History of the Shakespeare authorship question

Claims that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works traditionally attributed to him were first explicitly made in the 19th century.[1] Many scholars consider that there is no evidence of his authorship ever being questioned prior to then.[b][3] This conclusion is not accepted, however, by proponents of an alternative author, who discern veiled allusions in contemporary documents they construe as evidence that the works attributed to him were written by someone else,[4] and that certain early 18th-century satirical and allegorical tracts contain similar hints.[5]

Throughout the 18th century, Shakespeare was described as a transcendent genius and by the beginning of the 19th century Bardolatry was in full swing.[6] Uneasiness about the difference between Shakespeare's godlike reputation and the humdrum facts of his biography continued to emerge in the 19th century. In 1853, with help from Ralph Waldo Emerson, Delia Bacon, an American teacher and writer, travelled to Britain to research her belief that Shakespeare's works were written by a group of dissatisfied politicians, in order to communicate the advanced political and philosophical ideas of Francis Bacon (no relation). Later writers such as Ignatius Donnelly portrayed Francis Bacon as the sole author. After being proposed by James Greenstreet in 1891, it was the advocacy of Professor Abel Lefranc, a renowned authority on Renaissance literature, which in 1918 put William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby in a prominent position as a candidate.[7]

The poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe was first proposed as a member of a group theory by T.W. White in 1892. This theory was expanded in 1895 by Wilbur G. Zeigler, where he became the group's principal writer.[8] Other short pieces supporting the Marlovian theory appeared in 1902,[9] 1916[10] and 1923,[11] but the first book to bring it to prominence was Calvin Hoffman's 1955 The Man Who Was Shakespeare.[12]

In 1920, an English school-teacher, J. Thomas Looney, published Shakespeare Identified, proposing a new candidate for the authorship in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. This theory gained many notable advocates, including Sigmund Freud, and since the publication of Charlton Ogburn's The Mysterious William Shakespeare: the Myth and the Reality in 1984, the Oxfordian theory, boosted in part by the advocacy of several Supreme Court justices, and high-profile theatre professionals, has become the most popular alternative authorship theory.[13][14]

Alleged early doubts

[edit]

The overwhelming majority of mainstream Shakespeare scholars agree that Shakespeare's authorship was not questioned during his lifetime or for two centuries afterward. Jonathan Bate writes, "No one in Shakespeare's lifetime or the first two hundred years after his death expressed the slightest doubt about his authorship."[2] Proponents of alternative authors, however, claim to find hidden or oblique expressions of doubt in the writings of Shakespeare's contemporaries and in later publications.

In the early 20th century, Walter Begley and Bertram G. Theobald claimed that Elizabethan satirists Joseph Hall and John Marston alluded to Francis Bacon as the true author of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece by using the sobriquet "Labeo" in a series of poems published in 1597–8. They take this to be a coded reference to Bacon on the grounds that the name derives from Rome's most famous legal scholar, Marcus Labeo, with Bacon holding an equivalent position in Elizabethan England. Hall denigrates several poems by Labeo and states that he passes off criticism to "shift it to another's name". This is taken to imply that he published under a pseudonym. In the following year Marston used Bacon's Latin motto in a poem and seems to quote from Venus and Adonis, which he attributes to Labeo.[15][16] Theobald argued that this confirmed that Hall's Labeo was known to be Bacon and that he wrote Venus and Adonis. Critics of this view argue that the name Labeo derives from Attius Labeo, a notoriously bad Roman poet, and that Hall's Labeo could refer to one of many poets of the time, or even be a composite figure, standing for the triumph of bad verse.[17][18] Also, Marston's use of the Latin motto is a different poem from the one which alludes to Venus and Adonis. Only the latter uses the name Labeo, so there is no link between Labeo and Bacon.[17]

In 1948 Charles Wisner Barrell argued that the "Envoy", or postscript, to Thomas Edward's poem Narcissus (1595) identified the Earl of Oxford as Shakespeare. The Envoy uses allegorical nicknames in praising several Elizabethan poets, among them "Adon". This is generally accepted to be an allusion to Shakespeare as the mythical Adonis from his poem Venus and Adonis. In the next stanzas, Edwards mentions a poet dressed "in purple robes", "whose power floweth far." Since purple is, among other things, a symbol of aristocracy, most scholars accept that he is discussing an unidentified aristocratic poet.[citation needed] Barrell argued that the stanzas about Adon and the anonymous aristocrat must be seen together. He stated that Edwards is revealing that Adon (Shakespeare) is really the Earl of Oxford, forced by the Queen to use a pseudonym.[19] Variations on Barrell's argument have been repeated by Diana Price and Roger Stritmatter.[20] Brenda James and William D. Rubinstein argues that the same passage points to Sir Henry Neville.[21] Mainstream scholars assert that Edwards is discussing two separate poets, and it has also been suggested that (as in the final stanzas of Venus and Adonis) the purple refers to blood, with which his garments are "distain'd", and that the poet could be Robert Southwell, under torture in the Tower of London.[22]

