Isie Smuts

Isie Smuts | |

|---|---|

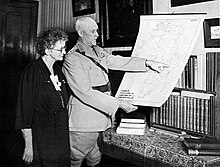

Isie and Jan Smuts, 1941 | |

| Born | Sybella Margaretha Krige 22 December 1870 Stellenbosch, Cape Colony, British Empire |

| Died | 25 February 1954 (aged 83) |

| Other names | Isie Krige, Isie Smutts |

| Occupation(s) | Teacher, farmer, First Lady of South Africa |

| Years active | 1891–1948 |

Sybella "Isie" Margaretha Smuts (née Krige, also known as Ouma Smuts; 22 December 1870 — 25 February 1954) was the second First Lady of the Union of South Africa, and a teacher, farmer, charity organiser and scrapbooker. She grew up in the British Cape Colony and qualified as a teacher in 1891. She taught for six years before marrying Jan Smuts, who later became the second Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa. She was a staunch supporter of Afrikaner nationalist aims to break free of British rule. Smuts eventually supported her husband's efforts to bring reconciliation to the Dutch and English communities and the creation of the self-governing union. During the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and World War I she supplied care parcels to inmates and soldiers. When the war ended, she was active in the Suid-Afrikaanse Vrouefederasie (South African Women's Federation), a social welfare service for war widows and orphans.

In 1909, the couple settled on the Doornkloof farm (known in English as The Big House) in Irene township outside Pretoria. She raised their six surviving children there and during her husband's extended absences on matters of state, she was the primary administrator of the farn. In the evenings when the family retired, she clipped articles from media sources written about Jan and organised them into scrapbooks. Smuts preferred to remain outside the public sphere and rarely joined her husband in any official capacity until his second term as prime minister began in 1939. She then became a leader in the Women's United Party, an affiliate of the United Party of South Africa. During World War II, she became a public figure. She spoke out against fascism and supported the creation of the Women's International Democratic Federation, an organisation aimed at preventing war and furthering women's rights. She participated in radio broadcasts and wrote articles to urge support for the war effort, accompanied her husband on troop inspection tours, brought soldiers care packages, and wrote letters for them.

In 1940, Smuts founded and chaired the Gifts and Comforts Fund, which raised money to provide servicemen with toiletries, sports equipment, and radios. Over the course of the war, the fund raised over a million pounds. Her war activities made her an icon and she became popularly known as the mother (or Ouma, grandmother) of South Africa. She received an honorary PhD from the University of the Witwatersrand in 1943 and in 1952 the South African Association of University Women created a research scholarship bearing her name. When Smuts died in 1954, her papers and scrapbook collections were donated to the South African State Archives. Microfilm copies of the Smuts Archive, which also includes Jan's records, are housed at the Universities of Cambridge and Cape Town. The Doornkloof farm was designated a National Monument by the Government of South Africa in 1969. A street in Pretoria was named in her honour.

Early life, education and family

[edit]

Sybella Margaretha Krige, known as Isie, was born on 22 December 1870 in Stellenbosch, in the British Cape Colony, to Susanna Johanna (née Schabort) and Jacob Daniël "Japie" Krige.[1][2][3] Susanna, known as Sanie, was descended from Johann Christoffel Schabort, a physician who left employment with the Dutch East India Company to immigrate to the Cape in 1714.[4] He practiced medicine until around 1745 and established two wine farms near Durbanville.[4][5] Japie was a wine and dairy farmer and the brother of Willem Krige, whose son Christman Joel Krige went on to serve as speaker of the People's Council for the Union of South Africa.[2][6][Note 1] Many members of the Krige family were politicians.[9] Piet Retief, a Voortrekker leader involved in the Great Trek, who was killed by Zulu warriors during his journey, was Japie's great uncle.[1][6] The family were Afrikaners of Dutch and Huguenot ancestry,[10] and strongly opposed British rule.[9] Krige was the second of eleven siblings, although only nine would survive.[2][3] The family lived in a Dutch-style house on the Eerste River at the end of Dorp Street.[10] Krige was encouraged by her parents to study, and was known as a bookworm. She was good at languages and enjoyed reading English, French and German literature and poetry.[11] She also played the piano and enjoyed singing.[12]

