Operation South

| Operation South | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Simba rebellion during the Congo Crisis | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Banyamulenge militias |

Simba rebels

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Laurent-Désiré Kabila Idelphonse Massengo | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC)

|

"Armée Populaire de Libération"

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 2,400 |

Thousands of rebels c. 123–200 Cubans | ||||||

Operation South (French: Opération Sud) (September 1965 – July 1966) was a military offensive conducted by the forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Kivu against insurgents during the Simba rebellion. It was carried out by the DR Congo's regular military, the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC), mercenaries, and various foreign soldiers employed by Belgium and the United States. The operation aimed at destroying the remaining Simba strongholds and ending the rebellion. Though the insurgents were supported by allied Communist Cubans under Che Guevara and Rwandan exile groups, the operation resulted in the conquest of most rebel-held areas and effectively shattered the Simba insurgents.

Background

[edit]Following its independence in 1960, the Republic of the Congo became the subject to a series of political upheavals and conflicts collectively termed the "Congo Crisis".[5] In 1964, various insurgent groups launched a major rebellion in the eastern regions, inflicting heavy losses on the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC), the national military.[6] The rebels captured much of Orientale Province and Kivu, proclaimed a leftist "People's Republic",[7] and declared their militias the "Armée Populaire de Libération" (APL). However, the rebels became more commonly known as "Simbas" and were never able to unite organisationally or politically.[8][7][9] Regardless, they were perceived as anti-Western and anti-colonialist socialists by outside powers[1] and thus various sympathetic foreign states, including Cuba, began to funnel aid to the Simba insurgents.[10][11] On the opposing side, the Congolese government received backing by Western powers such as the United States whose CIA sent Cuban exiles as military pilots (called "Makasi") to support the ANC.[11] President Joseph Kasa-Vubu appointed Moïse Tshombe new Prime Minister to solve the crisis.[6] Tshombe had previously led the separatist State of Katanga, whose military had consisted of the Katangese Gendarmerie and supportive mercenaries.[6][12]

After negotiations with the Simbas failed, Tshombe recruited a large number of ex-gendarmes and mercenaries to bolster the ANC.[13][14] These troops were led by Mike Hoare and organized as units termed "Commandos",[13] relying on speed and firepower to outgun and outmaneuver the insurgents.[15] The restrengthened security forces were able to halt the Simbas' advance.[13] In late 1964, the Congolese government and its allies, including Belgium and the United States, organized a major counter-offensive against the Simba rebels. This campaign resulted in the recapturing of several settlements in northeastern Congo, most importantly Stanleyville. The mercenaries played a major role in the offensive, bolstering their reputation and causing Tshombe to extend their contracts as well as enlist more of them.[16]

In January 1965, Hoare was promoted to lieutenant colonel by General Joseph-Desiré Mobutu, chief of staff of the ANC,[17] and given command of a military zone termed "Operation North-East" in Orientale Province.[18] From March to June 1965, ANC contingents and mercenaries under Hoare and Jacques Noel organized Operations "White Giant" and "Violettes Imperiales", military offensives aimed at retaking the areas bordering Uganda, Sudan, and the Central African Republic. These operations cut off important rebel supply routes, recaptured a number of large towns in northern Orientale Province, and deprived the insurgents of local gold mines.[18][19] This greatly weakened the Simba rebellion.[20] By mid-1965, the Simbas had lost a majority of their territory in northeastern Congo.[21]

