Nevado Sajama

| Nevado Sajama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 6,542 m (21,463 ft) |

| Listing | Country high point Ultra |

| Coordinates | 18°06′29″S 68°52′59″W / 18.10806°S 68.88306°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Aymara chak xaña, "west"[2] |

| Native name | Chak Xaña (Aymara) |

| Geography | |

| Country | Bolivia |

| Department | Oruro Department |

| Parent range | Cordillera Occidental (Andes) |

Nevado Sajama ([neˈβaðo saˈxama]; Aymara: Chak Xaña) is an extinct volcano and the highest peak in Bolivia. The mountain is located in Sajama Province, in Oruro Department. It is situated in Sajama National Park and is a composite volcano consisting of a stratovolcano on top of several lava domes. It is not clear when it erupted last but it may have been during the Pleistocene or Holocene.

The mountain is covered by an ice cap, and Polylepis tarapacana trees occur up to 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) elevation.

Geography and geomorphology

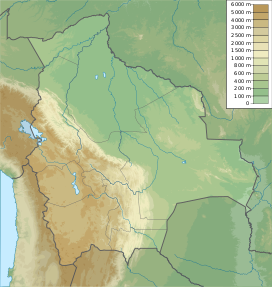

[edit]Nevado Sajama is located in the Sajama Province of the Oruro Department in Bolivia,[3] about 18.6 kilometres (11.6 mi) from the border with Chile. Cholcani volcano lies southeast of Sajama,[4] and another neighbouring volcano, Pomerape, resembles Sajama in its appearance.[5] A road runs along the southeastern flank of the volcano, with additional roads completing a circle around Sajama. The village of Sajama lies on its western foot, with the village of Caripe to the northeast of the mountain and Lagunas to the southwest, and there are a number of farms.[6]

In Bolivia, the Andes mountain chain splits into two branches separated by a 3,500–4,000 metres (11,500–13,100 ft) high plateau, the Altiplano. Nevado Sajama lies in the Western Andes of Bolivia[7] and in the western side of the Altiplano;[8] more specifically the mountain is located before the Western Cordillera.[9]

Nevado Sajama rises about 2.2 kilometres (1.4 mi) from the surrounding terrain to a height of 6,542 metres (21,463 ft) (earlier estimates of its height are 6,572 metres (21,562 ft)[10]),[4] making it the highest mountain of Bolivia.[11] Below 4,200 metres (13,800 ft) the mountain is characterized by parasitic vents and a cover of lava fragments and volcanic ash.[9] Two secondary summits 5,031 metres (16,506 ft) and 5,161 metres (16,932 ft) occur west and east-northeast from Sajama respectively; the former is named Cerro Huisalla[12] and the second is Huayna Potosi.[13] The mountain has a conical shape and is capped by a summit crater[5] that, owing to its ice fill, appears to be linked to the flat summit plateau of Sajama[14] but other records do not indicate the presence of a crater.[10] The Patokho, Huaqui Jihuata and Phajokhoni valleys are located on the eastern flank;[15] at lower elevations the whole volcano features glacially deepened valleys.[9]

The terrain is characterized by a continuous ice cover in the central sector of the mountain, exposures of bedrock, deposits and rock glaciers in some sites, alluvial fans and scree in the periphery of Sajama and moraines forming a girdle around the upper sector of Sajama.[16] The ground moraines are the most prominent moraines on Sajama, and have varying colours depending on the source of their component rocks. Vegetation and small lakes occur in their proximity, while other parts are unvegetated. They mostly occur within glacial valleys, but some appear to have formed underneath small plateau ice caps on flatter terrain.[17] At lower elevations the glaciers lead to lava flows and matorral and tolar vegetation, and finally to grassland at lower altitudes.[18]

A number of wetlands called bofedales occur on the mountain.[13] Starting in the lake Laguna Huana Kkota on the northwestern foot of Sajama, the Tomarapi River flows first northeastward, then east, south and southeast around the northern and eastern flanks of the volcano; the Sicuyani River, which originates on Sajama, joins it there. The southern flanks give rise to the Huaythana River, which flows directly south and then makes a sharp turn to the east. The Sajama River originates on the western side of the volcano, flowing due south and increasingly turning southeast before joining the Lauca River.[12][10] The other rivers draining Sajama and its ice cap also eventually join the Lauca River and end in the Salar de Coipasa.[19]