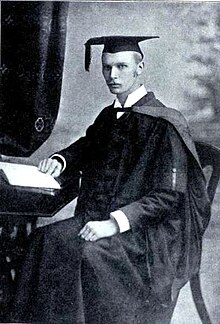

Krige attended Bloemhof Seminary in Stellenbosch.[2][13] When she was fifteen,[11] Jan Smuts, a farmer's son from Riebeek West, near Malmesbury, moved into the house of W. Ackermann,[14] a neighbour and friend of the Krige family.[9][11] Jan was a serious student at Victoria College,[10][11] and the two met while walking to school. They developed a habit that Jan would accompany Krige to school in the morning and back home in the afternoon.[9] The two had much in common: both were shy and reserved, both enjoyed walking and discussing literature and botany,[9][10] and they liked to sing together.[12] Jan even tutored her in Greek.[10] Krige wanted to become a physician but the family's financial situation did not allow for such a long period of study.[15] Instead, after passing the entrance exam in 1887 for Victoria College,[16] Krige graduated in 1891 and began teaching in a rural school,[15][17] where she earned £5 a month.[18] Jan graduated in science and literature in 1891 and was awarded the Ebden Scholarship to study law at the University of Cambridge.[19] While he was abroad, they wrote to each other regularly.[15] He passed his bar examination in England in 1894, and after turning down an offer to become a professor, returned to the Cape Colony.[20]

Failing to establish a successful law practice in the Cape Colony, in 1896 Jan moved to the Transvaal Colony.[21][22] He made trips back to visit his parents and Krige,[23] and on 30 April 1897 in Stellenbosch, he and Krige married.[4][23] They immediately left to return to Johannesburg and established their home on Twist Street.[24] On 5 March 1898, Smuts gave birth to premature twins, Koosie and Jossie, who lived less than a month.[25][26][27] Within three months, the couple moved to Pretoria, when Jan became the State Attorney of the Transvaal.[28] They had another son, Jacobus Abraham (known as Koosie), on 16 April 1899,[25][27] and before the end of the year, Smuts published A Century of Wrong, an English translation of her husband's co-written work Een Eeuw van Onrecht.[25][29][Note 2] The book recounted the perceived injustices the Boers had experienced at the hands of the British.[25][31] Within weeks, the Second Boer War broke out and Jan was one of the defenders of Pretoria when it was captured by the British in June 1900.[32] Jan subsequently went to the front. On 14 August their son died.[29][33][27] After her son's death, the British sent Smuts, her younger sister and a friend to Pietermaritzburg, in the Colony of Natal. Despite her wish to be held with other women in the nearby concentration camp, Smuts and her party lived in a house. They frequently visited the camp to console the inmates and bring them items they had knitted.[34] In 1902, at the end of the war the couple reunited in Pretoria[35] and by 1914 had six children.[36]

Politician's wife

[edit]

At the conclusion of the war, the Treaty of Vereeniging established the supremacy of the British, bringing all White South Africans under The Crown's authority.[37] The treaty established that English would be the official administrative language and the only language used in schools. It also provided that at a future point the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies would be allowed to self-govern, but contained no provisions for native-born people to vote until they became self-governing.[38][Note 3] Although Jan worked to end the conflict and bring reconciliation to British and Afrikaner settlers, Smuts remained hostile towards the British. She feared that the Dutch would be treated unfairly under British rule and according to the writer Helen Bradford, Smuts preferred annihilation over capitulation.[40] Jan refused to accept a position on the Legislative Council of the Transvaal and along with others continued to press for full self-governance.[41] In 1906, he went to England to try to convince British legislators to grant self-rule and revise the method of allowing only propertied individuals to vote.[42] He was successful in arguing for new voting laws, and in December suffrage was granted to all White European men over the age of twenty-one. Neither non-Europeans nor women were allowed to vote.[43] The election the following year led to a new government with Jan serving as the Colonial Secretary.[44] By 1908, all three British colonies – Cape, Orange River, and the Transvaal – had achieved self-governance,[45] and over the next two years negotiations continued for the formation of the Union of South Africa.[46] The Union was inaugurated on 31 May 1910,[47] and included the three colonies and the Natal Colony.[48][49] With the creation of the Union, Smuts' hostility towards the British eased as she recognised that the two Dutch colonies of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal would balance the Union with the two British colonies of Cape and Natal.[49]

