Karshapana

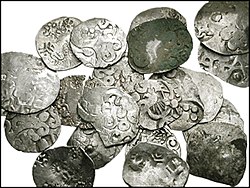

Karshapana (Sanskrit: कार्षापण, IAST: Kārṣāpaṇa), according to the Ashtadhyayi of Panini, refers to ancient Indian coins current during the 6th century BCE onwards,[citation needed] which were unstamped and stamped (āhata) metallic pieces whose validity depended on the integrity of the person authenticating them. It is commonly supposed by scholars that they were first issued by merchants and bankers rather than the state. They contributed to the development of trade since they obviated the need for weighing of metal during exchange. Kārṣāpaṇas were basically silver pieces stamped with one to five or six rūpas ('symbols') originally only on the obverse side of the coins initially issued by the Janapadas and Mahajanapadas, and generally carried minute mark or marks to testify their legitimacy. Silver punch-marked coins ceased to be minted sometime in the second century BCE but exerted a wide influence for next five centuries.[1][2]

Etymology

[edit]The punch-marked coins were called "Kārṣāpaṇa" because they weighed one kārsha each.[3]

History

[edit]The period of the origin of the punch-marked coins is not yet known, but their origin was indigenous.[citation needed]

Literary References

[edit]The word, Kārṣāpaṇa, first appears in the Sutra literature, in the Samvidhān Brāhmana. Coins bearing this name were in circulation during the Sutra and the Brāhmana period and also find a mention in the early Buddhist (Dhammapada verse 186):[4]

- Na kahapana vassena titti kamesu vijjati appassada dukha kama iti vinnaya pandito.

- "Not by a shower of coins can sensual desires be satiated; sensual desires give little pleasure and are fraught with evil consequences (dukkha)."

and Persian texts of that period.[citation needed]

Patanjali's mid 2nd century BCE commentary, Mahabhashya, on vārttikas of Kātyāyana, on Pāṇini's, c. 400 BCE, Aṣṭādhyāyī,[5] likely composed at Salatura, in the Achaemenid satrapy of Gandāra, uses the word, "Kārṣāpaṇa", to mean a coin –

- कार्षापणशो ददाति

- "He gives by the Kārṣāpaṇa coin" or

- कार्षापणम् ददाति

- "He gives a Kārṣāpaṇa",

while explaining the use of the suffix – शस् taken up by Pāṇini in Sutra V.iv.43, in this case, कार्षापण + शः to indicate distributivity.[6]

The Shatapatha Brahmana speaks about Kārṣāpaṇas weighing 100 ratis which kind were found buried at Taxila by John Marshall in 1912.

Finds

[edit]The Golakpur (Patna) find pertains to the period of Ajatashatru.[7]

The Bhir Mound finds (1924-1945), at Taxila (present day Pakistan), includes Maurya coins and a coin of Diodotus I (255-239 BCE) issued in 248 BCE.[8]

The, c.380 BCE, Chaman Hazuri hoard (Kabul) includes two varieties of punch-marked Indian coins along with numerous Greek coins of 5th and early 4th centuries BCE,[9] thereby indicating that those kind of Kārṣāpaṇas were contemporaneous to the Greek coins and in circulation as legal tender.[10]

Mauryan Period

[edit]During the Mauryan Period, the punch-marked coin called Rūpyārūpa, which was same as Kārṣāpaṇa or Kahāpana or Prati or Tangka, was made of alloy of silver (11 parts), copper (4 parts) and any other metal or metals (1 part).The early indigenous Indian coins were called Suvarṇa (made of gold), Purāṇa or Dhārana (made of silver) and Kārṣāpaṇa (made of copper). The Golakpur (Patna) find is mainly pre-Maurya, possibly of the Nanda era, and appear to have been re-validated to make them kośa- praveśya (legal tender); the coins bearing larger number of marks are thought to be older in origin. The Maurya Empire was definitely based upon money-economy.[11] The punch-marked copper coins were called paṇa.[12] This type of coins were in circulation much before the occupation of Punjab by the Greeks [13] who even carried them away to their own homeland.[14] Originally, they were issued by traders as blank silver bent-bars or pieces; the Magadha silver punch-marked Kārṣāpaṇa of Ajatashatru of Haryanka dynasty was a royal issue bearing five marks and weighing fifty-four grains, the Vedic weight called kārsha equal to sixteen māshas.[15]

Even during the Harappan Period (ca 2300 BCE) silver was extracted from argentiferous galena. Silver Kārṣāpaṇas show lead impurity but no association with gold.

The internal chronology of Kārṣāpaṇa and the marks of distinction between the coins issued by the Janapadas and the Magadhan issues is not known, the Arthashastra of Kautilya speaks about the role of the Lakshanadhyaksha ('the Superintendent of Mint') who knew about the symbols and the Rupadarshaka ('Examiner of Coins'), but has remained silent with regard to the construction, order, meaning and background of the punched symbols on these coins hence their exact identification and dating has not been possible.[16]

The term Kārṣhāpaṇa referred to gold, silver and copper coins weighing 80 ratis or 146.5 grains; these coins, the earliest square in shape, followed the ancient Indian system of described in Manu Smriti.[17] Use of money was known to Vedic people much before 700 BCE. The words, Nishka and Krishnala, denoted money, and Kārṣāpaṇas, as standard coins, were regularly stored in the royal treasuries.[18]

