Islam in Malta

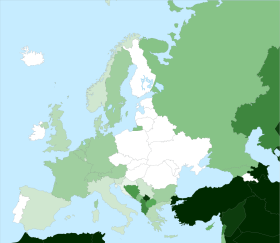

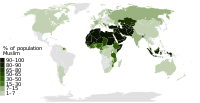

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam in Malta (Arabic: الإسلام في مالطا) has had a historically profound influence upon the country—especially its language and agriculture—as a consequence of several centuries of control and presence on the islands. Today, the main Muslim organization represented in Malta is the Libyan World Islamic Call Society.[2]

The 2021 census found that the Muslim population in Malta grew from 6,000 in 2010 to 17,454 in 2021, mainly non-citizens, totalling 3.9% of the population.[3] Of these a small amount, 1,746, are Maltese citizens.

History

[edit]Prior to Muslim rule, Eastern Christianity had been prominent in Malta during the time of Greek-Byzantine rule.[4][5] The thesis of a Christian continuity in Malta during Arab rule, despite being popular, is historically unfounded.[6]

Aghlabid period: 870–1091

[edit]

Islam is believed to have been introduced to Malta when the North African Aghlabids, first led by Halaf al-Hadim and later by Sawada ibn Muhammad,[7] conquered the islands from the Byzantines, after arriving from Sicily in 870[8] (as part of the wider Arab–Byzantine wars).[9] However, it has also been argued that the islands were occupied by Muslims earlier in the 9th, and possibly 8th, century.[10] The Aghlabids established their capital in Mdina.[11] The old Roman fortification, later to become Fort St Angelo, was also extended.[12]

According to the Arab chronicler and geographer al-Ḥimyarī (author of Kitab al-Rawḍ al-Miṭar), following the Muslim attack and conquest, Malta was practically uninhabited until it was colonised by Muslims from Sicily in 1048–1049, or possibly several decades earlier.[7] As recognised by the acclaimed Maltese historian Godfrey Wettinger, the Arab conquest broke any continuity with previous population of the island. This is also consistent with Joseph Brincat’s linguistic finding of no further sub-stratas beyond Arabic in the Maltese language, a very rare occurrence which may only be explained by a drastic lapse between one period and the following.[6]

The strongest legacy of Islam in Malta is the Maltese language,[13] which is very close to Tunisian arabic. and most place names (other than the names Malta and Gozo[14]) are Arabic, as are most surnames, e.g. Borg, Cassar, Chetcuti, Farrugia, Fenech, Micallef, Mifsud and Zammit.[15][16][17] It has been argued that this survival of the Maltese language, as opposed to the extinction of Siculo-Arabic in Sicily, is probably due to the eventual large-scale conversions to Christianity of the proportionally large Maltese Muslim population.[18]

The Muslims also introduced innovative and skillful irrigation techniques such as the water-wheel known as the Noria or Sienja,[19] all of which made Malta more fertile.[20] They also introduced sweet pastries and spices and new crops, including citrus, figs, almond,[12] as well as the cultivation of the cotton plant, which would become the mainstay of the Maltese economy for several centuries,[21] until the latter stages of the rule of the Knights of St. John.[19] The distinctive landscape of terraced fields is also the result of introduced ancient Arab methods.[12] Maltese Catholicism remained influenced by the Muslim presence and background,[22] including for the words for God (Alla) and Lent (Randan).

Elements of Islamic architecture also remain in the vernacular Maltese style, including the muxrabija, wooden oriel windows similar to the mashrabiya.

