Pippa Garner

Pippa Garner | |

|---|---|

| Born | Philip Garner May 22, 1942 Evanston, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 30, 2024 (aged 82) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Drawing, performance, sculpture |

| Movement | Funk art, Nut art |

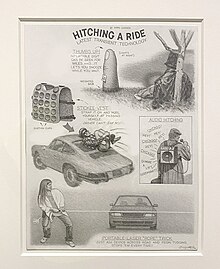

Pippa Garner (May 22, 1942 – December 30, 2024) was an American artist, illustrator, industrial designer, and writer known for making parody forms of consumer products and custom bicycles and automobiles.[1] Garner authored The Better Living Catalog (1982)[2] and Utopia—or Bust! Products for the Perfect World (1984) and worked as an illustrator for the Los Angeles magazine and Car & Driver for many years.[3] Garner exhibited internationally at STARS gallery in Los Angeles, Jeffrey Stark gallery in New York, the Kunsthalle Zürich in Switzerland, and the Kunstverein Munich in Munich, amongst other institutions.[4][5]

Work

[edit]Born on May 22, 1942,[6][7] Garner began her career in the 1970s as a performance artist in Los Angeles.[8] She had been a U.S. Army Combat Artist in the Vietnam War, and was drafted while working at an assembly line at a car plant. Garner was assigned to the 25th Infantry, the only division with a Combat Art Team (CAT).[9] CAT tasked soldier and civilian artists with documenting the Vietnam War in the forms of sketches, illustrations, and paintings to be collected by the U.S. Army for (in their words) "the annals of military history". This is where Garner learned to draw, and, after a trip to Japan during which she purchased a camera, take photographs.[10]

Garner went to the Automotive Design department at ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles after she was discharged,[9] but was expelled after her first year. For a year-end project, she submitted, Un(tit)led (Man with Kar-Mann), circa 1969–72, it was a sculpture of a classic 1960s-style silver and white sedan accentuated by a male body from the waist down in the car's back. One human leg is lifted like a dog urinating. The work was last seen in the 1970s, and only photographs of the work exist.[11]

In 1974, Garner modified a Chevrolet automobile to appear to be driving backwards while it moved forwards and vice-versa. Titled, Backwards Car, 1974, the artwork-like-invention was featured in Esquire in 1975. Garner's work has often been described as a "critique of car culture", reflecting on the US fascination with overbuilt, supersized machines.[12] The work was noticed by San Francisco artists such as Ed Ruscha, Chris Burden, Nancy Reese, and the collective Ant Farm. Following the promotional feature of the artwork in Esquire, she began a long-term collaboration with some of these artists, especially Chip Lord of Ant Farm.[13]

Later, she appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson wearing her infamous Half-Suit, 1982. Additional appearances included the Merv Griffin Show and several other talk shows where she showcased her satirical consumer product "inventions." Similar inventions and artworks were shown in publications such as Car & Driver, Rolling Stone, Arts & Architecture and Vogue.[14]

In the 1980s, Pippa transitioned to a different gender as part of what she considered an "art project to create disorientation in my position in society, and sort of balk any possibility of ever falling into a stereotype again."[15] In an interview musician and visual artist Hayden Dunham in 2021, Pippa expressed these sentiments around gender and transition: "There was something that always seemed odd about being saddled with a gender, or being isolated by your gender. Because the advertising, consumerism, in the background in my life, was very much gender-oriented. There were things for women and things for men. It was all-out masculinity or all-out femininity, macho or made up. And if you didn’t feel that yourself, you felt uncomfortable."[16]

Garner has been noted as a predecessor to the Kardashian beauty industrial complex as well as Paul Preciado’s Testo Junkie, from navigating the psych medical system to purchasing surgeries abroad on her transition, which jump started with "black market hormones" in the 1980s. Garner says in conversation with writer and artist Fiona Alison Duncan, who as working on the artist's narrative biography, "The concept of sex-change as a form of consumer technology began to intrigue me".[17]

Garner participated in Trappings, an artwork by Two Girls Working: Tiffany Ludwig and Renee Piechocki. During her interview for the project, she described her transition as a kind of artistic expression.[18][19] Pippa appeared on the show Monster Garage as a guest artist.[20]

In 1997, Garner showed in Hello Again!, a "recycled art-focused" show which opened at the Oakland Museum[21] and travelled throughout North America. The show, curated by Susan Subtle, featured Garner alongside Mildred Howard, Leo Sewell, Clayton Bailey, Claire Graham, Jan Yager, Remi Rubel, Mark Bulwinkle, and others.

