Constant Lambert

Constant Lambert | |

|---|---|

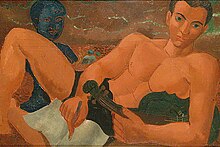

Portrait by Christopher Wood (1926) | |

| Born | Leonard Constant Lambert 23 August 1905 Fulham, London, England |

| Died | 21 August 1951 (aged 45) London, England |

| Education | Royal College of Music Christ's Hospital |

| Known for | Composer conductor author |

| Notable work | The Rio Grande Summer's Last Will and Testament Music Ho! |

| Spouse(s) |

Florence Kaye

(m. 1931; div. 1947) |

| Partner | Margot Fonteyn |

| Father | George Lambert |

| Relatives | Kit Lambert (son) Maurice Lambert (brother) |

Leonard Constant Lambert (23 August 1905 – 21 August 1951) was a British composer, conductor, and author. He was the founder and music director of the Royal Ballet, and (alongside Dame Ninette de Valois and Sir Frederick Ashton) he was a major figure in the establishment of the English ballet as a significant artistic movement.[1]

His ballet commitments, including extensive conducting work throughout his life, restricted his compositional activities. However one work, The Rio Grande, for chorus, orchestra and piano soloist, achieved widespread popularity in the 1920s, and is still regularly performed today. His other work includes a jazz influenced Piano Concerto (1931), major ballet scores such as Horoscope (1937) and a full-scale choral masque Summer's Last Will and Testament (1936) that some consider his masterpiece.

Lambert had wide-ranging interests beyond music, as can be seen from his critical study Music Ho! (1934), which places music in the context of the other arts. His friends included John Maynard Keynes, Anthony Powell and the Sitwells.[2] To Keynes, Lambert was perhaps the most brilliant man he had ever met; to de Valois he was the greatest ballet conductor and advisor his country had ever had; to the composer Denis ApIvor he was the most entertaining personality of the musical world.[3]

Early life and music

[edit]

The son of Australian painter George Lambert and his wife Amy, and the younger brother of Maurice Lambert, Constant Lambert was educated at Christ's Hospital near Horsham in West Sussex. While still a boy he demonstrated formidable musical gifts, and wrote his first orchestral work at the age of 13. In September 1922 Lambert entered the Royal College of Music, where his teachers were Ralph Vaughan Williams, R. O. Morris and Sir George Dyson (composition), Malcolm Sargent (conducting) and Herbert Fryer (piano).[4] His contemporaries there included the pianist Angus Morrison, conductor Guy Warrack, Thomas Armstrong (a future head of the Royal Academy of Music), and the composers Gavin Gordon, Patrick Hadley and Gordon Jacob.[5]

In 1925 (at the age of 20) he received a high profile commission to write a ballet for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (Roméo et Juliette, 1926, choreographed by Nijinska). For a few years he enjoyed celebrity, through the broader success of his next ballet (the neo-classical Pomona of 1927, choreographed again by Nijinska), and through his participation as narrator in many public performances (and a recording) of William Walton and Edith Sitwell's controversial Façade.[6]

Jazz influence

[edit]Lambert's best-known composition followed. The Rio Grande (1927), for piano and alto soloists, chorus, and orchestra of brass, strings and percussion, sets a poem by Sacheverell Sitwell. It achieved considerable success, and Lambert made two recordings of the piece as conductor (1930 and 1949). He had a great interest in African-American music, and once said that he would have ideally liked The Rio Grande to feature a black choir.[7] He held a very positive view of jazz rhythms and their incorporation in classical music saying once that:

"The chief interest of jazz rhythms lies in their application to the setting of words, and although jazz settings have by no means the flexibility or subtlety of the early seventeenth-century airs, for example, there is no denying their lightness and ingenuity … English words demand for their successful musical treatment an infinitely more varied and syncopated rhythm than is to be found in the nineteenth-century romantics, and the best jazz songs of today are, in fact, nearer in their methods to the late fifteenth-century composers than any music since."[8]

Lambert was to take his interest in jazz much further in works such as the Piano Sonata (1929) and the Concerto for piano and nine Instruments (1931), where the style moves away from the "symphonic jazz" of Gershwin and Paul Whiteman to something much more tense and urban, with popular and formal elements of composition closely integrated, rhythms jagged and extreme, and harmony sometimes approaching atonalism.[9] The second movement of the Sonata features a blues in rondo form.[10] The Concerto's unusual chamber scoring becomes something of a hybrid between a jazz band and the ensemble used in Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire.[11]