Norman period: 1091–1224

[edit]

Malta returned to Christian rule with the Norman conquest in 1127.[6] It was, with Noto on the southern tip of Sicily, the last Arab stronghold in the region to be retaken by the resurgent Christians.[23]

The Arab administration was initially kept in place[24] and Muslims were allowed to practise their religion freely until the 13th century.[25] The Normans allowed an emir to remain in power with the understanding that he would pay an annual tribute to them in mules, horses, and munitions.[26] As a result of this favourable environment, Muslims continued to demographically and economically dominate Malta for at least another 150 years after the Christian conquest.[27]

In 1122 Malta experienced a Muslim uprising and in 1127 Roger II of Sicily reconquered the islands.[28]

Even in 1175, Burchard, bishop of Strasbourg, an envoy of Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, had the impression, based upon his brief visit to Malta, that it was exclusively or mainly inhabited by Muslims.[29]

In 1224, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, sent an expedition against Malta to establish royal control and prevent its Muslim population from helping a Muslim rebellion in the Kingdom of Sicily.[30]

The conquest of the Normans lead to the gradual Latinization and subsequent firm establishment of Roman Catholicism in Malta, after previous respective Eastern Orthodox and Islamic domination.[4][5]

Anjou and Aragonese period: 1225–1529

[edit]According to a report in 1240 or 1241 by Gililberto Abbate, who was the royal governor of Frederick II of Sicily during the Genoese Period of the County of Malta,[31] in that year the islands of Malta and Gozo had 836 Muslim families, 1250 Christian families and 33 Jewish families.[32]

In 1266, Malta was turned over in fiefdom to Charles of Anjou, brother of France’s King Louis IX, who retained it in ownership until 1283. Eventually, during Charles's rule religious coexistence became precarious in Malta, since he had a genuine intolerance of religions other than Roman Catholicism.[33] However, Malta's links with Africa would remain strong until the beginning of Spanish rule in 1283.[34]

According to the author Stefan Goodwin, by the end of the 15th century all Maltese Muslims would be forced to convert to Christianity and had to find ways to disguise their previous identities.[35] Professor Godfrey Wettinger, who specialized in Malta's medieval history, writes that the medieval Arab historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) puts the expulsion of Islam from Malta to the year 1249. Wettinger goes on to say that "there is no doubt that by the beginning of Angevin times [i.e. shortly after 1249] no professed Muslim Maltese remained either as free persons or even as serfs on the island."[36]

Knights of St. John: 1530–1798

[edit]

During the period of rule under the Knights Hospitaller, thousands of Muslim slaves, captured as a result of maritime raids,[31] were taken to Malta.[37] In the mid-18th century, there were around 9,000 Muslim slaves in Hospitaller-ruled Malta.[38] They were given a substantial amount of freedom, being allowed to gather for prayers.[39] Although there were laws preventing them from interacting with the Maltese people, these were not regularly enforced. Some slaves also worked as merchants, and at times were allowed to sell their wares in the streets and squares of Valletta.[40] A mosque was built in 1702 during the Order of St John[41] for Turkish slaves[42] within the Slaves' Prison[43] of which neither ruins nor description of its architecture now remain.

After the failure of the Conspiracy of the Slaves (1749), laws restricting the movement of slaves were made stricter. They could not go outside the city limits, and were not to approach any fortifications. They were not allowed to gather anywhere except from their mosque, and were to sleep only in the slave prisons. Moreover, they could not carry any weapons or keys of government buildings.[44]

There was also a deliberate and ultimately successful campaign, using disinformation and often led by the Roman Catholic clergy, to de-emphasize Malta's historic links with Africa and Islam.[45] This distorted history "determined the course of Maltese historiography till the second half of the twentieth century",[46] and it created the rampant Islamophobia which has been a traditional feature of Malta, like other southern European states.[47]

A number of Muslim cemeteries have been located in various locations around Marsa since the 16th century.[citation needed] A cemetery in il-Menqa contained the graves of Ottoman soldiers killed in the Great Siege of Malta of 1565 as well as Muslim slaves who died in Malta.[48][49] This cemetery was replaced in 1675 by another one near Spencer Hill (Via della Croce),[50] following the construction of the Floriana Lines.[51] Human remains believed to originate from one of these cemeteries were discovered during road works in 2012.[51][52] The remains of a cemetery, together with the foundations of a mosque, and an even more earlier Roman period remains are located at Triq Dicembru 13, Marsa.[53]

