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 213–222. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.004.

- ^ Lü, Junchang; Currie, Philip J.; Xu, Li; Zhang, Xingliao; Pu, Hanyong; Jia, Songhai (2013). "Chicken-sized oviraptorid dinosaurs from central China and their ontogenetic implications". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (2): 165–175. Bibcode:2013NW....100..165L. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-1007-0. PMID 23314810.

- ^ Xu, Li; Buffetaut, Eric; o'Connor, Jingmai; Zhang, Xingliao; Jia, Songhai; Zhang, Jiming; Chang, Huali; Tong, Haiyan (2021). "A new, remarkably preserved, enantiornithine bird from the Upper Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Henan (Central China) and convergent evolution between enantiornithines and modern birds". Geological Magazine. 158 (11): 2087–2094. doi:10.1017/S0016756821000807.