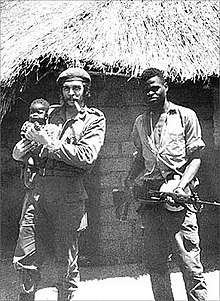

From April 1965, the Simba rebels were reinforced by several waves of Communist Cuban volunteers under Che Guevara, most of them Afro-Cubans. These intended to provide training to the rebels, and also assisted in logistics.[22][1] In contrast, other forms of foreign support for the rebels declined as their international allies fell into disputes.[22] The Cubans were soon disappointed by the lack of fighting ability of the Simba insurgents and their infighting leadership.[23] By late 1965, the remaining Simba forces mainly consisted of Laurent-Désiré Kabila's followers; other Simba factions such as the ones of Gaston Soumialot and Christophe Gbenye had been largely defeated.[1][24] Regardless, Soumialot and Gbenye continued to pose as the insurgency's leaders in exile,[1][25] while also quarreling with each other. On 5 August 1965, Soumialot declared in Egypt that the Congolese "Revolutionary Government" was dissolved and Gbenye had been dismissed as President of the People's Republic. The exiled Simba leadership in Egypt and Sudan subsequently intensified their infighting, with two rebel leaders even being murdered. Annoyed at this unrest, the Egyptian and Sudanese government responded by expelling many Simba leaders and interning other members of the rebel movement.[26]

Prelude

[edit]

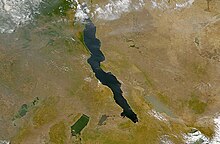

Following the successes of Operations White Giant and Violettes Imperiales, the ANC planned a new offensive, "Operation South". This campaign would target the last major Simba stronghold which was located at Fizi-Baraka in South Kivu. This was the center of the remaining rebel-held territory which stretched for 240 kilometres (150 mi) along Lake Tanganyika, and reached 260 kilometres (160 mi) inland.[20][1] The campaign area was designated as covering the territory between Albertville, Uvira, and Bukavu in the north and Mwenga, Kalole, Wamaza, Kasongo, Kongolo, and Nyunzu. This region was difficult to access and traverse, dominated by Mitumba Mountains. The local rebels still received supplies from foreign states; these were shipped across Lake Tanganyika.[1][27] To defeat these rebel holdouts, the government forces thus had to cut the naval supply routes.[28] Hoare planned to combine ground-based, amphibious, and airborne attacks for the upcoming operation.[27] As he outlined the operation, he attempted to avoid mistakes made in a previous amphibious attack, Operation White-Chain,[29] by enlisting a large naval force. He also spread false information about an alleged offensive (termed "Operation Wingate") across the mountains, hoping to deceive the insurgents.[30] After realizing the extent of the Communist Cuban support for Kabila's rebels, the Belgian and CIA agents in the Congo urged Hoare to push ahead with the planned offensive.[31]

Even as preparations for Operation South proceeded,[32] the Congolese central government suffered from considerable political infighting. Thanks to Tshombe's growing popularity across the country due to his successes against the insurgents, Tshombe and his party CONACO had won a majority in the parliamentary elections of March–April 1965. Despite this, President Kasa-Vubu called for a "government of national unity", leading to a fierce political struggle between the President and Tshombe over the next months.[33]

Opposing forces

[edit]Congolese government and allies

[edit]The government forces involved in Operation South were headed by Lieutenant Colonel Eustache Kakudji, a Congolese ANC officer. A Belgian officer, Lieutenant Colonel Roger Hardenne, acted as Kakudji's chief of staff.[1][34] In addition, Louis Bobozo played a major role in the operation.[35] Operation South's headquarters was placed at Albertville,[1] where the local Belgian military mission was also located and assisted the ANC.[31] Hoare once again led the mercenary contingent, and was chiefly involved in carrying out the amphibious element of the offensive.[27] Regular ANC troops played a marginal role in the operation[20] which was mainly carried out by mercenaries and ex-Katangese gendarmes.[20][36] The ANC soldiers were often poorly trained and suffered under low morale; their officers were mostly Belgians.[37] In contrast, the mercenaries and gendarmes involved in the operation were regarded as relatively effective, though they also treated civilians and POWs brutally and clashed with other ANC troops.[36] Tshombe deliberately did not deploy some of his most well trained and loyal units against the Simbas, instead conserving their strength for future political struggles in the DR Congo.[38] The mercenaries and ex-Katangese gendarmes were well supplied with vehicles, including several trucks, jeeps, and at least one Ferret armoured car. Overall, the following units were deployed during Operation South: 5 Commando,[1] 6 Commando, 9 Commando,[39] Codoki Commando,[20] 5 Infantry Battalion, 8 Infantry Battalion, 13 Infantry Battalion,[39] 14 Infantry Battalion, and Kongolo Battalion.[1] Overall, about 2,400 soldiers were reportedly involved.[40]

