Love of Christ

| Part of a series on |

| Christology |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

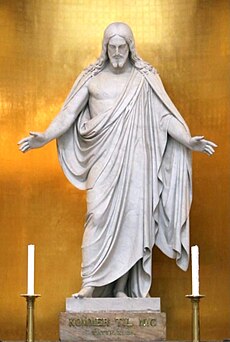

The love of Christ is a central element of Christian belief and theology.[1] It refers to the love of Jesus Christ for humanity, the love of Christians for Christ, and the love of Christians for others.[2] These aspects are distinct in Christian teachings—the love for Christ is a reflection of His love for all people.[3]

The theme of love is the key element of Johannine writings.[3] This is evidenced in one of the most widely quoted scriptures in the Bible: (John 3:16) ”For God so loved the world, that he gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth on Him should not perish, but have eternal life.” In the Gospel of John, the pericope of the Good Shepherd (John 10:1-21) symbolizes the sacrifice of Jesus based on His love for people. In that gospel, love for Christ results in the following of His commandments, the Farewell Discourse (14:23) stating: "If a man loves me, he will keep my word". In the First Epistle of John (4:19), the reflexive nature of this love is highlighted: "We love, because he first loved us", expressing the love of Christ as a mirroring of Christ's own love. Towards the end of the Last Supper, Jesus gives his disciples a new commandment: "Love one another, as I have loved you ... By this shall all men know that you are my disciples."[4][5]

The love of Christ is also a motif in the Letters of Paul.[6] The basic theme of the Epistle to the Ephesians is that of God the Father initiating the work of salvation through Christ, who willingly sacrifices Himself based on his love and obedience to the Father. Ephesians 5:25 states "Christ also loved the church, and gave Himself up for it". Ephesians 3:17-19 relates the love of Christ to the knowledge of Christ and considers loving Christ to be a necessity for knowing Him.[7]

Many prominent Christian figures have expounded on the love of Christ. Saint Augustine wrote that "the common love of truth unites people, the common love of Christ unites all Christians". Saint Benedict instructed his monks to "prefer nothing to the love of Christ".[8] Saint Thomas Aquinas stated that although both Christ and God the Father had the power to restrain those who killed Christ on Calvary, neither did, due to the perfection of the love of Christ. Aquinas also opined that, given that "perfect love" casts out fear, Christ had no fear when he was crucified, for his love was all-perfect.[9][10] Saint Teresa of Avila considered perfect love to be an imitation of the love of Christ.[11]

Love of Christ for his followers

[edit]

I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.

The love of Christ for his disciples and for humanity as a whole is a theme that repeats both in Johannine writings and in several of the Pauline Epistles.[12] John 13:1, which begins the narrative of the Last Supper, describes the love of Christ for his disciples: "having loved his own that were in the world, he loved them unto the end." This use of "to the end" in Greek (in which the gospel was written) may also be translated as "to the utmost".[12] In the First Epistle of John (4:19) the reflexive nature of this love is highlighted: "We love, because he first loved us", expressing the origin of the love as a mirroring of Christ's love.[12]

The theology of the intercession of Christ from Heaven after he left the earth, draws upon his continued love for his followers and his ongoing desire to bring them to salvation as in 1 John 2:1-2 and Romans 8:34.[13]

In many Christological models, the love of Christ for his followers is not mediated by any other means but is direct. It resembles the love of the shepherd for his sheep, and the nourishment that the Vine (cf. John 15:1-17) provides for the branches.[14] In other models, the love is partially delegated to the apostles who formed the early church, and through them, it is passed to their successors.[14]

The pericope of the Good Shepherd appears about midway through the Gospel of John (10:1-21), and in John 1-11 Jesus states that as the good shepherd he will lay down his life for his sheep.[15] This concept is then basis of Jesus' commands to Apostle Peter after his resurrection and before his Ascension to Heaven.[16] In John 21:15-17, a resurrected Jesus asks Peter three times, "Do you love me?" And as a response, Jesus commands Peter three times to "feed my lambs", "tend my sheep" and "feed my sheep", implying that love for Christ should translate to loving actions and care for his followers.[16][17]

The basic theme of the Epistle to the Ephesians is that of God the Father initiating the work of salvation through Christ, who is not merely a passive instrument in this scenario but takes an active role in the work of salvation.[18] In Ephesians 5:1-2, Paul calls upon the Ephesians to be imitators of God:[18]

- Be ye therefore imitators of God, as beloved children; and walk in love, even as Christ also loved you, and gave himself up for us, an offering and a sacrifice to God.