Many other passages supposedly containing hidden references to one or another candidate have been identified. Oxfordian writers have found ciphers in the writings of Francis Meres.[23] Marlovian Peter Farey argues that the poem on Shakespeare's monument is a riddle asking who is "in this monument" with Shakespeare, the answer to which is "Christofer Marley", as Marlowe spelt his own name.[24]

Various anti-Stratfordian writers have interpreted poems by Ben Jonson, including his prefatory poem to the First Folio, as oblique references to Shakespeare's identity as a frontman for another writer.[25] They have also identified him with such literary characters as the laughingstock Sogliardo in Jonson's Every Man Out of His Humour, the literary thief poet-ape in Jonson's poem of the same name, and the foolish poetry-lover Gullio in the university play The Return from Parnassus. Such characters are taken as evidence that the London theatrical world knew Shakespeare was a mere front for an unnamed author whose identity could not be explicitly given.[17][26]

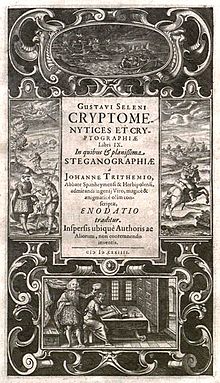

Visual imagery, including the Droeshout portrait has also been claimed to contain hidden messages.[27] Edwin Durning-Lawrence asserts that "there is no question – there can be no possible question – that in fact it is a cunningly drawn cryptographic picture, shewing two left arms and a mask ... Especially note that the ear is a mask ear and stands out curiously; note also how distinct the line shewing the edge of the mask appears." Durning-Lawrence also claims that other engravings by Droeshout "may be similarly correctly characterised as cunningly composed, in order to reveal the true facts of the authorship of such works, unto those who were capable of grasping the hidden meaning of his engravings."[28] R.C. Churchill notes that Baconians have often claimed to find secret meanings in the imagery of the title pages and frontispieces of 17th-century books, such as the 1624 book Cryptomenytices et Cryptographiae, by Gustavus Selenus (a pseudonym of the Duke of Brunswick), or the 1632 edition of Florio's translation of Montaigne.[29]

Alleged 18th-century allusions

[edit]R. C. Churchill says that the first documented expression of doubt about Shakespeare's authorship came in 1760, in a farce entitled High Life Below Stairs in which a Miss Kitty poses the question: "Who wrote Shakespeare?" The Duke responds "Ben Jonson." Lady Bab then cries; "Oh, no! Shakespeare was written by one Mr. Finis, for I saw his name at the end of the book." Churchill writes that, while not a very "profound" joke, there "must have been, in the mid-eighteenth century, a certain amount of discussion as to the authenticity of the traditional authorship of Shakespeare, and the substitution of Ben Jonson is significant."[29]

George McMichael and Edward Glenn, summarising the views of doubters, quote passages in some early 18th-century satirical and allegorical works that were later identified by anti-Stratfordians as expressing authorship doubts. In a passage in An Essay Against Too Much Reading (1728) possibly written by Matthew Concanen, Shakespeare is described as "no Scholar, no Grammarian, no Historian, and in all probability cou'd not write English" and someone who uses an historian as a collaborator. The book also says that 'instead of Reading, he [Shakespeare] stuck close to Writing and Study without Book".[30][31] Again, in The Life and Adventures of Common Sense: An Historical Allegory (1769) by Herbert Lawrence, the narrator, "Common Sense", portrays Shakespeare as a thief who stole a commonplace book containing "an infinite variety of Modes and Forms to express all the different sentiments of the human mind" from his father, "Wit" and his half-brother, "Humour". He also stole a magical glass created by "Genius", which allowed him to "penetrate into the deep recesses of the Soul of Man".[32] He used these to write his plays.[30] Thirdly, in a possible allusion to Bacon, The Story of the Learned Pig, By an officer of the Royal Navy (1786) is a tale of a soul that has successively migrated from the body of Romulus into various humans and animals, and is currently residing in The Learned Pig, a famous performing pig at the time that was the subject of much satirical literature. He recalls a previous pre-swinish incarnation in which he was a person called "Pimping Billy", who worked as a horse-holder at the playhouse with Shakespeare and was the real author of 5 of the plays.[30][33]

Shakespearean scholars have seen nothing in these works to suggest genuine doubts about Shakespeare's authorship, since they are all presented as comic fantasies. The scene from High Life Below Stairs simply ridicules the stupidity of the characters, as Samuel Schoenbaum notes, adding that, "the Baconians, who discern in Townley's farce an early manifestation of the anti-Stratfordian creed, have never been remarkable for their sense of humour".[34] Of the three booklets mentioned, the first two explicitly assert that Shakespeare wrote the works, albeit with assistance from a historian in the first, and magical aids in the second.[35] The third does say that "Billy" was the real author of Hamlet, Othello, As You Like It and A Midsummer Night's Dream, but it also claims that he participated in numerous other historical events. Michael Dobson takes Pimping Billy to be a joke about Ben Jonson, since he is said to be the son of a character in Jonson's play Every Man in his Humour.[33]

