Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article

Usage

[edit]The layout design for these subpages is at Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/Layout.

- Add a new Selected article to the next available subpage.

- Update "max=" to new total for its {{Random portal component}} on the main page.

Selected articles list

[edit]Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/1 Traditional African religions have shared notable relationship with other religions, cultures, traditions.

Throughout the history, they are often noted for having one of the oldest presence in the world, and also applauded for its tolerance with other religions.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/2 Traditional African religions have faced persecution from the proponents of different ideologies. Adherents of these religions have been forcefully converted to Islam and Christianity, demonized and marginalized. The atrocities include killings, waging war, destroying idols and sacred places, and other atrocious actions.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/3 'Divination (from Latin divinare "to foresee, to be inspired by a god", related to divinus, divine) is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a querent should proceed by reading signs, events, or omens, or through alleged contact with a supernatural agency.

Divination can be seen as a systematic method with which to organize what appear to be disjointed, random facets of existence such that they provide insight into a problem at hand. If a distinction is to be made between divination and fortune-telling, divination has a more formal or ritualistic element and often contains a more social character, usually in a religious context, as seen in traditional African medicine. Fortune-telling, on the other hand, is a more everyday practice for personal purposes. Particular divination methods vary by culture

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/4 There are several deities or mythological figures found in Traditional African religions. Some of these include the Yoruba figure Ogun, the Serer creator god Roog and the Igbo figure Ani.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/5 The Nommo are mythological ancestral spirits (sometimes referred to as deities) worshiped by the Dogon tribe of Mali. The word "Nommo" is derived from a Dogon word meaning "to make one drink." The Nommos are usually described as amphibious, hermaphroditic, fish-like creatures. Folk art depictions of the Nommos show creatures with humanoid upper torsos, legs/feet, and a fish-like lower torso and tail. The Nommos are also referred to as "Masters of the Water", "The Monitors", and "The Teachers". Nommo can be a proper name of an individual, or can refer to the group of spirits as a whole.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/6 African art describes the modern and historical paintings, sculptures, installations, and other visual culture from native or indigenous Africans and the African continent. The definition may also include the art of the native African, African diasporas, such as African American, Caribbean and other American art. Despite this diversity, there are some unifying artistic themes when considering the totality of the visual culture from the continent of Africa.

Traditional African religions have been extremely influential on African art forms across the continent. African art often stems from the themes of religious symbolism, functionalism and utilitarianism, and many pieces of art are created for spiritual rather than purely creative purposes. Many African cultures emphasize the importance of ancestors as intermediaries between the living, the gods, and the supreme creator, and art is seen as a way to contact these spirits of ancestors. Art may also be used to depict gods, and is valued for its functional purposes.

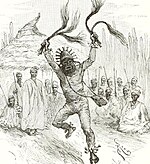

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/7 The Battle of Fandane-Thiouthioune also known as the Battle of Somb occurred on 18 July 1867. It was a religious war between the Serer people who adhered to the tenets of Serer religion and the Muslim Marabouts of 19th century Senegambia who came to convert them through jihad. Although religious, it also had a political and economic dimension to it: vendetta and empire-building. Fandane, Thiouthioune and Somb were part of the pre-colonial Serer Kingdom of Sine now part of independent Senegal. The Serer people defeated the Muslims and killed their leader.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/8

| Part of a series on Vodun related religions called |

| Voodoo |

|---|

|

Vodun (meaning spirit in the Fon and Ewe languages, pronounced [vodṹ] with a nasal high-tone u; also spelled Vodon, Vodoun, Vodou, Voudou, Voodoo, etc.) is practiced by the Fon people of Benin, and southern and central Togo; as well in Ghana, and Nigeria.

It is distinct from the various traditional African religions in the interiors of these countries and is the main source of religions with similar names found among the African diaspora in the Americas, such as Haitian Vodou; Dominican Vudú; Cuban Vodú; Brazilian Vodum (candomblé jeje and tambor de mina); Puerto Rican Vudú (Sanse); and Louisiana Voodoo.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/9 'Haitian Vodou, known commonly as Voodoo is a syncretic religion practiced chiefly in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. Practitioners are called "vodouists"

Vodouists believe in a distant and unknowable Supreme Creator, Bondye (derived from the French term Bon Dieu, meaning "good God"). According to Vodouists, Bondye does not intercede in human affairs, and thus they direct their worship toward spirits subservient to Bondye, called loa. Every loa is responsible for a particular aspect of life, with the dynamic and changing personalities of each loa reflecting the many possibilities inherent to the aspects of life over which they preside. To navigate daily life, vodouists cultivate personal relationships with the loa through the presentation of offerings, the creation of personal altars and devotional objects, and participation in elaborate ceremonies of music, dance, and spirit possession.