After the Union was created, a period of socio-economic unrest ensued. Smuts publicly endorsed her husband's policies in an effort to reduce the perception that he was against Afrikaner nationalist aims. The historian Suryakanthie Chetty stated that Smuts had become known as "Tante Isie" (aunt Isie) and was popularly viewed as a plain-spoken, humble country wife, as opposed to a sophisticated city dweller.[50] She became active in the welfare work of the Suid-Afrikaanse Vrouefederasie (South African Women's Federation),[16] an organisation founded in 1904 by Annie Botha and Georgiana Solomon to assist destitute widows and war orphans.[51][52] In 1909, the couple moved to a farm in Irene township, outside Pretoria, covering 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), where Jan relocated a former military mess hall and renovated it into a home that came to be known as Doornkloof (and in English The Big House).[53] The house was made of tin to prevent ants from demolishing it, and was modest in comparison with other statesmen's residences.[54] It contained a huge library of around 6,000 books in "Afrikaans, Dutch, English, French, German, Hebrew, Latin, and Greek", on a wide variety of subjects, including botany, ethics, evolution, and philosophy.[55] When Parliament was in session, Jan lived at Groote Schuur, near Cape Town,[56] but Smuts remained at Doornkloof, preferring to avoid politics and remain in the background.[16][57] Jan's long absences meant that she was the primary person overseeing the farming activities and tending the bee hives.[58][59] Doornkloof was where they raised their children, Susanna Johanner (14 August 1903, known as Santa), Catharina Petronella (3 December 1904, called Cato), Jacob Daniel (17 July 1906 – 10 October 1948, known as Japie), Sybella Margaretha (27 July 1908, called Sylma), Jan Christian (15 August 1912, known as Jannie), Louis Anne de la Rey (1 November 1914,[27][60] a daughter named after Louis Botha and Koos de la Rey), and an adopted daughter Kathleen de Villiers.[61][62] In addition to running the household, Smuts organised a massive collection of articles written about Jan.[Note 4] Her scrapbooking activities frequently took place at night after the family had retired.[61] She also dealt with the hate mail regularly received at the farm from many Afrikaners who felt that Jan had betrayed his own people by reconciling with the British.[63][64]

Personal style

[edit]Smuts was known to be extremely frugal, never possessing more than three dresses at any one time throughout her life.[65] She preferred to be barefooted, only wearing shoes when attending a party or in Cape Town at a parliamentary function.[66] Known for her frankness and humour,[67][68] her personal correspondence reveals that she was "lively, intelligent, and humane", according to Keith Hancock and Jean van der Poel, the historians who compiled the family archival records.[69] She and Jan typically spoke Afrikaans to each other,[61] and their letters to each other and their children throughout their lives were written in Afrikaans, except in the period of the Boer War when they wrote in English, possibly to avoid censorship.[70] Jan had a habit of creating friendships and flirtations with other women,[57][71] and admitted that he found women more interesting than men.[72] The Rhodes scholar and journalist Piet Beukes, who published The Romantic Smuts: Women and Love in his Life (1992) concluded that his wife was always the "object of his most intimate affection"[73] and that his only "love letters" were written to his wife.[74] Jan denied that any of his other relationships were sexual in nature.[75][76] Smuts rarely revealed her own thoughts about his friendships.[77] In general, she avoided publicity,[67] insisting that her husband was the historically important figure.[78]