In the early twentieth century a document—since identified as a forgery—appeared to demonstrate that a Warwickshire cleric, James Wilmot, had been the earliest person to explicitly assert that Shakespeare was not the author of the canon. He was also the first proponent of the Baconian theory, the view that Francis Bacon was the true author of Shakespeare's works. He was supposed to have reached this conclusion in 1781 after searching for documents concerning Shakespeare in Warwickshire. However, there is evidence that the manuscript linking Wilmot with the Baconian thesis (supposedly a pair of lectures given by an acquaintance, James Corton Cowell, in 1805) was probably concocted in the early twentieth century. According to the "Cowell" manuscript, failure to find much evidence of Shakespeare led Wilmot to suggest that Bacon was the author of Shakespeare's works; but concerned that his views would not be taken seriously, he destroyed all evidence of his thinking, confiding his findings only to Cowell.[c]

The rise of bardolatry and authorship doubts

[edit]

During the 1660–1700 period, stage records suggest that Shakespeare, although always a major repertory author, was not as popular on the stage as were the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher. In literary criticism he was nevertheless acknowledged as an untaught genius. In the 18th century, the works of Shakespeare dominated the London stage, and after the Licensing Act 1737, one fourth of the plays performed were by Shakespeare. The plays continued to be heavily cut and adapted, becoming vehicles for star actors such as Spranger Barry and David Garrick, a key figure in Shakespeare's theatrical renaissance, whose Drury Lane theatre was the centre of the Shakespeare mania which swept the nation and promoted Shakespeare as the national playwright. At Garrick's spectacular 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon, he unveiled a statue of Shakespeare and read out a poem culminating with the words "'tis he, 'tis he, / The God of our idolatry".[39]

In contrast to playscripts, which diverged more and more from their originals, the publication of texts developed in the opposite direction. With the invention of textual criticism and an emphasis on fidelity to Shakespeare's original words, Shakespeare criticism and the publication of texts increasingly spoke to readers, rather than to theatre audiences, and Shakespeare's status as a "great writer" shifted. Dryden's sentiments about Shakespeare's matchless genius were echoed without a break by unstinting praise from writers throughout the 18th century. Shakespeare was described as a genius who needed no learning, was deeply original, and unique in creating realistic and individual characters (see Timeline of Shakespeare criticism). The phenomenon continued during the Romantic era, when Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, William Hazlitt, and others all described Shakespeare as a transcendent genius. By the beginning of the 19th century Bardolatry was in full swing and Shakespeare was universally celebrated as an unschooled supreme genius and had been raised to the statute of a secular god and many Victorian writers treated Shakespeare's works as a secular equivalent to the Bible.[6] "That King Shakespeare," the essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1840, "does not he shine, in crowned sovereignty, over us all, as the noblest, gentlest, yet strongest of rallying signs; indestructible".[40]

Debate in the 19th century

[edit]

Uneasiness about the difference between Shakespeare's godlike reputation and the humdrum facts of his biography, earlier expressed in allegorical or satirical works, began to emerge in the 19th century. In 1850, Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed the underlying question in the air about Shakespeare with his confession, "The Egyptian [i.e. mysterious] verdict of the Shakspeare Societies come to mind; that he was a jovial actor and manager. I can not marry this fact to his verse."[42] That the perceived dissonance between the man and his works was a consequence of the deification of Shakespeare was theorized by J. M. Robertson, who wrote that "It is very doubtful whether the Baconian theory would ever have been framed had not the idolatrous Shakespeareans set up a visionary figure of the Master."[43]

At the same time scholars were increasingly becoming aware that many plays were collaborations, and that now-lost plays may have served as models for Shakespeare's published work, such as, for example, the ur-Hamlet, an earlier version of Shakespeare's play of that name. In Benjamin Disraeli's novel Venetia (1837) the character Lord Cadurcis, modelled on Byron,[44] questions whether Shakespeare wrote "half of the plays attributed to him",[45] or even one "whole play"[45] but rather that he was "an inspired adapter for the theatres".[45] A similar view was expressed by an American lawyer and writer, Col. Joseph C. Hart, who in 1848 published The Romance of Yachting, which for the first time asserted explicitly and unequivocally in print that Shakespeare did not write the works bearing his name. Hart claimed that Shakespeare was a "mere factotum of the theatre", a "vulgar and unlettered man" hired to add obscene jokes to the plays of other writers.[46] Hart does not suggest that there was any conspiracy, merely that evidence of the real authors's identities had been lost when the plays were published. Hart asserts that Shakespeare had been "dead for one hundred years and utterly forgotten" when old playscripts formerly owned by him were discovered and published under his name by Nicholas Rowe and Thomas Betterton. He speculates that only The Merry Wives of Windsor was Shakespeare's own work and that Ben Jonson probably wrote Hamlet.[47] In 1852 an anonymous essay in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal also suggested that Shakespeare owned the playscripts, but had employed an unknown poor poet to write them.[48]

Delia Bacon and the first group theory

[edit]In 1853, with help from Emerson, Delia Bacon, an American teacher and writer, travelled to Britain to research her belief that Shakespeare's works were written by a group of dissatisfied politicians (including Sir Walter Raleigh, Edmund Spenser, Lord Buckhurst and the Earl of Oxford), in order to communicate the advanced political and philosophical ideas of Francis Bacon (no relation). She discussed her theories with British scholars and writers. In 1856 she wrote an article in Putnam's Monthly in which she insisted that Shakespeare of Stratford would not have been capable of writing such plays, and that they must have expressed the ideas of an unspecified great thinker.