To facilitate the planned amphibious landings as well as naval transportation, the government forces included the so-called Force Navale ("Naval Force")[1] or Force Navale Congolaise.[41] This contingent initially consisted of six machine gun-armed Chris-Craft P boats and the armed trawler Ermans captained by Iain Peddle, manned by mercenaries.[1][42] Several civilian ships were also provided by the Belgian navigation company operating on Lake Tanganyika, including the steamer Urundi, the tug Ulindi, and the barges Uvira as well as Crabbe. These ships carried soldiers and vehicles to allow the planned landing force to quickly expand its beachhead.[27] However, the CIA deemed these naval assets to be too few as well as lackluster in quality to perform a naval blockade in the upcoming operation. The agency thus ordered Thomas G. Clines, Deputy Director of Plans Special Operations Division maritime branch, to create a new covert navy on Lake Tanganyika.[43] Clines acquired several Swift Boats manned by CIA-employed Cubans;[1] these Cubans belonged to the Movimiento Recuperación Revolucionaria (MRR), a CIA-organized anti-Castro maritime rebel group.[44] Locally, CIA agent Jordy McKay and later Navy SEAL James M. Hawes oversaw the creation of the covert navy, and personally led the local naval operations.[3] In addition, the pro-government force was supported by eight to twelve T-28 and two to four Douglas A-26 Invader military aircraft, one Bell 47 helicopter, and a Douglas DC-3, crewed by "Makasi" pilots.[1][42] The Cuban CIA agents were strongly motivated by their hatred for their Communist compatriots; upon realizing that Guevara was one of the enemy commanders, they wanted to kill him at all costs.[45] Some Belgian officers and pilots involved in Operation South were also connected to or even employed by the CIA.[46]

The pro-government forces were also backed by some tribal groups. In South Kivu, the Banyamulenge sided with security forces,[47] as they had largely mistrusted the Simba rebels from the start. The Banyamulenge feared the insurgency was mainly a ploy by the Bembe people to steal their cows.[48] These fears were realized when the rebels, lacking supplies due to their defeats, started killing Banyamulenge cows for food. In revenge, the Banyamulenge organized militias and began to hunt for the rebels.[47][48]

Simba rebels and allies

[edit]

The Simba forces opposing Operation South were officially part of the APL's "Eastern Front" commanded by Laurent-Désiré Kabila,[1] head of the rebels' Kabila-Massengo faction. This faction was among the most left-leaning groups of the insurgency.[8] Kabila was often absent from the frontlines to visit the exiled Simba officers;[23] his co-commander, Idelphonse Massengo, was seldom present in the war zone.[49] Officially, Fizi hosted the APL's 2nd (Southern) Brigade, split into the 3rd, 7th, and 8th Battalions. In reality, the APL was generally disorganized and lacked a firm structure.[7] Kabila's forces were mainly recruited from and backed by the local Bembe as well as Rwandan exiles.[1] The latter had involved themselves in the Simba rebellion to get foreign support for their own plans to invade Rwanda.[21] By April 1965, several thousand pro-Simba Rwandan militants operated in eastern Congo.[21] The Rwandan exiles were centered at a base in Bendera.[1] The fighting quality of the Simba rebels fluctuated greatly; sometimes, they displayed discipline and even suicidal bravery,[50][39][37] but in other cases, they fled without even using their weapons.[23] The Cuban training generally improved the capabilities of Kabila's troops.[37]

Che Guevara's force included about 123 to 200 Communist Cubans in total.[51] They set up a training center at Luluabourg Mountain, close to Lake Tanganyika, and helped to coordinate the flow of supplies across the lake.[1] Though the Cubans helped to improve the fighting capabilities of the Simbas and Rwandans,[52][22] the Simba leadership disagreed with the Cubans over ideology and strategy, resulting in tensions that undermined any military cooperation.[53][1] Though Guevara had a low opinion of Kabila and other frontline Simba commanders, he despised Soumialot as the latter still pretended to lead forces and took money despite having fled the country.[54] Around late August/early September 1965, Soumialot visited Havana and met Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Soumialot's claims about the military situation differed drastically from Guevara's reports; Castro consequently became mistrustful of Guevara and sent teams to identify which version of events was true.[40] One of those sent, Emilio Aragonés (alias Tembo), started to bitterly argue with Guevara.[24] Many Cubans became demotivated due to the lackluster morale and quality of their Simba allies.[23]