British period: 1800-1964

[edit]The 17th-century cemetery at Spencer Hill had to be relocated in 1865 to make way for planned road works,[54] with one tombstone dating to 1817 being conserved at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.[55]

A new cemetery was commissioned by the Ottoman sultan Abdülaziz, and it was constructed between 1873 and 1874[56] at Ta' Sammat in Marsa, as decided in 1871.[54] Construction took over six months to complete.[57] It was designed by the Maltese architect Emanuele Luigi Galizia[58][59] in Moorish Revival architecture. The design for the project was unique in Maltese architecture at that point.[60] Galizia was awarded the Order of the Medjidie by the Ottoman sultan for designing the Turkish cemetery,[54] and thus was made a Knight of that order.[61]

At the end of the 19th century the cemetery became a landmark by its own due to its picturesque architecture.[62] Due to the absence of a mosque at the time, the cemetery was generally used for Friday prayers until the construction of a mosque in Paola.[63] The small mosque at the cemetery was intended to be used for prayers during an occasional burial ceremony,[64] but the building and the courtyard of the cemetery became frequently used as the only public prayer site for Muslims until the early 1970s.[63]

A properly sized mosque was designed by Galizia but the project was abandoned. The plans are available in Turkish archives in Istanbul which hold the words “Progetto di una moschea – Cimitero Musulmano“ (Project for a mosque – Muslim Cemetery). A possible reason for shelving the project was the economic situation and political decline of the Ottoman Empire.[65] The place became too small eventually for the growing Muslim community.[66]

Independent Malta

[edit]

In modern times, Malta's unique culture has enabled it to serve as Europe's "bridge" to the Arab cultures and economies of North Africa.[67][further explanation needed]

After independence from the United Kingdom in 1964, Libya became an important ally of socialist Maltese leader Dom Mintoff. History books were published that began to spread the idea of a disconnection between the Italian and Catholic populations, and instead tried to promote the theory of closer cultural and ethnic ties with North Africa. This new development was noted by Boissevain in 1991:

...the Labour government broke off relations with NATO and sought links with the Arab world. After 900 years of being linked to Europe, Malta began to look southward. Muslims, still remembered in folklore for savage pirate attacks, were redefined as blood brothers.[68]

Malta and Libya also entered into a Friendship and Cooperation Treaty, in response to repeated overtures by Gaddafi for a closer, more formal union between the two countries; and, for a brief period, Arabic had become a compulsory subject in Maltese secondary schools.[69][70]

The Islamic Centre of Paola,[71] was founded in 1978 by the World Islamic Call Society, together with a Muslim school called the Maryam al-Batool school.[13] In 1984 the Mariam Al-Batool Mosque was officially opened by Muammar Gaddafi in Malta, two years after its completion.

Mario Farrugia Borg, later part of the personal office of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat,[72] was the first Maltese public officer to take an oath on the Koran when co-opted into the Qormi local council in 1998.[73]

In 2003, of the estimated 3,000 Muslims in Malta, approximately 2,250 were foreigners, approximately 600 were naturalised citizens, and approximately 150 were native-born Maltese.[74][needs update]

In 2008, a second translation of Qur’an into Maltese by professor Martin Zammit was published. By 2010, there were approximately 6,000 Muslims in Malta—most of whom are Sunni and foreigners.[75][a]

The 2021 Census in Malta found that the Muslim population grew from 6,000 in 2010 to 17,454 in 2021, mainly foreigners, totalling 3.9% of the population.[76] Of these, a small amount, 1,746, are Maltese citizens.

See also

[edit]- History of Malta

- History of Islam in southern Italy

- Siege of Malta (1429)

- Invasion of Gozo (1551)

- Great Siege of Malta

- Maymūnah Stone

- Turkish Military Cemetery

- Religion in Malta

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Muslim Population Growth in Europe Pew Research Center". 2024-07-10. Archived from the original on 2024-07-10.