Candidacy of Sir Francis Bacon

[edit]In September 1856 William Henry Smith wrote a letter which was subsequently published in a pamphlet, Was Lord Bacon the author of Shakespeare's plays?: a letter to Lord Ellesmere (1856), expressing his view that Francis Bacon himself had written the works. In the preface to a subsequent book, Bacon and Shakespeare: An Inquiry Touching Players, Play-Houses, and Play-writers in the Days of Elizabeth (1857), Smith claimed to have been unaware of Delia Bacon's essay and to have held his opinion for nearly 20 years.[49] In 1857 Bacon expanded her ideas in her book, The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspere Unfolded.[50] She argued that Shakespeare's plays were written by a secretive group of playwrights led by Sir Walter Raleigh and inspired by the philosophical genius of Sir Francis Bacon. Later writers such as Ignatius L. Donnelly portrayed Francis Bacon as the sole author. The Baconian movement attracted much attention and caught the public imagination for many years, mostly in America.[51][d] Ignatius Donnelly's claim to have discovered ciphers in the works of Shakespeare revealing Bacon as a "concealed poet" were later discredited by William and Elizebeth Friedman, expert code-breakers, in their book The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined.[53]

The first book by Charlotte Stopes on Shakespearean matters was The Bacon/Shakespeare Question (1888), which examined attitudes on particular details found both in Bacon's works and in those attributed to Shakespeare. Mrs Stopes concluded that there were fundamental differences, arguing that Bacon was not the author. The book met with sufficient success leading to it being revised and re-released the following year under the name The Bacon/Shakespeare Question Answered.[54]

A new twist was added in the writings of Orville Ward Owen and Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who claimed to have uncovered evidence that Francis Bacon was the secret son of Queen Elizabeth, who had been privately married to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. The couple were also the parents of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. This provided a further explanation for Bacon's anonymity. Encoded within his works was a secret history of the Tudor era.[56] Bacon was the true heir to the throne of England, but had been excluded from his rightful place. This tragic life-story was the secret hidden in the plays. This argument was taken up by several other writers, notably C.Y.C. Dawbarn in Uncrowned (1913) and Alfred Dodd in The Personal Poems of Francis Bacon (1931) and many other publications.[57]

The American poet Walt Whitman declared himself agnostic on the issue and refrained from endorsing an alternative candidacy. Voicing his skepticism to Horace Traubel, Whitman remarked, "While I am not yet ready to say Bacon I am decidedly unwilling to say Shaksper. I do not seem to have any patience with the Shaksper argument: it is all gone for me-all up the spout. The Shaksper case is about closed."[58]

In 1891 the archivist James H. Greenstreet identified a pair of 1599 letters by the Jesuit spy George Fenner in which he reported that William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby was "busy penning plays for the common players." Greenstreet proposed Derby as the real hidden author, founding the Derbyite theory.[59] Greenstreet's theory was revived by the American writer Robert Frazer, who argued in The Silent Shakespeare (1915) that the actor William Shakespeare merely commercialised the productions of more elevated authors, sometimes adapting older works. He believed that Derby was the principal figure behind the Shakespeare plays and was the sole author of the sonnets and narrative poems. He concludes that "William Stanley was William Shakespeare".[60]

As early as 1820 it had been suggested that, because of their "habitual resemblance of style", Shakespeare had in fact written the works of the poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe,[61] but it was not until 1895 that this theory was reversed, and Marlowe himself proposed as the most likely author of the Shakespeare canon, with a serious case for this being made by Wilbur G. Zeigler in the foreword and notes to his novel, It Was Marlowe: A Story of the Secret of Three Centuries.[8] He was followed by T. C. Mendenhall who, in February 1902, wrote an article based upon his own stylometric work titled "Did Marlowe write Shakespeare?"[9]

20th-century candidates

[edit]

After Marlowe, the first notable new candidate was Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland. German literary critic Karl Bleibtreu supported the nomination of Rutland as sole author of the canon in 1907, after an earlier critic had suggested that he may have written the comedies.[62] Rutland's candidacy enjoyed a brief flowering, promoted by a number of other authors over the next few years, notably the Belgian Célestin Demblon.[63] Rutland's authorship was defended by the suggestion that the plots of the plays reflected details of his life, an argument that was to become important to claims for candidates proposed in the 20th century. The Rutlandite position was revived by Ilya Gililov in the 21st century.[64]

