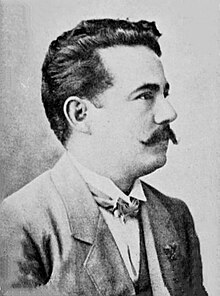

Manuel Domínguez (politician)

Manuel Domínguez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of Paraguay | |

| In office 9 January 1902 – 25 November 1902 | |

| Preceded by | Juan Cancio Flecha |

| Succeeded by | Pedro Pablo Peña |

| Vice President of Paraguay | |

| In office 25 November 1902 – 19 December 1904 | |

| President | Juan Antonio Escurra |

| Preceded by | Andrés Héctor Carvallo |

| Succeeded by | Emiliano González Navero |

| Minister of Justice, Religion and Public Education of Paraguay | |

| In office 17 January 1911 – 5 July 1911 | |

| Preceded by | Eusebio Ayala |

| Succeeded by | Federico Codas |

| Minister of Finance of Paraguay | |

| In office 1 June 1911 – 5 July 1911 | |

| Preceded by | José Antonio Ortiz |

| Succeeded by | Francisco Bareiro |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 June 1868 Pilar, Paraguay |

| Died | 29 October 1935 (aged 67) Asunción, Paraguay |

| Spouses |

|

| Parents |

|

Manuel Domínguez (5 June 1868 – 29 October 1935) was a Paraguayan politician, diplomat and writer. He was Vice President of Paraguay during colonel Juan Antonio Escurra's government (1902–1904), but fought against his forces during the civil war in 1904. He would thus be one of the few colorados to be politically relevant during the rival Liberal Party's hegemony of power which ensued after said conflict, even being Minister of Justice, Religion and Public Education during Albino Jara's troubled presidency, which immediately preceded the 1911 civil war.

Biography

[edit]Early life and career

[edit]Manuel Domínguez was born on June 5th 1868, in Pilar, a town on the shore of the Paraguay River. His father, Matias Goiburú, was an officer in the Paraguayan Army, and when Manuel was born the Siege of Humaitá, perhaps the most important battle of the Paraguayan War, raged on nearby. As a youth, he received a grant to study in the prestigious Colegio Nacional de la Capital in Asunción, Paraguay's capital.[1] As a teenage student, he started working for a newspaper, La Democracia.

Later on, he would study law while maintaining his duties as a journalist; even after he finished his studies and became a professor, he still was an active contributor to the press. He had a large career in education - he was director of the Colegio Nacional, taught constitutional law in the Universidad Nacional de Asunción's law school[2] and was said University's dean between July 1901 and January 1902. At some point in his life, he was also director for the National Archives in Asunción. Regarding his periodistic career, he would write for El Progreso in the 1890s, a pro-Juan Bautista Egusquiza paper,[3] and from 1900 onwards at La Prensa and several magazines, something which he did until his death in 1935. As a lawyer, he defended José Segundo Decoud in a trial regarding a letter Decoud purportedly would have sent to Argentinian authorities asking for Paraguay's annexation to that country in the aftermath of the Triple Alliance War;[4] the quality of Domínguez's defense is a subject of controversy.[5][6][7]

Trajectory as a politician

[edit]He was elected national deputy in the 1890s,[8][9] and vice president in late 1902, as Juan Antonio Escurra's running mate. Between January and November of 1902 he was also Minister of Foreign Affairs; his contributions to Paraguayan foreign policy and relations are some of his most significant to the country's history. Besides opening several permanent diplomatic stations in foreign countries during his term as minister, later on (up to the 1911 Civil War) he was Paraguay's main negotiator with Bolivia regarding the Chaco border issue, and also did archival work, looking for documents to support Paraguay's stance on this matter. For this role, he earned the moniker "lawyer for the nation".[1]

During his vice presidency, he abandoned president Escurra's government in 1904 in favor of a rebellion led by the rival Liberal Party.[10] In a manifesto, he attributed this to Escurra's policy errors and the deviation from the government plan written before their election by Domínguez himself. He closed said manifesto in the following manner:

Where lies the homeland? It definitely does not lie with those that make battalions with prisoners to defend a cause worthy of such soldiers. It lies where there is selflessness and intelligence. With the revolution, which doesn't bring about war in the name of any political party, is the Homeland. And with these considerations I join its ranks. Colonel Escurra's Government is morally dead.[11][a]

In 1911, during Albino Jara's government, he was Justice, Religion and Public Education Minister between January and early July, and Interior Minister between June and July. He reformed the Universidad Nacional[12] and created a system of grants for interchange studies for its students. When Jara's government fell, as the 1911 civil war started, Domínguez was ousted from the aforementioned offices.[13]

