West Germany

Federal Republic of Germany Bundesrepublik Deutschland (German) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949–1990(g) | |||||||||||||||

| Motto: Gott mit uns "God with us" (1949–1962) Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit "Unity and Justice and Freedom" (since 1962) | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Ich hab mich ergeben "I have surrendered myself" (unofficial, 1949–1952)[1] | |||||||||||||||

Location of West Germany (dark green) in Europe (dark grey)  Location of West Germany (dark green) in Europe (dark grey)  Territory of West Germany Lands of pre-1937 Germany that were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union after World War II, claimed by West Germany until 1972 | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Bonn(f) | ||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Hamburg | ||||||||||||||

| Official languages | German | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | See Religion in West Germany | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic | ||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||

• 1949–1959 (first) | Theodor Heuss | ||||||||||||||

• 1984–1990 (last) | Richard von Weizsäcker(b) | ||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||||||

• 1949–1963 (first) | Konrad Adenauer | ||||||||||||||

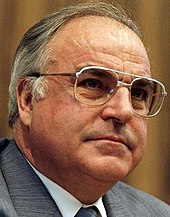

• 1982–1990 (last) | Helmut Kohlc | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Bicameralism | ||||||||||||||

| Bundesrat | |||||||||||||||

| Bundestag | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||||||

| 23 May 1949 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 May 1955 | |||||||||||||||

• Member of NATO | 9 May 1955 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 January 1957 | |||||||||||||||

• Creation of EEC | 25 March 1957 | ||||||||||||||

• Basic Treaty with the GDR | 21 December 1972 | ||||||||||||||

| 18 September 1973 | |||||||||||||||

| 12 September 1990 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 October 1990(g) | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• Total | 248,717 km2 (96,030 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1950(d) | 50,958,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1970 | 61,001,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1990 | 63,254,000 | ||||||||||||||

• Density | 254/km2 (657.9/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 1990 estimate | ||||||||||||||

• Total | ~$1.0 trillion (4th) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Deutsche Mark(e) (DM) (DEM) | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||||||||||||||

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +49 | ||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .de | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

West Germany[a] is the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany from its formation on 23 May 1949 until its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republic (German: Bonner Republik) after its capital city of Bonn.[4] During the Cold War, the western portion of Germany and the associated territory of West Berlin were parts of the Western Bloc. West Germany was formed as a political entity during the Allied occupation of Germany after World War II, established from 12 states formed in the three Allied zones of occupation held by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

At the onset of the Cold War, Europe was divided between the Western and Eastern blocs. Germany was divided into the two countries. Initially, West Germany claimed an exclusive mandate for all of Germany, representing itself as the sole democratically reorganised continuation of the 1871–1945 German Reich.[5]

Three southwestern states of West Germany merged to form Baden-Württemberg in 1952, and the Saarland joined West Germany as a state in 1957 after it had been separated as the Saar Protectorate from Allied-occupied Germany by France (the separation had been not fully legal as it had been opposed by the Soviet Union). In addition to the resulting ten states, West Berlin was considered an unofficial de facto eleventh state. While de jure not part of West Germany, for Berlin was under the control of the Allied Control Council (ACC), West Berlin politically aligned itself with West Germany and was directly or indirectly represented in its federal institutions.

The foundation for the influential position held by Germany today was laid during the economic miracle of the 1950s (Wirtschaftswunder), when West Germany rose from the enormous destruction wrought by World War II to become the world's second-largest economy. The first chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who remained in office until 1963, worked for a full alignment with the NATO rather than neutrality, and secured membership in the military alliance. Adenauer was also a proponent of agreements that developed into the present-day European Union. When the G6 was established in 1975, there was no serious debate as to whether West Germany would become a member.

Following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, symbolised by the opening of the Berlin Wall, both states took action to achieve German reunification. East Germany voted to dissolve and accede to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990. The five post-war states (Länder) were reconstituted, along with the reunited Berlin, which ended its special status and formed an additional Land. They formally joined the federal republic on 3 October 1990, raising the total number of states from ten to sixteen, and ending the division of Germany. The reunited Germany is the direct continuation of the state previously informally called West Germany and not a new state, as the process was essentially a voluntary act of accession: the Federal Republic of Germany was enlarged to include the additional six states of the German Democratic Republic. The expanded Federal Republic retained West Germany's political culture and continued its existing memberships in international organisations, as well as its Western foreign policy alignment and affiliation to Western alliances such as the United Nations, NATO, OECD, and the European Economic Community.

Naming conventions

[edit]Before reunification, Germany was divided between the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Federal Republic of Germany; commonly known as West Germany) and the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR; German Democratic Republic; commonly known as East Germany). Reunification was achieved by accession (Beitritt) of the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic of Germany, so Bundesrepublik Deutschland became the official name of reunified Germany.

In East Germany, the terms Westdeutschland (West Germany) or westdeutsche Bundesrepublik (West German Federal Republic) were preferred during the 1950s and 1960s. This changed under its constitutional amendment in 1974, when the idea of a single German nation was abandoned by East Germany. As a result, it officially considered West Germans and West Berliners as foreigners. The initialism BRD (FRG in English) began to prevail in East German usage in the early 1970s, beginning in the newspaper Neues Deutschland. Other Eastern Bloc nations soon followed suit.

In 1965, the West German Federal Minister of All-German Affairs, Erich Mende, had issued the "Directives for the Appellation of Germany", recommending avoiding the initialism BRD. On 31 May 1974, the heads of West German federal and state governments recommended always using the full name in official publications. From then on, West German sources avoided the abbreviated form, with the exception of left-leaning organizations which embraced it. In November 1979, the federal government informed the Bundestag that the West German public broadcasters ARD and ZDF had agreed to refuse to use the initialism.[6]

The ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country code of West Germany was DE (for Deutschland, Germany), which has remained the country code of Germany after reunification. ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 codes are the most widely used country codes, and the DE code is notably used as a country identifier, extending the postal code and as the Internet's country code top-level domain .de. The less widely used ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 country code of West Germany was DEU, which has remained the country code of reunified Germany. The now deleted codes for East Germany, on the other hand, were DD in ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 and DDR in ISO 3166-1 alpha-3.

The colloquial term West Germany or its equivalent was used in many languages. Westdeutschland was also a widespread colloquial form used in German-speaking countries, usually without political overtones.

History

[edit]| History of Germany |

|---|

|

On 4–11 February 1945 leaders from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union held the Yalta Conference where future arrangements regarding post-war Europe and Allied strategy against Japan in the Pacific were negotiated. They agreed that the boundaries of Germany as at 31 December 1937 would be chosen as demarcating German national territory from German-occupied territory; all German annexations after 1937 were automatically null. Subsequently, and into the 1970s, the West German state was to maintain that these 1937 boundaries continued to be 'valid in international law', although the Allies had already agreed amongst themselves that the territories east of the Oder-Neisse line must be transferred to Poland and the Soviet Union in any peace agreement. The conference agreed that post-war Germany, minus these transfers, would be divided into four occupation zones: a French Zone in the far west; a British Zone in the northwest; an American Zone in the south; and a Soviet Zone in the East. Berlin was separately divided into four zones. These divisions were not intended to dismember Germany, only to designate zones of administration.

