Proposed Croat federal unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

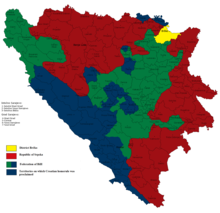

The Croat federal unit, Croat entity, or third entity (Serbo-Croatian: Hrvatska federalna jedinica, Hrvatski entitet, Treći entitet), is a proposed federative unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina encompassing areas populated by Croats, to be created by the partition of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina into Croat and Bosniak entities. The proposal is supported by the Croatian National Assembly, which includes the electoral representatives of Bosnian Croats. However, a detailed plan for its partition, including its borders, has yet to be finalized.[1]

Since Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into two entities, the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska and the Bosniak-majority Federation, Croats, as one of the three theoretically equal constitutive nations, have proposed dividing the Federation into Bosniak and Croat federative entities.[2][3][4] Advocates for a Croat federal unit argue it would ensure Croat equality and render unnecessary complex ethnic quota systems at both the Federation and state level. Opponents have argued that it would further entrench ethnic division and engender separatism.

Background

[edit]This section possibly contains unsourced predictions, speculative material, or accounts of events that might not occur. Information must be verifiable and based on reliable published sources. |

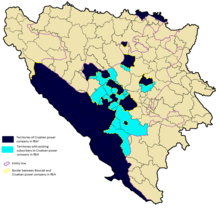

Bosnian War and Herzeg-Bosnia

[edit]During the Bosnian War (1992–95), Bosnian Croats founded their own sub-national entity, the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, which functioned as a quasi-state, notionally being an autonomous region within the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It possessed its own institutions and state administration, including armed forces (the Croatian Defence Council), a president, prime minister, and legislative assembly. However, following the Dayton Agreement, it was dissolved into the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1996.

Peace plans

[edit]

During the Bosnian War, international mediators and envoys proposed several peace plans that included forming three federal units in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1992, EC diplomat José Cutileiro sketched a proposal in which he stated that the three constituent units would be "based on national principles and taking into account economic, geographic, and other criteria".[5] In late July 1993, representatives of Bosnia and Herzegovina's three warring factions entered into a new round of negotiations. On 20 August, the UN mediators, Thorvald Stoltenberg and David Owen, unveiled a map that would organise Bosnia and Herzegovina into three ethnic mini-states. Bosnian Serb forces would be given 52% of Bosnia-Herzegovina's territory, Muslims would be allotted 30 percent and Bosnia Croats would receive 18 percent. Sarajevo and Mostar would be districts belonging to none of the three states. On 29 August 1993 the Bosniak side rejected the plan.

(Con)federal structure

[edit]In 1994, under the Washington Agreement, Croats joined their territory, Herzeg-Bosnia, with the Bosniak-government controlled areas (the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina) to create a subnational entity, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) with joint institutions. The 1995 Dayton Agreement that ended the war left the country divided into two political entities, the Serb-dominated and controlled Republika Srpska and the Bosniak-Croat Federation. FBiH was further divided into 10 autonomous cantons to ensure equality. The FBiH government and a bicameral Parliament were supposed to guarantee power-sharing and equal representation to the less numerous Croats. Some dissatisfaction with this situation was displayed by Croats already in 1999 together with the calls for an establishment of a Croat-majority federal unit, but the Croat member of the state presidency dismissed it and called for strengthening of the principle of equality of three communities and of canton autonomy.[6]

Federation

[edit]