Smuts was unpretentious and preferred to be informal when extending hospitality to guests.[65] She was unimpressed by high society or fame, and although she entertained numerous dignitaries, she welcomed them cordially without any fanfare.[57][67] For example, in mid-1941 Crown Princess Frederika of Greece sought refuge in South Africa after the Nazi invasion of Greece. Shortly after her arrival, the Smuts invited her and her husband Crown Prince Paul, their children Constantine and Sophia, her brother-in-law George II of Greece, her sister-in-law Princess Katherine and other members of their party to a luncheon at Libertas, Jan's official residence in Pretoria.[79] A few weeks later, Jan announced that the party would arrive that afternoon for tea at Doornkloof. Smuts and her daughters frantically attempted to straighten the farmhouse and hid some of the clutter under the furniture in the small sitting room. The guests arrived and to accommodate everyone the furniture was moved, exposing their secret stash. Nonplussed, Smuts was able to hold a successful tea party.[80] Likewise in 1947 when George VI, Queen Elizabeth, and their daughters Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret came from Britain to South Africa, Smuts explained that she was too ill to travel to Cape Town. The queen's response was that they would simply come to visit at Doornkloof.[81]

War relief efforts (1914–1945)

[edit]When World War I broke out in 1914, Jan, acting as Minister of Defence, called out volunteer regiments and members of the Union Defence Force within a week of Britain's declaration of war. Although there was opposition to South African participation in another British war, Louis Botha, the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa and Jan organised troops to meet the call of the British for an invasion of German South West Africa.[82] By 1915, Jan was away and involved in the campaign,[83] and then spent two and a half years based in England,[84] also travelling to Egypt, Italy, and Switzerland to plan campaigns or explore peace options for the British war department.[85] Smuts wrote to him frequently to keep him informed of political developments in South Africa.[86] She also regularly visited wounded soldiers at the hospitals around Pretoria, bringing them care parcels. When the war ended, Jan returned home and in 1919 became the second Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa.[63] On losing the office in 1924, he became the Leader of the Opposition,[87] serving until 1933, when he became deputy prime minister.[88] In 1939, the coalition that wanted South Africa to support the allies won the vote and he was reinstalled as prime minister.[63] Jan came to office as the leader of the United Party[89] and Smuts became a leader of its women's auxiliary, known as the Women's United Party.[13]

By the time Jan had begun his second term as prime minister, women in the Union of South Africa had won the right to vote. The vote was extended to women in 1930 as a means of expanding the White electorate, rather than as a result of agitation for gender equality. Smuts was in favour of granting suffrage to women, if it did not interfere with their roles as mothers whose work was in the home. She was conservative and believed that racial and social hierarchies were necessary for maintaining order.[90] Supporting policies of racial segregation, her attitude towards Black South Africans was paternalistic and she treated her Black staff as if they were children. Her husband aimed to make the Union of South Africa "the mother of white civilisation in the continent."[91] Smuts' conservative views extended to women's and Blacks' participation when they were called to support the war effort in World War II. Neither group was allowed to serve as combatants, and both groups were limited to supporting roles.[92] When the war broke out, a radical fascist segment of the White Afrikaner community gained adherents who sympathised with the Nazi Party's ideology of Germanic people's racial superiority.[93] When the Ossewabrandwag, a right-wing, paramilitary, Afrikaner nationalist group took part in demonstrations and acts of sabotage,[94] Smuts stressed the need for the country to unite in the fight against fascism.[94][95] In 1945, she sent a letter of support to the women founding the Women's International Democratic Federation, an anti-fascist organisation intent on preventing war and improving women's rights.[96]

