Nieuport IV

| Nieuport IV | |

|---|---|

| |

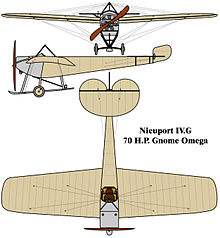

| Nieuport IV.G of the Air Battalion Royal Engineers | |

| Role | Sporting and military monoplane |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Nieuport |

| First flight | 1911 |

| Introduction | 1911 |

| Status | retired |

| Primary users | Imperial Russian Air Service Aéronautique Militaire Corpo Aeronautico Militare |

| Produced | 1911–1915 |

| Developed from | Nieuport III |

| Variants | Nieuport VI |

The Nieuport IV was a French-built sporting, training and reconnaissance monoplane of the early 1910s.

Design and development

[edit]Societe Anonyme des Etablissements Nieuport was formed in 1909 by Édouard Nieuport. The Nieuport IV was a development of the single-seat Nieuport II and two seat Nieuport III.A. It was initially designed as a two-seat sporting and racing monoplane, but was also bought by the air forces of several countries. It was initially powered by a 50 hp (37 kW) Gnome Omega rotary engine, which was later replaced by more powerful rotaries.[1]

Operational history

[edit]The first Nieuport IVs were built in 1911 and production continued well into World War I in Russia.[2] The design was adopted in small numbers by most air arms of the period, although the Imperial Russian Air Service was the largest user.

The IV.G was one of the principal aircraft used by the Imperial Russian Air Service during its formative years, with roughly 300 being produced locally by the Russo-Baltic Wagon Works and Shchetinin in St. Petersburg, and the Dux Factory in Moscow.[3] Lt. Pyotr Nesterov performed the first ever loop, over Kiev in a model IV.G on 27 August 1913 for which he was placed under arrest for 10 days for "undue risk to government property" until the feat was repeated in France by Adolphe Pégoud; Nesterov was then awarded a medal and a promotion.[4]

The French government equipped a single squadron with Nieuport IV.Ms, Escadrille N12 initially based at Reims, having purchased at least 10. This unit continued to operate Nieuport monoplanes after the start of World War I, slowly replacing them with other types as attrition reduced their numbers.[5]

The Swedish Air Force was presented with a IV.G in 1912 by four individuals, becoming one of the first aircraft of that force,[1] which was later joined by a second IV.G in 1913, and a IV.H transferred from the Swedish Navy.[6]

The Japanese Army operated one IV.G and one IV.M, which were designated as Army Nieuport NG2 aeroplane and Army Nieuport NM aeroplane respectively,[7] with the NG being flown in the Tsingtao campaign in September and October 1914 alongside four Maurice Farman MF.11s.[8]

One of the first batch of aircraft purchased by the British Army's Air Battalion Royal Engineers (the precursor to the Royal Flying Corps) was a Nieuport IV.G and serialed B4. Additional IV.G monoplanes were purchased from private individuals including one from Claude Grahame-White and another from Charles Rumney Samson, plus three others.[9][10] The Nieuport IVs were in service when the RFC carried out an investigation into monoplane crashes. While this report covered an accident involving a Nieuport IV, it determined the accident to be a result of improper maintenance which lead to engine failure, rather than a structural failure such as with the Bristol monoplane and Deperdussin monoplane whose structural deficiencies led to the Monoplane Ban.[11]

Argentina purchased a single IV.G named la Argentina which served with the Escuela de Aviation Militaire.[12]

In Greece, a IV.G was bought privately and named Alkyon. After being the first aircraft to fly in Greece, it was resold to the government which used it during the First Balkan War in 1912, flying from Larissa.[12]

Siam purchased 4 IV.Gs which were used as trainers at Don Muang airfield.[13]

Spain purchased one IV.G and 4 IV.Ms which were used by the Escuela Nieuport de Pau for training before 3 were transferred to an operational school (Escuela) at Tetuán, (Spanish Morocco) which then moved to Zeluán, remaining operational until 1917.[6]

Italy's 1st Flottiglia Aeroplani of Tripoli operated several Nieuport IV.Gs during the Italo-Turkish War, one of which became the first aeroplane to be used in combat when it flew a reconnaissance mission against Turkish forces on 23 October 1911.[14] It narrowly missed out to a Bleriot XI with the same unit for the honor of being the first aircraft to drop a bomb on enemy forces. The pilot who carried out this mission, Capt. Maizo, also became one of the first victims of anti-aircraft fire when he was shot down by an Austrian cannon weeks before the war ended in 1912.[14]

First intercontinental flight

[edit]Two officers of the former Spanish Air Force, Emilio Herrera and José Ortiz Echagüe, Captains of the Corps of Engineers of the 1st Expeditionary Air Squadron, on February 14th, 1914, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in a Nieuport IV.M, a flight between Tetouan (Morocco) and Seville (Spain), being the first intercontinental flight of the aviation history.[15]

That day,[16] Captains Herrera and Ortiz Echagüe took off from Tetouan, then the capital of the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco, at 1:30 p.m. and landed at Tablada Aerodrome (Seville) shortly after 6 p.m., thus taking almost 5 hours to cover the 208 kilometers in a straight line that separate the two cities. For the first time in history, an aeroplane crossed the Strait of Gibraltar, and for the first time an intercontinental flight was also made.

Despite not being a very long flight, they had to face numerous difficulties. The worst thing was the strong winds blowing in the Strait of Gibraltar, considering the limitations of their Nieuport IV-M (80-horsepower Gnome engine). The opposition of the Riffian tribesmen to the Protectorate in the form of continuous attacks to the spaniards (wich will end in the Rif War) was another element of danger. Also British government, prohibited the two pilots flying over Gibraltar.

