Lake Chalco

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

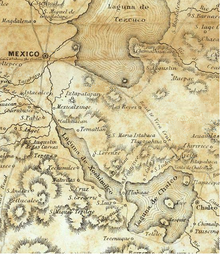

Lake Chalco was an endorheic lake formerly located in the Valley of Mexico, and was important for Mesoamerican cultural development in central Mexico. The lake was named after the ancient city of Chalco on its former eastern shore.

Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco were the original habitat of the axolotl, an amphibian that is critically endangered due to urban destruction.

Geography

[edit]Lake Chalco and the other Mexican great lakes (the brackish lakes Texcoco, Zumpango and Xaltocan and the freshwater Xochimilco) formed the ancient Basin of Mexico lake system. These lakes were home to many Mesoamerican cultures including the Toltecs and the Aztecs.

Lake Chalco itself had a fresh water hydrologic structure due in large part to the artesian springs lining its south shore. This allowed extensive chinampa beds to be cultivated through the Aztec era. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, these beds fell into disuse and were largely abandoned.

History

[edit]The shoreline of the Lake Chalco region was successful in its early history. Unlike its counterparts to the North, Lake Chalco's water was freshwater and was abundant with fish.[1] These factors lead to a period of growth in the Lake Chalco region, as around 500 BC the Chalco region was one of the most populated and dense areas in the Basin of Mexico. Around 500 BC there were around 21,810 inhabitants in Chalco, the highest at that time.[2] Its density was also the highest at 109.1 people per hectare.[2] After the emergence of Teotihuacan, the population dropped off greatly. However, there was another emergence of population in the region of Lake Chalco, and this was around 1400 AD, the population going from 75.0 people per hectare to 150 people per hectare.[2]

It is said that chinampas (in their current form) were introduced to the Chalco-Xochimilco lake bed sometime after 1400 AD.[3] It is highly probable that the growth of the Lake Chalco region was in correlation to the growth of chinampa farming. However, this growth was not due to Lake Chalco inhabitants discovering chinampa techniques, as they existed on a limited scale from 300–1350 AD.[4] The Aztec empire, led by King Itzcoatl conquered the Southern region (Lake Chalco and Xochimilco) and used this area for chinampa development.[4] The Aztec Triple Alliance needed large amounts of foodstuffs to maintain the growth of Tenochtitlan and the control of other communities through tribute; therefore, they conquered lands optimal for chinampa farming.[4] The Triple Alliance did farm other areas of the valley, however, due to arid conditions the chinampa zone was optimal for their empire.[5] During the last years of Itzcoatl’s reign, he constructed a causeway that linked Tenochtitlan to towns near Xochimilco.[6] After the Spaniards came to the Valley of Mexico, and this land was no longer supported by the Aztec infrastructure; therefore, chinampa production died down.

Starting during the Aztec era and continuing into the 20th century, efforts were made to drain Lake Chalco and her sister lakes in order to avoid periodic flooding and to provide for expansion. The only lakes that are still in existence are a diminished Lake Xochimilco and the Lake of Zumpango.

A land speculator's draining of the lake in the late 1860s led to a tenant farmer (campesino) revolt organized by Julio López Chávez that was eventually put down by the federal government.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tamayo, Jorge (1965). "Mexico's Fishing Trades: a short History". Artes de México. 68/69: 29–30.

- ^ a b c Parsons, Jeffrey (1974). "The Development of a Prehistoric Complex Society: A Regional Perspective from the Valley of Mexico". Journal of Field Archaeology. 1 (1/2): 81–108.

- ^ Siemens, Alfred (April 1983). "Wetland Agriculture in Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica". Geographical Review. 73 (2): 166–181. Bibcode:1983GeoRv..73..166S. doi:10.2307/214642. JSTOR 214642.

- ^ a b c Morehart, Christopher (2018). Holt, Emily (ed.). "The Political Ecology of Chinampa Landscapes in the Basin of Mexico". Water and Power in Past Societies. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438468754.

- ^ Coe, Michael (July 1964). "THE CHINAMPAS OF MEXICO". Scientific American. 211 (1): 90–99. Bibcode:1964SciAm.211a..90C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0764-90.

- ^ Brumfiel, Elizabeth (1983). "Aztec State Making: Ecology, Structure, and the Origin of the State". American Anthropologist. 85 (2): 261–284. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00010.

- ^ Chacón, Justin Akers (2018). Radicals in the Barrio: Magonistas, Socialists, Wobblies, and Communists in the Mexican-American Working Class. Haymarket Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-60846-776-1.