By the subsequent Potsdam Agreement, the four Allied Powers asserted joint sovereignty over "Germany as a whole", defined as the totality of the territory within the occupation zones. Former German areas east of the rivers Oder and Neisse and outside of 'Germany as a whole' were officially separated from German sovereignty in August 1945 and transferred from Soviet military occupation to Polish and Soviet (in the case of the territory of Kaliningrad) civil administration, their Polish and Soviet status to be confirmed at a final Peace Treaty. Following wartime commitments by the Allies to the governments-in-exile of Czechoslovakia and Poland, the Potsdam Protocols also agreed to the 'orderly and humane' transfer to Germany as a whole of the ethnic German populations in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Eight million German expellees and refugees eventually settled in West Germany. Between 1946 and 1949, three of the occupation zones began to merge. First, the British and American zones were combined into the quasi-state of Bizonia. Soon afterwards, the French zone was included into Trizonia. Conversely, the Soviet zone became East Germany. At the same time, new federal states (Länder) were formed in the Allied zones; replacing the geography of pre-Nazi German states such as the Free State of Prussia and the Republic of Baden, which had derived ultimately from former independent German kingdoms and principalities.

In the dominant post-war narrative of West Germany, the Nazi regime was characterised as having been a 'criminal' state,[7] illegal and illegitimate from the outset; while the Weimar Republic was characterised as having been a 'failed' state,[8] whose inherent institutional and constitutional flaws had been exploited by Hitler in his illegal seizure of dictatorial powers. Consequently, following the death of Hitler in 1945 and the subsequent capitulation of the German Armed Forces, the national political, judicial, administrative, and constitutional instruments of both Nazi Germany and the Weimar Republic were understood as entirely defunct, such that a new West Germany could be established in a condition of constitutional nullity.[9] Nevertheless, the new West Germany asserted its fundamental continuity with the 'overall' German state that was held to have embodied the unified German people since the Frankfurt Parliament of 1848, and which from 1871 had been represented within the German Reich; albeit that this overall state had become effectively dormant long before 8 May 1945.

In 1949 with the continuation and aggravation of the Cold War (for example, the Berlin Airlift of 1948–49), the two German states that had originated in the Western Allied and the Soviet Zones respectively became known internationally as West Germany and East Germany. Commonly known in English as East Germany, the former Soviet occupation zone in Germany, eventually became the German Democratic Republic or GDR. In 1990 West Germany and East Germany jointly signed the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (also known as the "Two-plus-Four Agreement"); by which transitional status of Germany following World War II was definitively ended and the Four Allied powers relinquished their joint residual sovereign authority for Germany as a whole including the area of West Berlin which had officially remained under Allied occupation for the purposes of international and GDR law (a status that the Western countries applied to Berlin as a whole despite the Soviets declaring the end of occupation of East Berlin unilaterally many decades before). The Two-plus-Four Agreement also saw the two parts of Germany confirm their post-war external boundaries as final and irreversible (including the 1945 transfer of former German lands east of the Oder–Neisse line), and the Allied Powers confirmed their consent to German Reunification. From 3 October 1990, after the reformation of the GDR's Länder, the East German states and East Berlin joined the Federal Republic.

NATO membership

[edit]

With territories and frontiers that coincided largely with the ones of old Middle Ages East Francia and the 19th-century Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine, the Federal Republic of Germany was founded on 23 May 1949 under the terms of the Bonn–Paris conventions, whereby it obtained "the full authority of a sovereign state" on 5 May 1955 (although "full sovereignty" was not obtained until the Two Plus Four Agreement in 1990).[b] The former occupying Western troops remained on the ground, now as part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which West Germany joined on 9 May 1955, promising to rearm itself soon.[11]

West Germany became a focus of the Cold War with its juxtaposition to East Germany, a member of the subsequently founded Warsaw Pact. The former capital, Berlin, had been divided into four sectors, with the Western Allies joining their sectors to form West Berlin, while the Soviets held East Berlin. West Berlin was completely surrounded by East German territory and had suffered a Soviet blockade in 1948–49, which was overcome by the Berlin airlift.

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 led to U.S. calls to rearm West Germany to help defend Western Europe from the perceived Soviet threat. Germany's partners in the European Coal and Steel Community proposed to establish a European Defence Community (EDC), with an integrated army, navy and air force, composed of the armed forces of its member states. The West German military would be subject to complete EDC control, but the other EDC member states (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) would cooperate in the EDC while maintaining independent control of their own armed forces.

Though the EDC treaty was signed (May 1952), it never entered into force. France's Gaullists rejected it on the grounds that it threatened national sovereignty, and when the French National Assembly refused to ratify it (August 1954), the treaty died. The French Gaullists and communists had killed the French government's proposal. Then other means had to be found to allow West German rearmament. In response, at the London and Paris Conferences, the Brussels Treaty was modified to include West Germany, and to form the Western European Union (WEU). West Germany was to be permitted to rearm (an idea many Germans rejected), and have full sovereign control of its military, called the Bundeswehr. The WEU, however, would regulate the size of the armed forces permitted to each of its member states. Also, the German constitution prohibited any military action, except in the case of an external attack against Germany or its allies (Bündnisfall). Also, Germans could reject military service on grounds of conscience, and serve for civil purposes instead.[12]

The three Western Allies retained occupation powers in Berlin and certain responsibilities for Germany as a whole. Under the new arrangements, the Allies stationed troops within West Germany for NATO defense, pursuant to stationing and status-of-forces agreements. With the exception of 55,000 French troops, Allied forces were under NATO's joint defense command. (France withdrew from the collective military command structure of NATO in 1966.)

Reforms during the 1960s

[edit]Konrad Adenauer was 73 years old when he became chancellor in 1949, and for this reason he was initially reckoned as a caretaker. However, he ruled for 14 years. The grand statesman of German postwar politics had to be dragged—almost literally—out of office in 1963.[13]

In October 1962 the weekly news magazine Der Spiegel published an analysis of the West German military defence. The conclusion was that there were several weaknesses in the system. Ten days after publication, the offices of Der Spiegel in Hamburg were raided by the police and quantities of documents were seized. Chancellor Adenauer proclaimed in the Bundestag that the article was tantamount to high treason and that the authors would be prosecuted. The editor/owner of the magazine, Rudolf Augstein spent some time in jail before the public outcry over the breaking of laws on freedom of the press became too loud to be ignored. The FDP members of Adenauer's cabinet resigned from the government, demanding the resignation of Franz Josef Strauss, Defence Minister, who had decidedly overstepped his competence during the crisis. Adenauer was still wounded by his brief run for president, and this episode damaged his reputation even further. He announced that he would step down in the fall of 1963. His successor was to be Ludwig Erhard.[14]

In the early 1960s, the rate of economic growth slowed down significantly. In 1962 growth rate was 4.7% and the following year, 2.0%. After a brief recovery, the growth rate slowed again into a recession, with no growth in 1967.

