Islamic attitudes towards science

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

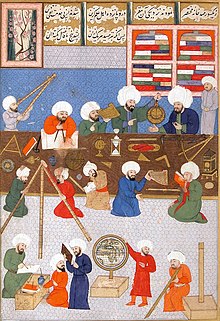

Muslim scholars have developed a spectrum of viewpoints on science within the context of Islam.[1] Scientists of medieval Muslim civilization (e.g. Ibn al-Haytham) contributed to the new discoveries in science.[2][3][4] From the eighth to fifteenth century, Muslim mathematicians and astronomers furthered the development of mathematics.[5][6] Concerns have been raised about the lack of scientific literacy in parts of the modern Muslim world.[7]

Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially medicine, mathematics, astronomy, agriculture as well as physics, economics, engineering and optics.[8][9][10][11][12]

Aside from these contributions, some Muslim writers have made claims that the Quran made prescient statements about scientific phenomena as regards to the structure of the embryo, the solar system, and the development of the universe.[13][14]

Terminology

[edit]According to Toby Huff, there is no true word for science in Arabic as commonly defined in English and other languages. In Arabic, "science" can simply mean different forms of knowledge.[15] This view has been criticized by other scholars. For example, according to Muzaffar Iqbal, Huff's framework of inquiry "is based on the synthetic model of Robert Merton who had made no use of any Islamic sources or concepts dealing with the theory of knowledge or social organization"[5] Each branch of science has its own name, but all branches of science have a common prefix, ilm. For example, physics is more literally translated from Arabic as "the science of nature", علم الطبيعة ‘ilm aṭ-ṭabī‘a; arithmetic as the "science of accounts" علم الحساب ilm al-hisab.[16] The religious study of Islam (through Islamic sciences like Quranic exegesis, hadith studies, etc.) is called العلم الديني "science of religion" (al-ilm ad-dinniy), using the same word for science as "the science of nature".[16] According to the Hans Wehr Dictionary of Arabic, while علم’ ilm is defined as "knowledge, learning, lore," etc. the word for "science" is the plural form علوم’ ulūm. (So, for example, كلية العلوم kullīyat al-‘ulūm, the Faculty of Science of the Egyptian University, is literally "the Faculty of Sciences ...")[16]

History

[edit]Classical science in the Muslim world

[edit]

One of the earliest accounts of the use of science in the Islamic world is during the eighth and sixteenth centuries, known as the Islamic Golden Age.[17] It is also known as "Arabic science" because of the majority of texts that were translated from Greek into Arabic. The mass translation movement, that occurred in the ninth century allowed for the integration of science into the Islamic world. The teachings from the Greeks were now translated and their scientific knowledge was now passed on to the Arab world. Despite these conditions, not all scientists during this period were Muslim or Arab, as there were a number of notable non-Arab scientists (most notably Persians), as well as some non-Muslim scientists, who contributed to scientific studies in the Muslim world.

A number of modern scholars such as Fielding H. Garrison, Sultan Bashir Mahmood, Hossein Nasr consider modern science and the scientific method to have been greatly inspired by Muslim scientists who introduced a modern empirical, experimental and quantitative approach to scientific inquiry.[citation needed] Certain advances made by medieval Muslim astronomers, geographers and mathematicians were motivated by problems presented in Islamic scripture, such as Al-Khwarizmi's (c. 780–850) development of algebra in order to solve the Islamic inheritance laws,[18] and developments in astronomy, geography, spherical geometry and spherical trigonometry in order to determine the direction of the Qibla, the times of Salah prayers, and the dates of the Islamic calendar.[19] These new studies of math and science would allow for the Islamic world to get ahead of the rest of the world. ‘With these inspiration at work, Muslim mathematicians and astronomers contributed significantly to the development to just about every domain of mathematics between the eight and fifteenth centuries"[20]

The increased use of dissection in Islamic medicine during the 12th and 13th centuries was influenced by the writings of the Islamic theologian, Al-Ghazali, who encouraged the study of anatomy and use of dissections as a method of gaining knowledge of God's creation.[21] In al-Bukhari's and Muslim's collection of sahih hadith it is said: "There is no disease that God has created, except that He also has created its treatment." (Bukhari 7-71:582). This culminated in the work of Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), who discovered the pulmonary circulation in 1242 and used his discovery as evidence for the orthodox Islamic doctrine of bodily resurrection.[22] Ibn al-Nafis also used Islamic scripture as justification for his rejection of wine as self-medication.[23] Criticisms against alchemy and astrology were also motivated by religion, as orthodox Islamic theologians viewed the beliefs of alchemists and astrologists as being superstitious.[24]

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his Matalib, discusses Islamic cosmology, criticizes the Aristotelian notion of the Earth's centrality within the universe, and "explores the notion of the existence of a multiverse in the context of his commentary," based on the Quranic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." He raises the question of whether the term "worlds" in this verse refers to "multiple worlds within this single universe or cosmos, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." On the basis of this verse, he argues that God has created more than "a thousand thousand worlds (alfa alfi 'awalim) beyond this world such that each one of those worlds be bigger and more massive than this world as well as having the like of what this world has."[25] Ali Kuşçu's (1403–1474) support for the Earth's rotation and his rejection of Aristotelian cosmology (which advocates a stationary Earth) was motivated by religious opposition to Aristotle by orthodox Islamic theologians, such as Al-Ghazali.[26][27]

According to many historians, science in the Muslim civilization flourished during the Middle Ages, but began declining at some time around the 14th[28] to 16th[17] centuries. At least some scholars blame this on the "rise of a clerical faction which froze this same science and withered its progress."[29] Examples of conflicts with prevailing interpretations of Islam and science – or at least the fruits of science – thereafter include the demolition of Taqi al-Din's great Constantinople observatory in Galata, "comparable in its technical equipment and its specialist personnel with that of his celebrated contemporary, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe." But while Brahe's observatory "opened the way to a vast new development of astronomical science," Taqi al-Din's was demolished by a squad of Janissaries, "by order of the sultan, on the recommendation of the Chief Mufti," sometime after 1577 CE.[29][30]

