Mellah of Fez

The Mellah of Fez (Arabic: ملاح) is the historic Jewish quarter (Mellah) of Fez, Morocco. It is located in Fes el-Jdid, the part of Fez which contains the Royal Palace (Dar al-Makhzen), and is believed to date from the mid-15th century. While the district is no longer home to any significant Jewish population, it still contains a number of monuments and landmarks from the Jewish community's historical heritage in the city.

History

[edit]Background: the Jewish community before the Mellah (9th to 14th centuries)

[edit]

Fez had long hosted the largest and one of the oldest Jewish communities in Morocco, present since the city's foundation by the Idrisids (in the late 8th or early 9th century).[1][2] They lived in many parts of the city alongside the Muslim population, as evidenced by the fact that Jewish houses were purchased and demolished for the Almoravid expansion of the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque (located at the center of the city), and by the claims of Maimonides' residence in what later became the Dar al-Magana (in the western part of the city).[3][4] Nonetheless, since the time of Idris II (early 9th century) the Jewish community was more or less concentrated in the neighbourhood known as Foundouk el-Yihoudi ("hotel/warehouse of the Jew") near Bab Guissa in the northeast of the city.[4][1][2] The city's original Jewish cemetery was also located near here, just outside the gate of Bab Guissa.[2]

As elsewhere in the Muslim world, the Jewish population lived under the protected but subordinate status of dhimmi, required to pay a jizya tax but able to move relatively freely and cultivate relations in other countries.[5][6] Fez, along with Cordoba, was one of the centers of a Jewish intellectual and cultural renaissance taking place in the 10th and 11th centuries in Morocco and al-Andalus (Spain and Portugal under Muslim rule).[6][5] A number of major figures such as Dunash Ben Labrat (poet, circa 920-990), Judah ben David Hayyuj (or Abu Zakariyya Yahya; grammarian, circa 945-1012), and the great Talmudist Isaac al-Fasi (1013-1103) were all born or spent time in Fez.[5] Maimonides also lived in Fez from 1159 to 1165 after fleeing al-Andalus.[7][6] This age of prosperity came to an end, however, with the advent of Almohad rule in Morocco and Al-Andalus. The Almohads, who officially followed the radical reformist ideology of Ibn Tumart, abolished the jizya and the status of dhimmi, enforcing repressive measures against non-Muslims and other reforms. Jews under their rule were widely forced to convert or be exiled, with some converting but continuing to practice their Jewish faith in secret.[6][5]

The decline of the Almohads and the rise of the Marinid dynasty's rule over Morocco in the 13th century brought a more tolerant climate in which the Jewish community was able to recover and grow again.[6][5] Following the pogroms of 1391 under Spanish rule, in places like Seville and Catalonia, a large number of Spanish Jews (also referred to as Megorashim or rūmiyīn) fled to North Africa and settled in cities like Fez.[5]

Creation of the Mellah (15th century)

[edit]

In 1276 the Marinids had founded Fes el-Jdid, a new fortified administrative city to house their royal palace and army barracks, located to the west of Fes el-Bali ("Old Fez").[1][8] Later in the Marinid period the Jewish inhabitants of Fes el-Bali were all moved to a new district in the southern part of Fes el-Jdid. This district, possibly created after the 1276 foundation,[1]: 66 was located between the inner and outer southern walls of the city and was initially inhabited by Muslim garrisons, notably by the Sultan's mercenary contingents of Syrian archers.[1][9] These regiments were disbanded around 1325 under Sultan Abu Sa'id.[8] The district was first known as Hims, but also by the name Mellah (Arabic: ملاح, lit. 'salt' or 'saline area')[10] due to either a saline water source in the area or to the former presence of a salt warehouse.[4][2][8] This second name was later retained as the name of the Jewish quarter.[1] This was the first "mellah" in Morocco; a name and phenomenon that came to be replicated in many other cities such as Marrakech.[11][12][2] (A notable exception being the nearby town of Sefrou.[2])