A new coalition was formed to deal with this problem. Erhard stepped down in 1966 and was succeeded by Kurt Georg Kiesinger. He led a grand coalition between West Germany's two largest parties, the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). This was important for the introduction of new emergency acts: the grand coalition gave the ruling parties the two-thirds majority of votes required for their ratification. These controversial acts allowed basic constitutional rights such as freedom of movement to be limited in case of a state of emergency.

During the time leading up to the passing of the laws, there was fierce opposition to them, above all by the Free Democratic Party, the rising West German student movement, a group calling itself Notstand der Demokratie ("Democracy in Crisis") and members of the Campaign against Nuclear Armament. A key event in the development of open democratic debate occurred in 1967, when the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, visited West Berlin. Several thousand demonstrators gathered outside the Opera House where he was to attend a special performance. Supporters of the Shah (later known as Jubelperser), armed with staves and bricks attacked the protesters while the police stood by and watched. A demonstration in the centre was being forcibly dispersed when a bystander named Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head and killed by a plainclothes policeman. (It has now been established that the policeman, Kurras, was a paid spy of the East German security forces.) Protest demonstrations continued, and calls for more active opposition by some groups of students were made, which was declared by the press, especially the tabloid Bild-Zeitung newspaper, as a massive disruption to life in Berlin, in a massive campaign against the protesters. Protests against the US intervention in Vietnam, mingled with anger over the vigour with which demonstrations were repressed led to mounting militance among the students at the universities in Berlin. One of the most prominent campaigners was a young man from East Germany called Rudi Dutschke who also criticised the forms of capitalism that were to be seen in West Berlin. Just before Easter 1968, a young man tried to kill Dutschke as he bicycled to the student union, seriously injuring him. All over West Germany, thousands demonstrated against the Springer newspapers which were seen as the prime cause of the violence against students. Trucks carrying newspapers were set on fire and windows in office buildings broken.[15]

In the wakes of these demonstrations, in which the question of America's role in Vietnam began to play a bigger role, came a desire among the students to find out more about the role of the parent-generation in the Nazi era. The proceedings of the War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg had been widely publicised in Germany but until a new generation of teachers, educated with the findings of historical studies, could begin to reveal the truth about the war and the crimes committed in the name of the German people, one courageous attorney, Fritz Bauer patiently gathered evidence on the guards of the Auschwitz concentration camp and about twenty were put on trial in Frankfurt in 1963. Daily newspaper reports and visits by school classes to the proceedings revealed to the German public the nature of the concentration camp system and it became evident that the Shoah was of vastly greater dimensions than the German population had believed. (The term "Holocaust" for the systematic mass-murder of Jews first came into use in 1979, when a 1978 American mini-series with that name was shown on West German television.) The processes set in motion by the Auschwitz trial reverberated decades later.

The calling in question of the actions and policies of government led to a new climate of debate. The issues of emancipation, colonialism, environmentalism and grass roots democracy were discussed at all levels of society. In 1979 the environmental party, the Greens, reached the 5% limit required to obtain parliamentary seats in the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen provincial election. Also of great significance was the steady growth of a feminist movement in which women demonstrated for equal rights. Until 1977, a married woman had to have the permission of her husband if she wanted to take on a job or open a bank account.[16] Further reforms in 1979 to parental rights law gave equal legal rights to the mother and the father, abolishing the legal authority of the father.[17] Parallel to this, a gay movement began to grow in the larger cities, especially in West Berlin, where homosexuality had been widely accepted during the twenties in the Weimar Republic.

Anger over the treatment of demonstrators following the death of Benno Ohnesorg and the attack on Rudi Dutschke, coupled with growing frustration over the lack of success in achieving their aims led to growing militance among students and their supporters. In May 1968, three young people set fire to two department stores in Frankfurt; they were brought to trial and made very clear to the court that they regarded their action as a legitimate act in what they described as the "struggle against imperialism".[15] The student movement began to split into different factions, ranging from the unattached liberals to the Maoists and supporters of direct action in every form—the anarchists. Several groups set as their objective the aim of radicalising the industrial workers and taking an example from activities in Italy of the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse), many students went to work in the factories, but with little or no success. The most notorious of the underground groups was the Red Army Faction which began by making bank raids to finance their activities and eventually went underground having killed a number of policemen, several bystanders and eventually two prominent West Germans, whom they had taken captive in order to force the release of prisoners sympathetic to their ideas. In the 1990s attacks were still being committed under the name "RAF". The last action took place in 1993 and the group announced it was giving up its activities in 1998. Evidence that the groups had been infiltrated by German Intelligence undercover agents has since emerged, partly through the insistence of the son of one of their prominent victims, the State Counsel Siegfried Buback.[18]

Willy Brandt

[edit]In October 1969 Willy Brandt became chancellor. He maintained West Germany's close alignment with the United States and focused on strengthening European integration in western Europe, while launching the new policy of Ostpolitik aimed at improving relations with Eastern Europe. Brandt was controversial on both the right wing, for his Ostpolitik, and on the left wing, for his support of American policies, including the Vietnam War, and right-wing authoritarian regimes. The Brandt Report became a recognised measure for describing the general North-South divide in world economics and politics between an affluent North and a poor South. Brandt was also known for his fierce anti-communist policies at the domestic level, culminating in the Radikalenerlass (Anti-Radical Decree) in 1972. In 1970, while visiting a memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising crushed by the Germans, Brandt unexpectedly knelt and meditated in silence, a moment remembered as the Kniefall von Warschau.

Brandt resigned as chancellor in 1974, after Günter Guillaume, one of his closest aides, was exposed as an agent of the Stasi, the East German secret service.

Helmut Schmidt

[edit]Finance Minister Helmut Schmidt (SPD) formed a coalition and he served as Chancellor from 1974 to 1982. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, a leading FDP official, became Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister. Schmidt, a strong supporter of the European Community (EC) and the Atlantic alliance, emphasized his commitment to "the political unification of Europe in partnership with the USA".[19] Mounting external problems forced Schmidt to concentrate on foreign policy and limited the domestic reforms that he could carry out. The USSR upgraded its intermediate-range missiles, which Schmidt complained was an unacceptable threat to the balance of nuclear power, because it increased the likelihood of political coercion and required a western response. NATO responded in the form of its twin-track policy. The domestic reverberations were serious inside the SPD, and undermined its coalition with the FDP.[20] One of his major successes, in collaboration with French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, was the launching of the European Monetary System (EMS) in April 1978.[21]

Helmut Kohl

[edit]In October 1982 the SPD–FDP coalition fell apart when the FDP joined forces with the CDU/CSU to elect CDU Chairman Helmut Kohl as Chancellor in a constructive vote of no confidence. Following national elections in March 1983, Kohl emerged in firm control of both the government and the CDU. The CDU/CSU fell just short of an absolute majority, due to the entry into the Bundestag of the Greens, who received 5.6% of the vote.

In January 1987 the Kohl–Genscher government was returned to office, but the FDP and the Greens gained at the expense of the larger parties. Kohl's CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, slipped from 48.8% of the vote in 1983 to 44.3%. The SPD fell to 37%; long-time SPD Chairman Brandt subsequently resigned in April 1987 and was succeeded by Hans-Jochen Vogel. The FDP's share rose from 7% to 9.1%, its best showing since 1980. The Greens' share rose to 8.3% from their 1983 share of 5.6%.