Science and religious practice

[edit]Scientific methods have been historically applied to find solutions to the technical exigencies of Islamic religious rituals, which is a characteristic of Islam that sets it apart from other religions. These ritual considerations include a lunar calendar, definition of prayer times based on the position of the sun, and a direction of prayer set at a specific location. Scientific methods have also been applied to Islamic laws governing the distribution of inheritances and to Islamic decorative arts. Some of these problems were tackled by both medieval scientists of the Islamic world and scholars of Islamic law. Though these two groups generally used different methods, there is little evidence of serious controversy between them on these subjects, with the exception of the criticism leveled by religious scholars at the methods of astronomy due to its association with astrology.[31]

Modern science in the Muslim world

[edit]At the beginning of the nineteenth century, modern science arrived in the Muslim world, bringing with it "the transfer of various philosophical currents entangled with science" including schools of thought such as Positivism and Darwinism. This had a profound effect on the minds of Muslim scientists and intellectuals and also had a noticeable impact on some Islamic theological doctrines.[32]

While the majority of Muslim scientists tried to adapt their understanding of Islam to the findings of modern science, some rejected modern science as "corrupt foreign thought, considering it incompatible with Islamic teachings", others advocated for the wholesale replacement of religious worldviews with a scientific worldview, and some Muslim philosophers suggested separating the findings of modern science from its philosophical attachments.[33] Among the majority of Muslim thinkers, a key justification for the use of modern science was the benefits that modern knowledge clearly brought to society. Others concluded that science could ultimately be reconciled with faith. A further apologetic trend saw the emergence of theories that scientific discoveries had been predicted in the Quran and Islamic tradition, thereby internalizing science within religion.[33]

According to 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center asking Muslims in different Muslim majority countries in the Middle East and North Africa if there was a conflict between science and religion few agreed in Morocco (18%), Egypt (16%), Iraq (15%), Jordan (15%) and the Palestinian territories (14%). More agreed in Albania (57%), Turkey (40%), Lebanon (53%) and Tunisia (42%).[34]

The poll also found a variance in how Muslim population in some countries are at odds with current scientific theories about biological evolution and the origin of man.[34] Only four of the 22 countries surveyed that at least 50% of the Muslims surveyed rejected evolution (Iraq 67%, Tajikistan 55%, Indonesia 55%, Afghanistan 62%). Countries with relatively low rates of disbelief in evolution (i.e. agreeing to the statement "humans and other living things have always existed in present form") include Lebanon (21%), Albania (24%), Kazakhstan (16%).[35]

As of 2018, three Muslim scientists have won a Nobel Prize for science (Abdus Salam from Pakistan in physics, Ahmed Zewail from Egypt and Aziz Sancar from Turkey in Chemistry). According to Mustafa Akyol, the relative lack of Muslim Nobel laureates in sciences per capita can be attributed to more insular interpretations of the religion than in the golden age of Islamic discovery and development, when Islamic society and intellectuals were more open to foreign ideas.[36] Ahmed Zewail who won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and is known as the father of femtochemistry said that "There is nothing fundamental in Islam against science."[37]

Conflict with religion

[edit]The conflicts between Islam and science can become quite complicated. It has been argued that "Muslims must be able to maintain the traditional Islamic intellectual space for the legitimate continuation of the Islamic view of the nature of reality to which Islamic ethics corresponds, without denying the legitimacy of modern science within their own confines".[38] While the natural sciences have not been "fully institutionalized" in predominantly Islamic countries, engineering is considered an applied science that can function in conjunction with religion, and it is one of the most popular career choices of Middle Eastern students.[39] Islamic scholar Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi has noted that important technological innovations—once "considered to be bizarre, strange, haram (religiously forbidden), bidʻah (innovation), against the tradition" in the Muslim world, were later accepted as "standard".

An issue for accepting scientific knowledge rises from the supposed origin: For Muslims, knowledge comes from God, not from human definition of forms of knowledge. An example of this in the Islamic world is that of modern physics, which is considered to be Western instead of an international study. Islamic values claim that "knowledge of reality [is] based not on reason alone, but also on revelation and inspiration".[38]

A passage in the Quran encourages congruency with the truth attained by modern science: "hence they should be both in agreement and concordant with the findings of modern science".[40] This passage was used more often during the time where "modern science" was full of different discoveries. However, many scientific thinkers through the Islamic word still take this passage to heart when it comes to their work. There are also some strong believers that modern viewpoints, such as social Darwinism, challenged all medieval world views, including that of Islam. Some did not even want to be affiliated with modern science, and thought it was just an outside look into Islam.[40] Many followers tend to see problems regarding the integration of Islam with science, and there are many that still stand by the viewpoints of Ahmad ibn Hanbal, that the pursuit of science is still the pursuit of knowledge:

One of the main reasons the Muslim world was held behind when Europe continued its ascent was that the printing press was banned. And there was a time when the Ottoman Sultan issued a decree that anybody caught with a printing press shall be executed for heresy, and anybody who owns a printed book shall basically be thrown into jail. And for 350 years when Europe is printing, when [René] Descartes is printing, when Galileo is printing, when [Isaac] Newton is printing, the only way you can get a copy of any book in the Arab world is to go and hand write it yourself.[41]

The reluctance of the Muslim world to embrace science is manifest in the disproportionately small amount of scientific output, as measured by citations of articles published in internationally circulating science journals, annual expenditures on research and development, and numbers of research scientists and engineers.[42] Concerns have been raised that the contemporary Muslim world suffers from scientific illiteracy.[7] Skepticism of science among some Muslims is reflected in issues such as the resistance in Muslim northern Nigeria to polio inoculation, which some believe is "an imaginary thing created in the West or it is a ploy to get us to submit to this evil agenda."[43] In Pakistan, a small number of post-graduate physics students have been known to blame earthquakes on "sinfulness, moral laxity, deviation from the Islamic true path", while "only a couple of muffled voices supported the scientific view that earthquakes are a natural phenomenon unaffected by human activity."[7]