In 2001, the Office of the High Representative (OHR) in the country imposed amendments to the Federation's constitution and its electoral law, complicating its structure and impairing the parity between Bosniaks and Croats that was up until then in force in the Federation. Since Bosniaks compose roughly 70.4% of FBiH's population, Croats 22.4% and Serbs just around 2%, the Parliament's House of Peoples (with equal representation for the nationalities) is supposed to ensure that the interests of Croats, Serbs and national minorities are fairly represented during government creation and in the legislative process. However, ever since 2001–02 and foreign-imposed amendments to the constitution and electoral laws, Croats have claimed that the election system for the deputies in the House of Peoples is unfair, depriving them of their rights to representation and in fact enabling Bosniaks to control the majority in the upper house as well. Namely, after 2002 each nation's deputies to the House of Peoples are elected by 10 Cantonal assemblies, the majority of which (6) is controlled by Bosniak politicians. This dismantled checks and balances the Federation's Croats and Serbs had on the Federal legislature as well as the executive, particularly government-building. In 2010-14 Federation's Government was formed and Federation's president appointed without the consent of Croat deputies in the House of Peoples, receiving just 5 votes of confidence out of 17. In March 2011 country's Central Electoral Commission declared HoP's composition and decisions to be illegal, but the High Representative Valentin Inzko suspended CEC's decision.[7] After Bosnian Croat politician Božo Ljubić filed an appeal, in December 2016 the Constitutional Court found the election system of the deputies in the House of Peoples unconstitutional and abrogated the controversial rules.[8]

In 2005 Croat member of the country's tripartite Presidency Ivo Miro Jović said "I don't mean to reproach Bosnian Serbs, but if they have a Serb republic, then we should also create a Croat republic and Bosniak (Muslim) republic". The Croat representative in the federal Bosnian Presidency, Željko Komšić, opposed this, but some Bosnian Croat politicians advocated for the establishment of a third (Croatian) entity.[9]

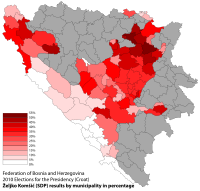

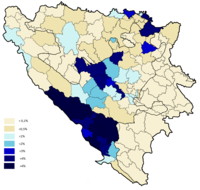

Another issue Croats raised is the election of Croat member of the country's Presidency. Namely, every citizen in the Federation can decide whether to vote for a Bosniak or a Croat representative. However, since Bosniaks make up 70% of Federation's population and Croats only 22%, a candidate running to represent Croats in the Presidency can be effectively elected even without a majority among the Croat community - if enough Bosniak voters decide to vote on a Croat ballot. This happened in 2006 and in 2010, when an ethnic Croat, Željko Komšić, backed by multiethnic Social-Democrat Party, won the elections with very few Croat votes.[10][11] In 2010 he didn't win in a single municipality that had Croat-majority or plurality; nearly all of these went to Borjana Krišto. Bulk of the votes Komšić received came from predominantly Bosniak areas and he fared quite poorly in Croat municipalities, supported by less than 2,5% of the electorate in a number of municipalities in Western Herzegovina, such as Široki Brijeg, Ljubuški (0,8%), Čitluk, Posušje and Tomislavgrad, while not being able to gain not even 10% in a number of others.[12] Furthermore, total Croat population in whole of Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was then estimated around 495,000;[13] Komšić received 336,961 votes alone, while all other Croat candidates won 230,000 votes altogether. Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina consider him to be an illegitimate representative and generally treat him as a second Bosniak member of the presidency.[14][15][16][17] This raised frustration among Croats, undermined their trust in federal institutions and empowered claims for their own entity or a federal unit.[18] In addition to that, two minorities' representatives appealed to the European Court of Human Rights since they cannot run for state presidency due to their ethnic background (being neither of the three constitutive nations) and won the case. EU asked Bosnia and Herzegovina to implement the ruling, named Sejdić-Finci, which would require changing electoral laws and perhaps the constitution.