Both the exact reasons and the exact date for the creation of the Jewish Mellah of Fez are not firmly established.[13][4] Historical accounts confirm that in the mid-14th century the Jews of Fez were still living in Fes el-Bali but that by the end of the 16th century they were well-established in the Mellah of Fes el-Jdid.[1] Moroccan scholar Hicham Rguig, for example, states that the transfer is not precisely dated and argues that it likely happened in stages across the Marinid period (late 13th to 15th centuries), particularly following episodes of violence or repression against Jews in the old city.[4] One of the earliest such instances of violence was a revolt in 1276 against the new Marinid dynasty, right before Sultan Abu Yusuf Ya'qub decided to found Fes el-Jdid. The revolt shook the whole city but also resulted in much violence against the Jewish inhabitants, which may have incited Abu Yusuf Ya'qub to intervene in some way to protect the community.[4] Susan Gilson Miller, a scholar of Moroccan and Jewish history, has also noted that the urban fabric of the Mellah appears to have developed progressively and it's thus possible that a small Jewish population settled here right after the foundation of Fes el-Jdid and that other Jews fleeing the old city joined them later.[6] Many authors, citing historical Jewish chronicles, attribute the main transfer more specifically to the "rediscovery" of Idris II's body in his old mosque at the center of the city in 1437.[6][10][14][15][13] The area around the mosque, located in the middle of the city's main commercial districts, was turned into a horm (sanctuary) where non-Muslims were not allowed to enter, resulting in the expulsion of the Jewish inhabitants and merchants there.[4] At least several authors claim that the expulsion was further enforced to all of Fes el-Bali because it was given the status of a "holy" city as a result of the discovery.[6][15][13][16] Other scholars also date the move generally to the mid-15th century, without arguing for a specific date.[2][5] In any case, the transfer (whether progressive or sudden) occurred with some violence and hardship.[6] Many Jewish households chose to convert (at least officially) rather than leave their homes and their businesses in the heart of the old city, resulting in a growing group referred to as al-Bildiyyin (Muslim families of Jewish origin, often retaining Jewish surnames).[5][13]

Broader political motivations for moving the Jewish community to Fes el-Jdid, closer to the royal palace, may have included the rulers' desire to take more direct advantage (or control) of their artisan skills and of their commercial relations with Jewish communities in Europe and other countries (which could be used for diplomatic purposes).[2][4] The Mellah's Jewish cemetery was established at its southwestern edge (around what is now Place des Alaouites near the Royal Palace gates) on land which was donated to the Jewish community by a Marinid princess named Lalla Mina in the 15th century.[8][2]

The 15th century was also a time of political instability, with the Wattasid viziers taking over effective control from the Marinid dynasty and competing with other local factions in Fez.[6] In 1465, the Mellah was attacked by the Muslim population of Fes el-Bali during a revolt led by the shurafa (noble sharifian families) against the Marinid sultan Abd al-Haqq II and his Jewish vizier Harun ibn Battash.[5] The attack resulted in thousands of Jewish inhabitants being killed, with many others having to openly renounce their faith. The community took at least a decade to recover from this, growing again under the rule of the Wattasid sultan Muhammad al-Shaykh (1472-1505).[5]

Later history of the Mellah (late 15th to 19th centuries)

[edit]

In subsequent centuries the fortunes of the Mellah and the Jewish community of Fez varied according to circumstances, including general circumstances that affected all inhabitants of Fez such as famine or war.[6] The Mellah's location inside the more heavily fortified Fes el-Jdid and close to the Royal Palace made it relatively secure, but the Jewish community nonetheless suffered disasters at various periods.

Major changes to the community occurred when in 1492 the Spanish crown expelled all Jews from Spain, with Portugal doing the same in 1497. The following waves of Spanish Jews migrating to Fez and North Africa increased the Jewish population and also altered its social, ethnic, and linguistic makeup.[5] According to the Flemish scholar Nicolas Cleynaerts who stayed in the mellah from 1540 to 1541, the Jewish quarter had an estimated population of 4000 at this time.[6][17] The influx of migrants also revitalized Jewish cultural activity in the following years, while splitting the community along ethnic lines for many generations.[5] The Megorashim of Spanish origin retained their heritage and their Spanish language while the indigenous Moroccan Toshavim, who spoke Arabic and were of Arab and Berber heritage, followed their own traditions. Members of the two communities worshiped in separate synagogues and were even buried separately. It was only in the 18th century that the two communities eventually blended together, with Arabic eventually becoming the main language of the entire community while the Spanish (Sephardic) minhag became dominant in religious practice.[6]