In the early twentieth century, Iranian Shia Ulama[who?] forbade the learning of foreign languages and the dissection of human bodies in the medical school in Iran.[44] On the other hand, contrary to the current cliché concerning the opposition of the Imamate Shiite Ulama to modern astronomy in the nineteenth century, there is no evidence showing their literal or explicit objection to modern astronomy based on Islamic doctrines. They showed themselves the advocates of modern astronomy with the publication of Hibat al-Dīn Shahristānī's al-Islām wa al-Hayʾa (Islam and Astronomy) in 1910. After that, Shia ulama not only were not against the modern astronomy but also believed that the Quran and Islamic hadiths admit it.[45]

During the twentieth century, the Islamic world introduction to modern science was facilitated by the expansion of educational systems. For example, in 1900 and 1925, Istanbul and Cairo opened universities. In these universities, new concerns have emerged among the students. One major issue was naturalism and social Darwinism, which challenged some beliefs. On the other hand, there were efforts to harmonize science with Islam. An example is the nineteenth-century study of Kudsî of Baku, who made connections between his discoveries in astronomy and what he knew from the Quran. These included "the creation of the universe and the beginning of like; in the second part, with doomsday and the end of the world; and the third was the resurrection after death".[46]

Late Ottoman Empire and Turkey

[edit]Ahmet Hamdi Akseki, supported by the official institute for religious affairs in Turkey (Diyanet), published various articles about the creation of humanity. He emphazises that the purpose of the Quran is to offer parables and moral lessons, not offering scientific data or accounts of history. To demonstrate the ambiguity of the Islamic tradition in regards to the Earth's age he brings forth several narratives embedded in Islamic exegesis.

First, he recounts several narratives about creatures preceding the creation of Adam. Such species include hinn, binn, timm, rimm. A second one adds the belief that, before God has created Adam, thirty previous races were created, each with a gap of thousand years in between. During that time, the earth has been empty, until a new creation began to be formed. Lastly, he offers a dialogue between the Andalusian scholar ibn Arabi and a strange man:

During his visit to Mecca, he came across a person in strange cloths. When he asked the identity of the strange man, the man said: "I am from your ancient ancestors. I died forty thousand years ago!" Bewildered by this response, Ibn al-‘Arabı¯ asked, "What are you talking about? Books narrate that Adam was created about six thousand years ago." The man replied "What Adam are you talking about? Beware of the fact that there were a hundred thousand Adams before Adam, your ancestor."[47]

The latter, so Akseki, underlines that the idea of Young Earth creationism is a challenge of the Judeo-Christian tradition. He admits that material of a young earth does exists among Muslim commentators, as in the case of ibn Arabi himself, but these are used as supplementary materials borrowed from Jewish sources (Isra'iliyyat) and are not part of the Islamic canon.[48]

Süleyman Ateş, who was president of the Directorate of Religious Affairs in 1976-1978 and issued a tafsir (Interpretation of the Quran), employed similar arguments to that of Aksesi, while using references to Quranic verses to support his arguments.[49] Pointing at 32:7, stating "He began the creation of man from clay.", he points out that humanity was not, in contrast to the Biblical interpretation, created an instant, but emerged as a process.[50] To further support his argument to be in line with Islamic tradition, rather than a secular one, he looked at the Islamic heritage of previous scholars evoking the idea of an evolutionary process, such as the 9th century theologian Jahiz and the 18th century Turkish scholar İbrahim Hakkı Erzurumi, both utilized as references of pre-Darwinian accounts of evolution.[51]

Hasan Karacadağ in his movie Semum, features the trope of conflict between science and religion.[52] When the victim of the movie (Canan) is possessed by a demon, her husband brings her to a psychiatrist (Oğuz) and later to an excorcist (Hoca). A discussion starts between them, those practise is more beneficial to help Canan. While the psychiatrist symbolizes an anti-theistic attitude, Hoca represents a most faithful believer. The psychiatrist calls the Hoca a charlatan and dismisses his belief-system entire, while the Hoca affirms the validity of science, but asserts that science is limited to the knowable world, thus impotent in supernatural matters (i.e. the "unknown"). The Hoca, by his reconciling approach, is depicted as superior, when the demonic cause of Canan's illness is shown. Yet, the film makes clear that the psychiatrist does not fail on behalf of being a scientist, but by his anti-theistism.[53] Exercised properly, science and religion would go hand in hand. When the director was asked if he himself believes in the existence of demons, he said that in such a "chaotic space" it is unlikely that humans are alone. His popular cultural depiction of demons might be seen as a representation of what lies beyond the limits of science, Islam being a tool to guide people to the unknown and unexplainable.[54]

Islamist movements

[edit]Islamist author Muhammad Qutb (brother, and promoter, of Sayyid Qutb) in his influential book Islam, the misunderstood religion, states that "science is a powerful instrument" to increase human knowledge but has become a "corrupting influence on men's thoughts and feelings" for much of the world's population, steering them away from "the Right Path". As an example, he gives the scientific community's disapproval of claims of telepathy, when he claims that it is documented in hadith that Caliph Umar prevented commander Sariah from being ambushed by communicating with him telepathically.[55] Muslim scientists and scholars have subsequently developed a spectrum of viewpoints on the place of scientific learning within the context of Islam.[1]

