Nubia

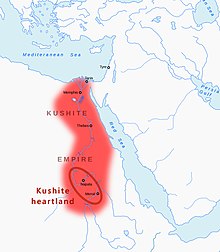

Nubia (/ˈnjuːbiə/, Nobiin: Nobīn,[2] Arabic: النُوبَة, romanized: an-Nūba) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the area between the first cataract of the Nile (south of Aswan in southern Egypt) or more strictly, Al Dabbah.[3][4][5][6] It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

From the 3rd century BC to 3rd century AD, northern Nubia was invaded and annexed to Egypt, ruled by the Greeks and Romans. This territory was known in the Greco-Roman world as Dodekaschoinos.

Kush's collapse in the fourth century AD was preceded by an invasion from the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum and the rise of three Christian kingdoms: Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia. Makuria and Alodia lasted for roughly a millennium. Their eventual decline started not only the partition of Nubia, which was split into the northern half conquered by the Ottomans and the southern half by the Sennar sultanate, in the sixteenth century, but also a rapid Islamization and partial Arabization of the Nubian people. Nubia was reunited with the Khedivate of Egypt in the nineteenth century. Today, the region of Nubia is split between Egypt and Sudan.

The primarily archaeological science dealing with ancient Nubia is called Nubiology.

| Part of a series on |

| History of Nubia |

|---|

|

|

|

Linguistics

[edit]| Nubia in hieroglyphs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ta-seti T3-stj Curved land[7] | |||||||||

Setiu Stjw Curved land of the Nubians[8] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

Nehset / Nehsyu / Nehsi Nḥst / Nḥsyw / Nḥsj Nubia / Nubians | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Historically, the people of Nubia spoke at least two varieties of Nubian languages, a subfamily that includes Nobiin (the descendant of Old Nubian), Dongolawi, Midob and several related varieties in the northern part of the Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan. The Birgid language was spoken north of Nyala in Darfur, but became extinct as late as 1970. However, the linguistic identity of the ancient Kerma culture of southern and central Nubia (also known as Upper Nubia), is uncertain; some research suggests that it belonged to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages,[9][10] while more recent studies indicate that the Kerma culture belonged to the Eastern Sudanic branch of Nilo-Saharan languages instead, and that other peoples of northern or Lower Nubia north of Kerma (such as the C-Group culture and the Blemmyes) spoke Cushitic languages before the spread of Eastern Sudanic languages from southern or Upper Nubia.[11][12][13][14]

Geography

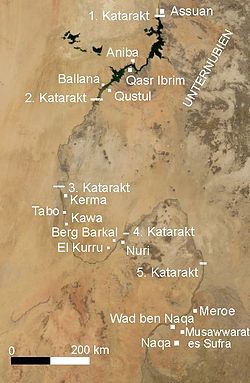

[edit]Nubia was divided into three major regions: Upper, Middle, and Lower Nubia, in reference to their locations along the Nile. "Lower" referred to regions downstream (further north) and "upper" to regions upstream (further south). Lower Nubia lay between the First and the Second Cataracts within the current borders of Egypt, Middle Nubia lay between the Second and the Third Cataracts, and Upper Nubia lay south of the Third Cataract.[15]

History

[edit]Prehistory (before 6000–3500 BC)

[edit]Archaeological evidence attests to long histories of fishing-hunting-gathering, and later herding, throughout the Nile Valley.[16]

Affad 23 is an archaeological site located in the Affad region of southern Dongola Reach in northern Sudan,[17] which hosts "the well-preserved remains of prehistoric camps (relics of the oldest open-air hut in the world) and diverse hunting and gathering loci some 50,000 years old".[18][19][20]

In southern Nubia (near modern Khartoum) from the ninth to the sixth millennia cal BC, Khartoum Mesolithic fisher-hunter-gatherers produced sophisticated pottery.[21]

By 5000 BC, the people who inhabited what is now called Nubia participated in the Neolithic Revolution. The Sahara became drier and people began to domesticate sheep, goats, and cattle.[22] Saharan rock reliefs depict scenes that have been thought to suggest the presence of a cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Eastern Africa and the Nile Valley even to this day.[23] Nubian rock art depicts hunters using bows and arrows in the neolithic period, which is a precursor to Nubian archer culture in later times.

Megaliths discovered at Nabta Playa are early examples of what seems to be one of the world's first astronomical devices, predating Stonehenge by almost 2,000 years.[24] This complexity as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[25]

American anthropologist, Joseph Vogel wrote that:

"The period when sub-Saharan Africa was most influential in Egypt was a time when neither Egypt, as we understand it culturally, nor the Sahara, as we understand it geographically, existed. Populations and cultures now found south of the desert roamed far to the north. The culture of Upper Egypt, which became dynastic Egyptian civilization, could fairly be called a Sudanese transplant."[26]

British Africanist Basil Davidson outlined that "The ancient Egyptians belonged, that is, not to any specific Egyptian region or Near Eastern heritage but to that wide community of peoples who lived between the Red Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, shared a common "Saharan-Sudanese culture", and drew their reinforcements from the same great source, even though, as time went by, they also absorbed a number of wanderers from the Near East".[27]

Biological anthropologists Shomarka Keita and A.J. Boyce have stated that the "Studies of crania from southern predynastic Egypt, from the formative period (4000-3100 B.C.), show them usually to be more similar to the crania of ancient Nubians, Kushites, Saharans, or modern groups from the Horn of Africa than to those of dynastic northern Egyptians or ancient or modern southern Europeans."[28]

Archaeological evidence has attested that population settlements occurred in Nubia as early as the Late Pleistocene era and from the 5th millennium BC onwards, whereas there is "no or scanty evidence" of human presence in the Egyptian Nile Valley during these periods, which may be due to problems in site preservation.[29] Several scholars have argued that the African origins of the Egyptian civilization derived from pastoral communities which emerged in both the Egyptian and Sudanese regions of the Nile Valley in the fifth millennium BCE.[30][31]

Dietrich Wildung (2018) examined Eastern Saharan pottery styles and Sudanese stone sculptures and suggested these artefacts were transmitted across the Nile Valley and influenced the pre-dynastic Egyptian culture in the Neolithic period.[32]

Pre-Kerma; A-Group (3500-3000 BC)

[edit]

Upper Nubia

[edit]The poorly known "pre-Kerma" culture existed in Upper (Southern) Nubia on a stretch of fertile farmland just south of the Third Cataract.

Lower Nubia

[edit]

Nubia has one of the oldest civilizations in the world. This history is often intertwined with Egypt to the north.[33]: 16 Around 3500 BC, the second "Nubian" culture, termed the Early A-Group culture, arose in Lower Nubia.[34] They were sedentary agriculturalists,[22]: 6 traded with the Egyptians and exported gold.[35] This trade is supported archaeologically by large amounts of Egyptian commodities deposited in the A-Group graves. The imports consisted of gold objects, copper tools, faience amulets and beads, seals, slate palettes, stone vessels, and a variety of pots.[36] During this time, the Nubians began creating distinctive black topped, red pottery. The A-Group population have been described as ethnically “very similar” to the pre-dynastic Egyptians in physical characteristics.[37]

Around 3100 BC, the A-group transitioned from the Early to Classical phases. "Arguably royal burials are known only at Qustul and possibly Sayala."[35]: 8 During this period, the wealth of A-group kings rivaled Egyptian kings. Royal A-group graves contained gold and richly decorated pottery.[33]: 19 Some scholars believe Nubian A-Group rulers and early Egyptian pharaohs used related royal symbols; similarities in A-Group Nubia and Upper Egypt rock art support this position. Scholars from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute excavated at Qustul (near Abu Simbel in Sudan), in 1960–64, and found artifacts which incorporated images associated with Egyptian pharaohs.

