Aniconism in Islam

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2011) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

In some forms of Islamic art, aniconism (the avoidance of images of sentient beings) stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry and in part from the belief that the creation of living forms is God's prerogative.

The Quran itself does not prohibit visual representation of any living being. The hadith collection of Sahih Bukhari explicitly prohibits the making of images of living beings, challenging painters to "breathe life" into their images and threatening them with punishment on the Day of Judgment.[1][2][a] Muslims have interpreted these prohibitions in different ways in different times and places. Religious Islamic art has been typically characterized by the absence of figures and extensive use of calligraphic, geometric and abstract floral patterns.

However, representations of Muhammad (in some cases, with his face concealed) and other religious figures are found in some manuscripts from lands to the east of Anatolia, such as Persia and India. Other forms of figurative arts existed since the formative stage of Islam.[4] These pictures were meant to illustrate the story and not to infringe on the Islamic prohibition of idolatry, but many Muslims regard such images as forbidden.[1] In secular art of the Muslim world, representations of human and animal forms historically flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures, although, partly because of opposing religious sentiments, figures in paintings were often stylized, giving rise to a variety of decorative figural designs. There were episodes of iconoclastic destruction of figurative art, such as the temporary decree by the Umayyad caliph Yazid II in 721 CE ordering the destruction of all representational images in his realm.[2][5] A number of historians have seen an Islamic influence on the Byzantine iconoclastic movement of the 8th century, though others regard this is as a legend that arose in later times in the Byzantine empire.[6]

Theological views

[edit]The Quran, the Islamic holy book, does not prohibit the depiction of human figures; it merely condemns idolatry.[7][8] Interdictions of figurative representation are present in the hadith, among a dozen of the hadith recorded during the latter part of the period when they were being written down. Because these hadith are tied to particular events in the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, they need to be interpreted in order to be applied in any general manner.

Sunni exegetes of tafsir, from the 9th century onward, increasingly saw in them categorical prohibitions against producing and using any representation of living beings. There are variations between religious maḏāhib (schools) and marked differences between different branches of Islam. Aniconism is common among fundamentalist Sunni sects such as Salafis and Wahhabis (which are also often iconoclastic), and less prevalent among liberal movements within Islam. Shia and mystical orders also have less stringent views on aniconism. On the individual level, whether or not specific Muslims believe in aniconism will depend on how hadiths related to the topic are interpreted.

Aniconism in Islam not only deals with the material image, but touches upon mental representations as well. It is a problematic issue, discussed by early theologians, as to how to describe God, Muhammad and other prophets, and, indeed, if it is permissible at all to do so. God is usually represented by immaterial attributes, such as "holy" or "merciful", commonly known from his "Ninety-nine beautiful names". Muhammad's physical appearance, however, is amply described, particularly in the traditions on his life and deeds recorded in the biographies known as Sirah Rasul Allah. Of no less interest is the validity of sightings of holy personages made during dreams.

Titus Burckhardt sums up the role of aniconism in Islamic aesthetics as follows:

The absence of icons in Islam has not merely a negative but a positive role. By excluding all anthropomorphic images, at least within the religious realm, Islamic art aids man to be entirely himself. Instead of projecting his soul outside himself, he can remain in his ontological centre where he is both the viceregent (khalîfa) and slave ('abd) of God. Islamic art as a whole aims at creating an ambience which helps man to realize his primordial dignity; it therefore avoids everything that could be an 'idol', even in a relative and provisional manner. Nothing must stand between man and the invisible presence of God. Thus Islamic art creates a void; it eliminates in fact all the turmoil and passionate suggestions of the world, and in their stead creates an order that expresses equilibrium, serenity and peace.[9]

In practice

[edit]

Religious core

[edit]In practice, the core of normative religion in Islam is consistently aniconic. Spaces such as the mosque and objects like the Quran are devoid of figurative images. Other spheres of religion, for example mysticism, popular piety, or private devotion exhibit significant variability in this regard. Aniconism in secular contexts is even more variable and there are many examples of figural representation in secular art throughout history. Generally speaking, aniconism in Islamic societies is restricted in modern times to specific religious contexts. In the past, it was enforced only in some times and places.[10]