Until the 1960s, Saudi Sunni ulama opposed any attempts at modernisation, considering them as innovations (bidah). They opposed the spread of electricity, radios, and TVs. As recently as 2015, Sheikh Bandar al-Khaibari rejected the fact that the Earth orbits the Sun, instead claiming that the Earth is "stationary and does not move".[56] In Afghanistan, Sunni Taliban have turned secular schools into Islamic madrasas, valuing religious studies over modern science.[57]

Science and the Quran

[edit]| Quran |

|---|

Many Muslims agree that doing science is an act of religious merit, even a collective duty of the Muslim community.[58] According to M. Shamsher Ali, there are around 750 verses in the Quran dealing with natural phenomena. According to the Encyclopedia of the Quran, many verses of the Quran ask mankind to study nature, and this has been interpreted to mean an encouragement for scientific inquiry,[59] and the investigation of the truth.[59][additional citation(s) needed] Some include, "Travel throughout the earth and see how He brings life into being" (Q29:20), "Behold in the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the alternation of night and day, there are indeed signs for men of understanding ..." (Q3:190)

Mohammad Hashim Kamali has stated that "scientific observation, experimental knowledge and rationality" are the primary tools with which humanity can achieve the goals laid out for it in the Quran.[60] Ziauddin Sardar argues that Muslims developed the foundations of modern science, by "highlighting the repeated calls of the Quran to observe and reflect upon natural phenomenon".[61]

The physicist Abdus Salam believed there is no contradiction between Islam and the discoveries that science allows humanity to make about nature and the universe; and that the Quran and the Islamic spirit of study and rational reflection was the source of extraordinary civilizational development. Salam highlights, in particular, the work of Ibn al-Haytham and Al-Biruni as the pioneers of empiricism who introduced the experimental approach, breaking way from Aristotle's influence, and thus giving birth to modern science. Salam differentiated between metaphysics and physics, and advised against empirically probing certain matters on which "physics is silent and will remain so," such as the doctrine of "creation from nothing" which in Salam's view is outside the limits of science and thus "gives way" to religious considerations.[62]

Islam has its own world view system including beliefs about "ultimate reality, epistemology, ontology, ethics, purpose, etc." according to Mehdi Golshani.[33]

Toshihiko Izutsu writes that in Islam, nature is not seen as something separate but as an integral part of a holistic outlook on God, humanity, the world and the cosmos. These links imply a sacred aspect to Muslims' pursuit of scientific knowledge, as nature itself is viewed in the Quran as a compilation of signs pointing to the Divine.[63] It was with this understanding that the pursuit of science, especially prior to the colonization of the Muslim world, was respected in Islamic civilizations.[64]

The astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum argues that the Quran has developed "the concept of knowledge" that encourages scientific discovery.[65] He writes:

The Qur'an draws attention to the danger of conjecturing without evidence (And follow not that of which you have not the (certain) knowledge of... 17:36) and in several different verses asks Muslims to require proofs (Say: Bring your proof if you are truthful 2:111), both in matters of theological belief and in natural science.

Guessoum cites Ghaleb Hasan on the definition of "proof" according the Quran being "clear and strong... convincing evidence or argument." Also, such a proof cannot rely on an argument from authority, citing verse 5:104. Lastly, both assertions and rejections require a proof, according to verse 4:174.[66] Ismail al-Faruqi and Taha Jabir Alalwani are of the view that any reawakening of the Muslim civilization must start with the Quran; however, the biggest obstacle on this route is the "centuries old heritage of tafseer (exegesis) and other classical disciplines" which inhibit a "universal, epistemiological and systematic conception" of the Quran's message.[67] The philosopher Muhammad Iqbal considered the Quran's methodology and epistemology to be empirical and rational.[68]

Guessoum also suggests scientific knowledge may influence Quranic readings, stating that "for a long time Muslims believed, on the basis on their literal understanding of some Qur’anic verses, that the gender of an unborn baby is only known to God, and the place and time of death of each one of us is likewise al-Ghaib [unknown/unseen]. Such literal under-standings, when confronted with modern scientific (medical) knowledge, led many Muslims to realize that first-degree readings of the Quran can lead to contradictions and predicaments."[69]

Islamists such as Sayyid Qutb argue that since "Islam appointed" Muslims "as representatives of God and made them responsible for learning all the sciences,"[70] science cannot but prosper in a society of true Islam. (However, since Muslim majority countries governments have failed to follow the sharia law in its completeness, true Islam has not prevailed and this explains the failure of science and many other things in the Muslim world, according to Qutb.)[70]

Others claim traditional interpretations of Islam are not compatible with the development of science. Author Rodney Stark argues that Islam's lag behind the West in scientific advancement after (roughly) 1500 CE was due to opposition by traditional ulema to efforts to formulate systematic explanation of natural phenomenon with "natural laws." He claims that they believed such laws were blasphemous because they limit "God's freedom to act" as He wishes, a principle enshired in aya 14:4: "God sendeth whom He will astray, and guideth whom He will," which (they believed) applied to all of creation not just humanity.[71]

Taner Edis wrote An Illusion of Harmony: Science and Religion in Islam.[72] Edis worries that secularism in Turkey, one of the most westernized Muslim nations, is on its way out; he points out that the population of Turkey rejects evolution by a large majority. To Edis, many Muslims appreciate technology and respect the role that science plays in its creation. As a result, he says there is a great deal of Islamic pseudoscience attempting to reconcile this respect with other respected religious beliefs. Edis maintains that the motivation to read modern scientific truths into holy books is also stronger for Muslims than Christians.[73] This is because, according to Edis, true criticism of the Quran is almost non-existent in the Muslim world. While Christianity is less prone to see its Holy Book as the direct word of God, fewer Muslims will compromise on this idea – causing them to believe that scientific truths simply must appear in the Quran. However, Edis argues that there are endless examples of scientific discoveries that could be read into the Bible or Quran if one would like to.[73] Edis qualifies that Muslim thought certainly cannot be understood by looking at the Quran alone; cultural and political factors play large roles.[73]

Miracle literature (Tafsir'ilmi)