Archeologist Bruce Williams studied the artifacts and concluded that "Egypt and Nubia A-Group culture shared the same official culture", "participated in the most complex dynastic developments", and "Nubia and Egypt were both part of the great East African substratum".[38] Williams also wrote that Qustul "could well have been the seat of Egypt's founding dynasty".[39][40] David O'Connor wrote that the Qustul incense burner provides evidence that the A-group Nubian culture in Qustul marked the "pivotal change" from predynastic to dynastic "Egyptian monumental art".[41] However, "most scholars do not agree with this hypothesis",[42] as more recent finds in Egypt indicate that this iconography originated in Egypt instead of Nubia, and that the Qustul rulers adopted or emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.[43][44][45][46]

According to David Wengrow, the A-Group polity of the late 4th millenninum BCE is poorly understood since most of the archaeological remains are submerged underneath Lake Nasser.[47] Frank Yurco also remarked that depictions of pharonic iconography such as the royal crowns, Horus falcons and victory scenes were concentrated in the Upper Egyptian Naqada culture and A-Group Nubia. He further elaborated that "Egyptian writing arose in Naqadan Upper Egypt and A-Group Nubia, and not in the Delta cultures, where the direct Western Asian contact was made, further vitiates the Mesopotamian-influence argument".[48]

The archaeological cemeteries at Qustul are no longer available for excavations since the flooding of Lake Nasser.[49] The earliest representations of pharaonic iconography have been excavated from Nag el-Hamdulab in Aswan, the extreme southern region of Egypt which borders the Sudan, with an estimated dating range between 3200 and 3100 BC.[50]

Egypt in Nubia

[edit]Writing developed in Egypt around 3300 BC. In their writings, Egyptians referred to Nubia as "Ta-Seti", or "The Land of the Bow," as the Nubians were known to be expert archers.[51] More recent and broader studies have determined that the distinct pottery styles, differing burial practices, different grave goods, and site distribution all indicate that the Naqada people and the Nubian A-Group people were from different cultures.

Kathryn Bard states that "Naqada cultural burials contain very few Nubian craft goods, which suggests that while Egyptian goods were exported to Nubia and were buried in A-Group graves, A-Group goods were of little interest further north."[52] According to anthropologist Jane Hill, there is no evidence that the pharaohs of the First Dynasty of Egypt buried at Abydos were of Nubian origin.[53] However, several biological anthropological studies have shown the Badarian and Naqada people to be closely related to the Nubian and other, tropical African populations.[54][55][56][57][58][59] Also, the proto-dynastic kings emerged from the Naqada region.[60][61]

Early Kerma (3000–2400 BC)

[edit]A uniform culture of nomadic herders, called the Gash group, existed from 3000 to 1500 BC to the east and west of Nubia.[22]: 8

In Lower Nubia, the A-group moved from the Classical to Terminal phase. At this time, kings at Qustul likely ruled all of Lower Nubia and demonstrated the political centralization of Nubian society.[22]: 21 The A-Group culture came to an end sometime between 3100 and 2900 BC, when it was apparently destroyed by the First Dynasty rulers of Egypt.[62] There are no records of settlement in Lower Nubia for the next 600 years. Old Kingdom Egyptian dynasties (4th to 6th) controlled uninhabited Lower Nubia and raided Upper Nubia.

Early Kerma; C-Group (2400–1550 BC)

[edit]Upper Nubia

[edit]

The pre-Kerma developed into the Middle phase Kerma group. Some A-group people (transitioning to C-group) settled the area and co-existed with the pre-Kerma group.[22]: 25 Like other Nubian groups, the two groups made an abundance of red pottery with black tops, though each group made different shapes.[22]: 29 Traces of the C-group in Upper Nubia vanish by 2000 BC and Kerma culture began to dominate Upper Nubia.[22]: 25 The power of an independent Upper Nubia increased around 1700 BC and Upper Nubia dominated Lower Nubia.[22]: 25 An Egyptian official, Harkhuf, mentions that Irtjet, Setjet, and Wawat all combined under a single ruler. By 1650 BC, Egyptian texts started to refer to only two kingdoms in Nubia: Kush and Shaat.[22]: 32, 38 Kush was centered at Kerma and Shaat was centered on Sai island.[22]: 38 Bonnet posits that Kush actually ruled all of Upper Nubia, since "royal" graves were much larger in Kush than Shaat and Egyptian texts other than the Execration lists only refer to Kush (and not Shaat).[22]: 38–39

Lower Nubia

[edit]C-group Nubians resettled Lower Nubia by 2400 BC.[22]: 25 As trade between Egypt and Nubia increased, so did wealth and stability. Nubia was divided into a series of small kingdoms. There is debate over whether the C-group people,[63] who flourished from 2500 BC to 1500 BC, were another internal evolution or invaders. O'Connor states "a transition from A group into a later culture, the C-group, can be traced" and the C-group culture was typical of Lower Nubia from 2400 to 1650 BC.[22]: 25 Although they lived in close proximity to each other, Nubians did not acculturate much to Egyptian culture. Notable exceptions include C-group Nubians during the 15th Dynasty, isolated Nubian communities in Egypt, and some bowmen communities.[22]: 56 C-Group pottery is characterized by all-over incised geometric lines with white infill and impressed imitations of basketry. Lower Nubia was controlled by Egypt from 2000 to 1700 BC and Upper Nubia from 1700 to 1525 BC.

From 2200 to 1700 BC, the Pan Grave culture appeared in Lower Nubia.[33]: 20 Some of the people were likely the Medjay (mḏꜣ,[64]) arriving from the desert east of the Nile river. One feature of Pan Grave culture was shallow grave burial. The Pan Grave and C-Group definitely interacted: Pan Grave pottery is characterized by more limited incised lines than the C-Group's and generally have interspersed undecorated spaces within the geometric schemes.[65]

Egypt in Nubia

[edit]

In 2300 BC, Nubia was first mentioned in Old Kingdom Egyptian accounts of trade missions. The Egyptians referred to Lower Nubia as Wawat, Irtjet, and Setju, while they referred to Upper Nubia as Yam. Some authors believe that Irtjet and Setju could also have been in Upper Nubia.[22]: 32 They referred to Nubians dwelling near the river as Nehasyu.[22]: 26

From Aswan, the southern limit of Egyptian control at the time, Egyptians imported gold, incense, ebony, copper, ivory, and exotic animals from tropical Africa through Nubia. Relations between the Egyptians and Nubians showed peaceful cultural interchange, cooperation, and mixed marriages. Nubian bowmen that settled at Gebelein during the First Intermediate Period married Egyptian women, were buried in Egyptian style, and eventually could not be distinguished from Egyptians.[22]: 56

Older scholarship noted that some Egyptian pharaohs may have had Nubian ancestry.[66][67] Richard Loban expressed the view that Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty "was quite possibly of Nubian origin" and cited historical evidence which mentioned that Amenemhet I, founder of the 12th Dynasty, "had a Ta Seti or Nubian mother".[68][69][70] Dietrich Wildung has argued that Nubian features were common in Egyptian iconography since the pre-dynastic era and that several pharaohs such as Khufu and Mentuhotep II were represented with these Nubian features.[71]

Frank Yurco wrote that "Egyptian rulers of Nubian ancestry had become Egyptians culturally; as pharaohs, they exhibited typical Egyptian attitudes and adopted typical Egyptian policies". Yurco noted that some Middle Kingdom rulers, particularly some pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty had strong Nubian features, due to the origin of the dynasty in the Aswan region of southern Egypt. He also identified the pharaoh Sequenre Tao of the Seventeenth Dynasty, as having Nubian features.[72] Many scholars in recent years have argued that the mother of Amenemhat I, founder of the Twelfth Dynasty was of Nubian origin.[73][74][69][75][76][77][78]

After a period of withdrawal, the Middle Kingdom of Egypt conquered Lower Nubia from 2000 to 1700 BC.[22]: 8, 25 By 1900 BC, King Sesostris I began building a series of towns below the Second Cataract with heavy fortresses that had enclosures and drawbridges.[33]: 19 Sesotris III relentlessly expanded his kingdom into Nubia (from 1866 to 1863 BC) and erected massive river forts including Buhen, Semna, Shalfak and Toshka at Uronarti to gain more control over the trade routes in Lower Nubia. They also provided direct access to trade with Upper Nubia, which was independent and increasingly powerful during this time. These Egyptian garrisons seemed to peacefully coexist with the local Nubian people, though they did not interact much with them.[79]

Medjay was the name given by ancient Egypt to nomadic desert dwellers from east of the Nile river. The term was used variously to describe a location, the Medjay people, or their role/job in the kingdom. They became part of the Egyptian military as scouts and minor workers before being incorporated into the Egyptian army.[citation needed] In the army, the Medjay served as garrison troops in Egyptian fortifications in Nubia and patrolled the deserts as a kind of gendarmerie,[80] or elite paramilitary police force,[81] to prevent their fellow Medjay tribespeople from further attacking Egyptian assets in the region.[81]