Croat political parties also complain about the lack of a public broadcasting system in Croatian, focused on the Croatian community,[19][20] as well as about unequal funding their cultural and education institutions receive in the Federation. The largest town with Croat majority, Mostar, with a sizeable Bosniak minority, has been in a gridlock since 2008 since the two communities cannot agree on the electoral rules for local elections.[21]

Dissatisfied with the representation of Croats in the Federation, Croat political parties insist on creating a Croat-majority federal unit instead of several cantons. SDA and other Bosniak parties strongly oppose this.[22] In January 2017, Croatian National Assembly stated that "if Bosnia and Herzegovina wants to become self-sustainable, then it is necessary to have an administrative-territorial reorganization, which would include a federal unit with a Croatian majority. It remains the permanent aspiration of the Croatian people of Bosnia and Herzegovina."[23]

Croatian Self-Rule

[edit]

In 2000, the Office of the High Representative in the country imposed amendments to the Federation's constitution and its electoral law, which complicated its structure and impaired the parity between Bosniaks and Croats that had been in force. Dissatisfied Croat politicians set up a separate Croatian National Assembly, held a referendum parallel to the elections and proclaimed Croatian federal unit in Croat-majority areas in the Federation (Croatian Self-Government or Self-Rule, Hrvatska samouprava). The Federation was declared obsolete and Croat soldiers in Federation's Army and Croat customs and police officers were asked to pledge allegiance.

Croatian Self-Rule was supposed to be a temporary solution until the controversial amendments and election rules are overturned. The attempt ended shortly after a crackdown by SFOR and judiciary proceedings.

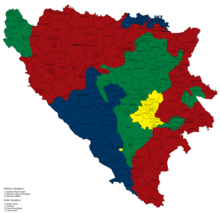

Since 2001

[edit]Since 2001, various Croatian politicians and parties in different electoral cycles have proposed creating a federal unit with a Croatian majority. Sometimes, it is proposed as a federal unit within the Croat-Bosniak Federation, while others have proposed dismantling the Federation into two separate entities, Croat- and Bosniak-majority ones, respectively, and thus ending up with three entities on a national level (the third being current Republika Srpska). One of the few worked-out reform proposals calling for an establishment of a Croat federal unit within the Federation was sketched out before the 2014 general elections by a minor Croat party, Croatian Republican Party (HRS).[24] According to HRS, Croat-majority federal unit would assume the powers and competencies currently held by cantons in the Federation. Federation would continue to exist as a federation of a Croat-majority and a Bosniak-majority canton, together with few mutually shared districts. Federation's bicameral Parliament would be retained; the House of Peoples deputies would be elected in canton and district assemblies by assembly members from respective nations, proportionate to their share in the cantons' population.[25] HRS's proposal:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most prominent Croatian parties (HDZ BiH, HDZ 1990 and HSS), assembled together in Croatian National Assembly, have so far failed to deliver anything more than a mere concept.[1] Dragan Čović, president of one of the main Croatian party in Bosnia, Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, said that "all Croatian parties will propose that Bosnia and Herzegovina be divided into three ethnic entities, with Sarajevo as a separate district. Croatian politicians must be the initiators of a new constitution which would guarantee Croats the same rights as to other constituent peoples. Every federal unit would have its legislative, executive and judiciary organs". He claimed the two-entity system is untenable and that Croats have been subject to assimilation and deprived of basic rights in the federation with the Bosniaks.[26]

In July 2014, the International Crisis Group published a report Bosnia's Future, among others, proposing establishing Croat entity and reorganizing the country in three entities:

There is nothing inherently wrong with a Croat entity. It would solve many problems: there would be no further need for cantons, and relations between state and entity, and between entity and municipality, could be consistent throughout Bosnia. Instead of a tangled federation of entities and peoples, the country would be a normal federation of territorial units, a design with many successful European examples. Ethnic quotas could be replaced by regional representation and protection of fundamental human rights.[27]

— International Crisis Group, Bosnia's Future

Political scientist from Macalester College and Georgetown University, Valentino Grbavac, proposed the establishment of a Croat entity in his 2016 book "Unequal democracy" Archived 15 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine as the optimal solution. He proposed assigning same powers that Republika Srpska currently holds to new Croat and Bosniak entities, possibly changing borders of municipalities to better reflect ethnic composition and turning Jajce into a Croat-Bosniak district, like Brčko today. Croat entity would also "look out for the well-being and protection of Croats in other entities," while introducing "strong legal protection" and "guarantees of rights of other nationalities" in Croat-majority entity.[28]