Operation

[edit]Phase One ("Operation Banzi")

[edit]Battle for Baraka

[edit]

The first phase of Operation South, dubbed "Operation Banzi",[27] began on 27 September 1965.[39][42][a] This initial attack consisted of two amphibious attacks on Baraka and a ground-based assault from Lulimba toward Fizi. The amphibious landings were conducted by 5 Commando's "Force John-John" under Major John Peters and "Force Oscar" under Captain Hugh van Oppen, while the ground offensive was carried out by "Force Alpha" under Major Alistair Wicks.[39] The naval forces moved out of the small port of Kabimba at night; to conserve fuel, the tugs towed the barges and the Ermans towed the Swift Boats. When these troops arrived near Baraka, Hoare ordered the CIA aircraft the bomb the area, while a seven-man reconnaissance party was sent ashore.[55] However, issues quickly emerged; a storm, the darkness, and rough waters hindered the ships. Peters' reconnaissance group landed at the wrong beach, and discovered that their radios were too weak to communicate with their comrades. One PT boat broke down and began to drift helplessly on the lake.[56] Despite already being two hours behind schedule and lacking proper reconnaissance, Hoare decided to risk sending his forces ashore.[57]

The main landing forces were on the beach within 45 minutes near Baraka. The rebels responded with machine gun fire and mortars from the nearby city, pinning down the government troops.[55][56] The attack could only continue when the armed boats and ships provided accurate covering fire, directed by CIA agent McKay, to silence the rebel positions.[55][43] As the landing parties advanced into Baraka, they encountered heavy resistance.[39] While Force Oscar pushed into the city center, Force John-John unsuccessfully attempted to encircle the settlement. Force John-John was repulsed by the insurgents amid heavy losses on both sides. Four mercenaries were killed and many more were wounded, including Peters; about 120 Simba rebels were killed, including their commander Wasochi Abedi.[57] The ANC troops were only able to fully secure their beachheads after two days of fighting,[39] though the fighting for Baraka continued.[57] At the same time, Force Alpha was stopped by well-prepared rebel defenses near Lubonja. Unable to continue its advance, Force Alpha subsequently retreated and, alongside two ANC companies as well as more heavy equipment, was also ferried across Lake Tanganyika to assist at Baraka.[39] With these additional forces, Hoare was finally able to overwhelm the remaining Simba holdouts in Baraka; at this point, the rebel garrison's discipline broke down, and they resorted to unsuccessful mass charges to drive the government troops from Baraka.[50] Hoare's ships and boats also patrolled the lake to prevent the rebels from being resupplied.[55] However, the overt role of McKay in the landing at Baraka had embarrassed the CIA and upset the United States Department of State; thus, McKay was removed from his post despite his effective leadership and replaced by James M. Hawes.[3]

Southern advance by government forces

[edit]After Che Guevara's Cubans were informed of Operation South's start and Baraka's capture, they sent 14 men under Martínez Tamayo to set up ambushes in the Lugoma area, while trying to discern the government offensive's aims. Guevara's second-in-command Víctor Dreke realized that the operation aimed at closing the lake's supply routes, while forcing the rebels' foreign advisors to evacuate. Over the next days, the rebels repeatedly attacked and retook Baraka, only to be pushed back by renewed government attacks.[40] Around 4 October, the Communist Cubans experienced a crisis when Castro publicly declared that Guevara had resigned all his governmental posts in Cuba. Though the exact reason on why Castro made this announcement at the time remains disputed among historians, Guevara regarded the move as a "betrayal of trust".[58] On 5 October, Guevara gathered the Simba, Rwandan, and Cuban officers of the Fizi-Baraka area to discuss their detoriating military situation, as they were running out of areas for guerrilla warfare and had to either retreat or engage in conventional battles.[59] The officers decided to stand and fight; Guevara subsequently penned a harshly worded letter to Castro, criticizing that his superior had trusted Soumialot over him and had not sent the supplies as well as personnel that Che had deemed necessary to continue the fight. Castro never responded to the letter.[60]