The Medjay were often used to protect valuable areas, especially royal and religious complexes. Although they are most notable for their protection of the royal palaces and tombs in Thebes and the surrounding areas, the Medjay were deployed throughout Upper and Lower Egypt; they were even used during Kamose's campaign against the Hyksos and became instrumental in turning the Egyptian state into a military power.[82][83] After the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, the Medjay district was no longer mentioned in written records.[84]

Kerma; Egyptian Empire (1550–1100 BC)

[edit]Upper Nubia

[edit]

From the Middle Kerma phase, the first Nubian kingdom to unify much of the region arose. The Classic Kerma culture, named for its royal capital at Kerma, was one of the earliest urban centers in the Nile region and oldest city in Africa outside of Egypt.[85][22]: 50–51 The Kerma group spoke either languages of the Cushitic branch[9][10] or, according to more recent research, Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch.[11][12][13][14]

By 1650 BC (Classic Kerma phase), the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor for monumental town walls and large mud brick structures, such as the Eastern and Western Deffufas (50 by 25 by 18 meters). They also had rich tombs with possessions for the afterlife and large human sacrifices. George Andrew Reisner excavated sites at the royal city of Kerma and found distinctive Nubian architecture, such as large pebble covered tombs (90 meters in diameter), a large circular dwelling, and a palace-like structure.[22]: 41 Classic Kerma rulers employed "a good many Egyptians", according to the Egyptian Execration texts.[22]: 57

Kerma culture was militaristic, as attested by many archers' burials and bronze daggers/swords found in their graves.[22]: 31 Other signs of Nubia's military prowess are the frequent use of Nubians in Egypt's military and Egypt's need to construct numerous fortresses to defend their southern border from the Nubians.[22]: 31 Despite assimilation, the Nubian elite remained rebellious during Egyptian occupation. There were numerous rebellions and "military conflict occurred almost under every reign until the 20th dynasty".[86]: 102–103 At one point, Kerma came very close to conquering Egypt: Egypt suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Kingdom of Kush.[87][88]

According to Davies, head of the joint British Museum and Egyptian archaeological team, the attack was so devastating that, if the Kerma forces had chosen to stay and occupy Egypt, they might have permanently eliminated the Egyptians and brought the nation to extinction. During Egypt's Second Intermediate period, the Kushites reached the height of their Bronze Age power and completely controlled southern trade with Egypt.[22]: 41 They maintained diplomatic ties with the Thebans and Hyksos until the New Kingdom pharaohs brought all of Nubia under Egyptian rule from 1500 to 1070 BC.[22]: 41 After 1070 BC, there were continued hostilities with Egypt, which led Nubians to concentrate in Upper Nubia.[22]: 58 Within 200 years, a fully formed Kushite state, based at Napata, began to exert its influence on Upper (Southern) Egypt.[22]: 58–59

Lower Nubia

[edit]When the Middle Kingdom Egyptians pulled out of the Napata region around 1700 BC, they left a lasting legacy that was merged with indigenous C-group customs. Egyptians remaining at the garrison towns started to merge with the C-group Nubians in Lower Nubia. The C-group quickly adopted Egyptian customs and culture, as attested by their graves, and lived together with the remaining Egyptians in garrison towns.[22]: 41 After Upper Nubia annexed Lower Nubia around 1700 BC, the Kingdom of Kush began to control the area. At this point, C-group Nubians and Egyptians began to proclaim their allegiance to the Kushite King in their inscriptions.[22]: 41 Egypt conquered Lower and Upper Nubia from 1500 to 1070 BC. However, the Kingdom of Kush survived longer than Egypt.

Egypt in Nubia

[edit]

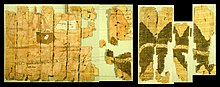

After the Theban 17th Dynasty New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1532–1070 BC) expelled the Canaanite Hyksos from Egypt, they turned their imperial ambitions to Nubia. By the end of Thutmose I's reign (1520 BC), all of Lower Nubia had been annexed. After a long campaign, Egypt also conquered the Kingdom of Kerma in Upper Nubia and held both areas until 1070 BC.[86]: 101–102 [22]: 25 The Egyptian empire expanded into the Fourth Cataract, and a new administrative center was built at Napata, which became a gold and incense production area.[89][90] Egypt became a prime source of gold in the Middle East. The primitive working conditions for the slaves are recorded by Diodorus Siculus.[91] One of the oldest maps known is of a gold mine in Nubia: the Turin Papyrus Map dating to about 1160 BC; it is also one of the earliest characterized road maps in existence.[92]

Nubians were an integral part of New Kingdom Egyptian society. Some scholars state that Nubians were included in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt's royal family.[93] Ahmose-Nefertari, "arguably the most venerated woman in Egyptian history",[94] was thought by some scholars such as Flinders Petrie to be of Nubian origin because she is most often depicted with black skin.[66][95]: 17 [96] The mummy of Ahmose-Nefertari's father, Seqenenre Tao, has been described as presenting "tightly curled, woolly hair", with "a slight build and strongly Nubian features".[97] Some modern scholars also believe that in some depictions, her skin color is indicative of her role as a goddess of resurrection, since black is both the color of the fertile land of Egypt and that of the underworld.[98][99]: 90 [100][94][101]: 125 However, there is no known depiction of her painted during her lifetime (she is represented with the same light skin as other represented individuals in tomb TT15, before her deification); the earliest black skin depiction appears in tomb TT161, c. 150 years after her death.: 11–12, 23, 74–5 [101]: 125 Egyptologist Barbara Lesko wrote in 1996 that Ahmose-Nefertari was "sometimes portrayed by later generations as having been black, although her coffin portrait gives her the typical light yellow skin of women."[102] In 2009, Egyptologist Elena Vassilika, noting that in a wooden statuette of the queen (now at the Museo Egizio) the face is painted black but the arms and feet are light in color, argued that the reason for the black coloring in that case was religious and not genetic.[103]: 78–9

In 1098–1088 BC, Thebes was "the scene of a civil war-like conflict between the High Priest of Amun of Thebes Amenhotep and the Viceroy of Kush Panehesy (= the Nubian)". It was chaotic and many tombs were plundered. Instead of sending soldiers to restore order, Ramesses XI put Panehesy in control of that area's military and appointed him Director of Granaries. Panehesy stationed his troops in Thebes to protect the city from thieves, but it resembled a military occupation of Thebes to the High Priest, which later led to the Civil war in Thebes.[86]: 104–105 By 1082 BC, Ramesses XI finally sent help to the High Priest. Panehesy continued his revolt and the city of Thebes suffered from "war, famine, and plunderings".[86]: 106 Panehesy initially succeeded and the High Priest fled Thebes. Panehesy pursued the High Priest as far as Middle Egypt before Egyptian forces pushed Panehesy and his troops out of Egypt and into Lower Nubia.[86]: 106 Ramesses sent new leadership to Thebes: Herihor was named the new High Priest of Thebes (and effectively King of Southern Egypt) and Paiankh was named the new Viceroy of Kush. Paiankh recaptured former Egyptian holdings in Lower Nubia as far as the second Nile cataract, but could not defeat Panehesy in Lower Nubia, who ruled the area until his death.[86]: 106 Herihor's descendants became rulers of Egypt's 21st and 22nd Dynasties.