In his December 2016 essay in the Foreign Affairs, Timothy Less argued that the U.S. foreign policy should accept "the Croats' demand for a third entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the medium term, the United States should allow [the entity] to form close political and economic links with [Croatia], such as allowing dual citizenship and establishing shared institutions" as this would enable the population to "satisfy their most basic political interests."[29] David B. Kanin, an adjunct professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University and a former senior intelligence analyst for the CIA, pointed out in February 2017 that Bosniak politicians' unilateral policy "justifies the Croats' demand for their own entity."[30]

Constitutional principles

[edit]Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina in its landmark Decision on the constituency of peoples ruled that:

Territorial delimitation [of Entities] must not serve as an instrument of ethnic segregation – on the contrary – it must accommodate ethnic groups by preserving linguistic pluralism and peace in order to contribute to the integration of the state and society as such [...] Constitutional principle of collective equality of constituent peoples, arising out of designation of Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs as constituent peoples, prohibits any special privileges for one or two constituent peoples, any domination in governmental structures and any ethnic homogenization by segregation based on territorial separation [...] [D]espite the territorial division of BiH by establishment of two Entities, this territorial division cannot serve as a constitutional legitimacy for ethnic domination, national homogenization or the right to maintain results of ethnic cleansing [...] Designation of Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs as constituent peoples in the Preamble of the Constitution of BiH must be understood as an all-inclusive principle of the Constitution of BiH to which the Entities must fully adhere...[31]

Territory

[edit]

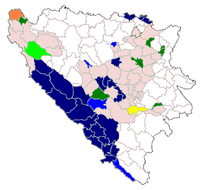

It is unclear what territory Croat federal unit would encompass. It is generally assumed it would comprise Croat-majority municipalities in the country, but the criteria haven't been clearly defined (whether two-thirds majority, absolute majority, or plurality would be required).[32] In some municipalities, especially in Central Bosnia, Croats have a small majority (Vitez, 55%) or just plurality (Mostar 48.4%, Busovača 49.5%). CRP's 2014 proposal assumed that in Central Bosnia, Vitez, Jajce, Busovača, Dobretići, Kiseljak, Kreševo and Novi Travnik together with the eastern, Croat-majority part of Fojnica municipality would become part of the Croat canton, while Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje, Travnik, and Mostar would be districts in Bosniak-Croat condominia.[33] However, this proposal came before the 2013 census results had been published. Contrary to the previously held assumptions, these showed that Jajce and Novi Travnik did not have Croat majority.

Dragan Čović, Croat member of the state Presidency, claimed in 2017 that the Croat entity will encompass "Herzegovina, Posavina, Žepče and parts of Central Bosnia."[34] At the end of 2016 Croat Catholic cardinal Vinko Puljić stated that he believed Croat entity would have to include parts of Republika Srpska territory as well.[35]

Some academic proposals, as well as partially CRP's 2014 proposal (with respect to Fojnica) and somewhat the proclaimed area of Croatian Self-Government in 2001 envisage changing borders of municipalities in mixed Bosniak-Croat areas (Mostar, Central Bosnia) in order to encompass larger share of Croats there.

The International Crisis Group pointed out that the vestiges of Croat territorial autonomy in the Federation exist in the form of the area Archived 25 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine served by the electricity utility Elektroprivreda HZ HB, "which covers most areas of Croat habitation",[36] Croatian Post Mostar, HT Mostar etc. These are areas that were under control of Herzeg-Bosnia and Croatian Defence Council (HVO) in late 1995. In February 2017, Croatian Peasant Party of Bosnia-Herzegovina president Mario Karamatić said HSS will demand a reestablishment of Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia in its 1995 shape if the Republika Srpska secedes.[37] As far as the Herzeg-Bosnia's tentative territory, Karamatić proposed the area served by the electricity utility Elektroprivreda HZ HB.[38]