Reunification

[edit]With the collapse of eastern bloc in 1989, symbolised by the opening of the Berlin Wall, there was a rapid move towards German reunification; and a final settlement of the post-war special status of Germany. Following democratic elections, East Germany declared its accession to the Federal Republic subject to the terms of the Unification Treaty between the two states; and then both West Germany and East Germany radically amended their respective constitutions in accordance with that Treaty's provisions. East Germany then dissolved itself, and its five post-war states (Länder) were reconstituted, along with the reunited Berlin which ended its special status and formed an additional Land. They formally joined the Federal Republic on 3 October 1990, raising the number of states from 10 to 16, ending the division of Germany. The expanded Federal Republic retained West Germany's political culture and continued its existing memberships in international organisations, as well as its Western foreign policy alignment and affiliation to Western alliances like NATO and the European Union.

The official German reunification ceremony on 3 October 1990 was held at the Reichstag building, including Chancellor Helmut Kohl, President Richard von Weizsäcker, former Chancellor Willy Brandt and many others. One day later, the parliament of the united Germany would assemble in an act of symbolism in the Reichstag building.

However, at that time, the role of Berlin had not yet been decided upon. Only after a fierce debate, considered by many as one of the most memorable sessions of parliament, the Bundestag concluded on 20 June 1991, with quite a slim majority, that both government and parliament should move to Berlin from Bonn.

Government and politics

[edit]Political life in West Germany was remarkably stable and orderly. The Adenauer era (1949–63) was followed by a brief period under Ludwig Erhard (1963–66) who, in turn, was replaced by Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1966–69). All governments between 1949 and 1966 were formed by the united caucus of the Christian-Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU), either alone or in coalition with the smaller Free Democratic Party (FDP) or other right-wing parties.

Kiesinger's 1966–69 "Grand Coalition" was between West Germany's two largest parties, the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). This was important for the introduction of new emergency acts—the Grand Coalition gave the ruling parties the two-thirds majority of votes required to see them in. These controversial acts allowed basic constitutional rights such as freedom of movement to be limited in case of a state of emergency.

Leading up to the passing of the laws, there was fierce opposition to them, above all by the FDP, the rising German student movement, a group calling itself Notstand der Demokratie ("Democracy in a State of Emergency") and the labour unions. Demonstrations and protests grew in number, and in 1967 the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head by a policeman. The press, especially the tabloid Bild-Zeitung newspaper, launched a campaign against the protesters.

By 1968, a stronger desire to confront the Nazi past had come into being. In the 1970s environmentalism and anti-nationalism became fundamental values among left-wing Germans. As a result, in 1979 the Greens were able to reach the 5% minimum required to obtain parliamentary seats in the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen state election, and with the foundation of the national party in 1980 developed into one of the most politically successful green movements in the world.

Another result of the unrest in the 1960s was the founding of the Red Army Faction (RAF). The RAF was active from 1968, carrying out a succession of terrorist attacks in West Germany during the 1970s. Even in the 1990s, attacks were still being committed under the name RAF. The last action took place in 1993, and in 1998 the group announced it was ceasing activities.

In the 1969 election, the SPD gained enough votes to form a coalition government with the FDP. SPD leader and Chancellor Willy Brandt remained head of government until May 1974, when he resigned after the Guillaume affair, in which a senior member of his staff was uncovered as a spy for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi. However, the affair is widely considered to have been merely a trigger for Brandt's resignation, not a fundamental cause. Instead, Brandt, dogged by scandal relating to alcohol and depression[22][23] as well as the economic fallout of the 1973 oil crisis, almost seems simply to have had enough. As Brandt himself later said, "I was exhausted, for reasons which had nothing to do with the process going on at the time".[24]

Finance Minister Helmut Schmidt (SPD) then formed a government, continuing the SPD–FDP coalition. He served as Chancellor from 1974 to 1982. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, a leading FDP official, was Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister in the same years. Schmidt, a strong supporter of the European Community (EC) and the Atlantic alliance, emphasized his commitment to "the political unification of Europe in partnership with the USA".

The goals of SPD and FDP however drifted apart in the late 1970s and early 1980s. On 1 October 1982 the FDP joined forces with the CDU/CSU to elect CDU Chairman Helmut Kohl as Chancellor in a constructive vote of no confidence. Following national elections in March 1983, Kohl emerged in firm control of both the government and the CDU. The CDU/CSU fell just short of an absolute majority, because of the entry into the Bundestag of the Greens, who received 5.6% of the vote.

In January 1987 the Kohl–Genscher government was returned to office, but the FDP and the Greens gained at the expense of the larger parties. The Social Democrats concluded that not only were the Greens unlikely to form a coalition, but also that such a coalition would be far from a majority. Neither condition changed until 1998.

Denazification

[edit]Denazification was an Allied initiative to rid German politics, judiciary, society, culture, press and economy of Nazi ideology and personnel following the Second World War. It was carried out by removing those who had been Nazi Party or SS members from positions of power and influence, by disbanding the organizations associated with Nazism, and by trying prominent Nazis for war crimes.[25] The program was hugely unpopular in West Germany and was opposed by the new government of Konrad Adenauer.[26] In 1951, several laws were passed granting amnesties and ending denazification. As a result, many people with a former Nazi past ended up again in the political apparatus of West Germany.[27]

Between 1951 and 1953, there was even an effort by a clandestine group of former Nazi functionaries, known as the Naumann Circle, to infiltrate the Free Democratic Party (FDP) in order to lay the groundwork for an eventual return to power. Although this effort was exposed and disrupted, many former Nazis still attained positions of power and influence in the political system.[28] West German President (1974–1979) Walter Scheel and Chancellor (1966–1969) Kurt Georg Kiesinger were both former members of the Nazi Party. Konrad Adenauer's State Secretary Hans Globke had played a major role in drafting the antisemitic Nuremberg Race Laws in Nazi Germany.[29] In 1957, 77% of the West German Ministry of Justice's senior officials were former Nazi Party members.[30]

Geographical distribution of government

[edit]In West Germany, most of the political agencies and buildings were located in Bonn, while the German Stock Market was located in Frankfurt which became the economic center. The judicial branch of both the German Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) and the highest Court of Appeals, were located in Karlsruhe.

The West German government was known to be much more decentralised than its state socialist East German counterpart, the former being a federal state and the latter a unitary one. Whilst East Germany was divided into 15 administrative districts (Bezirke), which were merely local branches of the national government, West Germany was divided into states (Länder) with independently elected state parliaments and control of the Bundesrat, the second legislative chamber of the Federal Government.

Foreign relations

[edit]Position towards East Germany

[edit]

The official position of West Germany concerning East Germany at the outset was that the West German government was the only democratically elected, and therefore the only legitimate, representative of the German people. According to the Hallstein Doctrine, any country (with the exception of the USSR) that recognised the authorities of the German Democratic Republic would not have diplomatic relations with West Germany.