Napatan Empire (750–542 BC)

[edit]

There are competing theories on the origins of the Kushite kings of the 25th Dynasty:[104] some scholars believe they were Nubian officials that learned "state level organization" by administering Egyptian-held Nubia from 1500 to 1070 BC,[22]: 59 such as the rebel Viceroy of Kush, Panehesy, who ruled Upper Nubia and some of Lower Nubia after Egyptian forces withdrew.[86]: 110 Other scholars believe they are descended from families of the Egyptianized Nubian elite supported by Egyptian priests or settlers.[105][106][107][104] Children of elite Nubian families were sent to be educated in Egypt then returned to Kush to be appointed in bureaucratic positions to ensure their loyalty. During the Egyptian occupation of Nubia, there were temple towns with Egyptian cults, but "production and redistribution" was based mostly on indigenous social structures.[86]: 111

The El Kurru chiefdom likely played a major role in the development of the Kingdom of Kush due to its access to gold producing areas, control of caravan routes,[86]: 112 more arable land, and participation in international trade.[86]: 121 "There can be no doubt that el-Kurru was the burial place of the ancestors of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty."[86]: 112 The early el-Kurru burials resemble Nubian Kerma/C-group traditions (contracted body, circular stone structures, burial on a bed).[86]: 121 However, by 880–815 BC, Nubian burials at el-Kurru became more Egyptian in style with "mastabas, or pyramid on mastabas, chapels, and rectangular enclosures".[86]: 117, 121–122 Alara, the first el-Kurru prince, and his successor, Kashta, were buried at el-Kurru.[86]: 123

Later documents mention Alara as the 25th Dynasty's founder and "central to a myth of the origins of the kingdom".[86]: 124–126 Alara's sister was the priestess of Amun, which created a system of royal secession and an "ideology of royal power in which Kushite concepts and practice were united with contemporary Egyptian concepts of kingship".[86]: 144 Later, Kashta's daughter, the Kushite princess Amenirdis, was installed as God's Wife of Amun Elect and later Divine Adoratrice (effectively governor of Upper Egypt), which signaled the Kushite conquest of Egyptian territories.[86]: 148

The Napatan Empire ushered in the age of Egyptian archaism, or a return to a historical past, which was embodied by a concentrated effort at religious renewal and restoration of Egypt's holy places.[86]: 169 Piye expanded the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal[35] by adding "an immense colonnaded forecourt".[86]: 163–164 Shabaka restored the great Egyptian monuments and temples, "unlike his Libyan predecessors".[86]: 167–169 Taharqa enriched Thebes on a monumental scale."[86] At Karnak, the Sacred Lake structures, the kiosk in the first court, and the colonnades at the temple entrance are all built by Taharqa and Mentuemhet. In addition to architecture, the Kingdom of Kush was deeply influenced by Egyptian culture.[108][109][110] By 780 BC, Amun was the main god of Kush and "intense contacts with Thebes" were maintained.[86]: 144 Kush used the methods of Egyptian art and writing.[111] The Nubian elite adopted many Egyptian customs and gave their children Egyptian names. Although some Nubian customs and beliefs (e.g. burial practices) continued to be practiced,[86]: 111 Egyptianization dominated in ideas, practices, and iconography.[112] The cultural Egyptianization of Nubia was at its highest levels at the times of both Kashta and Piye.[113]

Nubia in Egypt

[edit]

Kashta peacefully became King of Upper and Lower Egypt with his daughter Amendiris as Divine Adoratrice of Amun in Thebes.[86]: 144–146 Rulers of the 23rd Dynasty withdrew from Thebes to Heracleopolis, which avoided conflict with the new Kushite rulers of Thebes. Under Kashta's reign, the Kushite elite and professional classes became significantly Egyptianized.

The city-state of Napata was the spiritual capital of Kush and it was from there that Piye (spelled Piankhi or Piankhy in older works) invaded and took control of Egypt.[116] Piye personally led the attack on Egypt and recorded his victory in a lengthy hieroglyphic filled stele called the "Stele of Victory".[86]: 166 Piye's success in achieving the double kingship after generations of Kushite planning resulted from "Kushite ambition, political skill, and the Theban decision to reunify Egypt in this particular way", and not Egypt's utter exhaustion, "as frequently suggested in Egyptological studies."[35] Due to archaism, Piye mostly used the royal titulary of Tuthmosis III, but changed the Horus name from "Strong bull appearing (crowned) in Thebes" to "Strong bull appearing in Napata" to announce that the Kushites had reversed history and conquered their former Thebaid Egyptian conquerors.[86]: 154 He also revived one of the greatest features of the Old and Middle Kingdoms: pyramid construction. As an energetic builder, he constructed the oldest known pyramid at the royal burial site of El-Kurru.

According to the revised chronology, Shebitku "brought the entire Nile Valley as far as the Delta under the empire of Kush and is 'reputed' to have had Bocchoris, dynast of Sais, burnt to death".[117][86]: 166–167 Shabaka "transferred the capital to Memphis".[86]: 166 Shebitku's successor, Taharqa, was crowned in Memphis in 690 BC[86][33] and ruled Upper and Lower Egypt as Pharaoh from Tanis in the Delta.[118][117] Excavations at el-Kurru and studies of horse skeletons indicate the finest horses used in Kushite and Assyrian warfare were bred in and exported from Nubia. Horses and chariots were key to the Kushite war machine.[86]: 157–158

Taharqa's reign was a prosperous time in the empire with a particularly large Nile river flood and abundant crops and wine.[119][86] Taharqa's inscriptions indicate that he gave large amounts of gold to the temple of Amun at Kawa.[120] His army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions.[86] László Török mentions the military success was due to Taharqa's efforts to strengthen the army through daily training in long-distance running and Assyria's preoccupation with Babylon and Elam.[86] Taharqa also built military settlements at the Semna and Buhen forts and the fortified site of Qasr Ibrim.[86]

Imperial ambitions of the Mesopotamian-based Assyrian Empire made war with the 25th Dynasty inevitable. Taharqa conspired with Levantine kingdoms against Assyria:[121] in 701 BC, Taharqa and his army aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[122] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[123] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender, Herodotus' mice theory) as to why the Assyrians failed to take Jerusalem and withdrew to Assyria.[124] Sennacherib's annals record Judah was forced into tribute after the siege and Sennacherib became the ruler of the region[125] However, this is contradicted by Khor's frequent utilization of an Egyptian system of weights for trade and the twenty-year cessation in Assyria's pattern of repeatedly invading Khor (as Assyrians had before 701 and after Sennacherib's death).[126][127] In 681 BC, Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons in Babylon.

In 679 BC, Sennacherib's successor, King Esarhaddon, campaigned in Khor, destroyed Sidon, and forced Tyre into tribute in 677–676 BC. Esarhaddon invaded Egypt proper in 674 BC, but according to Babylonian records, Taharqa and his army outright defeated the Assyrians.[128] In 672 BC, Taharqa brought reserve troops from Kush, as mentioned in rock inscriptions.[86] Taharqa's Egypt still had influence in Khor during this period as Tyre's King Ba'lu "put his trust upon his friend Taharqa". Further evidence was Ashkelon's alliance with Egypt and Esarhaddon's inscription asking "if the Kushite-Egyptian forces 'plan and strive to wage war in any way' and if the Egyptian forces will defeat Esarhaddon at Ashkelon".[129] However, Taharqa was defeated in Egypt in 671 BC when Esarhaddon conquered Northern Egypt, captured Memphis, and imposed tribute before withdrawing.[118] Pharaoh Taharqa escaped to the south, but Esarhaddon captured the Pharaoh's family, including "Prince Nes-Anhuret and the royal wives",[86] and sent them to Assyria. In 669 BC, Taharqa reoccupied Memphis and the Delta, and recommenced intrigues with the king of Tyre.[118]

Esarhaddon led his army to Egypt again and, after his death in 668 BC, command passed to Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians defeated Taharqa again and advanced as far south as Thebes, but direct Assyrian control was not established.[118] The rebellion was stopped and Ashurbanipal appointed Necho I, who had been king of the city Sais, as his vassal ruler in Egypt. Necho's son, Psamtik I, was educated at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh during Esarhaddon's reign.[citation needed] As late as 665 BC, the vassal rulers of Sais, Mendes, and Pelusium were still making overtures[a] to Taharqa in Kush.[86] The vassals' plot was uncovered by Ashurbanipal and all rebels but Necho of Sais were executed.[86]

Taharqa's successor, Tantamani, sailed north from Napata with a large army to Thebes, where he was "ritually installed as the king of Egypt".[86]: 185 From Thebes, Tantamani began his reconquest and regained control of Egypt as far north as Memphis.[86]: 185 [118] Tantamani's dream stele states that he restored order from the chaos, where royal temples and cults were not being maintained.[86]: 185 After conquering Sais and killing Assyria's vassal, Necho I, in Memphis, "some local dynasts formally surrendered, while others withdrew to their fortresses".[86]: 185

The Kushites had influence over their northern neighbors for nearly 100 years until they were repelled by the invading Assyrians. The Assyrians installed the native 26th Dynasty of Egypt under Psamtik I and they permanently forced the Kushites out of Egypt around 590 BC.[130]: 121–122 The heirs of the Kushite empire established their new capital at Napata, which was also sacked by the Egyptians in 592 BC. The Kushite kingdom survived for another 900 years after being pushed south to Meroë. The Egyptianized culture of Nubia grew increasingly Africanized after the fall of the 25th Dynasty until Queen Amanishakhete acceded in 45 BC.[citation needed] She temporarily arrested the loss of Egyptian culture, but then it continued unchecked.[113]

Meroitic (542 BC–400 AD)

[edit]

Due to pressure from Assyrians and Egyptians, Meroë (800 BC – c. 350 AD) became the southern capital of the Kingdom of Kush.[86] According to partially deciphered Meroitic texts, the name of the city was Medewi or Bedewi. Meroë was in southern Nubia by the east bank of the Nile, about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, and about 200 km northeast of Khartoum. Meroë is mentioned in first-century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: "farther inland, in the country towards the west, there lies a city called Meroe". In fifth-century BC, Greek historian Herodotus described it as "a great city...said to be the mother city of the other Ethiopians."[131][132] Together, Musawwarat es-Sufra, Naqa, and Meroë formed the Island of Meroe.