Starting in 1908, Sir George Greenwood engaged in a series of well-publicised debates with Shakespearean biographer Sir Sidney Lee and author J. M. Robertson. Throughout his numerous books on the authorship question, Greenwood limited himself to arguing against the traditional attribution, without supporting any alternative candidate.[65] Mark Twain, commenting in 1908 on the lack of a literary paper trail linking Shakespeare of Stratford to the works, said, "Many poets die poor, but this is the only one in history that has died THIS poor; the others all left literary remains behind. Also a book. Maybe two."[66] Twain strongly suspected, as a 'Brontosaurian', that Bacon wrote the works.[67] H. L. Mencken wrote a withering review of the work, concluding that it makes sorry reading for those who revered Twain.[68]

In 1918, Professor Abel Lefranc, a renowned authority on François Rabelais, published the first volume of Sous le masque de "William Shakespeare" in which he provided detailed arguments for the claims of the Earl of Derby.[7] Many readers were impressed by Lefranc's arguments and by his undoubted scholarship, and a large international body of literature resulted.[69] Lefranc continued to publish arguments in favour of Derby's candidature throughout his life.

Marlowe re-examined

[edit]

In 1916, on the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare's death, Henry Watterson, the long-time editor of The Courier-Journal, wrote a widely syndicated front-page feature story supporting the case for Christopher Marlowe[10] and, like Zeigler, created a fictional account of how it might have happened. In 1923 Archie Webster published "Was Marlowe the Man?" in The National Review, also arguing that Marlowe wrote the works of Shakespeare, and in particular that the Sonnets were an autobiographical account of his life after 1593, assuming that his recorded death that year must have been faked.[11] None of these shorter pieces received much attention, however, and it was not until Calvin Hoffman wrote his 1955 book, "The Man Who Was Shakespeare"[12] that general awareness of the theory gained any real ground. Marlowe continues to attract supporters, and in 2001, the Australian documentary film maker Michael Rubbo released the TV film Much Ado About Something, which explores the subject in some detail. It has played a significant part in bringing the Marlovian theory to the attention of the greater public.

The Oxford candidacy

[edit]In 1920, John Thomas Looney, an English school-teacher, published "Shakespeare" Identified, proposing a new candidate for the authorship in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. The theory gained several notable advocates, including Sigmund Freud. Some followers of Looney, notably Percy Allen, developed what came to be known as Prince Tudor theory, which adapted the arguments of Owen and Gallup about a hidden child of the queen's and argued that Elizabeth and Oxford had an affair which resulted in the birth of a son, who became the Earl of Southampton. The sonnets told the story of this affair and were addressed to the Earl, covertly revealing that he was the heir to the throne.[70][71] Allen's theories were expanded upon in This Star of England (1952) by Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn Sr.

By the early 20th century, the public had tired of cryptogram-hunting, and the Baconian movement faded, though its remnants remain to this day. The result was increased interest in Derby and Oxford as alternative candidates.[72] In 1921, Greenwood, Looney, Lefranc and others joined together to create the Shakespeare Fellowship, an organisation devoted to promote discussion and debate on the authorship question but endorsing no particular candidate. Since then a great many candidates have been put forward, including Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway, his supposed girlfriend Anne Whateley, and numerous scholars, aristocrats and poets. New candidates are regularly put forward, such as Mary Sidney (proposed in 1931), Edward Dyer (proposed in 1943), William Nugent (proposed in 1978), Henry Neville (proposed in 2005) and Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter (proposed in 2019). Some candidates have been promoted by single authors, others have gathered several published supporters. Sidney in particular has been promoted in several publications in the 21st century, including Robin Williams's Sweet Swan of Avon, in which she is presented as the central figure in the literary circles of the era.[73]

Since the publication of Charlton Ogburn Jr.'s The Mysterious William Shakespeare: the Myth and the Reality in 1984, the Oxfordian theory, boosted in part by the advocacy of several Supreme Court justices, high-profile theatre professionals, and some academics, has become the most popular alternative authorship theory.

Academic views

[edit]In 2007, the New York Times surveyed 265 Shakespeare teachers on the topic. To the question "Do you think there is good reason to question whether William Shakespeare of Stratford is the principal author of the plays and poems in the canon?", 6% answered "yes" and an additional 11% responded "possible", and when asked if they "mention the Shakespeare authorship question in your Shakespeare classes?", 72% answered "yes". When asked what best described their opinion of the Shakespeare authorship question, 61% answered that it was "A theory without convincing evidence" and 32% called the issue "A waste of time and classroom distraction".

In September 2007, the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition sponsored a "Declaration of Reasonable Doubt" to encourage new research into the question of Shakespeare's authorship, which has garnered more than 3,000 signatures, including more than 500 academics.[74] In late 2007, Brunel University of London began offering a one-year MA program on the Shakespeare authorship question (since suspended),[75] and in 2010, Concordia University (Portland, Oregon) opened the Shakespeare Authorship Research Centre.[76] [77]

Non-English candidates

[edit]

Some suggestions do not necessarily imply a secret author, but an alternative life-history for Shakespeare himself. These overlap with or merge into alternative-author models. An example is the claim that he was an Arab whose real name was "Sheikh Zubayr". This was first proposed in the 19th century as a joke by Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq, but developed seriously by Iraqi writer Safa Khulusi in the 1960s.[79] It was later endorsed by Muammar Gaddafi.[80] Such claims for a non-English origin for Shakespeare were linked to the expansion of his influence and popularity globally. Claimants have been detected in other countries, and he has even figured as a "contested heirloom", appropriated to various competing national or ethnic identities.