In the early 1970s, Willy Brandt's policy of "Neue Ostpolitik" led to a form of mutual recognition between East and West Germany. The Treaty of Moscow (August 1970), the Treaty of Warsaw (December 1970), the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (September 1971), the Transit Agreement (May 1972), and the Basic Treaty (December 1972) helped to normalise relations between East and West Germany and led to both German states joining the United Nations. The Hallstein Doctrine was relinquished, and West Germany ceased to claim an exclusive mandate for Germany as a whole.

Following the Ostpolitik, the West German view was that East Germany was a de facto government within a single German nation and a de jure state organisation of parts of Germany outside the Federal Republic. The Federal Republic continued to maintain that it could not within its own structures recognise the GDR de jure as a sovereign state under international law; while at the same time acknowledging that, within the structures of international law, the GDR was an independent sovereign state. By distinction, West Germany then viewed itself as being within its own boundaries, not only the de facto and de jure government, but also the sole de jure legitimate representative of a dormant "Germany as whole".[31] The two Germanies relinquished any claim to represent the other internationally, which they acknowledged as necessarily implying a mutual recognition of each other as both capable of representing their own populations de jure in participating in international bodies and agreements, such as the United Nations and the Helsinki Final Act.

This assessment of the Basic Treaty was confirmed in a decision of the Federal Constitutional Court in 1973;[32]

- "... the German Democratic Republic is in the international-law sense a State and as such a subject of international law. This finding is independent of recognition in international law of the German Democratic Republic by the Federal Republic of Germany. Such recognition has not only never been formally pronounced by the Federal Republic of Germany but on the contrary repeatedly explicitly rejected. If the conduct of the Federal Republic of Germany towards the German Democratic Republic is assessed in the light of its détente policy, in particular the conclusion of the Treaty as de facto recognition, then it can only be understood as de facto recognition of a special kind. The special feature of this Treaty is that while it is a bilateral Treaty between two States, to which the rules of international law apply and which like any other international treaty possesses validity, it is between two States that are parts of a still existing, albeit incapable of action as not being reorganized, comprehensive State of the Whole of Germany with a single body politic."[33]

The West German Constitution (Grundgesetz, "Basic Law") provided two articles for the unification with other parts of Germany:

- Article 23 provided the possibility for other parts of Germany to join the Federal Republic (under the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany).

- Article 146 provided the possibility for unification of all parts of Germany under a new constitution.

After the peaceful revolution of 1989 in East Germany, the Volkskammer of the GDR on 23 August 1990 declared the accession of East Germany to the Federal Republic under Article 23 of the Basic Law and thus initiated the process of reunification, to come into effect on 3 October 1990. Nevertheless, the act of reunification itself (with its many specific terms and conditions; including fundamental amendments to the West German Basic Law) was achieved constitutionally by the subsequent Unification Treaty of 31 August 1990; that is through a binding agreement between the former GDR and the Federal Republic now recognising each another as separate sovereign states in international law.[34] This treaty was then voted into effect on 20 September 1990 by both the Volkskammer and the Bundestag by the constitutionally required two-thirds majorities; effecting on the one hand, the extinction of the GDR and the re-establishment of Länder on the territory of East Germany; and on the other, the agreed amendments to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic. Amongst these amendments was the repeal of the very Article 23 in respect of which the GDR had nominally declared its postdated accession to the Federal Republic.

The two German states entered into a currency and customs union in July 1990, and on 3 October 1990, the German Democratic Republic dissolved and the re-established five East German Länder (as well as a unified Berlin) joined the Federal Republic of Germany, bringing an end to the East–West divide.

Economy

[edit]Economic miracle

[edit]The West German Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle", coined by The Times) began in 1950. This improvement was sustained by the currency reform of 1948 which replaced the Reichsmark with the Deutsche Mark and halted rampant inflation. The Allied dismantling of the West German coal and steel industry finally ended in 1950.

As demand for consumer goods increased after World War II, the resulting shortage helped overcome lingering resistance to the purchase of German products. At the time Germany had a large pool of skilled and cheap labour, partly as a result of the flight and expulsion of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe, which affected up to 16.5 million Germans. This helped Germany to more than double the value of its exports during the war. Apart from these factors, hard work and long hours at full capacity among the population and in the late 1950s and 1960s extra labour supplied by thousands of Gastarbeiter ("guest workers") provided a vital base for the economic upturn. This would have implications later on for successive German governments as they tried to assimilate this group of workers.[35]

With the dropping of Allied reparations, the freeing of German intellectual property and the impact of the Marshall Plan stimulus, West Germany developed one of the strongest economies in the world, almost as strong as before the Second World War. The East German economy showed a certain growth, but not as much as in West Germany, partly because of continued reparations to the USSR.[36]

In 1952, West Germany became part of the European Coal and Steel Community, which would later evolve into the European Union. On 5 May 1955 West Germany was declared to have the "authority of a sovereign state".[b] The British, French and U.S. militaries remained in the country, just as the Soviet Army remained in East Germany. Four days after obtaining the "authority of a sovereign state" in 1955, West Germany joined NATO. The UK and the USA retained an especially strong presence in West Germany, acting as a deterrent in case of a Soviet invasion. In 1976 West Germany became one of the founding nations of the Group of Six (G6). In 1973, West Germany—home to roughly 1.26% of the world's population—featured the world's fourth largest GDP of 944 billion (5.9% of the world total). In 1987 the FRG held a 7.4% share of total world production.

Demographics

[edit]Population and vital statistics

[edit]Total population of West Germany from 1950 to 1990, as collected by the Statistisches Bundesamt.[3]

| Average population (x 1000)[38] | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 732 998 | 588 331 | 144 667 | 15.9 | 12.7 | 3.2 | 1.89 | |

| 1947 | 781 421 | 574 628 | 206 793 | 16.6 | 12.2 | 4.4 | 2.01 | |

| 1948 | 806 074 | 515 092 | 290 982 | 16.7 | 10.6 | 6.0 | 2.07 | |

| 1949 | 832 803 | 517 194 | 315 609 | 16.9 | 10.5 | 6.4 | 2.14 | |

| 1950 | 50 958 | 812 835 | 528 747 | 284 088 | 16.3 | 10.6 | 5.7 | 2.10 |

| 1951 | 51 435 | 795 608 | 543 897 | 251 711 | 15.7 | 10.8 | 4.9 | 2.06 |

| 1952 | 51 864 | 799 080 | 545 963 | 253 117 | 15.7 | 10.7 | 5.0 | 2.08 |

| 1953 | 52 454 | 796 096 | 578 027 | 218 069 | 15.5 | 11.3 | 4.2 | 2.07 |

| 1954 | 52 943 | 816 028 | 555 459 | 260 569 | 15.7 | 10.7 | 5.0 | 2.12 |

| 1955 | 53 518 | 820 128 | 581 872 | 238 256 | 15.7 | 11.1 | 4.6 | 2.11 |

| 1956 | 53 340 | 855 887 | 599 413 | 256 474 | 16.1 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 2.19 |