The town's importance gradually increased from the beginning of the Meroitic Period, especially from the reign of Arakamani (c. 280 BC) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë from Napata (Jebel Barkal). Excavations revealed evidence of important, high ranking Kushite burials, from the Napatan Period (c. 800 – c. 280 BC) in the vicinity of the settlement called the Western cemetery. They buried their kings in small pyramids with steeply sloped sides that were based on New Kingdom Viceroy designs.[105] At its peak, the rulers of Meroë controlled the Nile Valley over a north–south straight-line distance of more than 1,000 km (620 mi).[133]

People of the Meroitic period preserved many ancient Egyptian customs but were unique in many respects. The Meroitic language was spoken in Meroë and Sudan during the Meroitic period (attested from 300 BC) before becoming extinct around 400 AD. They developed their own form of writing by using Egyptian hieroglyphs before switching to a cursive alphabetic script with 23 signs.[134] It was split into two types: Meroitic Cursive, which was written with a stylus and used for general record-keeping; and Meroitic Hieroglyphic, which was carved in stone or used for royal or religious documents. It is not well understood due to the scarcity of bilingual texts.[clarification needed] The earliest inscription in Meroitic writing dates from between 180 and 170 BC. These hieroglyphics were found engraved on the temple of Queen Shanakdakhete. Meroitic Cursive is written horizontally, and is read from right to left like all Semitic orthographies.[135] The Meroitic people worshiped the Egyptian gods as well as their own, such as Apedemak and the lion-son of Sekhmet (or Bast).

Meroë was the base of a flourishing kingdom whose wealth was centered around a strong iron industry and international trade with India and China.[136] Metalworking is believed to have happened in Meroë, possibly through bloomeries and blast furnaces.[137] The centralized control of production within the Meroitic empire and distribution of certain crafts and manufactures may have been politically important. Other important sites were Musawwarat es-Sufra and Naqa. Musawwarat es-Sufra, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was constructed in sandstone. Its main features were the Great Enclosure, the Lion Temple of Apedemak (14×9×5 meters), and the Great Reservoir. The Great Enclosure is the main structure of the site. Much of the large labyrinth-like building complex, which covers approximately 45,000 m2, was erected in third-century BC.[138]

The scheme of the site is, so far, without parallel in Nubia and ancient Egypt. According to Hintze, "the complicated ground plan of this extensive complex of buildings is without parallel in the entire Nile valley".[139] The maze of courtyards includes three (possible) temples, passages, low walls that prevent any contact with the outside world, about 20 columns, ramps and two reservoirs.[140][141] There is some debate about the purpose of the buildings, with earlier suggestions including a college, a hospital, and an elephant-training camp.[142] The Lion Temple was constructed by Arnekhamani and bears inscriptions in Egyptian hieroglyphs, representations of elephants and lions on the rear inside wall, and reliefs of Apedemak depicted as a three-headed god on the outside walls.[143] The Great Reservoir is a hafir to retain as much as possible of the rainfall of the short, wet season. It is 250 m in diameter and 6.3 m deep.[144]

Kandake, often Latinised as Candace, was the Meroitic term for the sister of the king of Kush who, due to matrilineal succession, would bear the next heir, making her a queen mother. According to scholar Basil Davidson, at least four Kushite queens — Amanirenas, Amanishakheto, Nawidemak and Amanitore — probably spent part of their lives in Musawwarat es-Sufra.[145] Pliny writes that the "Queen of the Ethiopians" bore the title Candace, and indicates that the Ethiopians had conquered ancient Syria and the Mediterranean.[146] In 25 BC the Kush kandake Amanirenas, as reported by Strabo, attacked the city of Syene (known as Aswan today) within the territory of the Roman Empire; Emperor Augustus destroyed the city of Napata in retaliation.[147][148] In the New Testament biblical account, a treasury official of "Candace, queen of the Ethiopians", returning from a trip to Jerusalem, met with Philip the Evangelist and was baptized.[149][150]

Achaemenid period

[edit]

The Achaemenids occupied the Kushan kingdom, possibly from the time of Cambyses (c. 530 BC), and more probably from the time of Darius I (550–486 BC), who mentions the conquest of Kush (Kušiya) in his inscriptions.[151][152]

Herodotus mentioned an invasion of Kush by the Achaemenid ruler Cambyses II, however, he mentions that "his expedition failed miserably in the desert".[118]: 65–66 Derek Welsby states "scholars have doubted that this Persian expedition ever took place, but... archaeological evidence suggests that the fortress of Dorginarti near the second cataract served as Persia's southern boundary."[118]: 65–66

Ptolemaic period

[edit]The Greek Ptolemaic Kingdom under Ptolemy II Philadelphus invaded Nubia in 275 BC and annexed the northern twelve miles of this territory, subsequently known as the Dodekaschoinos ('twelve-mile land').[153] Throughout the 160s and 150s BC, Ptolemy VI has also reasserted Ptolemaic control over the northern part of Nubia.[154][155]

There is no record of conflict between the Kushites and Ptolemies. However, there was a serious revolt at the end of Ptolemy IV's reign and the Kushites likely tried to interfere in Ptolemaic affairs.[118]: 67 It is suggested that this led to Ptolemy V defacing the name of Arqamani on inscriptions at Philae.[118]: 67 "Arqamani constructed a small entrance hall to the temple built by Ptolemy IV at Pselchis and constructed a temple at Philae to which Ptolemy contributed an entrance hall."[118]: 66 There is evidence of Ptolemaic occupation as far south as the Second Cataract, but recent finds at Qasr Ibrim, such as "the total absence of Ptolemaic pottery", have cast doubts on the effectiveness of the occupation.[118]: 67 Dynastic struggles led to the Ptolemies abandoning the area, so "the Kushites reasserted their control...with Qasr Ibrim occupied" (by the Kushites) and other locations perhaps garrisoned.[118]: 67

Roman period

[edit]According to Welsby, after the Romans assumed control of Egypt, they negotiated with the Kushites at Philae and drew the southern border of Roman Egypt at Aswan.[118]: 67 Theodore Mommsen and Welsby state the Kingdom of Kush became a client Kingdom, which was similar to the situation under Ptolemaic rule of Egypt. Kushite ambition and excessive Roman taxation are two theories for a revolt supported by Kushite armies.[118]: 67–68 The ancient historians, Strabo and Pliny, give accounts of the conflict with Roman Egypt.