[edit]Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, the idea of presence of scientific evidence in the Quran became popularized as ijaz (miracle) literature. The genre of interpreting the Quran as revealing scientific truths before mankind's discovery is also known as Tafsir'ilmi. This approach gained much popularity through "Maurice Bucaille", those works have been distributed through Muslim bookstores and websites, and discussed on television programs by Islamic preachers.[74][13] The movement contends that the Quran abounds with "scientific facts" that appeared centuries before their discovery by science and which "could not have been known" by people at the time.[citation needed] By asserting the presence of scientific truths stemming from the Quran, it also overlaps with Islamic creationism. This approach has been rejected by orthodox theologians who argue that the purpose of the Quran is religious guidance and not for proposing scientific theories.[75]

According to author Ziauddin Sardar, the ijaz movement has created a "global craze in Muslim societies", and has developed into an industry that is "widespread and well-funded".[74][13][76] Individuals connected with the movement include Abdul Majeed al-Zindani, who established the Commission on Scientific Signs in the Quran and Sunnah; Zakir Naik, the Indian televangelist; and Adnan Oktar, the Turkish creationist.[74]

Enthusiasts of the movement argue that among the [scientific] miracles found in the Quran are "everything, from relativity, quantum mechanics, Big Bang theory, black holes and pulsars, genetics, embryology, modern geology, thermodynamics, even the laser and hydrogen fuel cells".[74] Zafar Ishaq Ansari terms the modern trend of claiming the identification of "scientific truths" in the Quran as the "scientific exegesis" of the holy book.[77]

An example is the verse: "So verily I swear by the stars that run and hide ..." (Q81:15–16),[78] which proponents claim demonstrates the Quran's knowledge of the existence of black holes; or: "[I swear by] the Moon in her fullness that ye shall journey on from stage to stage" (Q84:18–19) refers, according to proponents, to human flight into outer space.[74]

Embryology in the Quran

[edit]One claim that has received widespread attention and has even been the subject of a medical school textbook widely used in the Muslim world [79] is that several Quranic verses foretell the study of embryology and "provide a detailed description of the significant events in human development from the stages of gametes and conception until the full term pregnancy and delivery or even post partum."[80]

In 1983, an authority on embryology, Keith L. Moore, had a special edition published of his widely used textbook on embryology (The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology), co-authored by a leader of the scientific miracles movement, Abdul Majeed al-Zindani. This edition, The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology with Islamic Additions,[81] interspersed pages of "embryology-related Quranic verse and hadith" by al-Zindani into Moore's original work.[82]

At least one Muslim-born physician (Ali A. Rizvi) studying the textbook of Moore and al-Zindani found himself "confused" by "why Moore was so 'astonished by'" the Quranic references, which Rizvi found "vague", and insofar as they were specific, preceded by the observations of Aristotle and the Ayr-veda,[83] and/or easily explained by "common sense".[79][note 1]

Some of the main verses are

- (Q39:6) God creates us "in the womb of your mothers, creation after creation, within three darknessess," or "three veils of darkness". The "three" allegedly referring to the abdominal wall, the wall of the uterus, and the chorioamniotic membrane.[84][85]

- Verse Q32:9 identifies the order of organ development of the embryo—ears, then eyes, then heart.[86][note 2]

- Verses referring to "sperm drop" (an-nutfa), and to al-3alaqa (translated as "clinging clot" or "leech like structure") in (Q23:13-14); and to "sperm-drop mixture" (an-nuṭfatin amshaajin) in (Q76:2). The miraculousness of these verse is said to come from the resemblance of the human embryo to a leech, and to the claim that "sperm-drop mixture" refers to a mixture sperm and egg.[84][88]

- (Q53:45-46) "And that He creates the two mates—the male and female—from a sperm-drop when it is emitted," allegedly refers to the fact that the sperm contributes X and Y chromosomes that determine the gender of the baby.[84][88]

However,

- The "three darknesses" or three walls (Q39:6) could easily have been observed by cutting open of pregnant mammals, something done by human beings before the revelation of the Quran ("dissections of human cadavers by Greek scientists have been documented as early as the third century BCE").[89][88]

- Contrary to the claims made about Q32:9, ears do not develop before eyes, which do not develop before heart. The heart begins development "at about 20 days, and the ears and eyes begin to develop simultaneously in the fourth week". However, the verse itself does not mention or claim the order of how the embryo will form first in the womb. "Then He proportioned him and breathed into him from His [created] soul and made for you hearing and vision and hearts; little are you grateful."[90][86]

- The embryo may resemble a leech (ala "clinging clot" or "leech like structure" of al-3alaqa in Q23:13-14), but it resembles many things during the eight week course of its development—none for very long.[88]

- While it is generally agreed the Quran mentions sperm (an-nutfa in several verses), "sperm-drop mixture" (an-nuṭfatin amshaajin in Q76:2) of a mixture of sperm and egg is more problematic as nowhere does the Quran mention the Egg cell or ovum—a rather glaring omission in any description of embryo development, as it the ovum the source of more than half the genetic material of the embryo.[86]

- With mention of male sperm but not female egg in the Quran, it seems likely Q53:45-46—"And that He creates the two mates, the male and female, from a sperm-drop when it is emitted"—is talking about the erroneous idea that all genetic material for offspring comes from the male and the mother simply provides a womb for the developing baby (as opposed to the sperm contributing the X and Y chromosomes that determine the gender of the baby). This idea originated with the ancient Greeks and was popular before modern biology developed.[88]

In 2002, Moore declined to be interviewed by The Wall Street Journal on the subject of his work on Islam, stating that "it's been ten or eleven years since I was involved in the Qur'an."[91]

Some researchers have proposed an evolutionary reading of the verses related to the creation of man in the Qur'an and then considered these meanings as examples of scientific miracles.[92]