Geology

[edit]

Nevado Sajama is part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, where volcanism is triggered by the subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South America Plate.[3] Changes in the subduction regime took place during the Oligocene and directed an increase of volcanic activity in the region.[20] Volcanoes in the region have ages ranging from Pleistocene to Miocene[16] and grew on top of earlier ignimbrites; the whole volcanic activity was controlled by faults.[21]

The mountain is a stratovolcano located atop several lava domes. The stratovolcano consists of lava flows and pyroclastic material that radiate away from the centre of the volcano.[5] Some parasitic vents occur southeast of Sajama[4] and have produced lava domes and lava flows. The parasitic vents away from the volcano are older[22] and their location appears to be controlled by radial dikes;[23] the whole complex is a compound volcano. Two later volcanic units are known as the Colquen Wilqui lavas and the Jacha Khala tuff.[3] The Sajama volcano rises within a caldera that has been buried by later volcanic activity so that it is only recognizable on its eastern-northeastern side.[24] A circular structure around Sajama may be the origin of the 2.7 million years old Lauca-Perez Ignimbrite.[25]

Argon-argon dating has yielded ages of 679,000 years ago from Sajama[26] and of 80,900 to 25,000 years ago for the Kkota Kkotani lavas, which are unrelated to the main Sajama volcano.[3] The date of the last eruption is not known, it may have occurred in the Pleistocene or Holocene.[4] Hot springs occur on the Junthuma River and reflect the presence of geothermal heat with temperatures of about 250–230 °C (482–446 °F)[21] on the western foot of Sajama,[27] and volcanic rocks of Sajama bear traces of fumarolic activity.[28]

Three major geologic lineaments occur in the region, the north-northwesterly trending Sajama lineament, a west-southwesterly one aligned with high topographical features and a west-northwesterly one. The west-southwesterly one played an important role in the development of Sajama volcano.[3]

Composition

[edit]The volcano has erupted rocks ranging from andesite to rhyodacite, with the main stratovolcano formed by andesites[4] that contain hornblende and pyroxene[5] and phenocrysts of augite, biotite, iron oxide, olivine, orthopyroxene, pargasite, plagioclase, quartz and titanium oxide.[29] Deposits of copper, gold, lead, silver and sulfur were reported as well.[10] The volcanic rocks erupted by Sajama define a potassium-rich calc-alkaline suite and formed through various processes, including assimilation of country rock, fractional crystallization and magma mixing (particularly in the Sayara lavas).[3]

Climate

[edit]At Cosapa on the foot of Sajama, annual mean temperatures are about 7.3 °C (45.1 °F)[16] while the town of Sajama sees annual temperatures of 4.3 °C (39.7 °F); precipitation there is about 327 millimetres per year (12.9 in/year). The daily temperature range approaches 40 °C (72 °F) there.[30]

Sajama is located between two climate regimes, a westerly one characterized by a dry climate and the Southeast Pacific High and an easterly one with a moister atmosphere. During the southern hemisphere summer, easterly winds carry moist air towards Sajama where solar insolation then triggers showers and thunderstorms;[11] the moisture ultimately originates in the Atlantic Ocean.[16] During winter, dry westerly winds prevail although cold air outbreaks from the westerlies belt sometimes trigger intense snowfall[31] which is often underestimated by precipitation data.[32] Overall, on the Altiplano precipitation diminishes from the northeast to the southwest.[8]

Summer precipitation is typically reduced during El Nino years,[33] but on Nevado Sajama there is little correlation.[34]

Vegetation and animals

[edit]While the vegetation of the surroundings of Sajama is considered to be a dry grassland known as puna, on the mountain itself there is some vertical gradation. Below 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) shrubs such as asteraceae, cactaceae, fabaceae and solanaceae dominate the vegetation. Between 4,000–4,800 metres (13,100–15,700 ft) the last three families become less important. Here especially during the wet season poaceae grasses become more important; finally above 4,800 metres (15,700 ft) frost-tolerant herbs such as Azorella and asteraceae, caryophyllaceae, malvaceae and poaceae make up most of the vegetation.[8] In depressions or places where water occurs, peat bogs called bofedales develop. Taxa that occur here include apiaceae, cyperaceae, Azolla, Distichia and Plantago.[8] Animals include birds, vicuñas, vizcachas and mice;[18] the latter occur up to 5,221 metres (17,129 ft) elevatn.[35]

