Photocatalytic concrete

Photo-catalytic concrete is a formulation of concrete used as pavers and other structural concrete that includes titanium dioxide (TiO2) as an admixture or superficial layer. Titanium dioxide is a heterogeneous photocatalyst that uses sunlight and moisture to absorb and render oxides of nitrogen (NO and NO2) into nitrate ions (NO3−), which are then either washed away by rain or soaked into the concrete to form stable compounds.[1]

History

[edit]The technique of photocatalytic concrete was firstly used in architecture during construction of the Italian Church of Dio Padre Misericordioso. Richard Meier construction also known as Jubilee Church[2] is confined to 2000 anniversary of the Christianity that was celebrated in 2000. In order to avoid frequent cleanings of new church's concrete "sails", new development was used - white self-cleaning coating of the walls.[3] However, back then it wasn't known that this colouring plaster containing titanium dioxide and white pigment absorbs exhaust gases and other elements of city fog. This discovery raised question of wide application of similar materials in urban construction. According to studies, the air at a distance of 2.5 m from a facade coated with titanium dioxide contains 70% less various combustion products than other city buildings. So the people inhale less harmful substances while passing by the buildings treated this way. Options for using photocatalytic cement to cover asphaltic roads are also being considered. As an experiment it was used at 230-meter stretch of highway near Milan. Measurements allowed to see that at this road average traffic load of 1000 vehicles per hour, the reduction of nitrogen oxides in the air at ground level was 60%.[4] Some were skeptical about this discovery: in their opinion, it is necessary to reduce the level of harmful substances emissions, and not to eliminate their consequence - smog. Moreover effectiveness of practically all catalysts weakens as time passes.

Mechanism

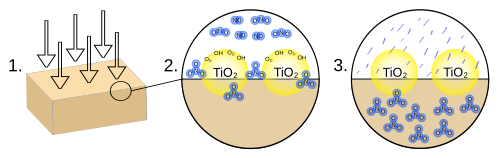

[edit]When titanium dioxide is exposed to ultraviolet radiation from sunlight, it absorbs the radiation and electron excitation occurs. The following reactions then occur on the surface of the titanium dioxide crystals:

Photolysis of water:

- H2O → H+ + OH (hydroxyl radical) + e−

- O2 + e− → O2− (a superoxide ion)

The overall reaction is therefore:

- H2O + O2 → H+ + O2− + OH

The hydroxyl radical is a powerful oxidizing agent and can oxidize nitrogen dioxide to nitrate ions:

- NO2 + OH → H+ + NO3−

The superoxide ion is also able to form nitrate ions from nitrogen monoxide:

- NO + O2− → NO3−

The oxidation of NOx to nitrate ions occurs very slowly under normal atmospheric conditions because of the low concentrations of the reactions. The photochemical oxidation with the aid of titanium dioxide is much faster because of the energy absorbed by the coating on the block and also because the reactants are held together on the surface of the block. The reaction using titanium dioxide shows a greater oxidizing power than most other metal-based catalysts.

Photo-catalytic blocks have replaced ordinary paving in around 30 towns in Japan, originally having been tested in Osaka in 1997 and have been used in the City of Westminster (London)[citation needed]. The aim of these blocks is to reduce atmospheric pollution levels and therefore lower the amount of photochemical smog.

- Ultraviolet radiation is absorbed by the titanium dioxide, which causes the photolysis of water into superoxide ions and hydroxyl radicals.

- Nitrogen oxides react with the superoxide ions and the hydroxyl radicals to form nitrate ions.

- The nitrate ions are absorbed into the block and form stable compounds.

References

[edit]- ^ Sikkema, Joel K (2003). "Photocatalytic degradation of NOx by concrete pavement containing TiO2". Iowa State University. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "La Chiesa Dio Padre Misericordioso". diopadremisericordioso.it. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ "PHOTOCATALYTIC CONCRETE". formworkcontractorsbrisbane.com. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta (2006-11-22). "Architecture in Italy goes green". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2024-02-18.