Kunbarrasaurus

| Kunbarrasaurus Temporal range: Early Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria |

| Clade: | †Parankylosauria |

| Genus: | †Kunbarrasaurus Leahey et al., 2015 |

| Species: | †K. ieversi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Kunbarrasaurus ieversi Leahey et al., 2015

| |

Kunbarrasaurus (meaning "shield lizard") is an extinct genus of small ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Australia. The genus contains a single species, K. ieversi.

Discovery

[edit]

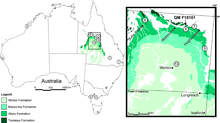

In November 1989, at Marathon Station near Richmond, Queensland, the skeleton was discovered of an ankylosaurian. In January 1990 it was secured by a team led by Ralph Molnar. In 1996, in a provisional description, Molnar concluded that it could be referred to the genus Minmi as a Minmi sp.[1] Subsequently, the specimen was further prepared by an acid bath and investigated by a CAT scan. The new information led to the conclusion that the species could be named in a separate genus of ankylosaur.[2]

In 2015, Lucy G. Leahey, Ralph E. Molnar, Kenneth Carpenter, Lawrence M. Witmer and Steven W. Salisbury named and described the type species Kunbarrasaurus ieversi. The genus name is derived from Kunbarra - the word for 'shield' in the Mayi language of the local Wunumara people. The specific name ieversi honours Mr Ian Ivers, the property manager who originally found the fossil. The description was limited to the skull.[2] Kunbarrasaurus was one of eighteen dinosaur taxa from 2015 to be described in open access or free-to-read journals.[3]

The holotype, QM F1801, was found in a layer of the Allaru Formation, marine sediments dating from the late Albian, or possibly the early Cenomanian. It consists of an almost complete skeleton with skull, containing the vertebral column up to the middle tail, the left shoulder girdle, the left arm minus the hand, the pelvis, both thighbones and most of the body armour. Both the bones and the armour are largely articulated. In the belly region remains have been found of the animal's last meal. The specimen represents the most complete dinosaur skeleton ever found in Eastern Gondwana (Australia, Antarctica, Madagascar and India) and the most complete ankylosaurian skeleton from the entirety of the Gondwanan continents.[2]

Five specimens earlier referred to a Minmi sp. were not referred to Kunbarrasaurus by the 2015 description.[citation needed]

In 2022, a specimen collected in 2005 by Benjamin P. Kear from Warra Station near Boulia, Queensland, SAMA P40536 was described and referred to Kunbarrasaurus. However, the describing authors refrained from referring it to K. leversi because it did not share any unique features with the type specimen. It was found in a layer belonging to the Toolebuc Formation, which directly underlies the Allaru Mudstone and dates to the middle-upper Albian. The specimen consists of a partial skull associated with elements from the postcrania. Unfortunately, most of the postcranial skeleton remains in limestone and therefore not ready for description.[4]

Description

[edit]

Kunbarrasaurus was a small quadrupedal armoured dinosaur. Its length has been estimated at 2.5–3.5 metres (8.2–11.5 ft).[1][5]

In 2015, some distinguishing traits of the skull of Kunbarrasaurus were established. The roof of the skull is almost perfectly flat, apart from a limited convex profile of the postorbital bone and the nasal bone. The edges of the skull top, formed by the prefrontal, supraorbital and postorbital bones, make a right angle with the skull sides. The supraorbital is made up of one bone instead of two or three. The prefrontal is only exposed on the skull roof and does not reach the eye socket. The nasal bone does not reach the snout side and is limited to the snout top and the large, more centrally placed, opening around the nostril. This opening, which is completely located in the nasal bone, is large compared to the maxillary part of the snout and fully accessible from above and the side. The maxilla vertically attains the full height of the skull, reaching to the prefrontal on the skull roof. The hindmost tooth is positioned under the rear edge of the eye socket.[2]

The lacrimal bone is directed vertically. The pterygoid bones do not touch each other with their rear ends at the braincase, totally separated by the basisphenoid. The quadrate is vertically oriented. The coronoid process of the lower jaw is strongly protruding. The side of the braincase largely consists of cartilage instead of bone, so that many brain nerves must have had their exits in a single large opening, rather than separate small ones. The inner ear is very large compared with the skull as a whole and differs from that of all other known Dinosauria in the ear vestibule not being separated from the brain cavity, the floor for the cochlea not being made of bone and the vestibule being so large that the semicircular canals are shortened. The skull osteoderms are flat or at most have a low keel. There are no squamosal or quadratojugal horns or bosses on the upper skull corners or the cheeks.[2]

Osteoderms

[edit]

Kunbarrasaurus had bony protrusions, also known as body armour, in the skin on its head, back, abdomen, legs and along the tail. Several types of armour are known in place in Kunbarrasaurus, including small ossicles, small keeled scutes on the body ordered in parallel longitudinal rows, large scutes without keels on the snout, large keeled scutes on the neck, shoulders, and possibly tail, spike-like scutes on the hips, and a combination of ridged and keeled scutes and triangular plates on the tail. There was one preserved ring of scutes around the neck. A sacral shield is absent.[6]

