Hush harbor

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

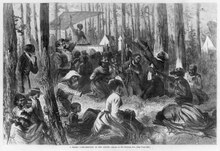

During antebellum America, a hush harbor was a place where enslaved African Americans would gather in secret to practice religious traditions.[1]

History

[edit]

Religion grew to become a highly respected part of life for enslaved Africans. It offered them hope and reassurance, although they were forced to organize and conduct meetings in secret because the idea of assembling without supervision left the slaveowners in fear. The meetings were held after dark, once field and house chores were completed, and carried on late into the night.[4][5][6]

Christianity became the prominent religion of enslaved Africans after being transported to the Americas. Upon exposure to Christianity, the enslaved discovered promising stories and passages in the Bible that offered hope; the suffering of Jesus Christ was relatable to their existence. [7][8][9]

The hush harbors served as the location where the enslaved could combine their African religious traditions with Christianity. It was safe to freely blend the components of each religion in these meetings.[10] The enslaved could let go of all their hardships and express their emotions. Here is where Negro spirituals originated; the creation of these songs contained a double meaning, revealing the ideas of religious salvation and freedom from slavery. The meetings would also include practices such as dance. African shouts and rhythms were also included.

The enslaved would suffer punishments had they been caught in a hush harbor meeting. Slave owners were confident that they would compare treatment, working conditions, and punishments, leaving them worried about revolts and riots. Instead the African American church focused on the message of equality, teaching that all people were equal in God's eyes, and on hopes for a better future.[11]

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W. E. B. Du Bois) studied African-American churches in the early twentieth century. Du Bois asserts that the early years of the Black church during slavery on plantations was influenced by Voodooism.[12] For example, an oral account from an African American in the nineteenth century revealed that African Americans identified as Christian but continued to make and carry mojo bags to church and practiced Hoodoo and Voodoo. As time progressed, many African Americans became more Christian and less influenced by African religions.[13][14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cornelius, Janet Duitsman (1999-01-01). Slave Missions and the Black Church in the Antebellum South. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570032479.

- ^ Raboteau (7 October 2004). Slave Religion The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802031-8.

- ^ Wortham, Robert (2017). W. E. B. Du Bois and the Sociology of the Black Church and Religion, 1897–1914. Lexington Books. p. 153. ISBN 9781498530361.

- ^ Louisiana State Museum Staff (27 January 2014). "Religion, Race, and Slavery". Louisiana State Museum. Louisiana Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Maffly-Kipp, Laurie F. "An Introduction to the Church in the Southern Black Community". Documenting the American South. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Smithsonian Staff. "The Historical Legacy of Watch Night". National Museum of African American History and Culture. Smithsonian. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Maffly-Kipp, Laurie F. "An Introduction to the Church in the Southern Black Community". Documenting the American South. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Raboteau (7 October 2004). Slave Religion The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 215–220. ISBN 978-0-19-517413-7.

- ^ Bromley, David G. "Historical Context of African American Religion". Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Gooden, Mario (2016-02-23). Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City. ISBN 9781941332139.

- ^ "African American Christianity, Pt. I: To the Civil War, the Nineteenth Century, Divining America: Religion in American History, TeacherServe, National Humanities Center".

- ^ Wortham, Robert (2017). W. E. B. Du Bois and the Sociology of the Black Church and Religion, 1897–1914. Lexington Books. p. 153. ISBN 9781498530361.

- ^ Pinn, Anthony (2017). Varieties of African American Religious Experience Toward a Comparative Black Theology - 20th Anniversary Edition. Fortress Press. p. xxviii. ISBN 9781506403366.

- ^ Louisiana State Museum Staff (27 January 2014). "Religion, Race, and Slavery". Louisiana State Museum. Louisiana Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2021.