Demographics

[edit]In February 2017, Croatian-language newspaper in Bosnia, Večernji list, published a proposal for a Croat entity that would include all of the Croat-majority or plurality municipalities (24 in total). Out of 497.883 Croats that live in FBiH, 372.276 or 75% would live in the Croat federal unit.[39] It would have a population of 496.385, with the ethnic breakdown as follows:[40]

- 372.276 Croats (75%)

- 111.821 Bosniaks (22.5%)

- 9.200 Serbs (1.9%)

This would make the Croat entity virtually a symmetric version of the current Federation (70% Bosniak, 22% Croat, 2% Serb). If only the western, Croat-inhabited part of Mostar municipality is included in the entity, this would reduce the number of Bosniaks in the Croat entity by roughly 45,000 and increase Croat majority to 83%. If Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje municipality would be divided into Croat- and Bosniak-majority municipalities to be added to two entities, respectively, Večernji list claims that as much as 83% of Federation's Croats would end up in the Croat federal unit.[39]

Opinion polls

[edit]Share of Croatian or overall population that believes creating a third, Croat entity would be the best solution for Bosnia and Herzegovina:

| Date | Support | Pollster |

|---|---|---|

| November 2016 | 5% FBiH[41] | IMPAQ International |

| November 2015 | 9% FBiH[42] | IMPAQ International |

| June 2014 | 51% Croats[43] | National Democratic Institute |

| October 2013 | 53% Croats[44] | University of Mostar |

| May 2013 | 37.7% Croats 7.7% FBiH[45] |

Prism Research (Sarajevo) |

| Early 2011 | 39% Croats[46] | Friedrich Ebert Stiftung |

| November 2010 | 43% Croats[47][48] | Gallup Balkan Monitor |

| August 2010 | 53% Croats 9% overall[49] |

National Democratic Institute |

| October 2009 | 36% Croats 8% overall[50] |

National Democratic Institute |

| September 2005 | 22% Croats[51] | Prism Research (Sarajevo) |

| May 2004 | 29% Croats[52] | Prism Research (Sarajevo) |

| Early 2004 | 40% Croats[53] | Early Warning Report, UNDP |

See also

[edit]- German-speaking Community of Belgium

- Székely autonomy initiatives

- Constitutional reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Constitutional-law position of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Proposed secession of Republika Srpska

- Bosniak Republic

- Greater Croatia

References

[edit]- ^ a b Danijal Hadžović (9 February 2017). "HDZ-OV PUCANJ U PRAZNO: Mirno spavajte, trećeg entiteta neće biti!". slobodna-bosna.ba (in Serbo-Croatian). Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Pabst, Volker (3 December 2018). "Der serbischstämmige Präsident von Bosnien-Herzegowina lehnt den Staat ab, dem er vorsteht". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in Swiss High German). ISSN 0376-6829. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ "May 2017 Monthly Forecast: Bosnia and Herzegovina". Security Council Report. 28 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Lilyanova, Velina (2015). "Bosnia and Herzegovina: Political parties" (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Glaurdić, Josip (2011). The Hour of Europe: Western Powers and the Breakup of Yugoslavia. London: Yale University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0300166293.

- ^ "Balkan Report: March 17, 1999". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 11 November 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Bosnia and Herzegovina, Freedom in the World in 2012" Archived 6 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Freedom House

- ^ Rose, Eleanor: "Bosnian Court Ruling Lends Weight to Croat Agitation", Balkan Insight, 15 Dec 16

- ^ Staff. "Bosnia: Regionalization proposal on table". B92. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Andrew MacDowall: "Dayton Ain’t Going Nowhere", Foreign Policy, 12 December 2015.

- ^ "News Analysis: Few surprises expected in Bosnian general elections". Xinhua. 3 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010.