Later career

[edit]

Lambert was appointed in 1931 as conductor and music director of the Vic-Wells ballet (later The Royal Ballet),[1] but his career as a composer stagnated. His major choral work Summer's Last Will and Testament (1935, after the play of the same name by Thomas Nashe), one of his most emotionally dark works, proved unfashionable in the mood following the death of King George V, but Alan Frank hailed it at the time as Lambert's "finest work".[12]

The Second World War took its toll on his vitality and creativity. He was ruled unfit for active service in the armed forces; decades of hard drinking had impaired his health, which declined further with the development of diabetes that remained undiagnosed and untreated until very late in his life. Lambert's childhood experiences (which included a near-fatal bout of septicaemia) had given him a lifelong detestation and fear of the medical profession.

Lambert himself considered he had failed as a composer, and completed only two major works after the disappointment of Summer's Last Will and Testament - they were the ballet scores Horoscope (1938) and Tiresias (1951) - though there were also several smaller works, such as the white-note piano four hands suite Trois pièces nègres pour les touches blanches, written for the identical twin piano duo Mary and Geraldine Peppin.[13] Instead he concentrated mostly on conducting, working closely with the Royal Ballet until his resignation in 1947. He continued to be featured as a guest conductor until shortly before his death in 1951.[1]

Broader cultural interests

[edit]An expert on painting, sculpture, and literature as well as music,[14] Lambert differed from most of his fellow English composers of the time in his perception of the importance of jazz. He responded positively to the music of Duke Ellington. His embrace of music outside the 'serious' repertoire is illustrated by his book Music Ho! (1934),[15] subtitled "a study of music in decline", which remains one of the wittiest, if most highly opinionated, volumes of music criticism in the English language.

Lambert's father, while born in Russia and of American heritage, viewed himself as first and foremost an Australian. Constant was always conscious of his Australian connections, although he never visited that country. For the first performance of his Piano Concerto (1931), rather than select a British-born pianist, Lambert chose the Sydney-born, Brisbane-trained Arthur Benjamin to play the solo part. Despite his disapproval of homosexuality he formed a good working relationship with Benjamin's fellow Australian Robert Helpmann. Afterwards he entrusted yet another Australian musician, Gordon Watson, with the task of playing the virtuoso piano part at the première of his last ballet, Tiresias.[16]

Personal life

[edit]

Lambert's first marriage was to Florence Kaye, on 5 August 1931;[17] their son was Kit Lambert, one of the managers of The Who, named after his friend the painter Christopher "Kit" Wood.[18] But he was soon engaged in an on-and-off affair with the ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn. According to friends of Fonteyn, Lambert was the great love of her life and she despaired when she finally realised he would never marry her. Some aspects of this relationship were symbolised in his ballet Horoscope (1938), in which Fonteyn was a principal dancer. After divorcing Kaye, in 1947 Lambert married the artist Isabel Delmer, who designed the stage sets and costumes for his ballet Tiresias; after his death, she married Alan Rawsthorne.[19] In 1945 Florence married Charles Edward Peter Hole; their daughter Anne later took the stage name Annie Lambert. During the 1930s Lambert also had a long affair and friendship with Laureen Goodare (mother of actress Cleo Sylvestre, Constant's goddaughter). Laureen was a dancer and cigarette girl at the Shim Sham Club in Wardour Street, Soho. Their affair lasted until his untimely death in 1951.

Close friends of his included Michael Ayrton, Sacheverell Sitwell and Anthony Powell. He was the prototype of the character Hugh Moreland in Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time, particularly in the fifth volume, Casanova's Chinese Restaurant, in which Moreland is a central character.[20]

Lambert died on 21 August 1951, two days short of his forty-sixth birthday, of pneumonia and undiagnosed diabetes complicated by acute alcoholism, and was buried in Brompton Cemetery, London. His son Kit was buried in the same grave in 1981.