His Englishness was first disputed in the wake of the Romantic "Shakespeare mania" (Shakespearomanie) that swept Germany, and led to assertions of his Nordic character,[81] and to claims that he was essentially German.[82] However, no alternative German candidate was proposed. Instead Shakespeare of Stratford himself was identified as racially and culturally Germanic. The claim that Shakespeare was German was particularly stressed during World War I, and was later ridiculed in British propaganda. The meme resurfaced in anti-Nazi propaganda later.[83] Nazi views of his Germanic identity were ambivalent. Gustav Plessow's 1937 racial analysis ostensibly demonstrated that "the Nordic element in Shakespeare was in fact predominant, though not quite without alien admixtures: the virtues of his perfect Nordic forehead were somewhat marred by Mediterranean eyes and hair and a chin of doubtful origin."[81]

As early as 1897, George Newcomen had suggested Shakespeare was an Irishman, a certain Patrick O'Toole of Ennis.[84] Thomas Fingal Healy, writing for The American Mercury in 1940, picked up the idea, claiming that many of the plays draw on Irish folklore. Shakespeare was forced to conceal his Irish background because the Irish were considered a "rebel race" by Queen Elizabeth. Healy found numerous references in the text of Hamlet to clothes which, he thought, showed that the Dane was based on a legendary Irish tailor called Howndale.[84] The distinguished County Meath historian Elizabeth Hickey writing under the pen name of Basil Iske, claimed in 1978 that she had identified the Irish Shakespeare as the rebel and adventurer William Nugent. She asserted that there were numerous distinctively Irish idioms in Shakespeare's work.[85]

Sigmund Freud, before adopting the Edward de Vere identification, toyed with the notion that Shakespeare may not have been English, a doubt strengthened in 1908 after he believed he had detected Latin features in the Chandos portrait. On the basis of a suggestion by a Professor Gentilli of Nervi, Freud came to suspect that Shakespeare was of French descent, and his name a corruption of "Jacques Pierre".[86][87][88]

The case for an Italian, either Michelangelo Florio or his son John Florio, as author of Shakespeare's works was initially associated with resurgent Italian nationalism of the Fascist era.[89] Michelangelo Florio was proposed by Santi Paladino in 1927, in the Fascist journal L'Impero. The theory is linked to the argument put forward by other anti-Stratfordians that Shakespeare's work shows an intimate knowledge of Italian culture and geography. John Florio was proposed by Erik Reger, in an article entitled "Der Italiener Shakespeare" contributed to the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung shortly after Paladino's publication in the same year. Paladino claimed that Florio came from a Calvinist family in Sicily. Forced to flee to Protestant England, he created "Shakespeare" by translating his Sicilian mother's surname, Crollalanza, into English.[89] One or both of the Florios have since been promoted by Carlo Villa (1951), Franz Maximilian Saalbach (1954), Martino Iuvara (2002), Lamberto Tassinari (2008) and Roberta Romani (2012).[90][91] Paladino continued to publish on the subject into the 1950s.[90] In his later writings he argued that Michelangelo Florio wrote the works in Italian, and his son John rendered them into English.[92]

Another Italian candidate was proposed by Joseph Martin Feely in a number of books published in the 1930s, however Feely was unable to discover his name. Nevertheless, he was able to deduce from ciphers hidden in the plays that the true author was the illegitimate child of an Italian aristocrat ("sprung basely from noble Italian blood"), and educated in Florence. He then moved to England where he became a tutor in Greek, mathematics, music, and languages, before becoming a playwright.[93] Emilia Lanier's candidacy is also linked to her Italian family background, but involved the additional claim that she was Jewish. Lanier's authorship was proposed by John Hudson in 2007, who identified her as "a Jewish woman of Venetian ancestry", arguing that only a person with her distinctive ethnic background could have written the plays.[94]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Nicholl 2010, p. 4: "The call for an 'open debate' which echoes through Oxfordian websites is probably pointless: there is no common ground of terminology between 'Stratfordians' (as they are reluctantly forced to describe themselves) and anti-Stratfordians."; Rosenbaum 2005: "What particularly disturbed (Stephen Greenblatt) was Mr. Niederkorn’s characterization of the controversy as one between 'Stratfordians' . . and 'anti-Stratfordians'. Mr. Greenblatt objected to this as a tendentious rhetorical trick. Or as he put it in a letter to The Times then: 'The so-called Oxfordians, who push the de Vere theory, have answers, of course—just as the adherents of the Ptolemaic system . . . had answers to Copernicus. It is unaccountable that you refer to those of us who believe that Shakespeare wrote the plays as "Stratfordians," as though there are two equally credible positions'."