Smuts became a public figure during the war.[13] She and Jan were portrayed by the media as the mother and father of the country.[91] In a radio broadcast, the couple launched the 'gold fund', a project which encouraged the donation of gold jewellery to fund the war effort.[94] In 1940, she founded and chaired the Gifts and Comforts Fund, an initiative operated at the national level to raise funds for the war effort. By 1942, £158,000 had been collected,[13] and by the end of the war the fund had raised over a million pounds.[97] The fund distributed items such as sports equipment and radios to give servicemen comforts from home and something to do when they were not fighting.[98] Smuts personally sewed toiletries bags, wrote articles for The Women's Auxiliary, gave speeches, and went on troop inspection tours with Jan.[99] On one such trip in Egypt in 1942, she visited soldiers in their camps and in hospital and supervised the delivery of parcels to them.[13] She organised a tea and poured it for the servicemen herself. She also wrote letters for them to their loved ones.[92] She campaigned for the welfare of prisoners of war and participated in the launch of the Governor-General's War Fund.[13] Over the course of the war, Smuts became an icon, especially for the soldiers fighting abroad, and was known affectionately as "ouma" (grandmother).[100] In 1941, Jan had a South African woman sculptor create a bust of Smuts to memorialise her success as a public figure.[66] While they were in Egypt, the English painter Simon Elwes painted portraits of the couple.[66][101] Jan proclaimed Elwes's portrait of his wife a masterpiece.[66] In 1943, her war work was honoured by the University of the Witwatersrand, which granted her an honorary PhD in philosophy.[13][102] The following year, in honour of her 74th birthday, dignitaries from Britain, South Africa, and the United States hosted a campaign,[97] Ouma's Birthday Appeal, which included radio broadcasts from celebrities,[78] and raised around £200,000.[97] In 1946, the Welsh writer Tom Macdonald, wrote Ouma Smuts: The First Lady of South Africa, based on interviews with Smuts and other documentation.[103][104]

Later years, death and legacy

[edit]The war led to socio-economic transformation in South Africa as factories expanded for wartime production. Black and White workers were employed in the factories, which meant that previous strict segregation policies were no longer in force. For the first time, large numbers of Blacks moved into the cities, outnumbering the White urban population.[105] In 1943, the African National Congress presented Jan with a demand for full citizenship rights and the ability for Blacks to participate in the governance of the country.[106] He did not respond[107] and dissent and protest from Blacks continued. When the war ended he acknowledged that economic growth required Black labourers and that migration to the cities needed to be addressed, although he was unwilling to give Blacks political rights. The Herenigde Nasionale Party took the opposite view, arguing that Blacks should be sent back to the countryside and segregated into their traditional societies.[108] In the 1948 elections, the United Party was defeated, Jan lost his office and White South African voters brought the Herenigde Nasionale Party to power.[109] Their victory brought with it the formalisation of apartheid. Jan retired to Doornkloof, where he died in 1950.[110] Smuts was honoured in 1952 by the South African Association of University Women, creating a research scholarship in her name.[111] She died on 25 February 1954 at Doornkloof and was cremated. Her ashes were spread across their farmlands.[13]

Upon her death, in accordance with the terms of her will, her official and personal papers,[112] apart from her letters to Jan which she had destroyed,[69] were given to the State Archives in Pretoria. These also included some of Jan's papers, but not the documents she had destroyed as a safety measure before the British siege of Pretoria in the Boer War.[112] Jan's papers had been housed temporarily at the Jagger Library at the University of Cape Town for the collection to be organised, catalogued, and supplemented by donations of correspondence from people he had written to, as Jan had not made copies of his outgoing mail.[113] The Smuts Archive Trust was established to curate the collections, join them into one archive and provide for their preservation in the State Archives.[112] Two microfilm copies of the materials were prepared and housed at the Universities of Cambridge and Cape Town.[114] Smuts' correspondence with the South African author Olive Schreiner, written between 1899 and 1917, is included in The Olive Schreiner Letters Online project, organised by professor Liz Stanley of the University of Edinburgh.[115] Their correspondence mainly focuses on war relief efforts after the Boer War, although they also describe their personal relationship and political differences.[16]

Six years after Smuts' death a developer attempted to purchase Doornkloof to turn it into a sanatorium. To prevent the loss of the historic site, the Pretoria attorney Guy Brathwaite purchased the house and 25 morgen of land (around 50 acres (20 ha)), from Kitty, widow of Smuts's oldest son Japie, for £7,000.[116] Gathering ex-servicemen at a conference, Brathwaite proposed the establishment of the General Smuts War Veterans' Foundation to preserve the property as a memorial.[117] The house was restored and plans were made to plant indigenous trees and shrubs on the property to create a nature park, preserving the botanical specimens in the wild gardens the Smuts had designed.[118] In 1969, the Government of South Africa declared the property a National Monument.[119] Isie Smuts Street in Constantia Park, Pretoria, is named in her honour.[120]