Strabo describes a war with the Romans in first-century BC. He stated that the Kushites "sacked Aswan with an army of 30,000 men and destroyed imperial statues...at Philae."[118]: 68 A "fine over-life-size bronze head of the emperor Augustus" was found buried in Meroe in front of a temple.[118]: 68 After the initial victories of Kandake (or "Candace") Amanirenas against Roman Egypt, the Kushites were defeated and Napata was sacked.[156] Napata's fall was not a crippling blow to the Kushites and did not frighten Candace enough to prevent her from again engaging in combat with the Roman military. In 22 BC, a large Kushite force moved northward with the intention of attacking Qasr Ibrim.[157]

Alerted to the advance, Petronius again marched south and managed to reach Qasr Ibrim and bolster its defences before the invading Kushites arrived. Welsby states after a Kushite attack on Primis (Qasr Ibrim),[118]: 69–70 the Kushites sent ambassadors to negotiate a peace settlement with Petronius, which succeeded on favourable terms.[156] Trade between the two nations increased and the Roman Egyptian border being extended to "Hiera Sykaminos (Maharraqa)."[157]: 149 [118]: 70 This arrangement "guaranteed peace for most of the next 300 years" and there is "no definite evidence of further clashes."[118]: 70

During this time, different parts of the region divided into smaller groups with individual leaders (or generals), each commanding small armies of mercenaries. They fought for control of what is now Nubia and its surrounding territories, leaving the entire region weak and vulnerable to attack. Meroë would eventually be defeated by the new rising Kingdom of Aksum to their south ruled by King Ezana. A stele of Ge'ez of an unnamed ruler of Aksum thought to be Ezana was found at the site of Meroë. From his description, in Greek, he was "King of the Aksumites and the Omerites" (i.e. of Aksum and Himyar). It is likely this king ruled sometime around 330 AD. While some authorities interpret these inscriptions as proof that the Axumites destroyed the kingdom of Meroe, others note that archeological evidence points to an economic and political decline in Meroe around 300.[158] Moreover, some view the stele as military aid from Aksum to Meroe to quell the revolt and rebellion. From then on, the Romans referred to the area as Nobatia.

Christian Nubia

[edit]

Around 350 AD, the area was invaded by the Kingdom of Aksum and the Meroitic kingdom collapsed. Three smaller Christian kingdoms replaced it: the northernmost was Nobatia (capital Pachoras; now modern-day Faras, Egypt) between the first and second cataract of the Nile River; in the middle was Makuria (capital Old Dongola), and southernmost was Alodia (capital Soba). King Silky of Nobatia defeated the Blemmyes and recorded his victory in a Greek language inscription carved in the wall of the temple of Talmis (modern Kalabsha) around 500 AD.

Christianity had been introduced to the region by the fourth century: Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated Marcus as bishop of Philae before his death in 373 AD. John of Ephesus records that a Miaphysite priest named Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around 545 AD. He also writes that the kingdom of Alodia was converted around 569. However, John of Biclarum wrote that the kingdom of Makuria converted to Catholicism the same year, suggesting that John of Ephesus might be mistaken. Further doubt is cast on John's[clarification needed] testimony by an entry in the chronicle of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria Eutychius of Alexandria, which states that in 719 AD the church of Nubia transferred its allegiance from the Greek to the Coptic Orthodox Church. After the official Christianization of Nubia, the Isis cult of Philae remained for the sake of the Nubians. The edict of Theodosius I (390 AD) was not enforced at Philae. Later attempts to suppress the cult of Isis led to armed clashes between the Nubians and Romans. Finally, in 453 AD, a treaty recognizing the traditional religious rights of Nubians at Philae was signed.

By the seventh century, Makuria expanded and became the dominant power in the region. It was strong enough to halt the southern expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After several failed invasions the new Muslim rulers agreed to a treaty with Dongola, called Baqt, to allow peaceful coexistence and trade, contingent on the Nubians making an annual payment consisting of slaves and other tributes to the Islamic Governor at Aswan; it guaranteed that any runaway slaves were returned to Nubia.[159] The treaty was kept for six hundred years.[159] Throughout this period, Nubia's main exports were dates and slaves, though ivory and gold were also exchanged for Egyptian ceramics, textiles, and glass.[160] Over time the influx of Arab traders introduced Islam to Nubia and it gradually supplanted Christianity. After an interruption in the annual tribute of slaves, the Egyptian Mamluk ruler invaded in 1272 and declared himself sovereign over half of Nubia.[159] While there are records of a bishop Timothy at Qasr Ibrim in 1372, his see included Faras. It is also clear that the cathedral of Dongola had been converted to a mosque in 1317.[161]

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom around 1504. A vast majority of the Nubian population is currently Muslim, and the Arabic language is their main medium of communication in addition to their indigenous Nubian language. The unique characteristic of Nubian is shown in their culture (dress, dances, traditions, and music).

Islamic Nubia

[edit]In the fourteenth century, the Dongolan government collapsed and the region was divided and dominated by Arabs. Several Arab invasions into the region and the establishment of smaller kingdoms occurred over the next few centuries. Northern Nubia was brought under Egyptian control, while the south was controlled by the Kingdom of Sennar in the sixteenth century. The entire region came under Egyptian control during Muhammad Ali's rule in the early nineteenth century, and later became a joint Anglo-Egyptian condominium.

21st-century archaeology

[edit]The paleo-demography of Nubians from the upper paleolithic to late 16th century BC were analyzed by Aleksandra Pudlo. Mesolithic period inhabitants were characterized as robust and tall, with strong alveolar prognathism. During the Neolithic, Nubians were less robust and shorter, retaining some prognathism, but having facial shape changes and a narrower nasal index. Over a period of 8,500 years, the features had shifted a considerable degree. The variety of morphological forms which occurred was considered a result of the combination of two distinct traits, with Pudlo concluding: "Nubians were hardly a homogeneous population. Neither the climate nor the specific geographic conditions in the region they inhabited were conducive of such homogeneity." The populations were possibly influenced by migration waves coming from the north, but these movements did not prevent repeated contacts of the people of Nubia with other regions further south in Africa.[162]

Findings were recorded in 2016 on Nubian remains over a period of 11,000 years: "Taken together, our results suggest a dramatic shift in cranial morphology between the Mesolithic and the A-group cultural group, with little perceptible change in cranial shape between A-group and the later farming groups. In the case of the mandible, we observe the largest morphological change between the Mesolithic and the A-group, but also see morphological differentiation between the early farmers (A and C-group) and the later farming groups (Pharaonic and Meroitic specimens)." Changes were attributed to factors such as in situ adaptation or influxes of people, as well as migration of farmers. Nonetheless, authors concluded further studies with larger samples and a combination of morphometric analyses and ancient DNA are needed.[163]

In 2003, archaeologist Charles Bonnet led a team of Swiss archaeologists to excavate near Kerma and discovered a cache of monumental black granite statues of the Pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty of Egypt, now displayed at the Kerma Museum. Among the sculptures are ones belonging to the dynasty's last two pharaohs, Taharqa and Tanoutamon, whose statues are described as "masterpieces that rank among the greatest in art history".[164] Craniometric analysis of Kerma fossils that compared them to various other early populations inhabiting the Nile Valley and Maghreb found that they were morphologically close to Predynastic Egyptians from Naqada (4000–3200 BC).[165] Dental trait analysis of Kerma fossils found affinities with various populations inhabiting the Nile Valley, Horn of Africa, and Northeast Africa, especially to other ancient populations from the central and northern Sudan. Among the sampled populations, the Kerma people were overall nearest to the Kush populations in Upper Nubia, the A-Group culture bearers of Lower Nubia, and Ethiopians.[166]

Contemporary issues

[edit]Nubia was divided between Egypt and Sudan after colonialism ended and the Republic of Egypt was established in 1953, and the Republic of Sudan seceded from Egypt in 1956.

In the early-1970s, many Egyptian and Sudanese Nubians were forcibly relocated to make room for Lake Nasser after dams were constructed at Aswan.[167] Nubian villages can be found north of Aswan on the west bank of the Nile and on Elephantine Island. Many Nubians now live in large cities like Cairo and Khartoum.[167]

Ancient DNA

[edit]In 2014, a male infant skeleton was recovered during an excavation in what is present-day Wadi Halfa from the Christian Period (500-1400 C.E.), located near the Second Cataract of the Nile in the Republic of the Sudan. The results from the Principal component analysis (PCA) had the individual placed between African and European clusters. Furthermore, the individual was assigned to L5a1a, a branch of the ancient L5 haplogroup with origins in East Africa.[168]

Another analysis in 2015 studied a Nubian individual from an archeological site in Kulubnarti. The geographic ancestry of the individual was estimated to be closer to Middle Eastern, and Central and South Asians, rather than to any African populations.[169]

Sirak et al. 2021 obtained and analyzed the whole genomes of 66 individuals from the site of Kulubnarti situated in northern Nubia between the 2nd and 3rd cataract, near the modern Egyptian border, and dated to the Christian period between 650 and 1000 CE. The samples were obtained from two cemeteries. The samples' genetic profile was found to be a mixture between West Eurasian and Sub Saharan Dinka-related ancestries, with ~60% West Eurasian related ancestry that likely came from ancient Egyptians but ultimately resembles that found in Bronze or Iron Age Levantines, and ~40% Dinka-related ancestry.