Cultural life

[edit]Domínguez was a prominent writer and orator, with works in fiction, history and law. H. G. Warren called him the "foremost literary figure of the Colorado Era".[14][b] His book "El Alma de la Raza" [The Race's Soul] contains an essay on the martial history of the Paraguayan people titled "Causas del Heroísmo Paraguayo" [Reasons for Paraguayan Heroism], which goes as far as Aleixo Garcia's invasion of the Inca Empire together with a Guaraní army in the 16th century. He spent much of his time in the capital's archives, looking for evidence both for his own scholarly pursuits and to bulk up Paraguay's claim to the Chaco.

He was a permanent member of the prestigious Instituto Paraguayo,[15] the country's then-foremost intellectual association. In it, he sustained a debate between the late 1900s and early 1910s with the Spanish anarchist Rafael Barrett over the living conditions of the Paraguayan peasantry.[16]

Later life and death

[edit]He first married Manuela González Filisbert, and then later Carmen Urbieta Peña.

He died in Asunción in 29 October 1935,[2] a few months after the victorious conclusion of the Chaco War versus Bolivia, which finally settled the border disputes that were the key point of his work as a diplomat.

Works

[edit]Among his numerous writings are:

- “Derecho constitucional” [Constitutional law]

- “El alma de la raza”; [The Race's soul]

- “Paraguay, sus grandezas y sus glorias”, [Paraguay, its greatnesses and glories]

- “El chaco Boreal”; [The Boreal Chaco]

- “El Dorado enigma de la Historia Americana”; [El Dorado, enigma in American History]

His works were collected under a compendium titled "Estudios Históricos y literarios” [Historical and literary studies].

Honors and legacy

[edit]In Luque, in Greater Asunción, there is a school named after him.[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is a translation from the original Spanish, which reads: "¿Dónde está la patria? No está seguramente con quienes forman batallones con presidiarios para defender una causa digna de tales soldados. Está allí donde hay desinterés e inteligencia. Con la revolución, que no trae la guerra en nombre de ningún partido político, está la Patria. Y en estas consideraciones me fundo al incorporarme a sus filas. El Gobierno del Coronel Escurra está moralmente muerto."

- ^ The Colorado era lasted between 1878 (Candido Bareiro's election) and 1904, when, after the Liberal Revolution, the Liberal Party took power.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Benítez 1986.

- ^ a b "Necrology". Bulletin of the Pan American Union. 70. Union of American Republics. 1936.

- ^ Warren 1985, pp. 88.

- ^ Aquino 1985, p. 197.

- ^ Aquino 1985, p. 201.

- ^ Zubizarreta 1985.

- ^ Alcalá 1999, p. 58.

- ^ "Sesiones del periodo legislativo de 1895 y 1896". babel.hathitrust.org.

- ^ "Sesiones del periodo legislativo de 1899 y 1900". babel.hathitrust.org.

- ^ Aquino 1985, p. 211-212.

- ^ Pastore 2013, p. 282.

- ^ Amaral 2006, p. 111.

- ^ "Registro Oficial correspondiente al año de 1911". babel.hathitrust.org.

- ^ Warren 1985, pp. 293.

- ^ Warren 1985, pp. 347.

- ^ Telesca, Ignacio (2012). "El debate Domínguez-Barrett: Implicancias sociales de la idea de 'nación mestiza'" (PDF). Revista Paraguaya de Sociología (in Spanish). 141.

- ^ "Colegio Dr Manuel Domínguez". colegiodmd.edu.py. Retrieved 2024-12-12.

Sources

[edit]- Alcalá, Hugo R. (1999). Historia de la literatura paraguaya. El Lector. ISBN 9789992551943.

- Amaral, Raúl (2006). El novecentismo paraguayo. Servilibro. ISBN 9789992596104.

- Aquino, Ricardo C. (1985). La Segunda Republica Paraguaya 1869-1906. Arte Nuevo. ISBN 9789996712906.

- Benítez, Luis G. (1986). Breve historia de grandes hombres. Comuneros. ISBN 9789996712906.

- Pastore, Carlos (2013). La lucha por la tierra en el Paraguay. Intercontinental. ISBN 9995334518.

- Warren, H.G. (1985). Rebirth of the Paraguayan Republic: The First Colorado Era, 1878-1904. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822976370.

- Zubizarreta, Carlos (1985). Cien vidas paraguayas. Araverá.