| 1957 | 54 064 | 892 228 | 615 016 | 277 212 | 16.6 | 11.5 | 5.2 | 2.28 |

| 1958 | 54 719 | 904 465 | 597 305 | 307 160 | 16.7 | 11.0 | 5.7 | 2.29 |

| 1959 | 55 257 | 951 942 | 605 504 | 346 438 | 17.3 | 11.0 | 6.3 | 2.34 |

| 1960 | 55 958 | 968 629 | 642 962 | 325 667 | 17.4 | 11.6 | 5.9 | 2.37 |

| 1961 | 56 589 | 1 012 687 | 627 561 | 385 126 | 18.0 | 11.2 | 6.9 | 2.47 |

| 1962 | 57 247 | 1 018 552 | 644 819 | 373 733 | 17.9 | 11.3 | 6.6 | 2.45 |

| 1963 | 57 865 | 1 054 123 | 673 069 | 381 054 | 18.4 | 11.7 | 6.7 | 2.52 |

| 1964 | 58 587 | 1 065 437 | 644 128 | 421 309 | 18.3 | 11.1 | 7.2 | 2.55 |

| 1965 | 59 297 | 1 044 328 | 677 628 | 366 700 | 17.8 | 11.6 | 6.3 | 2.51 |

| 1966 | 59 793 | 1 050 345 | 686 321 | 364 024 | 17.8 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 2.54 |

| 1967 | 59 948 | 1 019 459 | 687 349 | 332 110 | 17.2 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 2.54 |

| 1968 | 60 463 | 969 825 | 734 048 | 235 777 | 16.3 | 12.3 | 4.0 | 2.39 |

| 1969 | 61 195 | 903 456 | 744 360 | 159 096 | 15.0 | 12.4 | 2.6 | 2.20 |

| 1970 | 61 001 | 810 808 | 734 843 | 75 965 | 13.4 | 12.1 | 1.3 | 1.99 |

| 1971 | 61 503 | 778 526 | 730 670 | 47 856 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 0.8 | 1.92 |

| 1972 | 61 809 | 701 214 | 731 264 | −30 050 | 11.3 | 11.8 | −0.5 | 1.72 |

| 1973 | 62 101 | 635 663 | 731 028 | −95 395 | 10.3 | 11.8 | −1.5 | 1.54 |

| 1974 | 61 991 | 626 373 | 727 511 | −101 138 | 10.1 | 11.7 | −1.6 | 1.51 |

| 1975 | 61 645 | 600 512 | 749 260 | −148 748 | 9.7 | 12.1 | −2.4 | 1.45 |

| 1976 | 61 442 | 602 851 | 733 140 | −130 289 | 9.8 | 11.9 | −2.1 | 1.46 |

| 1977 | 61 353 | 582 344 | 704 922 | −122 578 | 9.5 | 11.5 | −2.0 | 1.40 |

| 1978 | 61 322 | 576 468 | 723 218 | −146 750 | 9.4 | 11.8 | −2.4 | 1.38 |

| 1979 | 61 439 | 581 984 | 711 732 | −129 748 | 9.5 | 11.6 | −2.1 | 1.39 |

| 1980 | 61 658 | 620 657 | 714 117 | −93 460 | 10.1 | 11.6 | −1.5 | 1.44 |

| 1981 | 61 713 | 624 557 | 722 192 | −97 635 | 10.1 | 11.7 | −1.6 | 1.43 |

| 1982 | 61 546 | 621 173 | 715 857 | −94 684 | 10.1 | 11.6 | −1.5 | 1.41 |

| 1983 | 61 307 | 594 177 | 718 337 | −124 160 | 9.7 | 11.7 | −2.0 | 1.33 |

| 1984 | 61 049 | 584 157 | 696 118 | −111 961 | 9.5 | 11.4 | −1.9 | 1.29 |

| 1985 | 61 020 | 586 155 | 704 296 | −118 141 | 9.6 | 11.6 | −2.0 | 1.28 |

| 1986 | 61 140 | 625 963 | 701 890 | −118 141 | 10.3 | 11.5 | −1.2 | 1.34 |

| 1987 | 61 238 | 642 010 | 687 419 | −45 409 | 10.5 | 11.3 | −0.8 | 1.37 |

| 1988 | 61 715 | 677 259 | 687 516 | −10 257 | 11.0 | 11.2 | −0.2 | 1.41 |

| 1989 | 62 679 | 681 537 | 697 730 | −16 193 | 11.0 | 11.2 | −0.2 | 1.39 |

| 1990 | 63 726 | 727 199 | 713 335 | 13 864 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 0.2 | 1.45 |

Religion

[edit]Religious affiliation in West Germany decreased from the 1960s onward.[39] Religious affiliation declined faster among Protestants than among Catholics, causing the Roman Catholic Church to overtake the EKD as the largest denomination in the country during the 1970s.

| Year | EKD Protestant [%] | Roman Catholic [%] | Muslim [%] | None/other [%][40][41] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 50.6 | 45.8 | – | 3.6 |

| 1961 | 51.1 | 45.5 | – | 3.5 |

| 1970 | 49.0 | 44.6 | 1.3 | 3.9 |

| 1975 | 44.1 | 43.8 | – | – |

| 1980 | 42.3 | 43.3 | – | – |

| 1987 | 41.6 | 42.9 | 2.7 | 11.4 |

Culture

[edit]In many aspects, German culture continued in spite of the dictatorship and wartime. Old and new forms coexisted next to each other, and the American influence, already strong in the 1920s, grew.[42]

Literary scene

[edit]Besides the interest in the older generation of writers, new authors emerged on the background of the experiences of war and after war period. Wolfgang Borchert, a former soldier who died young in 1947, is one of the best known representatives of the Trümmerliteratur. Heinrich Böll is considered an observer of the young Federal Republic from the 1950s to the 1970s, and caused some political controversies because of his increasingly critical view on society.[citation needed] The Frankfurt Book Fair (and its Peace Prize of the German Book Trade) soon developed into a regarded institution. Exemplary for West Germany's literature are – among others – Siegfried Lenz (with The German Lesson) and Günter Grass (with The Tin Drum and The Flounder).

Sport

[edit]

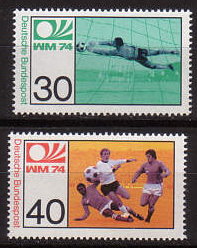

In the 20th century, association football became the largest sport in Germany. The Germany national football team, established in 1900, continued its tradition based in the Federal Republic of Germany, winning the 1954 FIFA World Cup in a stunning upset dubbed the miracle of Bern. Earlier, the German team was not considered part of the international top. The 1974 FIFA World Cup was held in West German cities and West Berlin. After having been beaten by their East German counterparts in the first round, the team of the German Football Association won the cup again, defeating the Netherlands 2–1 in the final. With the process of unification in full swing in the summer of 1990, the Germans won a third World Cup, with players that had been capped for East Germany not yet permitted to contribute. European championships have been won too, in 1972 and 1980.[43][44]

After both Olympic Games of 1936 had been held in Germany, Munich was selected to host the 1972 Summer Olympics. These were also the first summer games in which the East Germans showed up with the separate flag and anthem of the GDR. Since the 1950s, Germany at the Olympics had been represented by a united team led by the pre-war German NOC officials as the IOC had denied East German demands for a separate team. At the 1956 Summer Olympics, the Olympic teams of West Germany, East Germany, and Saarland were merged to represent Germany together. Four years earlier Saarland had attended as separate teams while East Germany had not attended. After 1956, 1962, and 1964; East Germany competed in the Summer Olympics as a separate member of the IOC.