The community continued to thrive or suffer depending on conditions. In the 17th century a significant influx of Jews from the Tadla region and from the Sous Valley arrived under the reigns of the Alaouite sultans Moulay Rashid and Moulay Isma'il, respectively.[1] In 1641, Muhammad al-Haj of the Dilā' Sufi order occupied Fes. This became a particularly difficult time for Fessi Jews. A Jewish chronicle of the time recounts that in 1646 he ordered synagogues to close, and these were subsequently desecrated, damaged, or destroyed.[18]: 88–89 Serious hardship also took place in 1790 to 1792 during a period of general turmoil and decline under Sultan Moulay Yazid.[1] During these two years the sultan forced the entire Jewish community to move next to the outlying Kasbah Cherarda on the other side of Fes el-Jdid.[6] The Mellah was occupied by tribal troops allied to him, its synagogue was replaced by a mosque, and the Jewish cemetery and its contents were moved to a cemetery near Bab Guissa. Moreover, Moulay Yazid permanently reduced the size of the district by demolishing the old city walls around it and rebuilding them along a much smaller perimeter.[4][1] It was only after the sultan's death that the chief Muslim qadi (judge) of Fez ordered the Mellah to be restored to the Jewish community, along with the demolition of the mosque built by Yazid's troops.[6]

The fortunes of the Jewish community improved considerably in the 19th century when the expansion of contact and trade with Europe allowed the Jewish merchant class to place themselves at the center of international trade networks in Morocco.[6] This also led to a greater social openness and a shift in tastes and attitudes, especially among richer Jews, who built luxurious residences in the upper Mellah.[6]

By the end of the 19th century the district had some 15 synagogues.[6] In 1894, the Sultan ordered the old Jewish Cemetery, located at the base of the Royal Palace's outer wall, to be moved in order to accommodate an expansion of the palace.[4] As a result, the cemetery and its contents were moved to a new location at the southeastern corner of the Mellah, where it is still found today. However, other authors attribute this displacement of the cemetery to the French administration's works in the area in 1912, noting that tombs were still present in the old cemetery up until 1912.[1][8] The current cemetery to the southeast had probably existed from the early 19th century but was still largely empty in its eastern parts before the 20th century.[1][6]

20th century and present day

[edit]

In 1912 French colonial rule was instituted over Morocco following the Treaty of Fes. One immediate consequence was the 1912 riots in Fez, a popular uprising which included deadly attacks targeting Europeans as well as native Jewish inhabitants in the Mellah (perceived as being too close to the new administration), followed by an even deadlier repression against the general population.[20] Fez and its Royal Palace ceased to be the center of power in Morocco as the capital was moved to Rabat. A number of social and physical changes took place at this period and across the 20th century. Starting under Lyautey, the creation of the French Ville Nouvelle ("New City") to the west also had a wider impact on the entire city's development.[21]

In the area around the Bab al-Amer gate, on the southwestern edge of the Mellah, the French administration judged the old gate too narrow and inconvenient for traffic and demolished a nearby aqueduct and some of the surrounding wall in order to improve access.[8] In the process they created a large open square on the site of the earlier Jewish cemetery which became known as Place du Commerce, now also adjoined by the larger Place des Alaouites.[8] In 1924, the French went further and demolished a series of modest shops and stables on the northern edge of the Jewish Mellah in order to build a wide road for vehicles (Rue Boukhessissat or Bou Khsisat; later also Rue des Mérinides) between the Mellah and the southern wall of the Royal Palace.[8][22] The former shops were replaced with more ostentatious boutiques built in the architectural style of the Jewish houses of the Mellah, with many open balconies and outward ornamentation.[8]