Vodou originated in what is now Benin and developed in the French colonial empire in the 18th century among West African peoples who were enslaved, when African religious practice was actively suppressed, and enslaved Africans were forced to convert to Christianity. Religious practices of contemporary Vodou are descended from, and closely related to, West African Vodun as practiced by the Fon and Ewe. Vodou also incorporates elements and symbolism from other African peoples including the Yoruba and Kongo; as well as Taíno religious beliefs, Roman Catholicism, and European spirituality including mysticism and other influences.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/10 Òrìṣà (original spelling in the Yoruba language), known as orichá or orixá in Latin America, are the human form of the spirits (Irunmọlẹ) sent by Olodumare, Olorun, Olofi in Yoruba traditional identity. The Irunmọlẹ are meant to guide creation and particularly humanity on how to live and succeed on Earth (Ayé). Most Òrìṣà are said to be deities previously existing in the spirit world (Òrun) as Irunmọlẹ, while others are said to be humans who are recognized as deities upon their deaths due to extraordinary feats.

Many Òrìṣà have found their way to most of the New World as a result of the Atlantic slave trade and are now expressed in practices as varied as Santería, Candomblé, Trinidad Orisha, Umbanda, and Oyotunji, among others. The concept of orisha is similar to those of deities in the traditional religions of the Bini people of Edo State in southern Nigeria, the Ewe people of Benin, Ghana, and Togo, and the Fon people of Benin.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/11

| Part of a series on |

| Serers and Serer religion |

|---|

|

The Serer creation myth is the traditional creation myth of the Serer people of Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania. Many Serers who adhere to the tenets of the Serer religion believe these narratives to be sacred. Some aspects of Serer religious and Ndut traditions are included in the narratives contained herein but are not limited to them.

The Serer people have many gods, goddesses and Pangool but one supreme deity and creator called Roog (or Koox in the Cangin languages).

Serer creation myth developed from Serer oral traditions, Serer religion, legends, cosmogonies. The specifics of the myth are also found in two main Serer sources: A nax and A leep. The former is a short narrative for a short myth or proverbial expression, whilst the later is for a more developed myth. Broadly, they are equivalent to verbs and logos respectively, especially when communicating fundamental religious education such as the supreme being and the creation of the Universe. In addition to being fixed-Serer sources, they set the structure of the myth.

The creation myth of the Serer people is intricately linked to the first trees created on Planet Earth by Roog. Earth's formation began with a swamp. The Earth was not formed until long after the creation of the first three worlds: the waters of the underworld; the air which included the higher world (i.e. the sun, the moon and the stars) and earth. Roog is the creator and fashioner of the Universe and everything in it. The creation is based on a mythical cosmic egg and the principles of chaos.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/12 The Mandé creation myth is the traditional creation myth of the Mandé peoples of southern Mali. The story begins when Mangala, the creator god, tries making a balaza seed but it failed. Then he made two eleusine seeds of different kinds, which the people of Keita call "the egg of the world in two twin parts which were to procreate". Then Mangala made three more pairs of seeds, and each pair became the four elements, the four directions, as corners in the framework of the world's creation. This he folded into a hibiscus seed. The twin pairs of seeds, which are seen as having opposite sex, are referred to as the egg or placenta of the world. This egg held an additional two pairs of twins, one male and one female, who were the archetype of people.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/13 Traditional healers of Southern Africa are practitioners of traditional African medicine in Southern Africa. They fulfill different social and political roles in the community, including divination, healing physical, emotional and spiritual illnesses, directing birth or death rituals, finding lost cattle, protecting warriors, counteracting witchcraft, and narrating the history, cosmology, and myths of their tradition. There are two main types of traditional healers within the Nguni, Sotho-Tswana, and Tsonga societies of Southern Africa: the diviner (sangoma), and the herbalist (inyanga). These healers are effectively South African shamans who are highly revered and respected in a society where illness is thought to be caused by witchcraft, pollution (contact with impure objects or occurrences) or through neglect of the ancestors. It is estimated that there are as many as 200,000 indigenous traditional healers in South Africa compared to 25,000 Western-trained doctors. Traditional healers are consulted by approximately 60% of the South African population, usually in conjunction with modern biomedical services.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/14 The Okuyi is a rite of passage practiced by several Bantu ethnic groups in different countries mainly across the west coast of Central Africa. Some of the countries where the rite is exercised include Cameroon in West Central Africa, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea. Traditionally, the rite is performed at numerous special occasions including funerals and weddings. Usually when an infant reaches four months of age or when a child becomes an adolescent, an Okuyi ritual is applied as well. Today, the Mekuyo rite is exercised by a range of ethnic peoples within the Bantu cluster. The coastal community known as Ndowe, also known as playeros, is a primary example, as peoples across Equatorial Guinea frequently perform the ritual in public. Gabon has two chief ethnic groups that exercise the Okuyi rite including the Mpongwe and Galwa from Lambaréné, Gabon.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/15 The Bantu beliefs are the system of beliefs and legends of the Bantu peoples of Africa. Although Bantu peoples account for several hundred different ethnic groups, there is a high degree of homogeneity in Bantu cultures and customs, just as in Bantu languages. The phrase "Bantu mythology" usually refers to the common, recurring themes that are found in all or most Bantu cultures.