- ^ Jørgen S. Nielsen; Samim Akgönül; Ahmet Alibasi; Egdunas Racius (12 October 2012). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Vol. 4. BRILL. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-90-04-22521-3.

- ^ "Census 2021: Maltese citizens overwhelmingly identify as Roman Catholics". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ a b Kenneth M. Setton, "The Byzantine Background to the Italian Renaissance" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 100:1 (Feb. 24, 1956), pp. 1–76.

- ^ a b Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʻı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37019-1.

- ^ a b c Godfrey Wettinger,Malta in the High Middle Ages, Speech at the Ambassadors’ Hall, Auberge de Castille, on 7 December 2010

- ^ a b Travel Malta. The Arab period and the Middle Ages: MobileReference. ISBN 978-1-61198-279-4.

- ^ Christian W. Troll; C.T.R. Hewer (12 Sep 2012). "Journeying toward God". Christian Lives Given to the Study of Islam. Fordham Univ Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8232-4319-8.

- ^ David W. Tschanz (October 2011). "Malta and the Arabs". p. 4. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Martijn Theodoor Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 (reprint (volume 5) ed.). BRILL. p. 213. ISBN 9789004097919.

- ^ Simon Gaul (2007). Malta, Gozo and Comino (illustrated ed.). New Holland Publishers. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-86011-365-9.

- ^ a b c "Arab Legacy – Arab Rule in Malta". Malta Tourism Authority. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ a b Christian W. Troll; C.T.R. Hewer (12 Sep 2012). "Journeying toward God". Christian Lives Given to the Study of Islam. Fordham Univ Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-8232-4319-8.

- ^ Neil Wilson; Carolyn Joy Bain (2010). "History". Malta and Gozo (illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 18. ISBN 9781741045086.

Apart from the names Malta and Gozo, which probably have Latin roots, there is not a single place name in the Maltese Islands that can be proved to predate the Arab occupation.

- ^ Aquilina, J. (1964). "A Comparative Study in Lexical Material relating to Nicknames and Surnames" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 2. Melita Historica: 154–158.

- ^ Kristina Chetcuti (9 February 2014). "Why most Maltese share the same 100 surnames". Times of Malta. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Juliet Rix (1 Apr 2013). "1 (History)". Malta (2, illustrated ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 9. ISBN 9781841624525.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 31. ISBN 9780897898201.

The likelihood that many Muslims in Malta eventually converted to Christianity rather than leave seems indicated by parallels in Sicily as well as by the fact that there is linguistic evidence suggesting that "there was a time when the church of Malta was fed by Christian Arabs." Luttrell [Anthony T. Luttrell] is also on record with the argument that "the persistence of the spoken Arabo-Berber language" in Malta can probably best be explained by eventual large-scale conversions of Maltese Muslims to Christianity. Even when Islam had completely been erased from the Maltese landscape, Arabic remained, especially as represented by colloquial dialects of the language spoken in Libya, Tunisia, and in medieval Sicily. In the words of Aquilina, "The Arabs are linguistically the most important people that ever managed the affairs of the country…for there is no doubt that, allowing for a number of peculiarities and erratic developments, Maltese is structurally an Arabic dialect."

- ^ a b Victor Paul Borg (2001). Malta and Gozo (illustrated ed.). Rough Guides. p. 332. ISBN 9781858286808.

- ^ Mario Buhagiar (2007). The Christianisation of Malta: catacombs, cult centres and churches in Malta to 1530 (illustrated ed.). Archaeopress. p. 83. ISBN 9781407301099.

- ^ Aa. Vv. (2007). "Introduction". Malta. Ediz. Inglese. Casa Editrice Bonechi. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9788875512026.

- ^ David Tschanz. "Malta and the Arabs". Academia.edu. p.6.

- ^ Previté-Orton, Charles William (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. pp. 507–11. ISBN 9780521209625.

- ^ Krueger, Hilmar C. (1969). "Conflict in the Mediterranean before the First Crusade: B. The Italian Cities and the Arabs before 1095". In Baldwin, M. W. (ed.). A History of the Crusades, vol. I: The First Hundred Years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 40–53.