Nevado Sajama features the highest treeline on Earth at 5,200 metres (17,100 ft) elevation,[35] as Polylepis tarapacana forms woodlands[8] that have both a sharp upper and a sharp lower limit on the mountain.[9] The trees are usually no higher than 5 metres (16 ft) and are separated by large distances from each other and appear to localize to spots where water is available.[36] The current woods are remnants; whether the decrease is caused by human impact or climate change is not clear.[8] Protecting these woodlands was the impetus for the 1939 creation of the Sajama National Park.[37]

Glaciers

[edit]

Above 5,600 metres (18,400 ft), Sajama is extensively glaciated.[4] It is among the southernmost mountains in the region with significant glaciers; farther south the atmosphere is too dry to permit the development of glaciers.[16] Two ice cores were taken from the summit area in 1997,[8] preceded by a religious ceremony, as the local Aymara people feared that the mountain deities would be angered by the drilling otherwise.[38] Rock glaciers also occur above the zero degree isotherm above 4,800 metres (15,700 ft), such as on lateral peaks.[39] Meltwater from the glaciers partially seeps underground and only reappears away from the volcano.[40]

Sajama and neighbouring mountains featured much larger glaciers in the past.[41] The history of glaciation on Sajama in general is poorly known,[15] but it appears that the outermost glacial features originated during the late last glacial maximum and the intermediary features during the Middle Holocene which is usually considered to be a warm and dry period in the region.[42]

Human interactions

[edit]Sajama is a sacred mountain for the regional communities,[43] and a number of oral traditions record beliefs involving Sajama.[44] In one myth, Sajama is the head of the Mururata mountain after the latter was decapitated by Illimani mountain, both in the Eastern Cordillera.[45] Other mythologies assert that the Nevados de Payachata (Pomerape and Parinacota) are the children of Sajama and Anallaxchi.[46] In another local belief, Tacora and Sajama were two mountains in competition for two women (the Nevados de Payachata). Depending on the specific myth either the two women drove Tacora off and removed the top of the mountain, or Sajama did and injured Tacora; Tacora subsequently fled, shedding blood and a piece of its heart.[47]

There are a number of archaeological sites on the mountain, including chullpa burials and pukara fortifications, distributed over various altitudes and connected through paths.[43] About 40 such sites have been found, most of them at low elevations[48] on the western and northern foot of Sajama.[49] Some of these sites have yielded ceramics. The archaeological sites demonstrate a direct link between the mountain and their builders and with the resolution of local conflicts.[50]

During the second undisputed ascent on the mountain in 1946, one mountaineer disappeared and his body was never found.[51] In August 2001, two teams of Sajama villagers and Bolivian mountain guides played a football match on top of Mount Sajama in an effort to show that altitude itself is not a limitation to physical strain.[52] In 2015, a challenge to hold a political debate on the summit of Sajama was made by a candidate to an election.[53] The 50-boliviano Bolivian banknote launched in October 2018 shows Sajama on its reverse.[54]

See also

[edit]- Asu Asuni

- Jach'a Kunturiri

- K'isi K'isini

- Llisa

- Pomerape

- Sajama Lines

- Waña Quta

- List of volcanoes in Bolivia

References

[edit]- ^ cf. OSM or Bing Maps or Google Maps for coordinates

- ^ Tenorio Villegas, Celia; Ajacopa Pairumani, Sotero (2012). EL LÉXICO RITUAL DE LA WAXT'A EN AYMARA DE WARAQ'U APACHETA Y CHHUCHHULAYA DE LA TERCERA SECCIÓN DEL MUNICIPIO DE ACHOCALLA DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE LA PAZ (Thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Carrera de Lingüística e Idiomas. p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Galarza, Mauri, Iris Marcela (2004). "Geología y petrología del volcán Sajama: Provincia Sajama, departamento de Oruro" (in Spanish). La Paz: Higher University of San Andrés. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Nevado del Sajama". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b c d Ferrán, O. González (1995). Volcanes de Chile (in Spanish). Instituto Geográfico Militar. p. 109. ISBN 9789562020541.

- ^ Hoffmann, Dirk (February 2007). "The Sajama National Park in Bolivia". Mountain Research and Development. 27 (1): 12. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2007)27[11:TSNPIB]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 140194055.