Criticism

[edit]Critics argue, verses that proponents say explain modern scientific facts, about subjects such as biology, the origin and history of the Earth, and the evolution of human life, contain fallacies and are unscientific.[93][94]

As of 2008, both Muslims and non-Muslims have disputed whether there actually are "scientific miracles" in the Quran. Muslim critics of the movement include Indian Islamic theologian Maulana Ashraf ‘Ali Thanvi, Muslim historian Syed Nomanul Haq, Muzaffar Iqbal, president of Center for Islam and Science in Alberta, Canada, and Egyptian Muslim scholar Khaled Montaser.[95]

Pakistani theoretical physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy criticizes these claims and says there is no explanation that why many modern scientific discoveries such as quantum mechanics, molecular genetics, etc. were discovered elsewhere.[96][95]

Giving the example of the roundness of the earth and the invention of the television,[note 3] a Christian site ("Evidence for God's Unchanging World") complains the "scientific facts" are too vague to be miraculous.[95]

Critics argue that while it is generally agreed the Quran contains many verses proclaiming the wonders of nature,

- it requires "considerable mental gymnastics and distortions to find scientific facts or theories in these verses" (Ziauddin Sardar);[74]

- that the Quran is the source of guidance in right faith (iman) and righteous action (alladhina amanu wa amilu l-salihat) but the idea that it contained "all knowledge, including scientific" knowledge has not been a mainstream view among Muslim scholarship (Zafar Ishaq Ansari);[77][need quotation to verify] and that "Science is ever-changing ... the Copernican revolution overturning polemic models of the universe to Einstein's general relativity overshadowing Newtonian mechanisms".[13] So while "Science is probabilistic in nature" the Quran deals in "absolute certainty". (Ali Talib);[99]

Nidhal Guessoum says that the central issue in the Islam-science discourse is the hierarchical positioning or place of the Quran in the scientific enterprise.[69]

Mustansir Mir argues for a proper approach to Quran with regard to science that allows multiple and multi-level interpretations.[100][101] He writes:

From a linguistic standpoint, it is quite possible for a word, phrase or statement to have more than one layer of meaning, such that one layer would make sense to one audience in one age and another layer of meaning would, without negating the first, be meaningful to another audience in a subsequent age.

See also

[edit]- Quran and miracles

- Relationship between religion and science

- Religious interpretations of the Big Bang theory

- Ahmadiyya views on evolution

- Christianity and science

- Buddhism and science

- Baháʼí views on science

- Education in Islam

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Superstitions in Muslim societies

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ non-Muslim scientists have also found the case for Quranic prescient explanation about embryology lacking. Pharyngula. "Islamic embryology: overblown balderdash". science blogs. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ The site "Miracles of the Quran" quotes four verses:

- It is He Who has created hearing, sight and minds for you. What little thanks you show! (Qur'an 23:78)

- Allah brought you out of your mothers' wombs knowing nothing at all, and gave you hearing, sight and minds so that perhaps you would show thanks. (Qur'an, 16:78)

- Say: "What do you think? If Allah took away your hearing and your sight and sealed up your hearts, what god is there, other than Allah, who could give them back to you?" (Qur'an 6:46)

- We created man from a mingled drop to test him, and We made him hearing and seeing. (Qur'an 76:2)

and further claims that: "The information only recently obtained about the formation of the baby's organs inside the mother's womb is in complete agreement with that revealed in the Qur’an."[87] - ^ Claims of the Quran foretelling the roundness of the earth can be found at Windows of Islam.com, citing as evidence

- verse 39:5 "He created the heavens and earth in truth. He wraps the night over the day and wraps the day over the night and has subjected the sun and the moon, each running [its course] for a specified term".[97]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Seyyed Hossein Nasr. "Islam and Modern Science"

- ^ "The 'first true scientist'". January 4, 2009 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Haq, Syed (2009). "Science in Islam". Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISSN 1703-7603. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ Robert Briffault (1928). The Making of Humanity, pp. 190–202. G. Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ^ a b Iqbal, Muzaffar (2003). Islam and Science. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 140–51. ISBN 978-0754608004.

- ^ Egyptian Muslim geologist Zaghloul El-Naggar quoted in Science and Islam in Conflict| Discover magazine| 06.21.2007| quote: "Modern Europe's industrial culture did not originate in Europe but in the Islamic universities of Andalusia and of the East. The principle of the experimental method was an offshoot of the Islamic concept and its explanation of the physical world, its phenomena, its forces and its secrets." From: Qutb, Sayyad, Milestones, p. 111, https://archive.org/stream/SayyidQutb/Milestones%20Special%20Edition_djvu.txt

- ^ a b c Hoodbhoy, Perez (2006). "Islam and Science – Unhappy Bedfellows" (PDF). Global Agenda: 2–3. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Saliba, George. 1994. A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-8023-7. pp. 245, 250, 256–57.

- ^ King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis. 74 (4): 531–55. doi:10.1086/353360. S2CID 144315162.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y. 1996. "Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century." Pp. 351–99 in Islam and the Challenge of Modernity, edited by S. S. Al-Attas. Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ "Contributions of Islamic scholars to the scientific enterprise" (PDF).

- ^ "The greatest scientific advances from the Muslim world". TheGuardian.com. February 2010.

- ^ a b c d Cook, Michael, The Koran: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, (2000), p. 30

- ^ see also: Ruthven, Malise. A Fury For God. London; New York: Granta (2002), p. 126.

- ^ Huff, Toby (2007). Islam and Science. Armonk, Ny: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. pp. 26–36. ISBN 978-0-7656-8064-8.

- ^ a b c https://giftsofknowledge.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/hans-wehr-searchable-pdf.pdf Searcheable PDF of the Hans Wehr Dictionary (if that doesn't work check https://archive.org/details/HansWehrEnglishArabicDctionarySearchableFormat/page/n607/mode/2up )

- ^ a b Ahmad Y Hassan, Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century

- ^ Gandz, Solomon (1938), "The Algebra of Inheritance: A Rehabilitation of Al-Khuwārizmī", Osiris, 5: 319–91, doi:10.1086/368492, ISSN 0369-7827, S2CID 143683763.