According to Chetty, a study of Smuts' life provides understanding of the changes underway in South Africa caused by the three wars which occurred in the first half of the twentieth century. Her life represents the conservative view of women's supportive roles as wives and mothers, and their sacrifices for the nation.[110] Smuts' evolution from a staunch supporter of Afrikaner nationalism to support for the British and recognizing a nation built of both Dutch and British White citizens contrasted with the large segment of Afrikaners who were unable to accept reconciliation with the British. Her paternalistic attitude towards Black South Africans conflicted with the demands of the majority section of the population which had begun to demand political recognition.[121] The Second World War caused socio-economic shifts in South Africa that brought the demands of Afrikaner and Black South Africans to a head, giving birth to the apartheid state.[122]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The biographies from the Smuts House Museum call Joel her uncle,[2] whereas, Levi states the speaker of the council was the son of Japie's brother W. Krige.[6] Joel's baptismal record confirms his father was Willem Adolf Krige.[7] Swart's entry in the Dictionary of South African Biography states she and Joel were cousins.[8]

- ^ The biographies from the Smuts House Museum say that she translated the work into Dutch from English,[2] but the introduction written by H. J. Kiewiet de Jonge to the 1899 book, Een Eeuw van Onrecht, states that the authors are Francis William Reitz and Jan Christian Smuts.[30]

- ^ Alfred Milner, High Commissioner for South Africa and Governor of the Transvaal,[37] established the governing policy which per his writings intended to delay self-rule until such time as there were more British inhabitants than Dutch inhabitants. In his doctrine, a strict racial hierarchy would eventually allow non-British White communities to gain equality, but the Black population would not attain political rights.[39]

- ^ There were 110 scrapbooks created by Smuts which documented Jan's career through March 1940, alone.[61]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Chetty 2015, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f Smuts House Museum 2023.

- ^ a b Cameron 1994, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Lean 1965, p. 267.

- ^ Laidler 1971, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Levi 1917, p. 15.

- ^ Baptismal record 1868, p. 11.

- ^ Swart 1981, pp. 585–586.

- ^ a b c d e Armstrong 1939, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Crafford 1943, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d The War Cry 1947, p. 11.

- ^ a b Hancock 1962, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Swart 1981, p. 585.

- ^ Crafford 1943, pp. 4–5, 9.

- ^ a b c Chetty 2015, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Stanley 2012.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 62.

- ^ Hancock 1962, p. 62.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 11.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 12.

- ^ Armstrong 1939, p. 43.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 20.

- ^ a b Crafford 1943, p. 21.

- ^ Crafford 1943, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c d Chetty 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Hancock 1962, p. 167.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 24.

- ^ a b Smuts 2009, p. 65.

- ^ Kiewiet de Jonge 1899, p. Inleiding.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 34.

- ^ Crafford 1943, p. 37.

- ^ Millin 1936, p. 138.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Millin 1936, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Thompson 1961, p. 4.

- ^ Thompson 1961, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Thompson 1961, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 45.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 21.

- ^ Thompson 1961, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 26.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 28.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 30.

- ^ Thompson 1961, pp. 205–209, 360–361, 368–372.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 416.

- ^ Thompson 1961, p. 396.

- ^ a b Chetty 2015, p. 46.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 47.

- ^ van Heyningen 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Gordon 1988, p. 252.

- ^ Lean 1965, p. 268.

- ^ Busch 1944, p. 64.

- ^ Meredith 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Busch 1944, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Ingham 1986, p. 16.

- ^ Smuts 2009, pp. 71, 73.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 87.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Busch 1944, p. 67.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Chetty 2015, p. 48.

- ^ Meredith 1988, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Hancock 1962, p. 281.

- ^ a b c d Hancock 1968, p. 391.

- ^ a b c Levi 1917, p. 152.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 6.

- ^ a b van der Poel & Hancock 1966, p. ix.

- ^ Hancock 1962, p. 132.

- ^ Steyn 2015, Search phrase "Ethel Brown".

- ^ Steyn 2015, Search phrase "women are more interesting".

- ^ Steyn 2015, Search phrase "object of his most intimate affection".

- ^ Beukes 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Beukes 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 83.