- ^ Vuille 1999, p. 1579.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reese, C. A.; Liu, K. B.; Thompson, L. G. (2013). "An ice-core pollen record showing vegetation response to Late-glacial and Holocene climate changes at Nevado Sajama, Bolivia". Annals of Glaciology. 54 (63): 183–190. Bibcode:2013AnGla..54..183R. doi:10.3189/2013AoG63A375. ISSN 0260-3055.

- ^ a b c d Jordan 1980, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d Blanco, Pedro Aniceto (1904). Diccionario geográfico del departamento de Oruro [1904] (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos ; Lima. p. 84. ISBN 9789990553444.

- ^ a b Vuille 1999, p. 1580.

- ^ a b Defense Mapping Agency (1996). "Nevado Sajama, Bolivia; Chile" (Map). Latin America, Joint Operations Graphic (1 ed.). 1:250000.

- ^ a b "NEVADO SAJAMA, BOLIVIA 5839-IV H731 EDICION 1-IGM" (PDF). IGM Bolivia (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Ahlfeld, F; Branisa, L (1960). Geologia de Bolivia. Boliviano Petróleo. pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Smith, Lowell & Caffee 2009, p. 362.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Lowell & Caffee 2009, p. 361.

- ^ Smith, Lowell & Caffee 2009, pp. 363–365.

- ^ a b Cruz 2023, p. 78.

- ^ Javier & Rafael 2011, p. 168.

- ^ Javier & Rafael 2011, p. 163.

- ^ a b International Atomic Energy Agency 1992, p. 142.

- ^ Nakada, Setsuya (1 April 1991). "Magmatic processes in titanite-bearing dacites, central Andes of Chile and Bolivia". American Mineralogist. 76 (3–4): 548. ISSN 0003-004X.

- ^ Brockmann 1973, p. 5.

- ^ Brockmann 1973, p. 6.

- ^ Watts, Robert B.; Clavero Ribes, Jorge; Sparks, J.; Stephen, R. (2014). "Origen y emplazamiento del Domo Tinto, volcán Guallatiri, Norte de Chile". Andean Geology. 41 (3): 558–588. doi:10.5027/andgeoV41n3-a04. ISSN 0718-7106. Archived from the original on 2018-10-29. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- ^ Jiménez, Néstor; López-Velásquez, Shirley; Santiváñez, Reynaldo (October 2009). "Evolución tectonomagmática de los Andes bolivianos". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 65 (1): 036–067. ISSN 0004-4822. Archived from the original on 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

- ^ International Atomic Energy Agency 1992, p. 149.

- ^ International Atomic Energy Agency 1992, p. 144.

- ^ Xirouchakis, Dimitrios; Lindsley, Donald H.; Frost, B. Ronald (March 2001). "Assemblages with titanite (CaTiOSiO4), Ca-Mg-Fe olivine and pyroxenes, Fe-Mg-Ti oxides, and quartz: Part II. Application". American Mineralogist. 86 (3): 259. Bibcode:2001AmMin..86..254X. doi:10.2138/am-2001-2-307. ISSN 0003-004X. S2CID 132673481. Archived from the original on 2018-10-29. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- ^ Javier & Rafael 2011, p. 165.

- ^ Vuille 1999, p. 1581.

- ^ Vuille 1999, p. 1582.

- ^ Vuille 1999, p. 1598.

- ^ Vuille 1999, p. 1599.

- ^ a b Storz et al. 2024, p. 733.

- ^ Jordan 1980, p. 304.

- ^ "ÁREAS PROTEGIDAS SUBNACIONALES EN BOLIVIA SITUACION ACTUAL 2012" (PDF). Dirección General de Biodiversidad y Áreas Protegidas (in Spanish). 2012. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Krajick, Kevin (18 October 2002). "Ice Man: Lonnie Thompson Scales the Peaks for Science". Science. 298 (5593): 518–22. doi:10.1126/science.298.5593.518. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12386311. S2CID 37237853.

- ^ Smith, Lowell & Caffee 2009, p. 365.

- ^ Jenny, B.; Kammer, K.; Ammann, C. (1996). Climate Change in den trockenen Anden (in German). Geographia Bernensia. ISBN 3906151034.

- ^ Javier & Rafael 2011, p. 166.

- ^ Smith, Lowell & Caffee 2009, pp. 368, 371.