Paul continues this idea in Ephesians 5:25 and states that: "Christ also loved the church, and gave himself up for it".[18]

The discussion of the love expressed by Christ throughout the New Testament is part of the overall theme of the outpouring of love from a merciful God and Christ's participation in it.[16] In John 14:31, Jesus explains that his sacrificial act was performed so "that the world may know that I love the Father, and as the Father gave me commandment, even so I do."[19] This verse includes the only direct statement by Jesus in the New Testament about his love for the Father.[19] In the Book of Revelation (19:7-9), the imagery of the wedding feast of the Lamb represents the celebration of the culmination of this cycle of love and mercy of God, which begins in the first chapter of the Book of Genesis, and ends in salvation.[16][20]

Love of Christians for Christ

[edit]

Let them prefer nothing to the love of Christ

— Rule of St. Benedict, item 72.[8]

In the New Testament

[edit]The theme of love is the key element of Johannine writings: "God loves Christ, Christ loves God, God loves humanity, and Christians love God through their love for Christ". Christians are bound together through their mutual love, which is a reflection of their love for Christ.[3] The word "love" appears 57 times in the Gospel of John, more often than in the other three gospels combined.[21] Additionally, it appears 46 times in the First Epistle of John.[21]

In the Gospel of John, love for Christ results in the following of his commandments. In John 14:15, Jesus states, "If you love me, you will keep my commandments." and John 14:23 reconfirms that: "If a man love me, he will keep my word".[22]

The dual aspect to the above is Jesus' commandment to his followers to love one another.[4][5] In John 13:34-35, during the Last Supper, after the departure of Judas, and just before the start of the Farewell Discourse, Jesus gives a new commandment to his eleven remaining disciples: "Love one another; as I have loved you" and states that: "By this shall all men know that you are my disciples."[4][5]

Outside of Johannine literature, the earliest New Testament reference to the love for Christ is 1 Corinthians 16:22—"If any man loveth not the Lord, let him be anathema".[23] In 2 Corinthians 5:14-15, Paul discusses how the love of Christ is a guiding force and establishes a link between Christ's sacrifice and the activities of Christians:[24]

- For the love of Christ controls us; for we are convinced that one died for all, therefore all died; and he died for all, that they who live should no longer live unto themselves, but unto him who for their sakes died and rose again.

However, Paul assures the Corinthians that he is not trying to commend himself to them. The love of Christ controls his ministry because of his conviction in the saving power of the sacrifice of Christ.[25] This dovetails into Paul's Second Adam Christology in 1 Corinthians 15 in which the birth, death and Resurrection of Jesus liberate Christians from the transgressions of Adam.[25]

In the First Epistle to the Corinthians (13:8-13), Paul views love of Christ as the key element that makes a personal communion with God possible, based on the three activities of "faith in Christ", "hope in Christ" and "love for Christ".[26] In 1 Corinthians 13:13, he states:[26] "Abide in faith, hope and love, these three; and the greatest of these is love."

The love of Christ is an important theme in the Epistle to the Romans.[6] In Romans 8:35 Paul asks, "What can separate us from the love of Christ?"[6] And he answers:[27] "Shall tribulation, or anguish, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? ... Nay, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him that loved us."

The use of "love of Christ" in Romans 8:35 and the "love of God" in 8:39 reflects Paul's focus on joining Christ and God in the experience of the believer without asserting their equality.[28]

In the Epistle to the Ephesians (3:17-19) Paul relates the love of Christ to the knowledge of Christ, and considers the love of Christ as a necessity for knowing him:[7]

- "... to know the love of Christ which is beyond all knowledge, that you may be filled until you reach the fullness of God himself."

Paul views the knowledge of Christ obtained through the "immeasurable love of Christ" (as in Ephesians 3:17-19) as surpassing other forms of spiritual knowledge, as in 1 Corinthians 2:12 which considers "spiritual knowledge" as divine knowledge acting within the human mind.[27]

Later Christian writers

[edit]Saint Augustine referred to Ephesians 3:14 and suggested that the bowing of the knees to the Father is the best way to come to know the love of Christ.[29] Then building on the concept that "the common love of truth unites people, the common love of Christ unites all Christians," Augustine taught that faith in Christ implies community in the Church, and that the goal of Christians should be the unity of mankind.[30]

Saint Benedict emphasized the importance of the love of Christ to his monks, and in keeping with the rest of his Christology, focused on the non-earthly aspects.[31] Benedict wanted his monks to love Christ as "he had loved us", and again stated the reflexive nature of the love: "prefer nothing to Christ, for he preferred nothing to us".[8][31] The Rule of Benedict also reminds the monks of the presence of Christ in the most humble and the least powerful of men, who can nonetheless experience and manifest a deep love of Christ.[31]

Saint Thomas Aquinas viewed the perfect love of Christ for humanity as a key element of his willing sacrifice as the Lamb of God and stated that although both Christ and God the Father had the power to restrain those who killed Christ on Calvary, neither did, due to the perfection of the love of Christ.[9] Referring to 1 John and Ephesians, Aquinas stated that given that "perfect love" casts out fear, Christ had no fear, for the love of Christ was all-perfect.[10] Aquinas also emphasized the importance of avoiding distractions that would separate those in religious life from their love of Christ.[32]

Saint Teresa of Avila considered perfect love to be an imitation of the love of Christ.[11] For her, the path to perfect love included a constant awareness of the love received from God, and the acknowledgement that nothing in the human soul has a claim to the outpouring of God's unconditional love.[11]

See also

[edit]- Agape, a Greek term for love with specific significance in Christian theology

- Great Commandment

- Love of God (Christianity)

- You are Christ, an early Christian prayer attributed to Augustine of Hippo

- Sacred Heart

References

[edit]- ^ Christian theology: the spiritual tradition (2002) by John Glyndwr Harris. ISBN 1-902210-22-0. Page 193.