The government forces finally secured Baraka on 9 October. They also captured Simba documents at the town, informing them on rebel concentrations in the wider area.[1] While two ANC companies were ordered to secure Baraka, 5 Commando continued its advance inland.[40] The Communist Cubans initially intended to stem the government forces' advance through guerrilla ambushes, but Hoare had planned to be constantly on the offensive, thus forcing the insurgents into conventional battles during which they were at a disadvantage.[40] Hoare's troops overran the Mutumbala Bridge at Tembili after CIA aircraft bombed the location, clearing the road to Fizi.[61][34] This town was defended by 400 Simba insurgents and 10 Cubans under Oscar Fernández Mell (Siki), but the garrison offered little[61] or no resistance.[35] On 10 or 13 October, 5 Commando captured Fizi[61][39] which was then garrisoned by 9 Commando.[39] After this point, the government troops pushed southward,[39] as Hoare had correctly ascertained that the main Cuban camp had to be located west of the Yungu-Kibamba area. He thus tried to cut off their access to the lake and force them into an increasingly small containment zone. The Communist Cuban main force would thus have to choose to secure an escape route to Tanzania or defend Guevara who was at Luluabourg Mountain.[61] Meanwhile, the CIA and ANC naval forces on the lake became increasingly effective at stopping the flow of supplies to the Simbas, gradually starving the rebels of arms and other equipment.[41]

Pushed out of the Fizi-Baraka stronghold, the rebels retreated west and south.[39] Guevara entertained the idea to switch to a guerrilla campaign from the regions' mountains,[61] and his forces thus concentrated at Luluabourg Mountain. Hoare had expected this move. Content to isolate the mountain fortress, the mercenary commander thus continued to take the remaining rebel-held towns. On 12 October, his men captured Lubonja,[62] followed by Makungu a few days later.[39]

On 13 October 1965, both sides were startled to learn that the political crisis over the DR Congo's leadership had escalated. President Kasa-Vubu had removed Tshombe from his post by as a result of their power struggle. The pro-Tshombe parliament twice rejected Kasa-Vubu's proposed new Prime Minister, Évariste Kimba, and the infighting continued.[63] The dismissal of Tshombe unnerved the mercenaries and gendarmes, but also undermined the rebels' cause. Many African countries had justified their support of the Simba rebels with their criticism of Tshombe. Regarding the Simba rebels as defeated, yet their aim of removing Tshombe as fulfilled, various states began to terminate their assistance the rebellion and requested the Communist Cubans to leave the Congo. Having been dismissed from the Cuban government and unwilling to abandon the cause, however, Guevara initially refused to leave.[62] Instead, he planned a counter-attack to regain the initiative and restore the flow of supplies across Lake Tanganyika.[64] To do so, and to buy time for the training of 3,000 Simba rebels in Tanzania, Guevara divided his Cubans in three sections. One force, led by Guevara and Dreke, defended the camp near Kilonwe at Luluabourg Mountain; the second, commanded by Martínez Tamayo (M'bili), would set up defenses at Kibamba's port area; the third under Santiago Terry (Aly) would attempt to retake Baraka.[65] Meanwhile, the government forces continued their advance. On 19 October, 5 Commando captured Kasimia in a combined sea-land-attack,[39] while ANC troops from Bendera overran the Simbas' bases near Yungu on 20 October.[39][61]

Che Guevara's retreat

[edit]A month of disasters without any extenuating circumstances. To the disgraceful fall of Baraka, Fizi, and Lubonja ... we must add ... total discouragement among the Congolese ... The Cubans are not much better, from Tembo and Siki (Aragones and Fernandenz Mell) to the soldiers.