While the population of Fez and Fes el-Jdid increased over this period, in the second half of the 20th century the Mellah became steadily depopulated of its Jewish inhabitants who either moved to the Ville Nouvelle, to Casablanca, or emigrated to countries like France, Canada, and Israel.[23] In the late 1940s, estimates of the Jewish population include 15,150 in the Mellah and 22,000 in all of Fez.[8][23] Major waves of emigration after this depleted the Jewish population. The district was progressively taken over instead by other Muslim residents, who make up its population today. In 1997 there were reportedly only 150 Jews in all of Fez and no functioning synagogues remained in the Mellah.[23]

Layout and organisation of the Mellah

[edit]

The Mellah's layout took shape progressively over the centuries and has been modified multiple times, especially after periods of destruction by fire or political repression (such as Moulay Yazid's reduction of the Mellah's size in 1790-92).[6] Due to constant reconstructions, few of its buildings are very old compared to the monuments of Fes el-Bali, though some synagogues, for example, are believed to have been established at their locations for centuries (even if they were rebuilt recently).[6]

The main street of the Mellah (Derb al-Souq)

[edit]

The Mellah was historically entered from the northeast. It occupies a district in the south of Fes el-Jdid, outside the main inner Marinid wall whose main gate here was Bab Semmarine.[8] Directly south of Bab Semmarine was the Sidi Bou Nafa' neighbourhood, which flanked the east side of the Mellah. Sidi Bou Nafa' was a traditionally Muslim neighbourhood whose outline can still be made out today. It is adjoined by a Saadian-era bastion of the same name to the east.[1] Directly across from Bab Semmarine a street descends south and west through this neighbourhood until it reaches Bab el-Mellah, a gate set inside a borj (a tower or bastion) which marked the official entrance to the Mellah proper.

Bab el-Mellah originally had a bent entrance but now has a straight passage.[1] Despite this modification, the area near it is believed to be the oldest part of the Mellah.[6] Just south of the gate, inside the boundary of the Mellah, is the Slat al-Fassiyin Synagogue, believed to be the oldest synagogue of the district.[6] West of Bab el-Mellah, the main street from Bab Semmarine continues in a roughly straight line towards the southwest. This street constituted the main street and souq (market) of the Mellah, and was thus also called Derb al-Souq ("Street of the Market"). The street may have been much wider originally and featured a large market square, but over time it was steadily encroached upon by the construction of shops and houses.[6] The street's western end is very narrow and was once a cul-de-sac, but it was opened up after 1912 when the French created the open square called Place du Commerce behind Bab al-Amer, thus allowing pedestrians today to enter the Mellah from the west side as well.[8] The main market street also marks a rough division between the "Upper" and "Lower" Mellah.[1]

The Upper Mellah

[edit]

The Upper Mellah was centered around Derb al-Fouqi, a street which branched off Derb al-Souq from just inside Bab el-Mellah. Derb al-Fouqi, also referred to as the "High Street",[6] ran north and roughly parallel to the main street to the south. It finished in a dead-end to the west, but was still connected to the main street via several other alleys running between them.[6] This neighbourhood contained the residences of the Jewish community's bourgeoisie and upper class, as evidenced by the existence of many rich houses, the best-known example of which was the Ben Simhon House.[1] Many of these households were of Spanish or Iberian origin.[2] These luxurious houses were especially concentrated on the northern edge of the Mellah, bordering the former Bou Khsisat Gardens and the outer wall of the Mellah, because this location allowed them more exposure to fresh air and open space.[1][6] Moreover, by being able to have their balconies and windows face north they were also slightly cooler in the summer.[1]

As this neighbourhood was more strictly private and residential, it had few public amenities. One exception was the neighbourhood oven, used for baking bread, which was operated by Muslims (so that it could continue to make bread on the Sabbath).[6] Derb al-Fouqi was also home to many workshops producing the goods which the Jewish community specialized in, such as sqalli (gold thread used to decorate textiles and other objects).[6][24] Following the creation of Rue Boukhessissat (or Bou Khsisat) between the former northern boundary of the Mellah and the southern wall of the Royal Palace by the French in 1924, this new road was lined with a new row of relatively ornate Jewish houses and boutiques which are still visible today.[8][9]

The Lower Mellah

[edit]