The 800-page Doping in Germany from 1950 to today study details how the West German government helped fund a wide-scale doping programme.[45][46] West Germany encouraged and covered up a culture of doping across many sports for decades.[47][48]

As in 1957, when the Saarland acceded, East German sport organisations ceased to exist in late 1990 as their subdivisions and their members joined their Western counterparts. Thus, the present German organisations and teams in football, Olympics and elsewhere are identical to those that had been informally called "West German" before 1991. The only differences were a larger membership and a different name used by some foreigners. These organisations and teams in turn mostly continued the traditions of those that represented Germany before the Second World War, and even the First World War, thus providing a century-old continuity despite political changes. On the other hand, the separate East German teams and organisations were founded in the 1950s; they were an episode lasting less than four decades, yet quite successful in that time.[citation needed]

West Germany played 43 matches at the European Championships, more than any other national team.[49]

See also

[edit]- History of Germany (1945–1990)

- Inner German relations

- Economic history of the German reunification

- Petersberg Agreement

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ German: Westdeutschland, [ˈvɛstˌdɔɪ̯t͡ʃlant] ; officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; German: Bundesrepublik Deutschland [ˈbʊndəsʁepuˌbliːk ˈdɔʏtʃlant] , BRD)

- ^ a b Detlef Junker of the Heidelberg University states "In the October 23, 1954, Paris Agreements, Adenauer pushed through the following laconic wording: 'The Federal Republic shall accordingly [after termination of the occupation regime] have the full authority of a sovereign state over its internal and external affairs.' If this was intended as a statement of fact, it must be conceded that it was partly fiction and, if interpreted as wishful thinking, it was a promise that went unfulfilled until 1990. The Allies maintained their rights and responsibilities regarding Berlin and Germany as a whole, particularly the responsibility for future reunification and a future peace treaty".[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Applegate, Celia (ed.). Music and German National Identity. University of Chicago Press. 2002. p. 263.

- ^ "Fehler". bundesregierung.de. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011.

- ^ a b Bevölkerungsstand Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Bonn Republic — West German democracy, 1945–1990, Anthony James Nicholls, Longman, 1997

- ^ "Germany". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ See in general: Stefan Schmidt, "Die Diskussion um den Gebrauch der Abkürzung «BRD»", in: Aktueller Begriff, Deutscher Bundestag – Wissenschaftliche Dienste (ed.), No. 71/09 (4 September 2009)

- ^ Collings (2015), p. xxiv.

- ^ Collings (2015), p. xv.

- ^ Jutta Limbach, How a constitution can safeguard democracy:The German Experience (PDF), Goethe-Institut, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Detlef Junker (editor), Translated by Sally E. Robertson, The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, A Handbook Volume 1, 1945–1968 Series: Publications of the German Historical Institutes ISBN 0-511-19218-5. See Section "The Presence of the Past" paragraph 9.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1961). "NATO and Adenauer's Germany: Uneasy Partnership". International Organization. 15 (4): 618–629. doi:10.1017/S0020818300010663. S2CID 155025137.

- ^ John A. Reed Jr, Germany and NATO (National Defense University, 1987) Online.

- ^ William Glenn Gray, "Adenauer, Erhard, and the Uses of Prosperity." German Politics and Society 25.2 (2007): 86–103.

- ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski, Ludwig Erhard: A Biography (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2005) p 179. Online Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Wolfgang Kraushaar, Frankfurter Schule und Studentenbewegung, vol. 2 Dokumente, Rogner und Bernhard, 1998 Dokument Nr. 193, p. 356

- ^ Cornelius Grebe (2010). Reconciliation Policy in Germany 1998–2008, Construing the 'Problem' of the Incompatibility of Paid Employment and Care Work. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. p. 92. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91924-9. ISBN 978-3-531-91924-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

However, the 1977 reform of marriage and family law by Social Democrats and Liberals formally gave women the right to take up employment without their spouses' permission. This marked the legal end of the 'housewife marriage' and a transition to the ideal of 'marriage in partnership'.

- ^ Comparative Law: Historical Development of the Civil Law Tradition in Europe, Latin America, and East Asia, by John Henry Merryman, David Scott Clark, John Owen Haley, p. 542

- ^ Denso, Christian (13 August 2011). "RAF: Gefangen in der Geschichte". Die Zeit. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Max Otte; Jürgen Greve (2000). A rising middle power?: German foreign policy in transformation, 1989–1999.

- ^ Frank Fischer, "Von Der 'Regierung Der Inneren Reformen' zum 'Krisenmanagement': Das Verhältnis Zwischen Innen- und Aussenpolitik in der Sozial-Liberalen Ära 1969–1982". ["From the 'government of internal reforms' to 'crisis management': the relationship between domestic and foreign policy in the social-liberal era, 1969–82"] Archiv für Sozialgeschichte (January 2004), Vol. 44, pp. 395–414.

- ^ Jonathan Story, "The launching of the EMS: An analysis of change in foreign economic policy." Political Studies 36.3 (1988): 397–412.

- ^ Talk by Hans-Jochen Vogel Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine on 21 October 2002

- ^ Gregor Schöllgen: Willy Brandt. Die Biographie. Propyläen, Berlin 2001. ISBN 3-549-07142-6

- ^ quoted in: Gregor Schöllgen. Der Kanzler und sein Spion. Archived 13 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine In: Die Zeit 2003, Vol. 40, 25 September 2003

- ^ Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- ^ Goda, Norman J. W. (2007). Tales from Spandau: Nazi Criminals and the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–149. ISBN 978-0-521-86720-7.

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Der Naumann-Kreis in Zukunft braucht Erinnerung

- ^ Tetens, T.H. The New Germany and the Old Nazis, New York: Random House, 1961 pages 37–40.

- ^ "Germany's post-war justice ministry was infested with Nazis protecting former comrades, study reveals". The Daily Telegraph. 10 October 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Quint, Peter E (1991), The Imperfect Union; Constitutional Structures for German Unification, Princeton University Press, p. 14

- ^ Kommers (2012), p. 308.

- ^ Texas Law: Foreign Law Translations 1973, University of Texas, archived from the original on 20 December 2016, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Kommers (2012), p. 309.

- ^ David H Childs and Jeffrey Johnson, West Germany: Politics And Society, Croom Helm, 1982 [1] Archived 19 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Giersch, Herbert (1992). The fading miracle : four decades of market economy in Germany. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35351-3. OCLC 24065456.

- ^ "Zusammenfassende Übersichten – Eheschließungen, Geborene und Gestorbene 1946 bis 2015". DESTATIS – Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ "Population by area in 1,000". DESTATIS – Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ FOWID, Religionszugehörigkeit Bevölkerung 1970–2011 (online Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine; PDF-Datei; 173 kB)

- ^ Includes Protestants outside the EKD.