The two cemeteries showed minimal differences in their West Eurasian/Dinka ancestry proportions. These findings in addition to multiple cross cemetery relatives that the analyses have revealed indicate that people of both the R and S cemeteries were part of the same population despite the archaeological and anthropological differences between the two burials showing social stratification.

Modern Nubians, despite their superficial resemblance to the Kulubnarti Nubians on the PCA, were not found to be descended from Kulubnarti Nubians without additional later admixtures. Modern Nubians were found to have an increase in Sub-Saharan ancestry along with a change in their west Eurasian ancestry from that which was found in the ancient samples.[170]

A sample from historic Lower Nubia, in the Nubian site of Sayala during the 3rd-6th Century AD, belonged to mtDNA haplogroup J1c.[171]

In 2022, DNA was sequenced from the hair of a Kerma period individual (4000 BP), and the results revealed close genetic affinity to early pastoralists from the Rift Valley in eastern Africa during the Pastoral Neolithic.[172]

Nubian Images

[edit]-

Nubian terracotta female figurine from the Neolithic period ca. 3500–3100 BC Brooklyn Museum

-

Nubian king with bow, Buhen Fortress, 1650 BC, Univ. of Chicago Museum

-

Nubian Tribute Presented to the King, Tomb of Huy MET DT221112

-

Nubians bringing tribute for King Tut, Tomb of Huy

-

Temple of Amun, Jebel Barkal

-

Entrance to Great Enclosure, Musawwarat es-Sufra

-

Column and elephant – part of temple complex in Musawwarat es-Sufra

-

Pyramid of Amanishakheto

-

Jewelry of Kandake Amanishakheto

-

Copy of relief from Naqa depicting Amanitore (second from left), Natakamani (second from right) and two princes approaching a three-headed Apedemak.

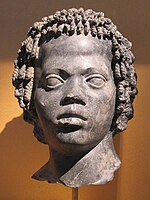

-

The "Archer King", an unknown king of Meroe, 3rd century BC. National Museum of Sudan.

-

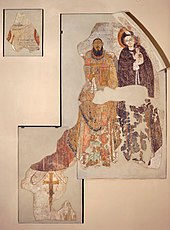

Bishop Petros, Christian Nubia

-

The Relief of Gebel Sheikh Suleiman probably shows the victory of an early Pharaoh, possibly Djer, over A-Group Nubians circa 3000 BC.

-

Now gone Christian Nubian wall painting in the Temple of Kalabsha

See also

[edit]- Doukki Gel

- Kerma culture

- List of monarchs of Kerma

- Kingdom of Kush

- List of monarchs of Kush

- Napata

- Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

- Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt

- Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt family tree

- Meroë

- Kandake, Queens of Meroe

- Military of ancient Nubia

- Nubian pyramids

- Nubiology

- Merowe Dam

- Aethiopia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache".

- ^ Reinisch, Leo (1879). Die Nuba-Sprache. Wien. p. 271.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- ^ Janice Kamrin; Adela Oppenheim. "The Land of Nubia". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ "SudanHistory.org".

- ^ Raue, Dietrich (2019-06-04). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042038-8.

- ^ a b Elmar Edel: Zu den Inschriften auf den Jahreszeitenreliefs der "Weltkammer" aus dem Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre, Teil 2. In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Nr. 5. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1964, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Christian Leitz et al.: Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, Bd. 6: H̱-s. Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1151-4, p. 697.

- ^ a b Bechaus-Gerst, Marianne; Blench, Roger (2014). Kevin MacDonald (ed.). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography – "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. p. 453. ISBN 978-1135434168. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ a b Behrens, Peter (1986). Libya Antiqua: Report and Papers of the Symposium Organized by Unesco in Paris, 16 to 18 January 1984 – "Language and migrations of the early Saharan cattle herders: the formation of the Berber branch". Unesco. p. 30. ISBN 9231023764. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ a b Rilly C (2010). "Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan" (PDF).

- ^ a b Rilly C (January 2016). "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millennia BCE". Faits de Langues. 47: 151–163. doi:10.1163/19589514-047-01-900000010. S2CID 134352296.

- ^ a b Rilly C (2008). "Enemy brothers. Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Polish Centre for Mediterranean Archaeology. doi:10.31338/uw.9788323533269.pp.211-226. ISBN 9788323533269.

- ^ a b Cooper J (2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubian placenames in the Third and Second Millennium BCE: a view from Egyptian Records". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23.

- ^ Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 90, 106. ISBN 9780415369886.

- ^ Garcea, Elena A.A. (2020). "The Prehistory of the Sudan". SpringerBriefs in Archaeology. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47185-9. ISBN 978-3-030-47187-3. ISSN 1861-6623. S2CID 226447119.

- ^ Osypiński, Piotr; Osypińska, Marta; Gautier, Achilles (2011). "Affad 23, a Late Middle Palaeolithic Site With Refitted Lithics and Animal Remains in the Southern Dongola Reach, Sudan". Journal of African Archaeology. 9 (2): 177–188. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10186. ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 43135549. OCLC 7787802958. S2CID 161078189.

- ^ Osypiński, Piotr (2020). "Unearthing Pan-African crossroad? Significance of the middle Nile valley in prehistory" (PDF). National Science Centre.

- ^ Osypińska, Marta (2021). "Animals in the history of the Middle Nile" (PDF). From Faras to Soba: 60 years of Sudanese–Polish cooperation in saving the heritage of Sudan. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology/University of Warsaw. p. 460. ISBN 9788395336256. OCLC 1374884636.

- ^ Osypińska, Marta; Osypiński, Piotr (2021). "Exploring the oldest huts and the first cattle keepers in Africa" (PDF). From Faras to Soba: 60 years of Sudanese–Polish cooperation in saving the heritage of Sudan. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology/University of Warsaw. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9788395336256. OCLC 1374884636.

- ^ Salvatori, Sandro (2012-12-01). "Disclosing Archaeological Complexity of the Khartoum Mesolithic: New Data at the Site and Regional Level". African Archaeological Review. 29 (4): 399–472. doi:10.1007/s10437-012-9119-7. ISSN 1572-9842. S2CID 254195716.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae O'Connor, David (1993). Ancient Nubia: Egypt's Rival in Africa. University of Pennsylvania, USA: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. pp. 1–112. ISBN 0924171286.

- ^ "Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith". ucsb.edu.

- ^ PlanetQuest: The History of Astronomy – Retrieved on 2007-08-29

- ^ Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa – by Fred Wendorf (1998)

- ^ Vogel, Joseph (1997). Encyclopedia of precolonial Africa : archaeology, history, languages, cultures, and environments. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press. pp. 465–472. ISBN 0761989021.

- ^ Davidson, Basil (1991). Africa in history : themes and outlines (Rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Collier Books. p. 15. ISBN 0684826674.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka and Boyce, A.J. (December 1996). "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", In Egypt in Africa, Theodore Celenko (ed). Indiana University Press. pp. 20–33. ISBN 978-0253332691.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gatto, Maria C. "The Nubian Pastoral Culture as Link between Egypt and Africa: A View from the Archaeological Record".

- ^ Wengrow, David; Dee, Michael; Foster, Sarah; Stevenson, Alice; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk (March 2014). "Cultural convergence in the Neolithic of the Nile Valley: a prehistoric perspective on Egypt's place in Africa". Antiquity. 88 (339): 95–111. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00050249. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 49229774.

- ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (1 January 2018). "Gift of the Nile? Climate Change, the Origins of Egyptian Civilization and Its Interactions within Northeast Africa". Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile: Studies in Egyptology, Nubiology and Late Antiquity Dedicated to László Török. Budapest: 325–345.

- ^ E. Pischikova, J. P. Budka, & K. Grifn (Eds. (2018). Wildung, D "African in Egyptian Art" In Thebes in the first millennium BC : art and archaeology of the Kushite period and beyond. London. pp. 300–380. ISBN 978-1906137595.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Haynes, Joyce (1992). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 8–59. ISBN 0878463623.

- ^ Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (2002). A Dictionary of Archaeology. Wiley. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-631-23583-5.

- ^ a b c d Emberling, Geoff (2011). Kim, Julienne (ed.). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York University: The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 5–57. ISBN 9780615481029.