The "Lower" Mellah was generally poorer and denser than the Upper Mellah.[1] The urban fabric to the south of the main street (Derb al-Souq) was probably also the oldest.[6] Here the streets are especially convoluted due to constant encroachment by expanding houses over time. Many workshops were also found here, especially near the market street.[6] Many lanes led to impasses which were in turn shut off by gates at their entrance, creating private mini-neighbourhoods.[6] Some of the more public streets were only just wide enough to allow for rituals and events such as the parading of a young man on his bar mitzvah.[6] It is also in this neighbourhood that the Mellah's oldest synagogues are found, such as the Ibn Danan Synagogue and the Slat al-Fassiyin Synagogue. On the northern edge of the cemetery, in the southern part of the district, was once located the community's abattoir.[1][6] Other public amenities and services in the area included a mikveh, an oven, and schools.[6]

The Jewish Cemetery

[edit]

The southwest corner of the Mellah is occupied by a large Jewish Cemetery, which existed since the early 19th century but was only filled to its current extent in the 20th century.[6][1] This has been the main cemetery of the Mellah since the old cemetery, situated to the northwest at the base of the Royal Palace's walls, was forced to move in 1894 by order of the sultan,[4] or possibly by order of the French after 1912.[8] The cemetery was managed by the local Hebra Qadisha, who also served as the community's firefighters.[2] Today, a small former synagogue at the northeastern end of the cemetery is used as a small museum.[2]

En-Nowawel Quarter

[edit]To the east of the cemetery and south of the Sidi Bou Nafa' neighbourhood is a relatively recent neighbourhood called En-Nowawel or An-Nawawil, which likely dates from the end of the 19th century.[6] Its name refers to the straw huts which initially existed here as crude shelters for its inhabitants.[6][1] The latter were probably recent migrants to the Mellah from rural towns.[1] Over time, regular housing was built in their place. Between the cemetery and En-Nowawel there was once an open space used for games.[1][6] The neighbourhood also had its own oven as well as a hammam (bathhouse).[6]

Architecture of the Mellah

[edit]

Houses

[edit]

The houses of the Mellah today are notable for their marked difference from the traditional houses in the rest of the city. Whereas old houses in Fes el-Bali and the traditionally Muslim neighbourhoods of Fes el-Jdid have very few exterior features and generally closed-off from the outside, the Jewish houses in the Mellah often have open balconies facing the street and a greater number of windows.[9] Some of these balconies are even relatively ornate and have sculpted motifs, such as those on the more modern Boukhessissat street.[9] However, this characteristic is relatively recent in the architectural history of the district and older houses follow the same format as their Muslim counterparts, with an emphasis on privacy and a lack of exterior features.[6]: 314 Like other traditional historic Moroccan houses, the houses of the Mellah were centered around an interior courtyard surrounded by a gallery which spanned the multiple floors of the building. In the case of more bourgeois or wealthy households, the interior of the house could also be richly decorated with sculpted wood and stucco.[6]

Synagogues

[edit]

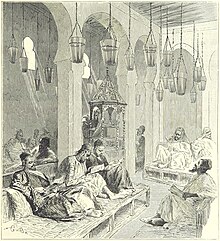

Most of the synagogues in the Mellah were merely pre-existing rooms within private residences which were converted by the owners into places of worship and sustained by member donations. As a result, almost everyone lived within a few steps of a synagogue, but very few synagogues were supported through public funding.[6] A few of them, however, were larger and were decorated with zellij mosaic tiles, carved stucco, and painted wooden ceilings, typically using much of the same decorative repertoires as Islamic architecture elsewhere in the city.[6][9]

Among the best-known synagogues of the Mellah are the Ibn Danan Synagogue, believed to date from the end of 17th century, and the Slat al-Fassiyin Synagogue, reputed to be the oldest synagogue of the Mellah and possibly dating from the Marinid period (13th-15th centuries).[6] Both may have been rebuilt various times, and their age should be interpreted as the date of their establishment at this location.[6] For a few centuries the Sephardic (Spanish) Jews, known as Megorashim, and the Moroccan (Arab or Berber) Jews, known as Toshavim, worshipped in separate synagogues, until the Sephardic tradition (minhag) eventually prevailed in most aspects of religious practice. The Slat al-Fassiyin Synagogue was one of the few where non-Sephardic rituals continued up until the 20th century.[6][1]