- ^ "No one in Shakespeare's lifetime or the first two hundred years after his death expressed the slightest doubt about his authorship."[2]

- ^ The paper was only made public when its contents were published by Allardyce Nicoll in the Times Literary Supplement in 1932. Allardyce Nicoll, "The First Baconian", Times Literary Supplement, February 25, 1932, p. 128. Reply by William Jaggard, March 3, p. 155; response from Nicoll, March 10, p. 17. It was contained in a "thin quarto volume" donated by the widow of Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence (1837–1914) to the University of London in 1929. The manuscript was considered authentic by later Shakespeare scholars, but in 2003 was challenged by (authorship doubter) Daniel Wright based on research by John Rollet, who asserted that no records exist of Cowell, nor of the Ipswich Philosophic Society at this date. Edwin Durning-Lawrence was a leading supporter of Bacon's candidacy as author of the Shakespeare canon, having written Bacon is Shake-Speare (1910) and The Shakespeare Myth (1912). Wright and Rollet suggested that the manuscript may have been forged by a Bacon supporter and added to the Durning-Lawrence archive in the 1920s.[36] James S. Shapiro has since provided linguistic evidence of forgery as well.[37][38]

- ^ 'By far the greatest number of contributions, on both sides of the question, come from Americans; in an 1884 bibliography containing 255 titles, almost two-thirds were written by Americans. In 1895 the Danish critic Georg Brandes fulminated against the "troop of half-educated people" who believed that Shakespeare did not write the plays, and bemoaned the fate of the profession. "Literary criticism," which "must be handled carefully and only by those who had a vocation for it," had clearly fallen into the hand of "raw Americans and fanatical women".'[52]

References

[edit]- ^ Edmondson & Wells 2013, p. 2.

- ^ a b Bate 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, pp. 16, 20.

- ^ Price 2001, pp. 224–26.

- ^ Friedman & Friedman 1957, pp. 1–4, cited in McMichael & Glenn 1962, p. 56;Wadsworth 1958, p. 10

- ^ a b Sawyer 2003, p. 113.

- ^ a b Michell 1996, p. 191.

- ^ a b Zeigler 1895.

- ^ a b Mendenhall 1902.

- ^ a b Watterson 1916.

- ^ a b Webster 1923.

- ^ a b Hoffman 1955.

- ^ Gibson 2005, pp. 48, 72, 124.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, pp. 430–40.

- ^ Gibson 2005, pp. 59–65.

- ^ Michell 1996, pp. 126–29.

- ^ a b c McCrea 2005, pp. 21, 170–71, 217.

- ^ A Davenport, The Poems of Joseph Hall, Liverpool University Press, 1949.

- ^ Barrell, Charles Wisner. “Oxford vs. Other ‘Claimants’ of the Edwards Shakespearean Honors, 1593” Archived 2012-03-18 at the Wayback Machine; The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (Summer 1948)

- ^ Stritmatter 2006.

- ^ James & Rubinstein 2006, p. 337.

- ^ Shell 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Robert Detobel, K.C. Ligon, "Francis Meres and the Earl of Oxford", Brief Chronicles: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Authorship Studies, 1: 1, 2009, pp. 97–108.

- ^ Peter Farey, "The Stratford Monument: A Riddle and Its Solution", Journal of the Open University Shakespeare Society, 12: 3, 2001, pp. 62-74.

- ^ Price 2001, pp. 193–94.

- ^ Price 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Marjorie B. Garber, Profiling Shakespeare, Taylor & Francis, 24 Mar 2008, p. 221.

- ^ Edwin Durning-Lawrence, Bacon Is Shake-Speare, John McBride Co., New York, 1910, pp. 23, 79–80.

- ^ a b Churchill, Shakespeare and His Betters, 1959, Indiana University Press, pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b c McMichael & Glenn 1962, p. 56.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, p. 10.

- ^ Herbert Lawrence, The life and adventures of common sense: an historical allegory, Montagu Lawrence, 1769, pp. 147-48.

- ^ a b Dobson 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 395.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 396.

- ^ James & Rubinstein 2006, p. 313.

- ^ Shapiro 2010b, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Shapiro 2010a, pp. 1–2, 11–14.

- ^ Dobson 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1840). "On Heroes, Hero Worship & the Heroic in History". Quoted in Smith 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Nelson, Paul A. "Walt Whitman on Shakespeare. Reprinted from The Shakespeare Oxford Society Newsletter, Fall 1992: Volume 28, 4A.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, p. 19.

- ^ McCrea 2005, p. 220.

- ^ Ridley 1995, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Disraeli 1837, p. 231.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Joseph C. Hart,The romance of yachting: voyage the first, Harper, New York, 1848, "the ancient lethe", unpaginated.

- ^ "Who Wrote Shakespeare", Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, August, 1852.

- ^ Lang 2004, pp. 314–15.

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, pp. 408–09.

- ^ Garber 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Friedman & Friedman 1957.

- ^ Stephanie Green (2013). The Public Lives of Charlotte and Marie Stopes. London: Pickering & Chatto. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Daily Telegraph 2009.

- ^ Hackett 2009, pp. 157–60.

- ^ Dobson & Watson 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Traubel, Bradley & Traubel 1915, p. 239.

- ^ Coward 1983, p. 64 citing Greenstreet, James. "A Hitherto Unknown Noble Writer of Elizabethan Comedies", The Genealogist, New Series, 1891, Vol. 7

- ^ Frazer 1915, p. 210.