The aviators, on leaving Tetouan, had to fly along the Martín River to its mouth, flying at a height of only 200 metres. Then they skirted the African coast until they reached Ceuta, where they raised the aircraft to almost 2,000 metres. At this height they crossed the strait whipped by a strong easterly wind. After entering the peninsula and rising a little higher to clear the mountains, they sighted Jerez, and from there headed for Seville, where they entered following the line of the Guadalquivir.

At the Tablada Aerodrome His Majesty King Alfonso XIII was waiting for them, to whom they delivered a message from the High Commissioner of Spain in Morocco. It was one of the first milestones of Spanish aviation, which in the following decade would experience its golden age with the great air raids.

Variants

[edit]- IV

- Generic base designation (specific aircraft always had an applicable suffix letter)

- IV.G

- Gnome basic sport/racing model with various sizes of Gnome rotary from 50 to 100 hp (37 to 75 kW)

- IV.H

- Hydro floatplane fitted with two main floats and a tail float – used extensively for competition with engines of up to 200 hp

- IV.M

- Enlarged Military observation variant with various Gnome rotaries from 70 to 100 hp (52 to 75 kW) – designed to be readily assembled and disassembled for transport by truck

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

The Swedish Air Force maintained their first model IV in airworthy condition until 1965.[17] This aircraft is now preserved in the Flygvapenmuseum at Malmen near Linköping.[18] The Museo del Aire at Cuatro Vientos near Madrid has a full-scale replica of one of their model IVs.[19]

Operators

[edit]Military

[edit]Specifications (IVM)

[edit]

Data from Aviafrance

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Capacity: 1 passenger

- Length: 8.2 m (26 ft 11 in)

- Wingspan: 12.1 m (39 ft 8 in)

- Wing area: 22.0 m2 (237 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 483 kg (1,065 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Gnome rotary piston, 75 kW (100 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed

Performance

- Maximum speed: 120 km/h (75 mph, 65 kn)

- Time to altitude: 12 minutes 40 seconds to 500m

See also

[edit]Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Bleriot XI

- Bristol Coanda Monoplanes

- Deperdussin TT

- Etrich Taube

- Gabardini monoplane

- Hanriot D.I

- LVG E.I (developed copy of Nieuport IV)

- Morane-Saulnier G

- REP Type N

Related lists

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Green, 1965, p.347

- ^ Sanger, 2002, p.109-111

- ^ Davilla, 1997 p.351

- ^ Durkota, 1997, pp.201–204

- ^ Sanger, 2002, p.77

- ^ a b Sanger, 2002, p.157

- ^ "Brief history of the Nieuport monoplane". Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Francillon, 1979, p.48

- ^ Sanger, 2002, p.93-95

- ^ Robertson, 1979, p.18

- ^ Spooner, Stanley, ed. (1913). "Army Monoplanes Report". Flight Magazine. Vol. 5, no. 215. pp. 154–158.

- ^ a b c Sanger, 2002, p.154

- ^ Sanger, 2002, p.156

- ^ a b Sanger, 2002, p.131

- ^ Palma, Raúl José Martín (2024-08-15). "Cuando militares españoles protagonizaron el primer vuelo de la historia entre África y Europa". El Debate (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ "Ejército del Aire - Cultura Aeronáutica - Rincón del Aviador". ejercitodelaire.defensa.gob.es. Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ Green, 1965 p.346

- ^ Ogden, 2006, p.484

- ^ Ogden, 2006, p.470

- ^ "Nieuport Monoplane WW I Period TUAF Aircraft 1 nci dunya savasi dönemi Turk HvKK Ucaklari". tayyareci.com.

- ^ Dan Antoniu (2014). Illustrated History of Romanian Aeronautics. p. 31. ISBN 978-9730172096.

References

[edit]- Davilla, Dr. James J.; Soltan, Arthur M. (1997). French Aircraft of the First World War. Stratford, CT: Flying Machines Press. ISBN 978-0-9637110-4-5.

- Durkota, Alan; Darcey, Thomas; Kulikov, Victor (1995). The Imperial Russian Air Service — Famous Pilots and Aircraft of World War I. Mountain View, CA: Flying Machines Press. pp. 201–204. ISBN 978-0-9637110-2-1.

- Francillon, René J. (1979). Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0370302515.

- Green, William (1965). The Aircraft of the World. Macdonald & Co (Publishers) Ltd.

- Ogden, Bob (2006). Aviation Museums and Collections of Mainland Europe. Air-Britain (Historian) Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85130-375-8.

- Pommier, Gerard (2002). Nieuport 1875–1911 — A biography of Edouard Nieuport. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-1624-1.

- Robertson, Bruce (1979). British Military Aircraft Serials 1911–1979. Cambridge: Patrick Stevens. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-85059-360-0.

- Rozendaal, John (31 August 1912). "Der Nieuport-Eindekker (part 1)". Zeitschrift für Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt (in German). 3 (16): 211–213.

- Rozendaal, John (14 December 1912). "Der Nieuport-Eindekker (part 2)". Zeitschrift für Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt (in German). 3 (23): 300–303.

- Sanger, Ray (2002). Nieuport Aircraft of World War One. Wiltshire: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-86126-447-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Hartmann, Gérard. "Le grand concours d'aviation militaire de Reims 1911" [The Reims Military Aviation Competition, 1911] (PDF). Dossiers historiques et techniques aéronautique française (in French). Gérard Hartmann. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Moulin, Jean (October 2004). "Reims 1911, le premier concours d'appareils militaires au monde!" [Reims 1911, the First Military Aircraft Concours in the World!]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (139): 51–58. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Opdycke, Leonard E. (1999). French Aeroplanes before the Great War. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-7643-0752-5.