Past

[edit]The representation of living beings in Islamic art is not just a modern phenomenon and examples are found from the earliest periods of Islamic history. Frescos and reliefs of humans and animals adorned palaces of the Umayyad era, as on the famous Mshatta Facade now in Berlin.[11][12] The ‘Abbasid Palaces at Samarra also contained figurative imagery. Ceramics, metalware, and objects in ivory, rock crystal, and other media also bore figural imagery in the medieval era.[13] Figurative miniatures in books occur later in most Islamic countries but somewhat less in Arabic-speaking areas. The human figure is central to the Persian miniature and other traditions such as the Ottoman miniature and Mughal painting.[14][15] The Persian miniature tradition began when Persian courts were dominated by Sunnis, but continued after the Shia Safavid dynasty took power. The Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp I of Persia began his reign as a keen patron and amateur artist himself, but turned against painting and other forbidden activities after a religious midlife crisis.[16]

The avoidance of idolatry is the main concern of the restrictions on images, and as a result, the traditional form for the religious cult image, the free-standing sculpture, is extremely rare, though examples of freestanding human sculpture do occur in Umayyad Syria and in Seljuk Iran.[17] The Pisa Griffin, of a mythical beast and designed to spout water for a fountain, is the largest example, at three feet tall in bronze, and probably only survives because it was taken as booty by the city of Pisa in the Middle Ages.[18] Like the famous lions supporting a fountain in the Alhambra, it probably came from Al-Andalus. The griffin and lions cannot easily be regarded as potential idols, given their submissive position (and the lack of religions worshipping lions or griffins), and the same is true of small decorative figures in relief on objects in metalwork, or figures painted on Islamic pottery, both of which are relatively common.[19] In particular hunting scenes of humans and animals were popular, and presumably regarded as clearly having no religious function. The figures in miniatures were, until the late 16th century, always numerous in each image, small (typically only an inch or two high), and showing the central figures at roughly the same size as the attendants and servants who are usually also shown, thus deflecting potential accusations of idolatry. The books illustrated were most often the classics of Persian poetry and historical chronicles.

The hadith show some concessions for context, as with the dolls, and condemn most strongly the makers rather than the owners of images.[20] A long tradition of prefaces to muraqqas sought to justify the creation of images without getting involved in discussions of the specific texts, using arguments such as comparing God to an artist.[21]

Miniature painting was mostly patronized by the court circle and is a private form of art; the owner chooses whom to show a book or muraqqa (album). But wall-paintings with large figures were found in early Islam, and in Safavid and later Persia, especially from the 17th century, but were always rare in the Arabic-speaking world. Such paintings are also mainly found in private palaces; examples in public buildings are rare though not unknown, in Iran there are even some in mosques.

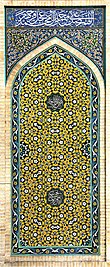

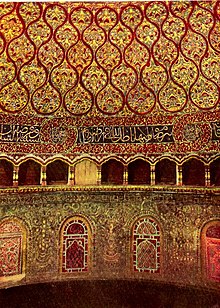

Eschewing figural representation, ornamentation in Islamic sacred architecture relies chiefly on arabesque and geometrical patterns.

Early examples of non-figural representation in Islamic sacred architecture are found in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus and the Dome of the Rock. The murals of the Dome of the Rock use crowns and jewels to symbolize earthly rulership and "otherworldly" plants as an invocation of the Quranic description of heaven.[22] Similarly, the murals in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, which depict an idyllic cityscape are also meant to be an evocation of paradise without figural representation.[22]

The issue of aniconism has posed problems in the modern world, especially as technologies like television developed in the 20th century. For many years, Wahhabi clerics opposed the establishment of a television service in Saudi Arabia, as they believed it immoral to produce images of humans.[23] The introduction of television in 1965 offended some Saudis, and one of King Faisal's nephews, Prince Khalid ibn Musa'id ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz,[24] was killed in a police shootout in August 1965 after he led an assault on one of the new television stations.[25]

Present

[edit]Depending on which segment of Islamic societies are referred to, the application of aniconism is characterized by noteworthy differences.[26] Factors are the epoch considered, the country, the religious orientation, the political intent, the popular beliefs, the private benefit or the dichotomy between reality and discourse.