- ^ Gingerich, Owen (April 1986), "Islamic astronomy", Scientific American, 254 (10): 74, Bibcode:1986SciAm.254d..74G, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0486-74, archived from the original on 2011-01-01, retrieved 2008-05-18

- ^ Eisen, Laderman; Huff, Toby. Science, Religion and Society, an Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Controversy: Islam and Science. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc.

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1995), "Attitudes Toward Dissection in Medieval Islam", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 50 (1), Oxford University Press: 67–110, doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67, PMID 7876530

- ^ Fancy, Nahyan A. G. (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame: 232–33, archived from the original on 2015-04-04, retrieved 2008-06-17

- ^ Fancy, Nahyan A. G. (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame: 49–59, 232–33, archived from the original on 2015-04-04, retrieved 2008-06-17

- ^ Saliba, George (1994), A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam, New York University Press, pp. 60, 67–69, ISBN 978-0-8147-8023-7

- ^ Adi Setia (2004), "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on Physics and the Nature of the Physical World: A Preliminary Survey", Islam & Science, 2, archived from the original on 2012-07-10, retrieved 2010-03-02

- ^ Ragep, F. Jamil (2001a), "Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's Motion in Context", Science in Context, 14 (1–2), Cambridge University Press: 145–63, doi:10.1017/s0269889701000060, S2CID 145372613

- ^ F. Jamil Ragep (2001), "Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science", Osiris, 2nd Series, vol. 16, Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions, pp. 49–64, 66–71.

- ^ Islam by Alnoor Dhanani in Science and Religion, 2002, p. 88.

- ^ a b Islamic Technology: An Illustrated History by Ahmad Y. al-Hassan and Donald Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 282.

- ^ Aydin Sayili, The Observatory in Islam and its place in the General History of the Observatory (Ankara: 1960), pp. 289 ff..

- ^ David A. King (2003). "Mathematics applied to aspects of religious ritual in Islam". In I. Grattan-Guinness (ed.). Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences. Vol. 1. JHU Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780801873966.

- ^ Mehdi Golshani, Does science offer evidence of a transcendent reality and purpose?, June 2003

- ^ a b c Mehdi Golshani, Can Science Dispense With Religion?

- ^ a b "Chapter 7: Religion, Science and Popular Culture". Pew Research Center, Religion and Public Life. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Bilgili, Alper (December 2015). "The British Journal for the History of Science V48:4". The British Journal for the History of Science. 48 (4). Cambridge University Press: 565–582. doi:10.1017/S0007087415000618. PMID 26337528.

- ^ "Why Muslims have only few Nobel Prizes". Hurriyet. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Dr Ahmed Zewail "There is nothing fundamental in Islam against science."". 15 March 2017.

- ^ a b Clayton, Philip; Nasr, Seyyed (2006). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science: Islam and Science. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Huff, Toby (2007). Science, Religion, and Society: Islam and Science. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- ^ a b Brooke, John; İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2011). Science and Religion Around the World: Modern Islam. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-19-532-820-2.

- ^ Yasir Qadhi on video clip linked to Twitter by Abdullah Sameer Yasir Qadhi (25 August 2020). "Abdullah Sameer". Event occurs at 12:56 PM. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Abdus Salam, Ideals and Realities: Selected Essays of Abdus Salam (Philadelphia: World Scientific, 1987), p. 109.

- ^ Nafiu Baba Ahmed, Secretary General of the Supreme Council for Sharia in Nigeria, telling the BBC his opinion of polio and vaccination. In northern Nigeria "more than 50% of the children have never been vaccinated against polio", and as of 2006 where more than half the world's polio victims live. Nigeria's struggle to beat polio, BBC News, 31 March 20

- ^ Mackey, The Iranians : Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation, 1996, p. 179.

- ^ Gamini, Amir Mohammad (23 August 2018). "Imamate Shiite Ulama and the Modern Astronomy in Qajar Period". Tarikh-e Elm. 16 (1): 65–93. doi:10.22059/jihs.2019.288941.371519. ISSN 1735-0573.

- ^ Brooke, John; İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2011). Science and Religion Around the World: Modern Islam. Oxford University press.

- ^ Kaya, Veysel. "Can the Quran support Darwin? an evolutionist approach by two Turkish scholars after the foundation of the Turkish Republic." The Muslim World 102.2 (2012): 357-370.

- ^ Kaya, Veysel. "Can the Quran support Darwin? an evolutionist approach by two Turkish scholars after the foundation of the Turkish Republic." The Muslim World 102.2 (2012): 357-370.

- ^ Kaya, Veysel. "Can the Quran support Darwin? an evolutionist approach by two Turkish scholars after the foundation of the Turkish Republic." The Muslim World 102.2 (2012): 357-370.

- ^ Kaya, Veysel. "Can the Quran support Darwin? an evolutionist approach by two Turkish scholars after the foundation of the Turkish Republic." The Muslim World 102.2 (2012): 357-370.

- ^ Kaya, Veysel. "Can the Quran support Darwin? an evolutionist approach by two Turkish scholars after the foundation of the Turkish Republic." The Muslim World 102.2 (2012): 357-370.

- ^ Erdağı, D. Evil in Turkish Muslim horror film: the demonic in “Semum”. SN Soc Sci 4, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-024-00832-w

- ^ Erdağı, D. Evil in Turkish Muslim horror film: the demonic in “Semum”. SN Soc Sci 4, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-024-00832-w

- ^ Erdağı, D. Evil in Turkish Muslim horror film: the demonic in “Semum”. SN Soc Sci 4, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-024-00832-w

- ^ Qutb, Muhammad (2000). Islam the Misunderstood Religion. Markazi Maktaba Islami. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Saudi cleric rejects that Earth revolves around the Sun".