All Bantus traditionally believe in a supreme God. The nature of God is often only vaguely defined, although he may be associated with the Sun, or the oldest of all ancestors, or have other specifications. Most names of God include the Bantu particle ng (nk), that is related to the sky; some examples are Mulungu (Yao people,Akamba of Kenya and others), Mungu (Swahili people), Kibumba (Basoga people), Imana (Banyarwanda and Barundi people), Unkulunkulu (Zulu people), Ruhanga (Nyoro and others), and Ngai (Akamba, Agikuyu and other groups). In many traditions God is supposed to live in the skies; there are also traditions that locate God on some high mountain, for example the Kirinyaga mountain - Mt. Kenya, for Kikuyu people.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/16 'Zulu traditional religion contains numerous deities commonly associated with animals or general classes of natural phenomena. Unkulunkulu is the highest God and is the creator of humanity. UNkulunkulu ("the greatest one") was created in Uhlanga, a huge swamp of reeds, before he came to Earth. Unkulunkulu is sometimes conflated with the Sky Sun god UMvelinqangi (meaning "He who was in the very beginning"), god of thunder, earthquake whose other name is Unsondo, and is the son of Unkulunkulu, the Father, and Nomkhubulwane, the Mother. The word Nomkhubulwane means the one who shapeshift into any form of an animal.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/17 The Dahomean religion was practiced by the Fon people of the Dahomey Kingdom. The kingdom existed until 1898 in what is now the country of Benin. Slaves taken from Dahomey to the Caribbean used elements of the religion to form Vodou and other religions of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/18 The Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ancient Egyptian society. It centered on the Egyptians' interaction with many deities believed to be present in, and in control of, the world. Rituals such as prayer and offerings were provided to the gods to gain their favor. Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, the rulers of Egypt, believed to possess a divine power by virtue of their position. They acted as intermediaries between their people and the gods, and were obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain Ma'at, the order of the cosmos. The state dedicated enormous resources to Egyptian rituals and to the construction of the temples.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/19 Maat or Maʽat (Egyptian mꜣꜥt /ˈmuʀʕat/) refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Maat was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet (Egyptian jzft), meaning injustice, chaos, violence or to do evil.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/20 Ifá is a Yoruba religion and system of divination. Its literary corpus is the Odu Ifá. Orunmila is identified as the Grand Priest, as he is who revealed divinity and prophecy to the world. Babalawos or Iyanifas use either the divining chain known as Opele, or the sacred palm or kola nuts called Ikin, on the wooden divination tray called Opon Ifá.

Ifá is practiced throughout the Americas, West Africa, and the Canary Islands, in the form of a complex religious system, and plays a critical role in the traditions of Santería, Candomblé, Palo, Umbanda, Vodou, and other Afro-American faiths, as well as in some traditional African religions.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/21

Afro-American religion (also known as African diasporic religions) are a number of related religions that developed in the Americas in various nations of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the southern United States. They derive from traditional African religions with some influence from other religious traditions, notably Christianity.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/22 The Mbuti mythology (or Bambuti mythology) is the mythology of the African Mbuti (also known as Bambuti) Pygmies of Congo.

The most important god of the Bambuti pantheon is Khonvoum (also Khonuum, Kmvoum, Chorum), a god of the hunt who wields a bow made from two snakes that together appear to humans as a rainbow.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/23 Khonvoum is the supreme god and creator of in the mythology of the Bambuti Pygmy people of central Africa. He is the 'great hunter', god of the hunt, and carries a bow made of two snakes which appears to mortals as a rainbow.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/24 The Nyongo society is the name of a supposed group of witches believed to exist in Cameroon and Nigeria. The legends were first written about in the 1950s by British social anthropologist, Edwin Ardener, while describing what he called the Nyongo Terror the present-day Southwest Province in Cameroon. Today the belief in this society can be found from the coast of Cameroon to the Bakossi and Beti peoples in the interior of the country. It is even found amongst the northern parts of the country with the Bamileke and Bamenda peoples.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/25 The Kirdi are the many cultures and ethnic groups who inhabit northwestern Cameroon and northeastern Nigeria. The term was applied to various peoples who had resisted Islamization.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/26

Osun-Osogbo or Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove is a sacred forest along the banks of the Osun river just outside the city of Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria.