Today, the concept of an aniconic Islam coexists with a daily life for Muslims awash with images. TV stations and newspapers (which do present still and moving representations of living beings) have an exceptional impact on public opinion, sometimes, as in the case of Al Jazeera, with a global reach, beyond the Arabic speaking and Muslim audience. Portraits of secular and religious leaders are omnipresent on banknotes[27][28] and coins, in streets and offices (e.g. presidents like Nasser and Mubarak, Arafat, al-Assad, kings like House of Saud or Hezbollah's Nasrallah and Ayatollah Khomeini). Anthropomorphic statues in public places are to be found in most Muslim countries (Saddam Hussein's are infamous[29]), as well as art schools training sculptors and painters. In the Egyptian countryside, it is fashionable to celebrate and advertise the returning of pilgrims from Mecca on the walls of their houses.

The Taliban movement in Afghanistan banned photography and destroyed non-Muslim artifacts, especially carvings and statues such as the Buddhas of Bamiyan, generally tolerated by other Muslims, on the grounds that the artifacts are idolatrous or shirk. However, sometimes those who profess aniconism will practice figurative representation (cf. portraits of Talibans from the Kandahar photographic studios during their imposed ban on photography[30]).

For Shia communities, portraits of the major figures of Shiite history are important elements of religious devotion. In Iran, portraits of Muhammad and of Ali, printed on pieces of cloth or woven into carpets, are called temsal ("likenesses") and can be bought around shrines and in the streets, to be hung in homes or carried with oneself.[31] In Pakistan, India and Bangladesh portraits of Ali can be found on notoriously ornate trucks,[32] buses and rickshaws.[33] Contrary to the Sunni tradition, a photographic picture of the deceased can be placed on the Shiite tombs.[34][35] A curiosity in Iran is an Orientalist photography supposed to represent Muhammad as a young boy.[36] The Grand Ayatollah Sistani of Najaf in Iraq has given a fatwā declaring the depiction of Muhammad, the prophets and other holy characters, permissible if it is made with the utmost respect.[37]

Circumvention methods

[edit]Medieval Muslim artists found various ways to represent especially sensitive figures such as Muhammad. He is sometimes shown with a fiery halo hiding his face, head, or whole body, and from about 1500 is often shown with a veiled face.[38] Members of his immediate family and other prophets may be treated in the same way. At the material level, prophets in manuscripts can have their face covered by a veil or all humans have a stroke drawn over their neck, symbolizing the severing of the soul, and clarifying the fact that it is not something alive and imbued with a soul that is depicted: a purposeful flaw to make what is depicted impossible to live in reality (as merely impossible in reality is still often frowned upon or banned, such as representations of comic book characters or unicorns, although exceptions do exist). Few portraits were attempted, and the ability to create recognizable portraits was rare in Islamic art until the Mughal tradition began in the late 15th century, although in both Mughal India and Ottoman Turkey portraits of the ruler then became very popular in court circles.[39]

Islamic calligraphy has also displayed figurative themes. Examples of this are anthropomorphic and zoomorphic calligrams.[40] Islamic calligraphy forms evolved, especially in the Ottoman period, to fulfill a function similar to figurative art.[41] When on paper, Islamic calligraphy is often seen with elaborate frames of Ottoman illumination.[41] Examples of Islamic calligraphy using this technique include the name of Muhammad, the Hilya (a tablet that embodies the description of Muhammad’s physical appearance), multiple names of God in Islam, and the tughra (a calligraphic version of the name of an Ottoman sultan).[42][43]

Scriptural basis

[edit]Hadith and exegesis examples

[edit]All hadith presented in this section are Sunni, not Shia.

Pro-art

[edit]Narrated Aisha:

Upon the Prophet’s arrival from a military expedition, a curtain covering Aisha’s store-room was raised by the blowing wind, uncovering her dolls. Among them, the Prophet saw a horse with two wings made of rags and asked his wife what was on the horse. Aisha responded that it was two wings. He asked: A horse with two wings? Aisha then asked if the Prophet had not heard that Solomon had horses with wings. The Hadith reports that the Prophet laughed heartily where his molar teeth were seen.— Abu Dawood, Sunan Abu Dawood[44],

Reference (English Book) Book 42, Hadith 4914

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 43, Hadith 160

Narrated Busr bin Sa`id:

That Zaid bin Khalid Al-Juhani narrated to him something in the presence of Sa`id bin 'Ubaidullah Al- Khaulani who was brought up in the house of Maimuna the wife of the Prophet. Zaid narrated to them that Abu Talha said that the Prophet (ﷺ) said, "The Angels (of Mercy) do not enter a house wherein there is a picture." Busr said, "Later on Zaid bin Khalid fell ill and we called on him. To our surprise we saw a curtain decorated with pictures in his house. I said to Ubaidullah Al-Khaulani, "Didn't he (i.e. Zaid) tell us about the (prohibition of) pictures?" He said, "But he excepted the embroidery on garments. Didn't you hear him?" I said, "No." He said, "Yes, he did."— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[45]

Middle ground between pro- and anti-

[edit]A'isha reported: The Prophet’s wife describes owning a curtain with bird portraits. The Prophet asked for the curtain to be changed, for when he entered the room it brought to him pleasures of worldly life. Aisha describes also having worn sheets with silk badges, which the Prophet did not command to be torn.

— Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Sahih Muslim[46],

Reference (English Book) Book 24, Hadith 5255

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 38, Hadith 5643

Narrated Ali ibn Abu Talib:

Safinah AbuAbdurRahman, Ali ibn Abu Talib, and Fatimah invited the Prophet to eat with them. Upon the Prophet’s arrival, he turned away after seeing figural curtains hanging at the end of the house. Ali followed the Prophet to ask what had turned him back. The Prophet stated that it is unfitting for him or any Prophet to enter a home decorated [with figural imagery].— Abu Dawood, Sunan Abu Dawood[47],

Reference (English Book) Book 27, Hadith 3746

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 28, Hadith 20

To show the superiority of the monotheist faith, Muhammad smashed the idols at the Kaaba. He also removed paintings that were blasphemous to Islam, while protecting others (the images of Mary and Jesus) inside the building.[48] The hadith below emphasizes that aniconism depends not only on what, but also on how things are depicted.

Narrated Ibn Abbas:

The Prophet refused to enter the Kaaba with idols in it and ordered they be removed. Pictures of Abraham and Ishmael holding arrows of divination were carried out and the Prophet stated, “May Allah ruin the infidels for the false portrayal of the acts of Abraham and Ishmael. The Hadith reports that the Prophet said "Allahu Akbar" inside all directions of the Kaaba and left without prayer therein.— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[49],

Reference (English Book) Vol. 5, Book 59, Hadith 584

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 64, Hadith 4333

Narrated 'Aisha:

When the Prophet became ill, amongst his wives there was talk of a church in Ethiopia with descriptions of its beauty and pictures it contained. The Hadith reports the Prophet saying the creators are the worst creatures in the sight of Allah for they are the people who, upon the death of a pious man amongst them, make a place of worship at his grave and create pictures in it.— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[50],

Reference (English Book) Vol. 2, Book 23, Hadith 425

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 23, Hadith 425

Anti-art

[edit]Narrated Aisha:

The wife of the Prophet purchased a cushion with pictures of animals on it for the Prophet to sit on and recline on. The Prophet disapproved of the making of such pictures, saying the makers would be punished on the Day of Resurrection when God would ask them to bring their creations to life. The Hadith also reports that the Prophet said that the angels would not enter a house where there are pictures.— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[51],

Reference (English Book) Vol. 7, Book 62, Hadith 110

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 67, Hadith 5181

Narrated 'Aisha:

Upon the arrival of the Prophet from a journey, he saw and tore a curtain with pictures his wife had placed over the door of a chamber. The Prophet disapproved of the making of such pictures, saying those who try to make the like of Allah's creations will receive the severest punishment on the Day of Resurrection.— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[52],

Reference (English Book) Vol. 7, Book 72, Hadith 838

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 77, Hadith 6019

Aisha describes the Prophet tearing a curtain with portraits on it as soon as he saw it. The Hadith reports that the Prophet said the most grievous torment from the Hand of Allah on the Day of Resurrection would be for those who imitate (Allah) in the act of His creation. The torn pieces were made into cushions.

— Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Sahih Muslim[53],

Reference (English Book) Book 24, Hadith 5261

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 38, Hadith 5650

Narrated Salim's father:

Upon Gabriel’s delay to visit the Prophet, he stated that they do not enter a place in which there is a picture or a dog— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari[54],

Reference (English Book) Vol. 7, Book 72, Hadith 843

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 77, Hadith 6026

Muslim b. Subaih reported being in a house with Masriuq which had portrayals of Mary. Masriuq had heard Abdullah b, Mas'ud stating that the Prophet had said the most grievously tormented people on the Day of Resurrection would be the painters of pictures. After this message was read before Nasr b. 'Ali al-Jahdhami and other narrators, the last one being Ibn Sa'id b Abl at Hasan, one person asked for a religious verdict for one like himself who paints pictures. Ibn 'Abbas narrated to the person the Prophet’s sayings in which painters who make pictures would be punished in the fire of Hell and the soul will be breathed in every picture prepared by him. Only pictures of paintings of trees and lifeless things should be allowed.

— Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Sahih Muslim[55],

Reference (English Book) Book 24, Hadith 5272

Reference (Arabic Book) Book 38, Hadith 5661

See also

[edit]- Aniconism in Christianity

- Aniconism in Judaism

- Arabic miniature

- Censorship by religion

- Censorship in Islamic societies

- Depictions of Muhammad

- Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL

- Destruction of early Islamic heritage sites in Saudi Arabia

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- Image veneration in Shia Islam

- Taghut

Notes

[edit]- ^ This hadith may have reflected an aniconistic atmosphere at the time in the Middle East: a few decades prior to its publication, Christian authorities of Byzant opposed depictions of figurative arts, as statues and images were believed to be inhabited by devils. This sentiment might have been adapted by Muslim authors at that time, explaining the different attitudes towards images throughout Islamic history.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Esposito, John L. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b "Figural Representation in Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Brend, Barbara. "Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzād of Herāt (1465–1535). By Michael Barry. p. 231-233. Paris, Flammarion, 2004." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 17.1 (2007): 231-233.

- ^ Brend, Barbara. "Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzād of Herāt (1465–1535). By Michael Barry. p. 49. Paris, Flammarion, 2004." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 17.1 (2007): 49

- ^ Wolfram Drews (2011). "Jewish or Islamic Influence? The Iconoclastic Controversy Dispute". Cultural Transfers in Dispute. Representations in Asia, Europe and the Arab World since the Middle Ages. Germany: Campus Verlag. p. 42.

- ^ Wolfram Drews (2011). "Jewish or Islamic Influence? The Iconoclastic Controversy Dispute". Cultural Transfers in Dispute. Representations in Asia, Europe and the Arab World since the Middle Ages. Germany: Campus Verlag. pp. 55–60.

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780199794133.

- ^ Quran 5:87–92, 21:51–52

- ^ Titus Burckhardt (1 October 1987). Mirror of the intellect: essays on traditional science & sacred art. SUNY Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-88706-684-9. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ Gruber, Christiane J., 1976-. The Praiseworthy One : the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic texts and images. Bloomington, Indiana, USA. ISBN 978-0-253-02526-5. OCLC 1083783078.

- ^ Allen, Terry, "Aniconism and Figural Representation in Islamic Art", Palm Tree Books Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Educational Site: Archaeological Sites: Qusayr `Amra Archived August 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hoffman, Eva R. (2008-03-22). "Between East and West: The Wall Paintings of Samarra and the Construction of Abbasid Princely Culture". Muqarnas Online. 25 (1): 107–132. doi:10.1163/22118993_02501005. ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ Reza Abbasi Museum Archived September 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Portraits of the Sultans," Topkapi Palace Museum Archived November 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dickson, Martin (1958). Sháh Tahmásb and the Úzbeks (the duel for Khurásán with ʻUbayd Khán; 930-946/1524-1540). Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University. p. 190.

- ^ Canby, Sheila R, Deniz Beyazit, Martina Rugiadi, A. C. S Peacock, and N.Y.) Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York. Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, 2016, p. 40-47

- ^ Mack, p. 3 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Canby, Sheila R, Deniz Beyazit, Martina Rugiadi, A. C. S Peacock, and N.Y.) Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York. Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, 2016, p. 121

- ^ The image debate : figural representation in Islam and across the world. Gruber, Christiane J., 1976-. London. ISBN 978-1-909942-34-9. OCLC 1061820255.

- ^ Roxburgh, David J. Prefacing the Image: The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran. Studies and Sources in Islamic Art and Architecture, v. 9. Leiden ; Brill, 2001.

- ^ a b George, Alain. Paradise or Empire?: On a Paradox of Umayyad Art. Power, Patronage, and Memory in Early Islam (2018). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Boyd, Douglas A. (Winter 1970–71). "Saudi Arabian Television". Journal of Broadcasting. 15 (1).