- ^ "'War on Education': Taliban Converting Secular Schools into Religious Seminaries".

- ^ Qur'an and Science, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ^ a b Ali, Shamsher. "Science and the Qur'an" (PDF). In Oliver Leaman (ed.). The Qurʼan: An Encyclopedia. p. 572. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. p. 63. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. p. 75. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. pp. 132, 134. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Toshihiko Izutsu (1964). God and Man in the Koran. Weltansckauung. Tokyo.

- ^ A. I. Sabra, Situating Arabic Science: Locality versus Essence.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. p. 174. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. p. 56. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. pp. 117–18. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ Nidhal Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B.Tauris. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-1848855175.

- ^ a b Guessoum, Nidhal (June 2008). "The QUR'AN, SCIENCE, AND THE (RELATED) CONTEMPORARY MUSLIM DISCOURSE". Zygon. 43 (2): 413. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.2008.00925.x. ISSN 0591-2385. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b Qutb, Sayyid, Milestones, p. 112

- ^ Stark, Rodney, The Victory of Reason, Random House: 2005, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Edis, Taner (2007). An Illusion of Harmony: Science And Religion in Islam: Taner Edis: 9781591024491: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-1591024491.

- ^ a b c "Reasonable Doubts Podcast". CastRoller. 2014-07-11. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f SARDAR, ZIAUDDIN (21 August 2008). "Weird science". New Statesman. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Johanna Pink (2010). Sunnitischer Tafsīr in der modernen islamischen Welt: Akademische Traditionen, Popularisierung und nationalstaatliche Interessen. Brill, ISBN 978-9004185920, pp. 120–121

- ^ Cook, The Koran, 2000: p.29

- ^ a b Ansari, Zafar Ishaq (2001). "Scientific Exegesis of the Qur'an / التفسير العلمي للقرآن". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 3 (1): 92. doi:10.3366/jqs.2001.3.1.91. JSTOR 25728019.

- ^ "BLACK HOLES". miracles of the quran. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b Rizvi, Atheist Muslim, 2016: p.121

- ^ Saadat, Sabiha (January 2009). "Human Embryology and the Holy Quran: An Overview". International Journal of Health Sciences. 3 (1): 103–109. PMC 3068791. PMID 21475518.

- ^ Moore, Keith L. (1983). The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Emryology with Islamic Additions. Abul Qasim Publishing House (Saudi Arabia). Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Rizvi, Atheist Muslim, 2016: p.120-1

- ^ Joseph Needham, revised with the assistance of Arthur Hughes, A History of Embryology (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1959), p.82

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith L. "A Scientist's Interpretation of References to Embryology in the Qur'an". Islam 101. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Rizvi, Atheist Muslim, 2016: p.121-2

- ^ a b c Rizvi, Atheist Muslim, 2016: p.124

- ^ "THE SEQUENCE IN DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN ORGANS". Miracles of the Quran. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Rizvi, Atheist Muslim, 2016: p.122

- ^ von Staden, H. (May–Jun 1992). "The discovery of the body: human dissection and its cultural contexts in ancient Greece". Yale J Biol Med. 65 (3): 223–41. PMC 2589595. PMID 1285450.

- ^ "Surah As-Sajdah [32:9]". Surah As-Sajdah [32:9]. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ^ Golden, Daniel (23 January 2002). "Western Scholars Play Key Role In Touting 'Science' of the Quran". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Rohani Mashhadi, Farzaneh; Hasanzadeh, Gholamreza (2022). "An Evolutionary Reading of Adam's Creation in the Qur'an with Emphasis on the Concepts of Creation and Selection". Journal of Interdisciplinary Qur'anic Studies. 1 (1): 63–76. doi:10.37264/jiqs.v1i1.4.

- ^ Cook, The Koran, 2000: p.30

- ^ see also: Ruthven, Malise. 2002. A Fury For God. London: Granta. p. 126.

- ^ a b c "Beyond Bucailleism: Science, Scriptures and Faith". Evidence for God's Unchanging World. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Hoodbhoy, Pervez (2005). "When Science Teaching Becomes A Subversive Activity". In Koertge, Noretta (ed.). Scientific Values and Civic Virtues Get access Arrow. Oxford University Press. pp. 215–219. doi:10.1093/0195172256.003.0014. ISBN 0195172256.

- ^ "Scientific Miracles of the Quran, 19 – Roundness of the Earth". Windows of Islam. Event occurs at 0:55s. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Mathematical miracles of the Quran". Miracles of the Quran.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ TALIB, ALI (9 April 2018). "Deconstructing the "Scientific Miracles in the Quran" Argument". Transversing Tradition. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Scientific exegesis of the Qur'an--a viable project?".

- ^ "Religious perspectives on the science of Human Origins - Dr. Mustansir Mir, Ph.D" (PDF).

Further reading

[edit]- Huff, Toby. The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "Islam, Muslims, and modern technology." Islam and Science 3.2 (2005): 109–126. online

- Stearns, Justin. "The Legal Status of Science in the Muslim World in the Early Modern Period: An Initial Consideration of Fatwās from Three Maghribī Sources." in The Islamic Scholarly Tradition (Brill, 2011) pp. 265–290. online

External links

[edit]- Islam & Science

- Science and the Islamic world—The quest for rapprochement by Pervez Hoodbhoy.

- Islamic Science by Ziauddin Sardar (2002).

- Can Science Dispense With Religion? Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine by Mehdi Golshani.

- Islam, science and Muslims by Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

- Center for Islam and Science

- Explore Islamic achievements and contributions to science

- Is There Such A Thing As Islamic Science? The Influence Of Islam On The World Of Science

- How Islam Won, and Lost, the Lead in Science

- Radicalism among Muslim professionals worries many