- ^ a b Smuts 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Hancock 1968, p. 402.

- ^ Hancock 1968, p. 403.

- ^ Hancock 1968, p. 495.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 77.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 80.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 89.

- ^ Ingham 1986, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Ingham 1986, p. 111.

- ^ Lean 1965, p. 271.

- ^ Smuts 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Walker 1982, p. 72.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 49.

- ^ a b Chetty 2015, p. 51.

- ^ a b Chetty 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Chetty 2015, p. 52.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, pp. 39–40.

- ^ de Haan 2012, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b c Chetty 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Roos 2011, p. 823.

- ^ Chetty 2015, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Swart 1981, p. 586.

- ^ Hancock 1968, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Howells-Jones 1946, p. 2.

- ^ The Toronto Star 1946, p. 23.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, p. 35.

- ^ a b Chetty 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Journal of the AAUW 1952, p. 176.

- ^ a b c van der Poel & Hancock 1966, p. vii.

- ^ van der Poel & Hancock 1966, pp. v–vi.

- ^ van der Poel & Hancock 1966, p. viii.

- ^ Olive Schreiner Letters 2012.

- ^ Lean 1965, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Lean 1965, p. 275.

- ^ Lean 1965, p. 276.

- ^ Staatskoerant 1969, p. 11.

- ^ Staatskoerant 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Chetty 2015, p. 56.

- ^ Clark & Worger 2016, pp. 36–40.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Arcadia Pretoria". Staatskoerant. Vol. 601, no. 39021. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printing Works. 24 July 2015. p. 15. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- Armstrong, H. C. (1939). Grey Steel (J. C. Smuts): A Study in Arrogance. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. OCLC 1072004158.

- "Baptismal Records of the Dutch Reformed Church: Chrisman Joël Ackerman Krige". FamilySearch. Cape Town, South Africa: Cape Town Archives of the Dutch Reformed Church. March 1868. p. 11. Retrieved 25 November 2023.(subscription required)

- Beukes, Piet (1992). The Romantic Smuts: Women and Love in His Life. Cape Town, South Africa: Human & Rousseau. ISBN 978-0-7981-2984-8.

- "Biographies of Jan and Isie Smuts". Smuts House Museum. Centurion, South Africa: General Smuts Foundation. 2023. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- Busch, Noel F. (1944). My Unconsidered Judgement. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Cameron, Trewhella (1994). Jan Smuts: An Illustrated Biography. Cape Town, South Africa: Human & Rousseau. ISBN 978-0-7981-3343-2.

- Chetty, Suryakanthie (July 2015). "Mothering the 'Nation': The Public Life of Isie 'Ouma' Smuts, 1899-1945". African Historical Review. 47 (2). Pretoria, South Africa: Unisa Press: 37–57. doi:10.1080/17532523.2015.1130189. ISSN 1753-2523. OCLC 6057356271. Retrieved 25 November 2023. – via Taylor & Francis (subscription required)

- Clark, Nancy L.; Worger, William H. (2016). South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid (3rd ed.). New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-96323-8.

- Crafford, F. S. (1943). Jan Smuts: A Biography. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co. OCLC 808356903.

- "Declaration of a National Monument" (PDF). Staatskoerant. No. 2551. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printing Works. 31 October 1969. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- de Haan, Francisca (2012). The Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF): History, Main Agenda, and Contributions, 1945–1991 (Report). Alexandria, Virginia: Alexander Street Press. Retrieved 9 December 2015. – via ASP: Women and Social Movements (subscription required)

- Gordon, Ruth E. (1988). Petticoat Pioneers: Women of Distinction. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: Shuter & Shooter Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7960-0135-1.

- Hancock, William Keith (1968). Smuts: The Fields of Force 1919-1950. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 28941911.

- Hancock, William Keith (1962). Smuts: The Sanguine Years 1870 – 1919. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 32802110.

- Howells-Jones, W. (7 May 1946). "Reviews of Books: First Lady of South Africa". Western Mail. Cardiff, Wales. p. 2. Retrieved 29 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ingham, Kenneth (1986). Jan Christian Smuts: The Conscience of a South African. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-43997-2.

