Kalīla wa-Dimna

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Arabic. (April 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

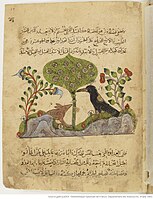

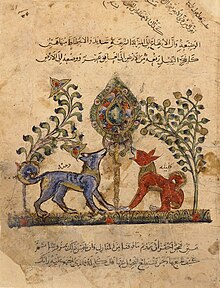

The two jackals of the title, Kalila and Dimna. Arabic illustration, 1220 | |

| Author | Unknown (originally Sanskrit, translated by Ibn al-Muqaffa') |

|---|---|

| Original title | كليلة ودمنة |

| Translator | Ibn al-Muqaffa' |

| Language | Arabic, Middle Persian |

| Subject | Fables |

| Genre | Beast fable |

| Published | 8th century (Arabic translation) |

| Publication place | Abbasid Caliphate |

| Media type | Manuscript |

Kalīla wa-Dimna or Kelileh o Demneh (Arabic: كليلة ودمنة; Persian: کلیله و دمنه) is a collection of fables. The book consists of fifteen chapters containing many fables whose heroes are animals. A remarkable animal character is the lion, who plays the role of the king; he has a servant ox Shetrebah, while the two jackals of the title, Kalila and Dimna, appear both as narrators and as protagonists. Its likely origin is the Sanskrit Panchatantra. The book has been translated into many languages, with surviving illustrations in manuscripts from the 13th century onwards.

Origins

[edit]The book is based on the c. 200 BC Sanskrit text Panchatantra. It was translated into Middle Persian in the sixth century by Borzuya.[1][2][3] It was subsequently translated into Arabic in the eighth century by the Persian Ibn al-Muqaffa'.[4] King Vakhtang VI of Kartli made a translation from Persian to Georgian in the 18th century.[5] His work, later edited by his mentor Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, has been used as a reference while determining the possible original text, along with an earlier unfinished translation by King David I of Kakheti.[6]

Synopsis

[edit]The King Dabschelim is visited by the philosopher Bidpai who tells him a collection of stories of anthropomorphised animals with important morals for a King. The stories are in response to requests of parables from Dabschelim and they follow a Russian doll format, with stories interwoven and nested to some depth. There are fifteen main stories, acting as frame stories with many more stories within them. The two jackals, Kalila and Dimna, feature both as narrators of the stories and as protagonists within them. They work in the court of the king, Bankala the lion. Kalila is happy with his lot, whereas Dimna constantly struggles to gain fame. The stories are allegories set in a human social and political context, and in the manner of fables illustrate human life.

Manuscripts

[edit]Manuscripts of the text have for many centuries and translated into other languages contained illustrations to accompany the fables.

c.1220 edition (BNF Arabe 3465)

[edit]This edition of Kalīla wa-Dimna is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF Arabe 3465).[7] It dates to the first quarter of the 13th century (usually dated c.1220 CE).[7]

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Arabe 3465, folio 34r. Frontispiece.[8]

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Arabe 3465, folio 86r. Animal scene

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Arabe 3465, folio 95v. Animal scene

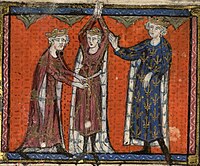

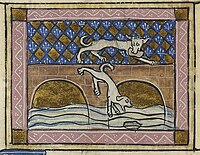

1313 edition (BNF Latin 8504)

[edit]French translation of Kalila wa Dimna, Raymond de Béziers, dated to 1313 CE. Now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF Latin 8504).[10]

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Latin 8504. Ruler: Philip IV and family.

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Latin 8504. Regnal scene

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Latin 8504, folio 23v. Animal scene.

-

Kalila wa Dimna BNF Latin 8504, folio 26r. Animal scene.

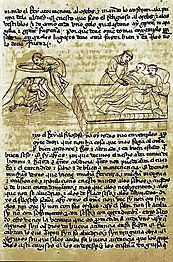

Other editions

[edit]-

Spanish manuscript, workshop of Frederick of Castile, 1251–1261

-

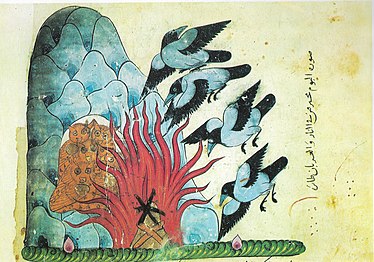

The crows and the owls. Syrian painter, c. 1300–1325

-

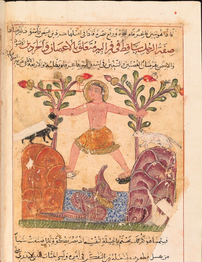

The jackals Kalila and Dimna look on as the snake and the elephant fight. Arabic, 1340