The local silver punch-marked coins, included in the Bhabhuā and Golakpur finds, were issued by the Janapadas and were in circulation during the rule of the Brihadratha dynasty which was succeeded by the Haryanka dynasty in 684 BCE; these coins show four punch-marks - the sun-mark, the six-armed symbol, arrows (three) and taurine (three) which were current even during the rule of Bimbisara (c. 492-c.460 BCE). Ajatashatru (552-520 BCE) issued the first Imperial coins of six punch-marks with the addition of the bull and the lion. The successors of Ajatashatru who ruled between 520 and 440 BCE and the later Shishunaga dynasty and the Nanda dynasty issued coins of five symbols – the sun-mark, the six-armed symbol and any three of the 450 symbols. The Maurya coins also have five symbols – the sun-mark, the six-armed symbol, three-arched hill with a crescent at the top, a branch of a tree at the corner of a four-squared railing and a bull with taurine in front. Punch-marked copper coins were first issued during the rule of Chandragupta Maurya or Bindusara.

Numismatic study

[edit]While subcontinental punchmarked coins were initially ignored by Western numimastics, British colonial administrators James Princep and Alexander Cunningham published initial findings in the 19th century. Indian numismatists followed with a deeper examination of karshapana, notably Durga Prasad, D.D. Kosambi,[19] A.S. Altekar, and Parmeshwari Lal Gupta.[20] Gupta and Hardaker's Punchmarked coinage of the Indian subcontinent: Magadha-Mauryan series, last updated in 2014, is the most complete catalog of karshapana for those issuers but does not include other ancient punchmarked coins.[21]

Gupta and Hardaker classify punchmarked coins into nine series (0-VIII), analyze evidence from eleven "hoards" (buried coin deposits), and present illustrated tables of 625 unique marks found on the coins, and an illustrated catalog of 649 coin types. By careful consultation of this reference, most silver punchmarked coins can be identified.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Parmeshwari Lal Gupta. Coins. National Book Trust. pp. 7–11. Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- ^ Ghosh, Amalananda (1990), An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, BRILL, p. 10, ISBN 90-04-09264-1

- ^ A.V.Narsimha Murthy (1975). The Coins of Karnataka. Geetha Book House. p. 19.

- ^ "The Dhammapada: Verses and Stories". www.tipitaka.net. Archived from the original on 2022-11-26. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- ^ Scharf, Peter M. (1996). The Denotation of Generic Terms in Ancient Indian Philosophy: Grammar, Nyāya, and Mīmāṃsā. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-863-6.

- ^ The Ashtadhyayi of Panini Vol.2. Motilal Banarsidass. 1962. p. 998. ISBN 9788120804111.

- ^ Anand Singh (1995). Bhārat kī prāchīn mudrāyen (Ancient coins of India) 1998 Edition. Sharda Pustak Bhavan, Allahabad. pp. 41–42. ISBN 8186204091.

- ^ Parmeshwari Lal Gupta. Coins. National Book Trust. pp. 17–20, 239–240. Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- ^ Bopearachchi & Cribb, Coins illustrating the History of the Crossroads of Asia 1992, pp. 57–59: "The most important and informative of these hoards is the Chaman Hazouri hoard from Kabul discovered in 1933, which contained royal Achaemenid sigloi from the western part of the Achaemenid Empire, together with a large number of Greek coins dating from the fifth and early fourth century BC, including a local imitation of an Athenian tetradrachm, all apparently taken from circulation in the region."

- ^ Recording the Progress of Indian History. Primus Books. 2012. ISBN 9789380607283.

- ^ Radhakumud Mookerji (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and his times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 106, 107, 215, 212. ISBN 9788120804050.

- ^ Indian Sculpture. University of California Press. January 1986. p. 67. ISBN 9780520059917.

- ^ Alexander Cunnigham (December 1996). Coins of Ancient India. Asian Educational Services. p. 47. ISBN 9788120606067.

- ^ Frank L. Holt (2005). Into the Land of Bones. University of California Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780520245532.

karshapana.

- ^ D.D.Kosambi (1994). The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline. p. 124,129. ISBN 9780706986136.

- ^ hari C. Bhardwaj (1979). Aspects of Ancient Indian Technology. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 140, 142. ISBN 9788120830400. Archived from the original on 2024-01-31. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ S.N.Naskar (1996). Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture. Abhinav Publications. p. 186, 203. ISBN 9788170172987. Archived from the original on 2024-01-31. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ D.R.Bhandarkar (1990). Lectures on Ancient Indian Numismatics. Asian Educational Services. pp. 55, 62, 79. ISBN 9788120605497. Archived from the original on 2024-01-31. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ Kosambi, D.D. 1948-1949. Chronological order of punchmarked coins I. Journal of the Bengal Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24-25, pp. 33-48.

- ^ Gupta, P.L. 1955. A bibliography of the hoards of punchmarked coins of ancient India. Numismatic Society of India. Monograph 2. Varanasi.

- ^ Gupta, P.L. & T. Hardaker. 2014. Punchmarked Coins of the Indian Subcontinent: Magadha-Mauryan Series. IIRNS Publication. Mumbai.

- ^ Gupta, P.L. & T. Hardaker. 2014. Punchmarked Coins of the Indian Subcontinent: Magadha-Mauryan Series. IIRNS Publication. Mumbai.

Sources

[edit]- Bopearachchi, Osmund; Cribb, Joe (1992), "Coins illustrating the History of the Crossroads of Asia", in Errington, Elizabeth; Cribb, Joe; Claringbull, Maggie (eds.), The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan, Ancient India and Iran Trust, pp. 57–59, ISBN 978-0-9518399-1-1