- ^ a b Cruz 2023, p. 77.

- ^ Alavi Mamani 2009, p. 134.

- ^ Ceruti, María Constanza (2013). "Mismi y Huarancante: nevados sagrados del Valle de Colca". Anuario de Arqueología, Rosario (2013), 5: 353. Archived from the original on 2018-10-29. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ Alavi Mamani 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Reinhard, Johan (2002). "A high altitude archaeological survey in northern Chile". Chungará (Arica). 34 (1): 85–99. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562002000100005. ISSN 0717-7356.

- ^ Cruz 2023, p. 81.

- ^ Cruz 2023, p. 82.

- ^ Cruz 2023, p. 105.

- ^ 1998 American Alpine Journal. The Mountaineers Books. p. 263. ISBN 9781933056456.

- ^ Enever, Andrew (7 August 2001). "Bolivian footballers reach new high". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- ^ "Candidato boliviano reta a sus rivales a debatir en la cima de un nevado". Pulso Diario de San Luis. AP. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "El Banco Central de Bolivia lanza a la circulación el nuevo billete de Bs50" (in Spanish). Banco Central de Bolivia. 26 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Alavi Mamani, Zacarias (May 2009). Una aproximación a las toponimias del Poopó y del Desaguadero (Report) (in Spanish).

- Brockmann, C.E. (1973). "Sketch on the structural geology and vulcanism in the Central High Plateau of the Bolivian Andes". NASA Technical Reports Server (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Cruz, Ramón Torrez (23 March 2023). "Áreas de encuentro ritual y convivencia pacífica, en torno a la deidad de la montaña Sajama durante el periodo intermedio tardío (1000 – 1450 d.c.)". Revista Patrimonio y Arqueología (in Spanish) (1): 75–107. ISSN 2959-2410.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (1992). "Geothermal investigations with isotope and geochemical techniques in Latin America".

- Javier, Santa Cecilia Mateos, Fernando; Rafael, Mata Olmo (2011-01-01). "Caracterización físiográfica de la Puna de Sajama, cordillera occidental de los Andes (Bolivia) = Puna Physiographic Characterization of Sajama (West Of The Andes Mountains)". Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie VI, Geografía (4–5): 159. doi:10.5944/etfvi.4-5.2011.13728.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jordan, E. (1980). "Das durch Wärmemangel und Trockenheit begrenzte Auftreten von Polylepis am Sajama Boliviens mit dem höchsten Polylepis-Gebüschvorkommen der Erde". Deutsch. Geographentag (in German) (42): 303–305.

- Smith, Colby A.; Lowell, Thomas V.; Caffee, Marc W. (May 2009). "Lateglacial and Holocene cosmogenic surface exposure age glacial chronology and geomorphological evidence for the presence of cold-based glaciers at Nevado Sajama, Bolivia". Journal of Quaternary Science. 24 (4): 360–372. Bibcode:2009JQS....24..360S. doi:10.1002/jqs.1239. ISSN 0267-8179. S2CID 128543043.

- Storz, Jay F.; Quiroga-Carmona, Marcial; Liphardt, Schuyler; Herrera, Nathanael D.; Bautista, Naim M.; Opazo, Juan C.; Rico-Cernohorska, Adriana; Salazar-Bravo, Jorge; Good, Jeffrey M.; D’Elía, Guillermo (1 June 2024). "Extreme High-Elevation Mammal Surveys Reveal Unexpectedly High Upper Range Limits of Andean Mice". The American Naturalist. 203 (6): 726–735. doi:10.1086/729513. PMC 10473662.

- Vuille, M. (30 November 1999). "Atmospheric circulation over the Bolivian Altiplano during dry and wet periods and extreme phases of the Southern Oscillation". International Journal of Climatology. 19 (14): 1579–1600. Bibcode:1999IJCli..19.1579V. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0088(19991130)19:14<1579::AID-JOC441>3.0.CO;2-N. S2CID 18599470.

Bibliography

[edit]- Biggar, John (2020). The Andes: A Guide for Climbers and Skiers (5 ed.). Scotland: Andes Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9536087-6-8.

- Darack, Ed (2001). Wild Winds: Adventures in the Highest Andes. Cordee / DPP. ISBN 978-1884980817.

External links

[edit]- Climbing Sajama and Illimani

- "Nevado Sajama". Peakware.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Detailed description of the volcano