- ^ Hafsaas, Henriette (January 2009). "Hierarchy and heterarchy – the earliest cross-cultural trade along the Nile". Connecting South and North. Sudan Studies from Bergen in Honour of Mahmoud Salih. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- ^ Mohktar, Gamal (1981). General History of Africa volume 2: Ancient Civilizations of Africa: (Unesco General History of Africa. London: Heinemann Educational Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-0435948054.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ^ "The Nubia Salvage Project | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu.

- ^ O'Connor, David Bourke; Silverman, David P (1995). Ancient Egyptian Kingship. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004100411. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ O'Connor, David (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2003-10-23). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. OUP Oxford. p. 63. ISBN 9780191604621. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ D. Wengrow (2006-05-25). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa …. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780521835862. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Peter Mitchell (2005). African Connections: An Archaeological Perspective on Africa and the Wider World. Rowman Altamira. p. 69. ISBN 9780759102590. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ László Török (2009). Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt …. BRILL. p. 577. ISBN 978-9004171978. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313325014. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Wengrow, David (2023). "Ancient Egypt and Nubian: Kings of Flood and Kings of Rain" in Great Kingdoms of Africa, John Parker (eds). [S.l.]: THAMES & HUDSON. pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-0500252529.

- ^ Frank J.Yurco (1996). "The Origin and Development of Ancient Nile Valley Writing," in Egypt in Africa, Theodore Celenko (ed). Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Lobban, Richard A. Jr. (20 October 2020). Historical Dictionary of Medieval Christian Nubia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-5381-3341-5.

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan; Darnell, John Coleman; Gatto, Maria Carmela (December 2012). "The earliest representations of royal power in Egypt: the rock drawings of Nag el-Hamdulab (Aswan)". Antiquity. 86 (334): 1068–1083. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00048250. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 53631029.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the study of the ancient world. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, by Kathryn A. Bard, 2015, p. 110

- ^ Hill, Jane A. (2004). Cylinder Seal Glyptic in Predynastic Egypt and Neighboring Regions. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-588-9.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (September 1990). "Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 83 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830105. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 2221029.

- ^ Tracy L. Prowse, Nancy C. Lovell. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 101, Issue 2, October 1996, Pages: 237–246

- ^ Godde, Kane. "A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period (2020)". Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (November 2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or "European"AgroNostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1975–1986. pp. 500–509. ISBN 9780521222150.

- ^ The Oxford history of ancient Egypt (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2003. p. 479. ISBN 0192804588.

- ^ "Ancient Nubia: A-Group 3800–3100 BC". The Oriental Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^

- Hafsaas, Henriette (January 2006). "The C-Group people in Lower Nubia, 2500 – 1500 BC. Cattle pastoralists in a multicultural setting". The Lower Jordan River Basin programme publications and global moments of the Levant. 10. Bergen. Retrieved 2016-06-08 – via academia.edu.

- Hafsaas, Henriette (2021). "The C-Group People in Lower Nubia: Cattle Pastoralists on the Frontier between Egypt and Kush". In Geoff Emberling; Bruce Beyer Williams (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Oxford University Press. pp. 157–177. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190496272.013.10.

- ^ Erman & Grapow, Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, 2, 186.1–2

- ^ de Souza, A.M. 2019. "New Horizons: The Pan-Grave Ceramic Tradition in Context. London: Golden House"

- ^ a b Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p.155 - ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey William (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0.

- ^ Lobban, Richard A. (2003-12-09). Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6578-5.

- ^ a b Lobban, Richard A. Jr. (10 April 2021). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Nubia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538133392.

- ^ Morris, Ellen (2018-08-06). Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-3677-8.

- ^ Wildung, Dietrich. About the autonomy of the arts of ancient Sudan. In M. Honegger (Ed.), Nubian archaeology in the XXIst Century. pp. 105–112.

- ^ F. J. Yurco, "The ancient Egyptians..", Biblical Archaeology Review (Vol 15, no. 5, 1989)

- ^ General History of Africa Volume II – Ancient civilizations of Africa (ed. G Moktar). UNESCO. p. 152.

- ^ Crawford, Keith W. (1 December 2021). "Critique of the "Black Pharaohs" Theme: Racist Perspectives of Egyptian and Kushite/Nubian Interactions in Popular Media". African Archaeological Review. 38 (4): 695–712. doi:10.1007/s10437-021-09453-7. ISSN 1572-9842. S2CID 238718279.

- ^ Morris, Ellen (6 August 2018). Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4051-3677-8.

- ^ Van de Mieroop, Marc (2021). A history of ancient Egypt (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. p. 99. ISBN 978-1119620877.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fletcher, Joann (2017). The story of Egypt : the civilization that shaped the world (First Pegasus books paperback ed.). New York. pp. Chapter 12. ISBN 978-1681774565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (8 October 2018). "Ethnicity: Constructions of Self and Other in Ancient Egypt". Journal of Egyptian History. 11 (1–2): 113–146. doi:10.1163/18741665-12340045. ISSN 1874-1665. S2CID 203315839.

- ^ Hafsaas, Henriette (January 2010). "Between Kush and Egypt: The C-Group people of Lower Nubia during the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period". Between the Cataracts. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- ^ Bard, op.cit., p. 486

- ^ a b Wilkinson, op.cit., p. 147

- ^ Shaw, op.cit., p. 201

- ^ Steindorff & Seele, op.cit., p. 28

- ^ Gardiner, op.cit., p. 76*

- ^ Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette (2009). "The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System". Norwegian Archaeological Review. 42 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1080/00293650902978590. S2CID 154430884. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 132–133, 153–184. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- ^ Tomb Reveals Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret The Times (London, 2003)

- ^ "Elkab's hidden treasure". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15.

- ^ James G. Cusick (5 March 2015). Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology. SIU Press. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-8093-3409-4.

- ^ Richard Bulliet; Pamela Crossley; Daniel Headrick (1 January 2010). The Earth and Its Peoples. Cengage Learning. pp. 66–. ISBN 0-538-74438-3.

- ^ Anne Burton (1973). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. BRILL. pp. 129–. ISBN 90-04-03514-1.

- ^ James R. Akerman; Robert W. Karrow (2007). Maps: Finding Our Place in the World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-01075-5.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1881). History of Ancient Egypt, Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 209.

- ^ a b Gestoso Singer, Graciela. "Ahmose Nefertari, the Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 1–118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- ^ Martin Bernal (1987), Black Athena: Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. The Fabrication of Ancient Greece, 1785-1985, vol. I. New Jersey, Rutgers University Press

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1989). "Were the ancient Egyptians black or white?". Biblical Archaeology Review. 15: 24–29.

- ^ Gitton, Michel (1973). "Ahmose Nefertari, sa vie et son culte posthume". École Pratique des Hautes études, 5e Section, Sciences Religieuses. 85 (82): 84. doi:10.3406/ephe.1973.20828. ISSN 0183-7451.

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- ^ Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 268.

- ^ a b Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- ^ The Remarkable Women of Ancient Egypt, by Barbara S. Lesko; page 14; B.C. Scribe Publications, 1996; ISBN 978-0-930548-13-1

- ^ Vassilika, Elena (2009). I capolavori del Museo Egizio di Torino (in Italian). Florence: Fondazione Museo delle antichità egizie di Torino. ISBN 978-88-8117-950-3.

- ^ a b Fage, John; Tordoff, with William (2013-10-23). A History of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79727-2.

- ^ a b "Sudan | History, Map, Flag, Government, Religion, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Piye | king of Cush". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Middleton, John (2015-06-01). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- ^ Drury, Allen (1980). Egypt: The Eternal Smile : Reflections on a Journey. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385001939.

- ^ "Museums for Intercultural Dialogue - Statue of Iriketakana". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Cush (Kush)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "statue | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2013-07-04). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45669-6.

- ^ a b "Nubia | Definition, History, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Dive beneath the pyramids of Sudan's black pharaohs". National Geographic. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019.

- ^ "The Kushite Conquest of Egypt". SudanHistory.org. 2 July 2022.

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. Penguin Books. pp. 106–107, 133–134. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ a b Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 071410986X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 158. ISBN 071410986X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 169. ISBN 071410986X.

- ^ Coogan, Michael David; Coogan, Michael D. (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-19-513937-2.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 141–144. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 127, 129–130, 139–152. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 119. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq (Third ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-012523-X.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 155–156. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 152–153. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 158–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 159–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 75, 77–78. ISBN 9780415369886.

- ^ Herodotus (1949). Herodotus. Translated by J. Enoch Powell. Translated by Enoch Powell. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 121–122.