- ^ Central Electorate Commission, results in municipalities, 2010

- ^ U BiH ima 48,4 posto Bošnjaka, 32,7 posto Srba i 14, 6 posto Hrvata (Article on the preliminary report of 2013 census) Archived 31 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b International Crisis Group: Bosnia’s Future Europe, Report N°232, 10 July 2014

- ^ Vogel, T. K. (9 October 2006). "Bosnia: From the Killing Fields to the Ballot Box". The Globalist. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Pavić, Snježana (8 October 2010). "Nije točno da Hrvati nisu glasali za Željka Komšića, u Grudama je dobio 124 glasa". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Reforma Federacije uvod je u reformu izbornog procesa" (in Croatian). Dnevno. 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ a b Luka Oreskovic: "Doing Away with Et Cetera" Archived 9 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Policy. 30 October 2013

- ^ Rubina Čengić: "Hrvati insistiraju na svom kanalu", Nezavisne novine, 12 May 2008.

- ^ Samir Huseinović: "U Strazbur po TV-kanal na hrvatskom jeziku", Deutsche Welle, 11 June 2008.

- ^ Bevanda, 2012.

- ^ Bosnia's Future, pp. 37-8

- ^ Rose, Eleanor: "Bosniaks Slap Down Calls for Bosnian Croat Entity", Balkan Insight, 30 January 2017

- ^ Ustavne promjene u Bosni i Hercegovini (PDF) (in Croatian). Bosnia and Herzegovina: HRS Hrvatska Republikanska Stranka. September 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Ustavne promjene u Bosni i Hercegovini (PDF) (in Croatian). Bosnia and Herzegovina: HRS Hrvatska Republikanska Stranka. September 2014. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- ^ "BOSNIA: 'Sanctions if no progress on reform', warns top envoy's deputy". ADN Kronos International. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Ustavne promjene u Bosni i Hercegovini (PDF) (in Croatian). Bosnia and Herzegovina: HRS Hrvatska Republikanska Stranka. September 2014. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Grbavac, Valentino (2016). Unequal Democracy: The Political Position of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina (PDF). Mostar: Institute for social and political research. pp. 166–168. ISBN 978-9958-0379-1-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2024.

- ^ Less, Timothy (20 December 2016). "Dysfunction in the Balkans. Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Kanin, David B. (28 February 2017). "Doing harm". Transconflict. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, U-5/98 (Partial Decision Part 3), para. 26, 54, 57, 60, 61, Sarajevo, 1 July 2000

- ^ Mirjana Kasapović: "PLAN BISKUPA O PREUREĐENJU BiH DOVEO BI DO RATA! Njihov prijedlog je iznimno opasan i prava je sreća da je njihova politička moć - nikakva", Globus, 24 February 2017.

- ^ CRP: Ustavne promjene u Bosni i Hercegovini Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 9 (map)

- ^ "Čović: Treći entitet će činiti Hercegovina, Posavina, srednja Bosna i Žepče", Nezavisne novine, 7 January 2017

- ^ "Cardinal: Croat entity would have to include RS territory", tanjug, b92.net, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2016

- ^ Bosnia's Future, p. 37

- ^ "HSS will demand re-establishment of HR- HB in case of secession of RS", fena.ba, 22 February 2017.

- ^ "Beljak u Mostaru: Hrvati Herceg-Bosne bili su na braniku Hrvatske, a ona ih je ignorirala 100 godina" Archived 23 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, RADIO LJUBUŠKI, 22 February 2017

- ^ a b "Evo koliko bi Hrvata živjelo u većinski hrvatskoj federalnoj jedinici u BiH", vecernji.ba, 6 February 2017

- ^ "JOŠ STATISTIKE: Donosimo nacionalnu strukturu većinski hrvatskog i bošnjačkog entiteta", hms.ba, 6 February 2017

- ^ Carsimamovic Vukotic et al. (March, 2017) Findings from the National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Ye Zhang and Naida Carsimamovic Vukotic (April, 2016) Findings from the National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Jazvić, Dejan. "Hrvati bi htjeli treći entitet, Bošnjaci ukidanje entiteta, a Srbi status quo", Večernji list, 7 August 2014.