The exact arrangement of armour on the tail is unclear, although it appears that there were triangular plates that ran on the sides of the tail, with long scutes forming a row along the top of the tail.[6] While most of the tail is not preserved, some of the relatives of Kunbarrasaurus, including Stegouros and Antarctopelta, had a large macuahuitl-like structure at the end of the tail, formed by expanded triangular flattened osteoderms.[5][7]

Phylogeny

[edit]

Kunbarrasaurus was in 2015 placed in the Ankylosauria. The same year Victoria Arbour e.a. had entered QM F1801 and the Minmi holotype as separate operational taxonomic units in their analysis. Whereas Minmi was recovered as a basal member of the Ankylosauridae, QM F1801 had a basal position in Ankylosauria, i.e. was too "primitive" to be included in either the Ankylosauridae or Nodosauridae.[8] In the 2015 description of Kunbarrasaurus on qualitative considerations such a position was indeed deemed likely.[2]

In 2021, Sergio Soto-Acuña et al. found Kunbarrasaurus to belong to a distinctive basal lineage of Southern Hemisphere ankylosaurs, the Parankylosauria. Their phylogenetic analyses placed it as the sister taxon to the clade formed by the Late Cretaceous Stegouros and Antarctopelta.[5]

Paleobiology

[edit]

As with other ankylosaurians, Kunbarrasaurus was herbivorous. Unlike most herbivorous dinosaurs, there is direct evidence of the diet of Kunbarrasaurus: gut contents are known from the well-preserved nearly complete holotype specimen, found in the abdominal cavity in front of the left ilium.

Diet

[edit]The gut contents consist of fragments of fibrous or vascular plant tissue, fruiting bodies, spherical seeds, and vesicular tissue (possibly from fern sporangia). The most common remains are the fibrous or vascular fragments, which are typically rather uniform in size at 0.6 to 2.7 millimetres (0.024 to 0.106 inches) long and have clean cuts at their ends, perpendicular to a given fragment's long axis. Because of the small size of the fragments, they have been interpreted as having been nibbled from plants or chopped in the mouth, evidence of some method of retaining food in the mouth. These small fragments may have come from twigs or stems, but their size is more suggestive of vascular bundles in leaves. The clean cuts and lack of gastroliths suggest that the animal relied on oral processing instead of gastroliths or grit to grind food. The seeds (0.3 mm [0.01 in] across) and fruiting bodies (4.5 mm [0.18 in] across) were apparently swallowed whole. Comparisons with gut contents and scat from other modern herbivores like lizards, emus, and geese indicate that this Kunbarrasaurus individual had a more sophisticated process for cutting up plant material.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Molnar, Ralph E. (1996). "Preliminary report a new ankylosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Queensland, Australia" (PDF). Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 39: 653–668.

- ^ a b c d e f Lucy G. Leahey; Ralph E. Molnar; Kenneth Carpenter; Lawrence M. Witmer; Steven W. Salisbury (2015). "Cranial osteology of the ankylosaurian dinosaur formerly known as Minmi sp. (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Lower Cretaceous Allaru Mudstone of Richmond, Queensland, Australia". PeerJ. 3: e1475. doi:10.7717/peerj.1475. PMC 4675105. PMID 26664806.

- ^ "The Open Access Dinosaurs of 2015". PLOS Paleo.

- ^ Frauenfelder, Timothy G.; Bell, Phil R.; Brougham, Tom; Bevitt, Joseph J.; Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Kear, Benjamin P.; Wroe, Stephen; Campione, Nicolás E. (2022-03-28). "New Ankylosaurian Cranial Remains From the Lower Cretaceous (Upper Albian) Toolebuc Formation of Queensland, Australia". Frontiers in Earth Science. 10. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.803505. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ a b c Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O.; Kaluza, Jonatan; Leppe, Marcelo A.; Botelho, Joao F.; Palma-Liberona, José; Simon-Gutstein, Carolina; Fernández, Roy A.; Ortiz, Héctor; Milla, Verónica; Aravena, Bárbara (2021-12-01). "Bizarre tail weaponry in a transitional ankylosaur from subantarctic Chile". Nature. 600 (7888): 259–263. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..259S. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04147-1. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34853468. S2CID 244799975.

- ^ a b Molnar, Ralph E. (2001). "Armor of the small ankylosaur Minmi". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 341–362. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ Soto Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O.; Kaluza, Jonatan (2024). "A new look at the first dinosaur discovered in Antarctica: reappraisal of Antarctopelta oliveroi (Ankylosauria: Parankylosauria)". Advances in Polar Science. 35 (1): 78–107. doi:10.12429/j.advps.2023.0036.

- ^ Arbour VM, Currie PJ. 2015. Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosauriddinosaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

- ^ Molnar, Ralph E.; Clifford, H. Trevor (2001). "An ankylosaurian cololite from Queensland, Australia". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 399–412. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.