- Kiewiet de Jonge, H. J. (1899). "Inleiding [Introduction]". In Reitz, F. W.; Smuts, J. C. (eds.). Een eeuw van onrecht [A Century of Wrong] (in Dutch). Dordrecht, Eastern Cape: Morks & Geuze. OCLC 680538941.

- Laidler, Percy Ward (1971). South Africa: Its Medical History 1652–1898 – A Medical and Social Study. Cape Town, South Africa: C . Struik (Pty), Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86977-003-0.

- Lean, Phyllis S. (December 1965). "He Found Peace at Doornkloof". Historia (10). Durban, South Africa: Historical Association of South Africa: 265–277. hdl:10520/AJA0018229X_1000. ISSN 0018-229X. OCLC 5878344203. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- Levi, N. (1917). Jan Smuts: Being a Character Sketch of Gen. The Hon. J. C. Smuts, K.C., M. L.A., Minister of Defence, Union of South Africa. London, UK: Longman Green & Company. OCLC 827603083.

- "Meet the Editorial Team". The Olive Schreiner Letters Online. Edinburgh, Scotland: Olive Schreiner Organization. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- Meredith, Martin (1988). In the Name of Apartheid: South Africa in the Postwar Period. New York, New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-435659-6.

- Millin, Sarah Genrtrude (1936). General Smuts. London, UK: Faber and Faber. OCLC 180646698.

- Smuts, Carisa (January 2009). A Psychobiographical Study of Isie Smuts (PDF) (Magister Artium). Summerstrand, South Africa: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- "Ouma Smuts". Toronto Star. Toronto, Ontario. 25 May 1946. p. 23. Retrieved 29 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roos, Neil (Spring 2011). "Education, Sex and Leisure: Ideology, Discipline and the Construction of Race among South African Servicemen during the Second World War". Journal of Social History. 44 (3). Fairfax, Virginia: George Mason University Press: 811–835. ISSN 0022-4529. JSTOR 41305382. OCLC 5183800582. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- Stanley, Liz, ed. (2012). "Isie Smuts (nee Krige)". The Olive Schreiner Letters Online. Edinburgh, Scotland: Olive Schreiner Organization. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- Steyn, Richard (2015). Jan Smuts: Unafraid of Greatness. Cape Town, South Africa: Jonathan Ball Publishers. ISBN 978-1-86842-695-9.

- Swart, M. J. (1981). "Smuts, Sybella (Isabelle, Is(s)ie) Margaretha". In Beyers, C. J. (ed.). Dictionary of South African Biography. Vol. 4 (1st ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. pp. 585–586. ISBN 978-0-409-09183-0. OCLC 1000639607.

- "The African Federation Story". Journal of the American Association of University Women. 45 (3). Ithaca, New York: American Association of University Women: 174–176. March 1952. ISSN 2767-5521. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- Thompson, Leonard Monteath (1961). The Unification of South Africa, 1902–1910 (Reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. OCLC 81824205.

- van der Poel, Jean; Hancock, William Keith (1966). "Preface". In Smuts, Jan Christiaan; Smuts, Isie (eds.). Selections from the Smuts Papers. Vol. 1: June 1886 – May 1902. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. v–xi. OCLC 174858693.

- van Heyningen, Elizabeth (2007). "4. Women and Gender in the South African War, 1899–1902". In Gasa, Nomboniso (ed.). Women in South African History: They Remove Boulders and Cross Rivers (1st ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. pp. 91–125. ISBN 978-0-7969-2174-1.

- Walker, Cherryl (1982). Women and Resistance in South Africa (1st ed.). London, UK: Onyx Press. ISBN 978-0-906383-14-8.

- "Wife of a Great Statesman". The War Cry. No. 3283. Toronto, Ontario: The Salvation Army. 25 October 1947. p. 11. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- 1870 births

- 1954 deaths

- United Party (South Africa) politicians

- South African philanthropists

- South African human rights activists

- South African women philanthropists

- South African women farmers

- Community activists

- South African farmers

- Spouses of prime ministers of South Africa

- First ladies of South Africa

- People from Stellenbosch

- Prisoners and detainees of the British military