On 23 October, President Kasa-Vubu attended a meeting of African states during which he blamed all ills of the DR Congo on Tshombe, announced a reapprochment with various Leftist states, and the end of all mercenary operations. ANC chief of staff Mobutu was furious about this announcement, refusing to dismiss the mercenaries. This resulted in another power struggle, now between Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu.[65] Meanwhile, Hoare began to directly attack the Communist Cuban camps. On 24 October, mercenaries and ANC troops under Major Peters attacked the Kilonwe camp, nearly killing Guevara himself. The Communist Cubans and their Congolese allies were able to retreat, though suffered several losses and had to leave important equipment behind. On 30 October, Terry's force of 2,000 Simbas and 45 Cubans overran Baraka's small ANC garrison and retook the town. Hoare ordered 5 Commando to immediately counter-attack with support by CIA aircraft. After a hard-fought battle lasting three days, with hundreds of losses on both sides, the government forces secured the town.[67] Meanwhile, the government forces also began a direct attack on the Yungu port at Kibamba, defended by a garrison under Mell and Aragonés. After Swift Boats (manned by Cuban CIA agents) intervened to destroy the rebels' machine gun nests, the port fell to the government troops. The Cubans retreated to Kibamba itself.[68]

Faced with the loss of their bases, morale among the rebels plummeted, and many Rwandans and Communist Cubans wanted to quit the conflict.[52][69] The Cubans also realized that the rebellion was failing and the local population became increasingly hostile.[52] On 1 November, a letter by Cuba's ambassador to Tanzania asked Guevara to abandon the conflict, but he still refused.[69] Despite admitting that the local revolution was "dying", he still felt that the Cubans could not just abandon their Simba allies.[70] Over the next days, the rebels' situation detoriated further; Guevara was informed by his commanders that both the Cuban as well as Rwandan troops were no longer willing to keep fighting. There were also mass desertions by Simbas and Rwandans. CIA aircraft also increasingly attacked Nganja, decimating the local cow herds which had become the rebels' main food source. Deserters and local farmers also showed the remaining rebel camps to the ANC, resulting in more air raids.[69] By mid-November, Guevara realized that the situation had become untenable; his men began destroying documents and any weapons or equipment they could not carry. Guevara contacted Zhou Enlai who suggested that the Cubans could try to link up with the Kwilu rebellion, but the Cuban revolutionary regarded this proposal as unfeasible. Guevara next met with Simba leader Massengo,[71] and offered to fight to the death.[72] However, Massengo told him that the Communist Cubans had no other option than to quit the war zone,[71] as he could not justify Guevara's troops fighting to the end even as the Simbas themselves were giving up. Guevara finally agreed to withdraw.[72]

Guevara's men thus boarded several heavily armed boats on Lake Tanganyika in the night of 20/21 November to leave the Congo for Tanzania.[73] The flight was fraught with continuing disputes. Guevara was still hesitant to leave, sometimes expressing the determination to stay behind or musing to try to link up with the Kwilu rebellion after all. He was also unwilling to leave behind many refugees who begged to be let aboard to Cuban boats. Only at the urgings of his subordinates, Guevara ultimately left.[74] Accounts of the Communist Cuban retreat across Lake Tanganyika differ sharply between those published by the Cuban government on one side and CIA veterans on the other. According to the official government version, the evacuation went flawlessly and encountered no resistance. In contrast, CIA veterans claim that the Communist Cuban boats ran into a naval patrol consisting of the Swift Boat Monty, manned by Cuban CIA agents under skipper Ricardo Chávez. A short firefight ensued, possibly resulting in one or two Communist boats being sunk before the Monty retreated.[73] Some CIA and Belgian sources have also claimed that the government forces were ordered to not engage the fleeing Communist Cubans to avoid an international incident.[46]

By the time of Guevara's departure, the Simba rebellion was effectively defeated.[53] Many rebels also fled into exile; some ultimately relocated to Cuba.[75] The remaining Simba rebels moved further west and south to escape the government offensive. This required ANC contingents to defend the railway lines to Albertville, as well as Kongolo and Niemba from rebel assaults.[39] In February 1966, government forces systematically searched and destroyed the remaining rebel bases. After these efforts, the local government troops were reorganized and Operation South's first phase was declared to be over.[39]