- ^ Pollack, D.; Rosta, G.; West, D. (2017). Religion and Modernity: An International Comparison. Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-880166-5. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "The Impact of the First World War and Its Implications for Europe Today | Heinrich Böll Stiftung | Brussels office – European Union". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ UEFA.com. "Season 1972 | UEFA EURO 1972". UEFA.com. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ UEFA.com. "Season 1980 | UEFA EURO 1980". UEFA.com. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Report: West Germany systematically doped athletes". USA Today. 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Study Says West Germany Engaged in Sports Doping". The New York Times. 8 August 2013.

- ^ "Report exposes decades of West German doping". France 24. 5 August 2013.

- ^ "West Germany cultivated doping culture among athletes: report". CBC News. 5 August 2013.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World Records 2014. 2013 Guinness World Records Limited. pp. 257. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

Sources

[edit]- Abraham, Katharine G.; Houseman, Susan N. (1994). "Does employment protection inhibit labor market flexibility? Lessons from Germany, France, and Belgium". In Rebecca M. Blank (ed.). Social Protection versus Economic Flexibility: Is There a Trade-Off?. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-05678-3.

- Ardagh, John (1996). Germany and the Germans. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140252668.

- Banister, David (2002). Transport Planning. Spon. ISBN 9780415261715.

- Bezelga, Artur; Brandon, Peter S. (1991). Management, Quality and Economics in Building. Spon. ISBN 9780419174707.

- Blackburn, Robin (2003). Banking on Death: or, Investing in Life: the History and Future of Pensions. Verso Books. ISBN 9781859844090.

- Braunthal, Gerard (1994). The German Social Democrats since 1969: a Party in Power and Opposition. Westview Press. ISBN 9780813315355.

- Callaghan, John T. (2000). The Retreat of Social Democracy. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719050312.

- Collings, Justin (2015). Democracy's Guardian: A History of the German Federal Constitutional Court. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cooke, Lynn Prince; Gash, Vanessa (2007), "Panacea or Pitfall? Women's Part-time Employment and Marital Stability in West Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States", GeNet Working Paper, Gender Equality Network

- Glatzer, Wolfgang (21 August 1992). Recent Social Trends in West Germany, 1960–1990. International Research Group on the Comparative Charting of Social Change in Advanced Industrial Societies. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773509092 – via Google Books.

- Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D. (2001). Development and Crisis of the Welfare State. Parties and Policies in Global Markets. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226356471.

- Kaplan, Gisela (2012). Contemporary Western European Feminism. Routledge. ISBN 9780415636810.

- Kommers, Donald P. (1997). The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822318385.

- Kommers, Donald P. (2012). The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany (3rd ed.). Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822352662.

- Lane, Peter (1985). Europe Since 1945: an Introduction. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 9780389205753.

- Patton, David F. (1999). Cold War Politics in Postwar Germany. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312213619.

- Potthoff, Heinrich; Miller, Susanne (2006). The Social Democratic Party of Germany 1848–2005. Translated by Martin Kane. Dietz Verlag J. H. W. Nachf. ISBN 9783801203658.

- Power, Anne (2002). Hovels to High Rise: State Housing in Europe Since 1850. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415089357.

- Pridham, Geoffrey (1977). Christian Democracy in Western Germany: the CDU/CSU in Government and Opposition 1945–1976. Croom Helm. ISBN 9780856645082.

- Schäfers, Bernhard (1998). The State of Germany Atlas. Routledge. ISBN 9780415188265.

- Scheffer (2008). Burned Bridge: How East and West Germans Made the Iron Curtain. ISBN 9781109097603.[full citation needed][failed verification]

- Schewe, Dieter; Nordhorn, Karlhugo; Schenke, Klaus (1972). Survey of Social Security in the Federal Republic of Germany. Translated by Frank Kenny. Bonn: Federal Minister for Labour and Social Affairs.

- Schiek, Dagmar (2006). "Agency work – from marginalisation towards acceptance? Agency work in EU social and employment policy and the 'implementation' of the draft directive on agency work into German law". German Law Journal (PDF). 5 (10): 1233–1257. doi:10.1017/S2071832200013195. S2CID 141058426.

- Silvia, Stephen J.; Stolpe, Michael (2007). "Health Care and Pension Reforms". AICGS Policy Report (PDF). 30. American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-933942-08-7.

- Thelen, Kathleen Ann (1991). Union of Parts: Labor Politics in Postwar Germany. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801425868.

- Tomka, Béla (2004). Welfare in East and West: Hungarian Social Security in an International Comparison, 1918–1990. Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 9783050038711.

- Williamson, John B.; Pampel, Fred C. (2002). Old-Age Security in Comparative Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195068597.

- Wilsford, David, ed. (1995). Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe: a Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313286230.

- Winkler, Heinrich August (2007). Sager, Alexander (ed.). Germany: The Long Road West, Volume II: 1933–1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926598-5.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann, eds. (1997) [1991]. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80793-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Bark, Dennis L., and David R. Gress. A History of West Germany Vol 1: From Shadow to Substance, 1945–1963 (1992); ISBN 978-0-631-16787-7; vol 2: Democracy and Its Discontents 1963–1988 (1992) ISBN 978-0-631-16788-4

- Berghahn, Volker Rolf. Modern Germany: society, economy, and politics in the twentieth century (1987) ACLS E-book online

- Hanrieder, Wolfram F. Germany, America, Europe: Forty Years of German Foreign Policy (1989) ISBN 0-300-04022-9

- Henderson, David R. "German Economic Miracle." The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2008).

- Jarausch, Konrad H. After Hitler: Recivilizing Germans, 1945–1995 (2008)

- Junker, Detlef, ed. The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War (2 vol 2004), 150 short essays by scholars covering 1945–1990

- MacGregor, Douglas A. The Soviet-East German Military Alliance, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Main, Steven J. "The Soviet Occupation of Germany. Hunger, Mass Violence and the Struggle for Peace, 1945–1947." Europe-Asia Studies (2014) 66#8 pp. 1380–1382.

- Maxwell, John Allen. "Social Democracy in a Divided Germany: Kurt Schumacher and the German Question, 1945–52." PhD dissertation, West Virginia University, 1969.

- Merkl, Peter H. ed. The Federal Republic of Germany at Fifty (1999)

- Mierzejewski, Alfred C. Ludwig Erhard: A Biography (2004) online Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Pruys, Karl Hugo . Kohl: Genius of the Present : A Biography of Helmut Kohl (1996)

- Schwarz, Hans-Peter. Konrad Adenauer: A German Politician and Statesman in a Period of War, Revolution and Reconstruction (2 vol., 1995) excerpt and text search vol 2; also full text vol 1 Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine; and full text vol 2 Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, Gordon, ed, Developments in German Politics (1992) ISBN 0-8223-1266-2, broad survey of reunified nation

- Smith, Helmut Walser, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History (2011) pp. 593–753.

- Weber, Jurgen. Germany, 1945–1990 (Central European University Press, 2004) online edition

- Williams, Charles. Adenauer: The Father of the New Germany (2000) Online Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

Primary sources

[edit]- Beate Ruhm Von Oppen, ed. Documents on Germany under Occupation, 1945–1954 (Oxford University Press, 1955) online

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to West Germany at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to West Germany at Wikimedia Commons