- ^ Jukić, Elvira: "Bosnian Croats Want Entity and TV, Poll Says", Balkan Insight, 19 December 2013

- ^ Public opinion poll results - Analitical report for Office of the UN Resident Coordinator in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Prism Research, 2013, pp. 41–42

- ^ Skoko, Božo. "ŠTO HRVATI, BOŠNJACI I SRBI MISLE JEDNI O DRUGIMA A ŠTO O BOSNI I HERCEGOVINI?", Ekstra, 18 April 2011.

- ^ Mabry, T. J., McGarry, J., Moore, M., & O'Leary, B. (Eds.). (2013). Divided nations and European integration. University of Pennsylvania Press., pp. 243, f5.

- ^ Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. Archived 7 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, p. 6

- ^ "Public Opinion Poll Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) August 2010", p. 42

- ^ "Public opinion poll in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) October 2009", p. 37

- ^ Tuathail, G. Ó., O'Loughlin, J., & Djipa, D. (2006). Bosnia-Herzegovina ten years after Dayton: Constitutional change and public opinion. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 47(1), 61–75, p. 68

- ^ Mabry, T. J., McGarry, J., Moore, M., & O'Leary, B. (Eds.). (2013). Divided nations and European integration. University of Pennsylvania Press., pp. 243, f5.

- ^ Nations in Transit - Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005 Archived 6 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Freedom House

Sources

[edit]- Bevanda, Slađan; Bevanda, Slaven; Merdžo, Josip; Vidović, Danijel (17 September 2012). "Memorandum on Croats Position in Mostar to Spanish Embassy in Bosnia and Herzegovina" (PDF). Bljesak.info - Bh. Internet portal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012.

- Grbavac, Valentino (2016). Unequal Democracy: The Political Position of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina (PDF). Mostar: Institute for social and political research. ISBN 978-9958-0379-1-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2024.

- Sitarski, Milan; Vukoja, Ivan (2016). Bosna i Hercegovina - federalizam, ravnopravnost, održivost: studija preustroja BiH u cilju osiguravanja institucionalne jednakopravnosti konstitutivnih naroda. (Bosnia and Herzegovina: a study of BIH redesign to secure institutional equality of constituent peoples) (in Croatian). Mostar: Institute for social and political research. ISBN 978-9958-9185-6-8.

- "Bosnia's Future" (PDF). Europe Report. 232. International Crisis Group. 10 July 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bieber, Florian (2001). "Croat Self-Government in Bosnia: A Challenge for Dayton?" (PDF). ECMI Brief. European Centre for Minority Issues.

- Listhaug, Ola; Ramet, Sabrina P. (2013). Bosnia-Herzegovina since Dayton: civic and uncivic values'. Ravenna: Longo Editore. ISBN 978-88-8063-739-4.

- Markešić, Ivan [ed.] (2010.): Hrvati u BiH: ustavni položaj, kulturni razvoj i nacionalni identitet, Zagreb: Zagreb University School of Law, Center for democracy and law "Miko Tripalo", ISBN 978-953-270-044-2

- Neškoviċ, Radomir (2013). Nedovršena država : politički sistem Bosne i Hercegovine Sarajevo : Friedrich‐Ebert Stiftung, ISBN 9789958884207

- Soeren, Keil (2013). Multinational Federalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-409-45700-8.

- Tadić, Mato (2013.): Ustavni položaj Hrvata u BiH od Washingtonskog sporazuma do danas, Mostar: Matica hrvatska, ISBN 978-9958-9790-2-6

External links

[edit]- Croatian National Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina, official website

- Croats (Bosnia), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Self-Determination (2010)

- IDPI institute

- Bekić, Janko. "Je li Bosna i Hercegovina sada spremna za treći, hrvatski entitet?", Jutarnji list, 14. veljače 2014.

- EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION on the 2016 Commission Report on Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6 February 2017

- "Bosnia: The problem that won't go away", The Economist