- ^ R. Hrair Dekmejian (1995). Islam in Revolution: Fundamentalism in the Arab World. Syracuse University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8156-2635-0. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Saudi Time Bomb?". Frontline PBS.

- ^ See 'Sura' and 'Taswir' in Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ Petroleum-related banknotes: Saudi Arabia: Oil Refinery Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Petroleum-related banknotes: Iran: Abadan Refinery, Iahanshahi-Amouzegar Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "U.S. military, not Iraqis, behind toppling of statue | The Honolulu Advertiser | Hawaii's Newspaper". the.honoluluadvertiser.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Jon Lee Anderson, Thomas Dworzak, Taliban, London (UK), Trolley, 2003, ISBN 0-9542648-5-1.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2011). Shi'ism - A Religion of Protest. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : Masterpieces to Go: The Trucks of Pakistan". archive.aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Rickshaw Arts of Bangladesh". Archived from the original on October 21, 2009.

- ^ "Picture of Golestan e Shohoda cemetery Esfahan -Esfahan, Iran". Archived from the original on October 18, 2012.

- ^ "Mashad Martyrs Cemetery at Best Iran Travel.com". Archived from the original on April 7, 2015.

- ^ Photography by Lehnert & Landrock, titled "Mohamed", Tunis, c. 1906. Nicole Canet, Lehnert & Landrock. Photographies orientatlistes 1905-1930. (Paris: Galerie Au Bonheur du Jour, 2004): cover, p. 9. dead link Archived May 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine . Historical context described in (in French) Patricia Briel, letemps.ch, 22 February 2006. Ces étranges portraits de Mahomet jeune[dead link]

- ^ Grand Ayatollah Uzma Sistani, Fiqh & Beliefs: Istifa answers, personal website. (accessed 17 February 2006) (in Arabic)[permanent dead link], "WWW.SISTANI.ORG : الصفحة الرئيسية". Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ^ Gruber, Christiane (2009). "Between Logos (Kalima) And Light (Nūr): Representations Of The Prophet Muhammad In Islamic Painting". Muqarnas. Vol. 26. Brill. pp. 229–262. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004175891.i-386.66. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1. JSTOR 27811142. S2CID 194020568.

- ^ Fetvacı, Emine. Picturing History at the Ottoman Court / Emine Fetvacı. Indiana University Press, 2014. p.254

- ^ Robinson, Francis (1992). "Review of Calligraphy and Islamic Culture". Journal of Islamic Studies. 3 (1): 100–103. doi:10.1093/jis/3.1.100. JSTOR 26196535.

- ^ a b FETVACI, EMINE (2012). "The Album of Ahmed I". Ars Orientalis. 42: 127–138. JSTOR 43489770.

- ^ "Hilya (Votive Tablet)". The Met.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (1989). "An Exhibition of High Ottoman Art". Muqarnas. 6: 1–11. doi:10.2307/1602275. JSTOR 1602275.

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawood, 41:4914

- ^ [Sahih al Bukhari, 3226 https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3226]

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 24:5255

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawood, 27:3746

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1955). The Life of Muhammad. A translation of Ishaq's "Sirat Rasul Allah". Oxford University Press. p. 552. ISBN 978-0-19-636033-1. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:59:584

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:23:425

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 3:34:318, 7:62:110

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:72:838

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 24:5261

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:72:843

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 24:5272

General

[edit]- Jack Goody, Representations and Contradictions: Ambivalence Towards Images, Theatre, Fiction, Relics and Sexuality, London, Blackwell Publishers, 1997. ISBN 0-631-20526-8.

Islam

[edit]- Oleg Grabar, "Postscriptum", The Formation of Islamic Art, Yale University, 1987 (p209). ISBN 0-300-03969-7

- Terry Allen, "Aniconism and Figural Representation in Islamic Art", Five Essays on Islamic Art, Occidental (CA), Solipsist, 1988. ISBN 0-944940-00-5 Aniconism and Figural Representation in Islamic Art, by Terry Allen

- Gilbert Beaugé & Jean-François Clément, L'image dans le monde arabe [The image in the Arab world], Paris, CNRS Éditions, 1995, ISBN 2-271-05305-6 (in French)

- Rudi Paret, Das islamische Bilderverbot und die Schia [The Islamic prohibition of images and the Shi'a], Erwin Gräf (ed.), Festschrift Werner Caskel, Leiden, 1968, 224-32. (in German)