- ^ "Arab Heritage in Malta – The Baheyeldin Dynasty". baheyeldin.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

Of greater cultural significance, the demographic and economic dominance of Muslims continued for at least another century and a half after which forced conversions undoubtedly permitted many former Muslims to remain.

- ^ Uwe Jens Rudolf; Warren G. Berg (27 Apr 2010). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of Malta (2 (illustrated) ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-8108-7390-2.

- ^ Graham A. Loud; Alex Metcalfe (1 Jan 2002). "Religious Toleration in the South Italian Peninsula". The Society of Norman Italy (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 337. ISBN 9789004125414.

- ^ Charles Dalli. From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily (PDF). p. 161. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c Martin R. Zammit (12 Oct 2012). Jørgen S. Nielsen; Jørgen Nielsen; Samim Akgönül; Ahmet Alibasi; Egdunas Racius (eds.). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, Volume 4. Malta: BRILL. p. 389. ISBN 9789004225213.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

The establishment of an Italian colony for Sicilian Muslims at Lucera on the Italian Peninsula beginning in 1223 has led to much speculation that there must have been a general expulsion of all Muslims from Malta in 1224. However, it is virtually impossible to reconcile this viewpoint with a report of 1240 or 1241 by Gilberto to Frederick II of Sicily to the effect that in that year Malta and Gozo had 836 families that were Saracen or Muslim, 250 that were Christian, and 33 that were Jewish. Moreover, Ibn Khaldun is on record as stating that some Maltese Muslims were sent to the Italian colony of Lucera around 1249.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

Though by the end of the fifteenth century all Maltese Muslims would be forced to convert to Christianity, they would still be in the process of acquiring surnames as required in the European tradition. Ingeniously, they often used their father's Arabic names as the basis of surnames, though there was a consistent cultural avoidance of extremely obvious Arabic and Muslim names, such as Muhammed and Rasul. Also, many families disguised their Arabic names, such as Karwan (the city in Tunisia), which became Caruana, and some derived family names by translating from Arabic into a Roman form, such as Magro or Magri from Dejf.

- ^ Wettinger, G. (1999). "The Origin of the 'Maltese' Surnames" (PDF). 12 (4). Melita Historica: 333.

Ibn Khaldun puts the expulsion of Islam from the Maltese Islands to the year 1249. It is not clear what happened then, except that the Maltese language, derived from Arabic, certainly survived. Either the number of Christians was far larger than Giliberto had indicated, and they already spoke Maltese or a large proportion of the Muslims themselves accepted baptism and stayed behind. Henri Bresc has written that there are indications of further Muslim political activity in Malta during the last Suabian years. Anyhow there is no doubt that by the beginning of Angevin's time, no professed Muslim Maltese remained either as free persons or even as serfs on the island.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Martijn Theodoor Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 (reprint (volume 5) ed.). BRILL. p. 214. ISBN 9789004097919.

- ^ Eltis, David; Bradley, Keith; Cartledge, Paul (2011). The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3: AD 1420-AD 1804. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-521-84068-2.

- ^ Fisher, Humphrey J. (2001). Slavery in the History of Muslim Black Africa. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-85065-524-4.

- ^ Goodwin, Stefan (2002). Malta, Mediterranean Bridge. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

- ^ Wettinger, Godfrey (2002), Slavery in the Islands of Malta and Gozo ca. 1000–1812, Publishers Enterprises Group, p. 455.

- ^ Brydone, Patrick (1813). A Tour Through Sicily and Malta. Evert Duyckinck.

- ^ Wettinger, Godfrey (2002), in Cini, George, "Horrible torture on streets of Valletta".

- ^ Sciberras, Sandro. "Maltese History – E. The Decline of the Order of St John In the 18th Century" (PDF). St. Benedict College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-89789-820-1.