- ^ "John 15:9-17". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ a b c The Gospel of John: The New Daily Study Bible, Vol 2 (2001) by William Barclay. ISBN 0-664-22490-3. Page 197.

- ^ a b c The Gospel of John (1998) by Francis J. Moloney and Daniel J. Harrington. ISBN 0-8146-5806-7. Page 425.

- ^ a b c The Gospel of John (1994) by Frederick Bruce. ISBN 0-8028-0883-2. Page 294.

- ^ a b c Reading Romans: a literary and theological commentary (2008) by Luke Timothy Johnson. ISBN 1-57312-276-9. Page 87.

- ^ a b The letters to the Galatians and Ephesians (2002) by William Barclay. ISBN 0-664-22559-4. Pages 152–153.

- ^ a b c Walled about with God (2005) by Jean Prou and David Hayes. ISBN 0-85244-645-4 Page 113.

- ^ a b Aquinas on Doctrine (2004) by Thomas Weinandy, John Yocum and Daniel Keating. ISBN 0-567-08411-6. Pages 123–124.

- ^ a b Summa Theologiae: Volume 49, The Grace of Christ (2006) by Thomas Aquinas and Liam G. Walsh. ISBN 0-521-02957-0. Pages 21–23.

- ^ a b c Teresa of Avila (2004) by Rowan Williams. ISBN 0-8264-7341-5. Page 108.

- ^ a b c 1-3 John, Volume 5 (2007) by John MacArthur. ISBN 0-8024-0772-2. Page 230.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Part 13 (2003) by James Hastings and John A. Selbie. ISBN 0-7661-3688-4. Page 384.

- ^ a b Who do you say that I am? Essays on Christology (1999) by Jack Dean Kingsbury, Mark Allan Powell and David R. Bauer. ISBN 0-664-25752-6. Pages 255–256.

- ^ Commentary on John (1993) by Thomas Whitelaw. ISBN 0-8254-3979-5. Page 229.

- ^ a b c d Thematic Guide to Biblical Literature (2007) by Nancy M. Tischler. ISBN 0-313-33709-8. Pages 65–67.

- ^ To Praise, to Bless, to Preach: Spiritual Reflections on the Sunday Gospels (2000) by Peter John Cameron. ISBN 0-87973-823-5. Pages 71–72.

- ^ a b c New Testament Christology (1999) by Frank J. Matera. ISBN 0-664-25694-5. Pages 155–156.

- ^ a b Preaching the Gospel of John: proclaiming the living Word (2004) by Lamar Williamson. ISBN 0-664-22533-0. Page 192.

- ^ Dictionary of biblical imagery (1998) by Leland Ryken. ISBN 0-8308-1451-5. Page 122.

- ^ a b That You Might Believe - Study on the Gospel of John (2001) by Jonathan Gainsbrugh. ISBN Page 628.

- ^ The People's New Testament Commentary (2005) by M. Eugene Boring and Fred B. Craddock. ISBN Pages 338–340.

- ^ A Commentary on I Peter (1993) by Leonhard Goppelt, Ferdinand Hahn and John Alsup. ISBN 0-8028-0964-2.

- ^ Christology in context (1988) by Marinus de Jonge. ISBN 0-664-25010-6. Page 38.

- ^ a b New Testament Christology (1999) by Frank J. Matera. ISBN 0-664-25694-5. Page 100.

- ^ a b Christ, the sacrament of the encounter with God (1987) by Edward Schillebeeckx. ISBN 0-934134-72-3. Page 182.

- ^ a b A commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians (2001) by John Muddiman. ISBN 0-8264-5203-5. Pages 172–173.

- ^ The Epistle to the Romans (1996) by Douglas J. Moo. ISBN 0-8028-2317-3. Page 547.

- ^ The Confessions of St. Augustine (2002) by St. Augustine and Albert Cook Outler. ISBN 0-486-42466-9. Pages 272–273.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo, selected writings (1988) by Mary T. Clark and Saint Augustine of Hippo. ISBN 0-8091-2573-0. Page 43.

- ^ a b c Benedict's Rule: A Translation and Commentary (1996) by Terrence G. Kardong. ISBN 0-8146-2325-5. Pages 596–597.

- ^ Reading John With St. Thomas Aquinas (2005) by Michael Dauphinais and Matthew Levering. ISBN 0-8132-1405-X. Page 98.

- Macleod, Donald (1998). The person of Christ. Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 9780851118963.

Further reading

[edit]- Knowing the love of Christ: an introduction to the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas (2002) by Michael Dauphinais and Matthew Levering. ISBN 0-268-03302-1.