Major works

[edit]Ballets

- Romeo and Juliet (1925)

- Pomona (1927)

- Horoscope (1938)

- Tiresias (1950)

Choral and vocal

- Eight poems of Li Po (1928)

- The Rio Grande (1927) (a setting of a poem by Sacheverell Sitwell)

- Summer's Last Will and Testament (1936; to words by Thomas Nashe)

- Dirge from Cymbeline (1947)

Orchestral

- The Bird Actors Overture (1924)

- Music for Orchestra (1927)

- Aubade héroïque (1941)

Chamber

- Concerto for piano, 2 trumpets, timpani and strings (1924)

- Concerto for piano and nine instruments (1931)

Instrumental

- Elegiac Blues (1927, orchestrated 1928)

- Piano Sonata (1930)

- Elegy, for piano (1938)

- Trois Pièces Nègres pour les Touches Blanches [Three Black Pieces for the White Keys], piano duet (4 hands) (1949)

Film music

- Merchant Seamen (semi-documentary; 1941)

- Anna Karenina (1948)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Constant Lambert biography". Royal Opera House. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Motion Andrew. The Lamberts. George, Constant and Kit (1996)

- ^ Constant Lambert – Beyond The Rio Grande by Stephen Lloyd, introduction

- ^ "Constant Lambert- Bio, Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music". www.naxos.com. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Lloyd, Stephen. Constant Lambert: Beyond the Rio Grande (2015) p 32

- ^ Driver, Paul (September 1980). "Façade Revisited". Tempo. New Series. 133/134 (133–134): 3–9. doi:10.1017/S0040298200031211. S2CID 251412618.

- ^ Palmer, Christopher (April 1971). "Constant Lambert: A Postscript". Music & Letters. 52 (2): 173–176. doi:10.1093/ml/LII.2.173.

- ^ "The Rio Grande (Lambert) - from CDH55388 - Hyperion Records - MP3 and Lossless downloads".

- ^ Hardy, Lisa. The British Piano Sonata, 1870-1945 (2012), pp. 129-140

- ^ Easterbrook, Giles. Notes to Hyperion CDH55937 (1995)

- ^ 'Lambert, Concerto for Piano and Nine Instruments', A Tune A Day

- ^ Frank, Alan (November 1937). "The Music of Constant Lambert". The Musical Times. 78 (1137): 941–945. doi:10.2307/923287. JSTOR 923287.

- ^ Motion Andrew. The Lamberts. George, Constant and Kit (1996)

- ^ Palmer, Christopher (April 1974). "Review of Constant Lambert by Richard Shead". Music & Letters. 55 (2): 241–242. doi:10.1093/ml/LV.2.241.

- ^ Lambert. Music Ho!. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ Graeme Skinner, musicologist Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Foss, Hubert (October 1951). "Constant Lambert, 23 August 1905–21 August 1951". The Musical Times. 92 (1304): 449–451.

- ^ Faulks, Sebastian (26 January 2010). The Fatal Englishman: Three Short Lives. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-5264-9.

- ^ Jacobi, Carol. Out of the Cage: The Art of Isabel Rawsthorne, London: The Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing, Feb 2021

- ^ Powell, Anthony: Memoirs, Vol 4, To Keep The Ball Rolling, 1976

Bibliography

[edit]- Drescher, Derek (producer). Remembering Constant Lambert, BBC Radio 3 documentary, broadcast 23 August 1975.

- Lloyd, Stephen. Constant Lambert: Beyond The Rio Grande. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-84383-898-2.

- McGrady, Richard. The Music of Constant Lambert. In Music & Letters Vol 51, No 3, July 1970

- Motion, Andrew. The Lamberts: George, Constant & Kit. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1986. ISBN 0-374-18283-3.

- Shead, Richard. Constant Lambert. London, 1972. ISBN 9780903620017.

External links

[edit]- Works by Constant Lambert at Faded Page (Canada)

- Free scores by Constant Lambert at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- 'The Jazz Age', lecture and concert by Chamber Domaine given on 6 November 2007 at Gresham College, including the Suite in Three Movements for Piano by Lambert (available for audio and video download).

- Constant Lambert (1905–1951), Composer, conductor and critic: Sitter in 24 portraits (National Portrait Gallery)

- Constant Lambert at IMDb

- Constant Lambert: Dionysian Modernist, Dr Anthony Smith PhD, Australian National University, PhD thesis 2017, accessed 2022-07-15

- 1905 births

- 1951 deaths

- 20th-century British classical composers

- 20th-century British conductors (music)

- 20th-century British male musicians

- 20th-century English musicians

- Alumni of the Royal College of Music

- British ballet composers

- British male classical pianists

- British male conductors (music)

- British male film score composers

- British people of American descent

- Burials at Brompton Cemetery

- Composers for piano

- Deaths from diabetes in the United Kingdom

- Deaths from pneumonia in England

- English classical composers

- English conductors (music)

- English male classical composers

- English people of Australian descent

- Jazz-influenced classical composers

- Lambert family

- People educated at Christ's Hospital

- Pupils of Ralph Vaughan Williams