Gian Francesco Abela, a patrician clergyman who eventually became the Order's [i.e., Knights Hospitaller's] vice-chancellor, also laid the foundations for Maltese historiography. Unfortunately, Abela was quite willing to distort Malta's history in the interest of deemphasizing her historic links with Africa and with Islam. Abela's determination that Malta be portrayed as innately European and Christian at all cost eventually incorporated into popular thinking about Malta's history a number of false traditions. In an eighteenth-century effort to strengthen the case for Abela's distortions and misinterpretations, a Maltese priest named Giuseppe Vella even generated forged Arabic documents. Other prominent Maltese subsequently contributed to popular folklore and legends which held that Muslims of African origin had never inhabited Malta in large numbers, including Domenico Magri, also a priest. As these distortions bore fruit and circulated within the general populace, numerous Maltese became convinced that their Semitic tongue could only have come from illustrious and pioneering Asiatic Phoenicians and not under any circumstances from neighboring Arab-speaking Africans who for reasons having to do with religion, national pride, and "race" the Maltese were more comfortable viewing as implacable enemies and inferiors . ... Though recent scholarly opinion in Malta is virtually unanimous that Malta's linguistic and demographic connections are much stronger with her Arab and Berber neighbors than [with] prehistoric Phoenicia, once out of a "Pandora's Box," legends die hard.

- ^ Mario Buhagiar. "POST MUSLIM MALTA – A CASE STUDY IN ARTISTIC AND ARCHITECTURAL CROSS-CURRENTS". Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

The Muslim past became an embarrassment and history was distorted by false traditions which determined the course of Maltese historiography till the second half of the twentieth century.

- ^ Carmel Borg; Peter Mayo (2007). "22 (Toward an Antiracist Agenda in Education: The Case of Malta)". In Gupta, Tania Das (ed.). Race and Racialization: Essential Readings. Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-55130-335-2.

- ^ Cassar, Paul (1965). Medical History of Malta. Wellcome Historical Medical Library. p. 115.

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles (2016). Medical Perspectives of Battle Conflicts in Malta. Lulu. pp. 19, 20. ISBN 9781326886936.

- ^ Wettinger, Godfrey (2002). Slavery in the Islands of Malta and Gozo ca. 1000-1812. Publishers Enterprises Group. pp. 144–172. ISBN 9789990903164.

- ^ a b Borg, Bertrand (11 February 2012). "Workmen discover a Muslim cemetery". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012.

- ^ Buttigieg, Emanuel (2018). "Early modern Valletta: beyond the Renaissance city" (PDF). In Margaret Abdilla Cunningham; Maroma Camilleri; Godwin Vella (eds.). Humillima civitas Vallettae : from Mount Xebb-er-Ras to European capital of culture. Malta Libraries and Heritage Malta. pp. 173–183. ISBN 9789993257554. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2019.

- ^ https://culture.gov.mt/en/culturalheritage/Documents/form/SCHAnnualReport2012.pdf Archived 2021-02-13 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c Hughes, Quentin; Thake, Conrad (2005). Malta, War & Peace: An Architectural Chronicle 1800–2000. Midsea Books Ltd. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9789993270553.

- ^ Grassi, Vincenza (June 1987). C. A. Nallino (ed.). "Un'Iscrizione Turca Del 1817 A Malta". Oriente Moderno. 6(67) (4–6). Istituto per l'Oriente: 99–100. doi:10.1163/22138617-0670406004. JSTOR 25817002.

- ^ Zammit, Martin R. (2012). "Malta". Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Vol. 2. BRILL. pp. 143–158. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004184756.i-712.483. ISBN 9789004184756. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019.

- ^ Grassi, Vincenza (2004). "The Turkish Cemetery at Marsa on Malta Island". Studi Magrebini. 2. Istituto Universitario Orientale: 177–201. ISSN 0585-4954.

- ^ Thake, Conrad (Summer 2000). "Emanuele Luigi Galizia (1830–1907): Architect of the Romantic Movement". The Treasures of Malta. 6 (3): 37–42. Archived from the original on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ "A close look at the Turkish cemetery". Times of Malta. 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017.