In 2017, Garner had a solo show at Redling Fine Art, Los Angeles where she presented sculptures, drawings, and videos.[22]

A selected retrospective was on view at JOAN gallery in Los Angeles in November and December 2021.[23]

Immaculate Misconceptions

[edit]Garner was known for her Immaculate Misconceptions projects that she created throughout her artistic practice. The series consists of hundreds of inventions, most of them involving repurposing household consumer products into gadgets or absurd devices. For example the ironic "Hurl-A-Burger" machine is a type of catapult designed to "promote cultural exchange" by launching fast food over international border walls.[24][25]

Death

[edit]Garner died on December 30, 2024, following a battle with leukemia. She was 82.[26][27]

Published works

[edit]- Philip Garner's Better Living Catalog: 62 Absolute Necessities for Contemporary Survival, 1982 by Putnam Publishing Group[28]

- Utopia—or Bust! Products for the Perfect World, 1984 by Putnam Publishing Group.[29]

- Garner's Gizmos & Gadgets, 1987 by Perigee Trade.[30]

Exhibitions

[edit]- Pippa Garner: Act Like You Know Me, co-curated by Fiona Alison Duncan, Maurin Dietrich, Daniel Baumann, and Otto Bonnen at Kunstverein Munich (2022) and Kunsthalle Zürich (2023)

Collections

[edit]Garner's work is in the collection of the Audrain Auto Museum of Rhode Island,[12] a selection of her photographs are held in the Contemporary Art Library archives.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Boldly Queer, Proudly Off-Kilter World of Pippa Garner". Vogue. October 5, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Garner, Philip. Philip Garner's Better Living Catalog. New York, NY: Delilah, 1982. Print.

- ^ Garner, Philip. Utopia-- or Bust!: Products for the Perfect World. New York: Delilah Communications, 1984. Print.

- ^ "Pippa Garner - Exhibitions - Kunsthalle Zürich". www.kunsthallezurich.ch. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "PORTFOLIO: PIPPA GARNER". Artforum. Vol. 61, no. 2. October 2022. ISSN 0004-3532. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Merrick, Abby (April 15, 2024). "HE 2 SHE: Artist Pippa Garner Hacks Her Gender". Public Seminar. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Duncan, Fiona Alison (October 28, 2023). "ACT LIKE YOU KNOW ME by Pippa Garner". NOVEMBRE GLOBAL. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Duncan, Fiona (Autumn 2018). "Interview Pippa Garner". Spike (57). Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Interview Pippa Garner". Spike Art Magazine. September 25, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Pippa Garner". White Columns. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ "AUTO EROTICS Brit Barton on Pippa Garner at the Kunstverein München". www.textezurkunst.de. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Diehl, Travis (February 11, 2022). "Pippa Garner's gender-bending satire on America's consumer culture". Financial Times. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Bush, Bill (December 5, 2011). "Paradise Notwithstanding: This Artweek.LA (December 5-11, 2011)". HuffPost.

- ^ Artist Bio/Resume at Lois Lambert Gallery, http://www.loislambertgallery.com/index.php#mi=1&pt=0&pi=41&s=0&p=0&a=0&at=0 Archived 2015-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ludwig, Tiffany, and Renee Piechocki. "Misc. Pippa Garner." Trappings: Stories of Women, Power and Clothing. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2007. 71–78. Print.

- ^ Barna, Ben (May 19, 2021). "Pippa Garner and Hayden Dunham on the Struggle of Being Inside Bodies". Interview Magazine. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ marc (May 14, 2021). "In Words". Various Artists. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Her Trappings interview is available here.

- ^ Miller, Nicole (Fall 2019). "Everything Is Objectification: An Interview with Pippa Garner". X-tra. 22 (1). Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Monster Garage: Jet Boat / Car". Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ "Enviro-Friendly Art". Waste360. December 1, 2004.

- ^ Knight, Christopher (May 6, 2017). "Pippa Garner at Redling Fine Art: Vehicles for clever satire - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Fiona Alison Duncan - Grantees - Arts Writers Grant". www.artswriters.org. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Reizman, Renée (November 15, 2021). "Pippa Garner's Household Inventions Reimagine the World". Hyperallergic. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Martinez, Christina Catherine (January 2022). "Pippa Garner". Artforum. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ "Pippa Garner, Revolutionary Artist Known for Subversive Humor, Dies at 82". Hypebeast. January 2, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Alex Greenberger (January 2, 2025). "Pippa Garner, Inventive Artist Who Satirized Consumerism, Dies at 82". ART News.

- ^ Philip Garner's Better living catalog. OCLC 607059699. Retrieved October 21, 2022 – via WorldCat.

- ^ "Utopia - or Bust! Products for the perfect world". WorldCat. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Garner's Gizmos and Gadgets". WorldCat. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Pippa Garner". The Contemporary Art Library. Retrieved July 30, 2022.