Phases Two and Three

[edit]In April 1966, Operation South's Phase Two was launched. At first, 5 Commando under Major Peters advanced along Lake Tanganyika to Uvira, paralleled by a mixed force of 6 Commando and 5 Infantry Battalion to the west. These two columns cleared rebels on their pathway. After two months of fighting, Phase Three was initiiated. At this point, 5 Commando, 9 Commando, 8 Infantry Battalion, 13 Infantry Battalion, and two platoons of 6 Commando were gathered in Uvira. They then advanced along the Ruzizi River to Bukavu. Meanwhile, other 6 Commando elements and 5 Infantry Battalion moved to link up with the ANC garrison at Mwenga.[39] After the Simbas were driven from the Ruzizi River valley and the area around Uvira, many rebels of Bembe, Furiiru, and Vira ethnicity retreated into South Kivu's Hauts-Plateaux. There, they increasingly clashed with Banyamulenge, forcibly taxing them or stealing their cattle. In response, Banyamulenge militias fought alongside the ANC against the rebel remnants and created a humanitarian corridor to assist civilians escaping from the Hauts-Plateaux to the Ruzizi River and Baraka. This transformed the conflict into an "ethnic war" between Banyamulenge (and the ANC) on one side, and the Bembe, Furiiru, and Vira on the other side. As the Banyamulenge militias were armed by the security forces, they gained the upper hand in the conflict and secured the Hauts-Plateaux for themselves.[48]

The remaining Simba rebels were mainly concentrated along the Pende-Mende-Wamaza-Kongolo road, where they still enjoyed substantial local support. On 14 July, this area was designated as the area for Operation South's Phase Four to contain and eliminate the last insurgents. However, this phase was never carried out due to the outbreak of the Stanleyville mutinies.[39] Regardless, historian Gérard Prunier concluded that most of the remaining Simba rebels were "slaughter[ed]" by the ANC, mercenaries, and Banyamulenge militias.[76]

Aftermath

[edit]In November 1965, Mobutu organized a coup, overthrowing Kasa-Vubu and driving Tshombe into exile. Though Mobutu initially appeared willing to work with Tshombe's CONACO, he gradually undermined it and other political factions in the country to his own advantage.[63] From 1965 to 1967, Mobutu gradually pacified or purged his rivals, while Tshombe's attempts to regain power failed. Tshombe's loyalists in the ANC, namely mercenaries and ex-gendarmes, unsuccessfully attempted to stem this process in the Stanleyville mutinies, only to be defeated and driven into exile.[77] Remnants of the Simba rebels continued to operate in eastern Congo, waging a low-level guerrilla war from bases in remote frontier regions.[78][79]

The Congolese government also rewarded the Banyamulenge for their role in defeating the Simba rebels by favoring them over other local ethnic groups.[48] This resulted in lasting ethnic tensions, contributing to subsequent local revolts and violence.[80]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to researcher Edgar O'Ballance, the operation began on 29 September 1965.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Hudson 2012, Chapter: Operation South and Che Guevara.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, pp. 190, 192–193.

- ^ a b c Kinsey 2023, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Abbott 2014, pp. 3, 8–14.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1998, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Abbott 2014, p. 16.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, p. 73.

- ^ Turner 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Villafana 2017, p. 108.

- ^ a b Kennes & Larmer 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Abbott 2014, pp. 3–14.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1998, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Abbott 2014, pp. 6, 16.

- ^ Abbott 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Rogers 1998, pp. 18–22.

- ^ Rogers 1998, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hudson 2012, Chapter: Operation White Giant.

- ^ Hudson 2012, Chapter: Operation Violettes Imperiales.

- ^ a b c d e Abbott 2014, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Stapleton 2017, p. 244.

- ^ a b c Onoma 2013, p. 206.

- ^ a b c d Mwakikagile 2010, p. 189.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, p. 160.

- ^ Villafana 2017, p. 158.

- ^ O'Ballance 1999, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1986, p. 82.