The Osun-Osogbo Grove is among the last of the sacred forests which usually adjoined the edges of most Yoruba cities before extensive urbanization. In recognition of its global significance and its cultural value, the Sacred Grove was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.

The 1950s saw the desecration of the Osun-Osogbo Grove: shrines were neglected, priests abandoned the grove as customary responsibilities and sanctions weakened. Prohibited actions like fishing, hunting and felling of trees in the grove took place until an Austrian, Susanne Wenger, came and stopped the abuse going on in the grove.

With the encouragement of the Ataoja and the support of the local people, "Wenger formed the New Sacred Art movement to challenge land speculators, repel poachers, protect shrines and begin the long process of bringing the sacred place back to life by establishing it, again, as the sacred heart of Osogbo.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/27

The Kumpo, the Samay and the Niasse are three traditional figures in the mythology of the Diola people in the Casamance (Senegal) and in Gambia.

Multiple times in the course of the year, i.e. during the Journées culturelles, a folk festival in the village is organized. The Samay invites the people of the village to participate with the festivity.

The Kumpo is dressed with palm leaves and wears a stick on the head.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/28

| Jamaican Maroon religion | |

|---|---|

| Type | Creole |

| Classification | Afro-Jamaican |

| Theology | Obeah |

| Origin | Atlantic slave trade period Jamaica |

| Merged into | Christianity |

The traditional Jamaican Maroon religion otherwise known as Kumfu was developed by a mixing of West and Central African religious practices in Maroon communities. While the traditional religion of the Maroons was absorbed by Christianity due to conversions in Maroon communities, many old practices continued on. Some have speculated that Jamaican Maroon religion helped the development of Kumina and Convince. The religious Kromanti dance is still practiced today but not always with the full religious connotation as in the past.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/29 African divination is divination practiced by cultures of Africa.

Divination is an attempt to form, and possess, an understanding of reality in the present and additionally, to predict events and reality of a future time. Cultures of Africa to the year circa C.E. 1991 were still performing and using divination, both within the urban and the rural environments. Diviners might also fulfill the role of herbalist. Divination might be thought of as a social phenomenon, and is thought of as central to the lives of people in societies of Africa (circa 2004 at least).

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/30

The Dogon religion is the traditional religious or spiritual beliefs of the Dogon people of Mali. Dogons who adhere to the Dogon religion believe in one Supreme Creator called Amma (or Ama). They also believe in ancestral spirits known as the Nommo also referred to as "Water Spirits". Veneration of the dead is an important element in their spiritual belief. They hold ritual mask dances immediately after the death of a person and sometimes long after they have passed on to the next life. Twins, "the need for duality and the doubling of individual lives" (masculine and feminine principles) is a fundamental element in their belief system. Like other traditional African religions, balance, and reverence for nature are also key elements.

The Dogon religion is an ancient religion or spiritual system. Shannon Dorey, the Canadian author and researcher on the Dogon, their religion and symbols—believes that, the Dogon religion "is the oldest known mythology in the world." She went on: "It existed in Africa long before humans migrated to other areas of the world. When humans left Africa for other continents, they took their religion with them. Fragments of the Dogon religion thus existed all over the world making the Dogon religion the "mitochondrial religion" of the world."

The Dogon religion, cosmogony, cosmology and astronomy have been subjects of intense study by ethnologists and anthropologists since the 1930s. One of the first Western writers to document Dogon's religious beliefs was the French ethnologist Marcel Griaule—who interviewed the Dogon high priest and elder Ogotommeli back in the early 1930s. In a thirty-three days interview, Ogotommeli disclosed to Griaule the Dogon's belief system resulting in his famous book Dieu D'eau or Conversations With Ogotemmeli, originally published in 1948 as Dieu D'eau. That book by Griaule has been the go–to reference book for subsequent generations of ethnologists and anthropologists writing about Dogon religion, cosmogony, cosmology, and astronomy.

Dogon cosmology and astronomy are broad and complex. Like some of the other African groups in the Upper Niger, and other parts of the continent, they have a huge repertoire of "system of signs" which are religious in nature. This, according to Griaule and his former student Germaine Dieterlen, includes "their own systems of astronomy and calendrical measurements, methods of calculation and extensive anatomical and physiological knowledge, as well as a systematic pharmacopoeia". For this reason, Dogon cosmology and astronomy are beyond the scope of this article. This article merely gives an overview of Dogon religion and some aspects of Dogon cosmogony.

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/31 Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/31

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/32 Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/32

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/33 Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/33

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/34 Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/34

Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/35 Portal:Traditional African religions/Selected article/35