-

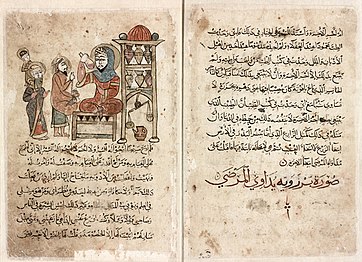

"Barzueh heals the sick". 1346–1347

-

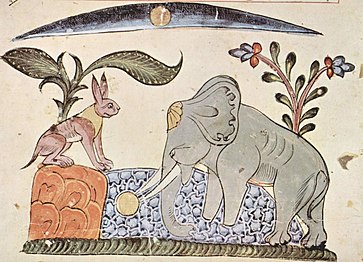

Hare fools Elephant by showing the moon's reflection. Arabic, 1354

-

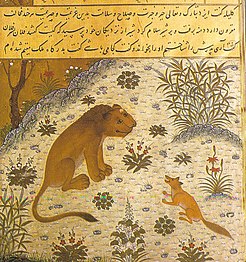

The turtle and the monkey. Persian, Timurid school, c. 1410–1420

-

A page from a Persian manuscript, dated 1429

-

The lion eats the bull, as the two jackals look on. Painted in Herat, 1430

-

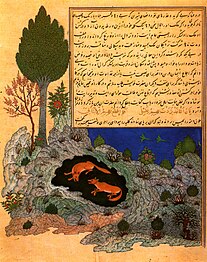

The jackals Kalila and Dimna in their den. Herat school, 1431

-

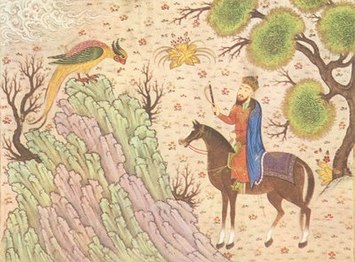

Fanzah refuses to return to the King. Probably made for Pir Budaq, Baghdad?, c. 1460

-

"Kalila and Dimna Discussing Dimna's Plans to Become a Confidante of the Lion". 18th century

-

Armenian translation of The story of seven sages, 1740

Legacy

[edit]Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the Middle Persian manuscript of Kalila and Dimna is considered a masterpiece of Arabic and world literature.[11][12] In 1480, Johannes Gutenberg published Anton von Pforr's German version, Buch der Beispiele der alten Weisen. La Fontaine, in the preface to his second collection of Fables, explicitly acknowledged his debt to "the Indian sage Pilpay".[13] The collection has been adapted in plays,[14][15][16] cartoons,[17] and commentary works.[18][19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (3 November 2021). "Translations of Historical Works from Middle Persian into Arabic". Quaderni di Studi Arabi. 16 (1–2): 42–60. doi:10.1163/2667016X-16010003. ISSN 2667-016X. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "About Kalila wa-Dimna". Kalila. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Kinoshita, Sharon (2008). "Translation, empire, and the worlding of medieval literature: the travels of Kalila wa Dimna". Postcolonial Studies. 11 (4): 371–385. doi:10.1080/13688790802456051.

- ^ "Kalila and Dimna". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Ვახტანგ VI. Საქართველოს ილუსტრირებული ისტორია. პალიტრა L. 2015. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Dakabadonebuli Qilila da damana" (PDF). Ilia State University, Georgia. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Consultation". archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr.

- ^ Contadini 2012, Plate 8.

- ^ Stillman, Yedida K. (2003). Arab dress: a short history; from the dawn of Islam to modern times (Rev. 2. ed.). Brill. p. Plate 30. ISBN 978-90-04-11373-2.

- ^ "Consultation". archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr.

- ^ "World Digital Library, Kalila and Dimna". Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Kalila wa-Dimna – Wisdom Encoded". 7 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Paul Lunde article in Saudi Aramco World, 1972". Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Kalila wa Dimna play for Children held in Bahrain, 2003". Archived from the original on 5 August 2016.

- ^ "Kalila wa Dimna play for children held in Jerusalem".

- ^ "Kalila wa Dimna play held in Tunisia, 2016". Archived from the original on 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Kalila wa Dimna cartoon series debut on Al-Jazeera kids, 2006". Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ ""The Wisdom of Kalila wa Dimna" book launch by prominent Palestinian writer, 2016". Archived from the original on 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Signing of a Kalila wa Dimna commentary work by prominent Jordanian writer, 2011". 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Contadini, Anna (1 January 2012). A World of Beasts: A Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Arabic Book on Animals (the Kitāb Na't al-Ḥayawān) in the Ibn Bakhtīshū' Tradition. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004222656_005.

Further reading

[edit]- D’Anna, Luca; Benkato, Adam (2024). "On Middle Persian Interference in Early Arabic Prose: The Case of Kalīla wa-Dimna". Journal of Language Contact. 16 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1163/19552629-bja10051.

![Kalila wa Dimna BNF Arabe 3465, folio 34r. Frontispiece.[8]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Kalila_wa_Dimna_BNF_Arabe_3465%2C_folio_34r.jpg/154px-Kalila_wa_Dimna_BNF_Arabe_3465%2C_folio_34r.jpg)

![Kalila wa Dimna BNF Arabe 3465, folio 20v. King wearing the aqabā' turkī with uninscribed tiraz armbands.[9]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Kalila_wa_Dimna_BNF_131v_%28king_detail%29.jpg/158px-Kalila_wa_Dimna_BNF_131v_%28king_detail%29.jpg)