- ^ Kinsey 2023, p. 112.

- ^ Thomas 1986, pp. 61, 82.

- ^ Thomas 1986, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Mwakikagile 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Hudson 2012, Chapter: General Mobutu's Coup d'État.

- ^ Kennes & Larmer 2016, pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b Rogers 1998, p. 27.

- ^ a b c O'Ballance 1999, p. 91.

- ^ a b Kennes & Larmer 2016, pp. 70–72.

- ^ a b c Mwakikagile 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Kennes & Larmer 2016, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hudson 2012, Chapter: Operation Banzi.

- ^ a b c d e Villafana 2017, p. 153.

- ^ a b Kinsey 2023, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1998, p. 25.

- ^ a b Kinsey 2023, p. 113.

- ^ Kinsey 2023, p. 114.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, p. 192.

- ^ a b Mwakikagile 2010, pp. 200–202.

- ^ a b Prunier 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c d Turner 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 72, 143, 148.

- ^ a b Rogers 1998, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b c Stapleton 2017, p. 245.

- ^ a b Abbott 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 158, 160.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1986, p. 83.

- ^ a b Rogers 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 153–157.

- ^ Villafana 2017, p. 157.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 157–160.

- ^ a b c d e f Villafana 2017, p. 161.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, p. 162.

- ^ a b Kennes & Larmer 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, p. 163.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, p. 195.

- ^ Villafana 2017, p. 164.

- ^ Villafana 2017, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c Villafana 2017, p. 165.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Mwakikagile 2010, p. 199.

- ^ a b Villafana 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2010, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Luntumbue 2020, p. 141.

- ^ Prunier 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Kennes & Larmer 2016, pp. 73–79.

- ^ Prunier 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Villafana 2017, p. 188.

- ^ Turner 2007, pp. 86–87.

Works cited

[edit]- Abbott, Peter (2014). Modern African Wars (4): The Congo 1960–2002. Oxford; New York City: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-076-1.

- Rogers, Anthony (1998). Someone Else's War. Mercenaries from 1960 to the Present. London: HaperCollins Publishing. ISBN 0-00-472077-6.

- Hudson, Andrew (2012). Congo Unravelled: Military operations from Independence to the Mercenary Revolt, 1960–68. Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1907677632.

- Kennes, Erik; Larmer, Miles (2016). The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa: Fighting Their Way Home. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253021502. Archived from the original on 2023-01-11. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- Kinsey, Christopher (2023). The Mercenary: An Instrument of State Coercion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-887278-8.

- Luntumbue, Michel (2020). "Cuban-Congolese families: From the Fizi-Baraka underground to Havana". In Kali Argyriadis; Giulia Bonacci; Adrien Delmas (eds.). Cuba and Africa, 1959–1994: Writing an alternative Atlantic history. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. pp. 161–182. ISBN 978-1-77614-633-8.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2010). Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era (5th ed.). Dar Es Salaam and Pretoria: New Africa Press. ISBN 0-9802534-1-1.

- O'Ballance, Edgar (1999). The Congo-Zaire Experience, 1960–98 (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 9780230286481.

- Onoma, Ato Kwamena (2013). Anti-Refugee Violence and African Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03669-7.

- Prunier, Gérard (2009). Africa's World War : Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-970583-2.

- Stapleton, Tim (2017). "Refugee-warriors and other people's wars in post-colonial Africa: the experience of Rwandese and South African military exiles (1960–94)". In Falola, Toyin; Mbah, Emmanuel (eds.). Dissent, Protest and Dispute in Africa. New York City: Routledge. pp. 241–259. ISBN 978-1-138-22003-4.

- Thomas, Gerry S. (September 1986). "Waterborne Mercs. Sailing with the Infamous". Soldier of Fortune. 11 (9). Soldier of Fortune: 60–61, 82–86.

- Turner, Thomas (2007). The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth, and Reality (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-688-9.

- Villafana, Frank (2017) [1st pub. 2009]. Cold War in the Congo: The Confrontation of Cuban Military Forces, 1960–1967. Abingdon; New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4128-4766-7.