- ^ Rudolf, Uwe Jens (2018). Historical Dictionary of Malta. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 30. ISBN 9781538119181.

- ^ Galea, R. V. (1942). "The Architecture of Malta" (PDF). Scientia. 4 (1): 159, 160. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2018.

- ^ Borg, Malcolm (2001). British Colonial Architecture: Malta, 1800-1900. Publishers Enterprises Group. p. 97. ISBN 9789990903003.

- ^ a b Zammit, Martin R. (2009). "Malta". In Jørgen Schøler Nielsen; Samim Akgönül; Ahmet Alibašić; Brigitte Maréchal; Christian Moe (eds.). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Vol. 1. BRILL. p. 233. ISBN 9789004175051.

- ^ "The Mahomedan Cemetery, Malta". Mechanics' Magazine. Vol. 3, no. 11. The Canadian Patent Office Record. November 1875. pp. 343, 352.

- ^ Micallef, Keith (24 May 2019). "Plans for a 'Galizia' mosque unearthed in Ottoman archives: Small mosque had been planned within Muslim cemetery". Times of Malta.

- ^ Cordina, J. C. (2018, December 30). Islamic Centre in Malta commemorates its 40th Anniversary. The Malta Independent, pp. 37.

- ^ Uwe Jens Rudolf; Warren G. Berg (27 Apr 2010). "Introduction". Historical Dictionary of Malta (2 (illustrated) ed.). Scarecrow Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780810873902.

Whether because of their closer proximity to Italy or strong loyalty to the pope in Rome, certainly since the arrival of the Knights, the Maltese people have considered themselves to be European. This makes it all the more remarkable that the linguistic legacy of the Arab invaders survived so many centuries of Italian and European influence so that even today, the devoutly Roman Catholic population appeals to God as "Allah." Only recently have the Maltese begun to leverage their country's ability to serve as Europe's "bridge" to Arab cultures and economies of North Africa.

- ^ Jeremy Boissevain, "Ritual, Play, and Identity: Changing Patterns of Celebration in Maltese Villages," in Journal of Mediterranean Studies, Vol.1 (1), 1991:87-100 at 88.

- ^ Boissevain, Jeremy (1984). "Ritual Escalation in Malta". In Eric R. Wolf (ed.). Religion, Power and Protest in Local Communities: The Northern Shore of the Mediterranean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 166. ISBN 9783110097771. ISSN 1437-5370.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Hanspeter Mattes, "Aspekte der libyschen Außeninvestitionspolitik 1972-1985 (Fallbeispiel Malta)," Mitteilungen des Deutschen Orient-Instituts, No. 26 (Hamburg: 1985), at 88-126; 142-161.

- ^ Triq Kordin (2012). "Islamic Centre of Paola". Paola, Malta. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

This is Malta's only mosque. Also the home of the Mariam al-Batool school.

- ^ James Debono (8 December 2013). "A Muslim from Qormi: Mario Farrugia Borg". Mediatoday. MaltaToday. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Christian Peregin (7 February 2011). "Muslim and former PN councillor converts . . . to Labour". TIMES OF MALTA. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2003 – Malta". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, United States Department of State. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2011 – Malta". U.S. Department of State. 17 Nov 2010.

- ^ "Census 2021: Maltese citizens overwhelmingly identify as Roman Catholics". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

Further reading

[edit]- "The Arabs in Malta". Archived from the original (various publications by different authors on Islam in Malta) on 2022-06-26. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

Note: The following contributions to the history of the Arabs in Malta are arranged in chronological order of publication.

- Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "Chapter 2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 13–35. ISBN 9780897898201.

- Martin R. Zammit (12 Oct 2012). Jørgen S. Nielsen; Jørgen Nielsen; Samim Akgönül; Ahmet Alibasi; Egdunas Racius (eds.). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, Volume 4. Malta: BRILL. pp. 389–397. ISBN 9789004225213.