The names of the synagogues that existed in the Mellah of Fez in modern times are given below, grouped roughly by neighbourhood:[6]

Upper Mellah:

- Mansano Synagogue

- Ibn Attar Synagogue

- Synagogue of Rabbi Yehuda ben Attar

- Synagogue of Rabbi Haim Cohen

- Synagogue of Haham Abensur

- Synagogue of Saba

- Gozlan Synagogue

Lower Mellah:

- Shlomo Ibn Danan Synagogue (or Ibn Danan Synagogue)

- Slat al-Fassiyin Synagogue (or al-Fassiyin Synagogue)

- Bar Yochai Synagogue

- Obayd Synagogue

- Dbaba Synagogue

- Synagogue of Rabbi Raphael Abensur

En-Nowawel quarter:

- Synagogue of Aharon Cohen

- Synagogue of Saadian Danan

- Synagogue of Hachuel

- Synagogue of Rabbi El Baz

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat : étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- ^ Terrasse, Henri (1968). La Mosquée al-Qaraouiyin à Fès; avec une étude de Gaston Deverdun sur les inscriptions historiques de la mosquée. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rguig, Hicham (2014). "Quand Fès inventait le Mellah". In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. pp. 452–454. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chetrit, Joseph (2014). "Juifs du Maroc et Juifs d'Espagne: deux destins imbriqués". In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. pp. 309–311. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio; Bertagnin, Mauro (2001). "Inscribing Minority Space in the Islamic City: The Jewish Quarter of Fez (1438-1912)". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (3): 310–327. doi:10.2307/991758. JSTOR 991758.

- ^ "Moses Maimonides | Jewish philosopher, scholar, and physician". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bressolette, Henri; Delaroziere, Jean (1983). "Fès-Jdid de sa fondation en 1276 au milieu du XXe siècle". Hespéris-Tamuda: 245–318.

- ^ a b c d e Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- ^ a b Zafrani, H. "Mallāḥ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- ^ Deverdun, Gaston (1959). Marrakech: Des origines à 1912. Rabat: Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines.

- ^ Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- ^ a b c d García-Arenal, Mercedes (1987). "Les Bildiyyīn de Fès, un groupe de néo-musulmans d'origine juive". Studia Islamica. 66 (66): 113–143. doi:10.2307/1595913. JSTOR 1595913.

- ^ Chetrit, Joseph (2014). "Juifs du Maroc et Juifs d'Espagne: deux destins imbriqués". In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. pp. 309–311. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b Ben-Layashi, Samir; Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce (2018). "Myth, History, and Realpolitik: Morocco and its Jewish Community". In Abramson, Glenda (ed.). Sites of Jewish Memory: Jews in and From Islamic Lands. Routledge. ISBN 9781317751601.

- ^ Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. p. 70. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- ^ Gerber, Jane S. (1980). Jewish Society in Fez 1450-1700: Studies in Communal and Economic Life. BRILL. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-90-04-05820-0. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco : a history from pre-Islamic to postcolonial times. London. ISBN 978-1-83860-361-8. OCLC 1139892409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Fez Riots (1912)". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. doi:10.1163/1878-9781_ejiw_sim_0007730. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ Gershovich, Moshe (2000). "Pre-Colonial Morocco: Demise of the Old Mazhkan". French Military Rule in Morocco: colonialism and its consequences. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4949-X.

- ^ Jelidi, Charlotte (2012). Fès, la fabrication d'une ville nouvelle (1912-1956). ENS Éditions.

- ^ "Rue des Mérinides | Fez, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ a b c "Fez, Morocco Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- ^ Srougo, Shai (2018). "The social history of Fez Jews in the gold-thread craft between the Middle Ages and the French colonialist period (sixteenth to twentieth centuries)". Middle Eastern Studies. 54 (6): 901–916. doi:10.1080/00263206.2018.1479694. S2CID 150294174.