- ^ The Monthly Review Or Literary Journal, Vol XCIII, 1820

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, pp. 106–10.

- ^ Campbell 1966, pp. 730–31.

- ^ Ilya Gililov, The Shakespeare Game, Or, The Mystery of the Great Phoenix, Algora Publishing, 2003.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 427.

- ^ Mark Twain "Is Shakespeare Dead?"

- ^ Garber 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Bloom 2008, pp. 199–20.

- ^ Michell 1996, p. 197.

- ^ Shapiro 2010a, pp. 196–210.

- ^ Sword 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 431.

- ^ Warren Hope, Kim R. Holston, The Shakespeare controversy: an analysis of the authorship theories, McFarland, 2009, p. 129

- ^ http://doubtaboutwill.org/signatories/field

- ^ "Leading actors applaud first MA in Shakespeare authorship studies" Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, 10 September 2007, Brunel University London News.

- ^ Edmondson & Wells 2013, p. 226.

- ^ "Support the Shakespeare Authorship Research Centre at Concordia University", Concordia University Web site.

- ^ Abdulla Al-Dabbagh, Shakespeare, the Orient, and the Critics, Peter Lang, 2010, p. 1

- ^ Eric Ormsby, "Shadow Language", New Criterion, Vol. 21, Issue: 8, April 2003.

- ^ "Libya Accuses British of Chauvinism on Shakespeare Origins". Associated Press.

- ^ a b Ahrens 1989, p. 101.

- ^ Leerssen 2008, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Burt 2008, pp. 437–55.

- ^ a b Wadsworth 1958, p. 132.

- ^ Cook 2013, p. 248.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 441.

- ^ Jones 1961, p. 18.

- ^ Shapiro 2010a, p. 185.

- ^ a b Marrapodi 2007, p. 102.

- ^ a b Bate 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Cook 2013, p. 247.

- ^ Campbell 1966, p. 234.

- ^ Friedman & Friedman 1957, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Amini 2008, p. 1.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ahrens, Rüdiger (1989). "The Critical Reception of : Shakespeare's Tragedies in Twentieth Century Germany". In Dotterer, Ronald (ed.). Shakespeare: Text, Subtext, and Context. Associated University Presses Susquehanna University Studies, Vol 13. ISBN 9780941664929. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Amini, Daniela (28 February 2008), "Kosher Bard", New Jersey Jewish News, archived from the original on February 8, 2013

- "Stamp-sized Elizabeth I miniatures to fetch £80,000". Daily Telegraph. 17 November 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- Bate, Jonathan (1998). The Genius of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512823-9. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2008). Mark Twain. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-134-5.

- Burt, Richard (2008). "Sshockspeare: (Nazi) Shakespeare goes Heil-lywood". In Hodgdon, Barbara; Worthen, W.B. (eds.). A Companion to Shakespeare and Performance. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-405-15023-1. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Campbell, Oscar James, ed. (1966). A Shakespeare Encyclopedia. London: Methuen.

- Cook, Hardy (2013). "A selected reading list". In Edmondson, Paul; Wells, Stanley (eds.). Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780941664929. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Coward, Barry (1983). The Stanleys, Lords Stanley, and Earls of Derby, 1385–1672: the origins, wealth, and power of a landowning family. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1338-6. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Disraeli, Benjamin (1837). Venetia. Vol. 3. London: H. Colburn. hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t7xk90r83.

- Dobson, Michael (1992). The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660–1769. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811233-4. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

editions:2BCCq_0w8sAC.

- Dobson, Michael (2003). "Shakespeare as a Joke: The English Comic Tradition, Midsummer Night's Dream and Amateur Performance". In Holland, Peter (ed.). Shakespeare and comedy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 117–25. ISBN 978-0-521-82727-0.

- Dobson, Michael; Watson, Nicola J. (2004). England's Elizabeth: An Afterlife in Fame and Fantasy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926919-8.

- Edmondson, Paul; Wells, Stanley, eds. (2013). Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60328-8.

- Frazer, Robert (1915). The Silent Shakespeare. WJ Campbell, Philadelphia.

- Friedman, William F.; Friedman, Elizebeth S. (1957). The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05040-1.

- Garber, Marjorie B (2008). Profiling Shakespeare. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96445-6. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Gibson, H. N. (2005) [1962]. The Shakespeare Claimants. Routledge Library Editions — Shakespeare. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35290-1. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Hackett, Helen (2009). Shakespeare and Elizabeth: the meeting of two myths. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12806-1.

- Hoffman, Calvin (1955). The Man Who Was Shakespeare. London: Max Parrish.

- James, Brenda; Rubinstein, William D. (2006). The truth will out: unmasking the real Shakespeare. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1-4058-4086-6.

- Jones, Ernest (1961). The life and work of Sigmund Freud vol. 1. Basic Books.

- Lang, Andrew (2004) [1903]. The Valet's Tragedy and Other Studies. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-8897-6. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Leerssen, Joep (2008). "Making Shakespeare National". In Delabastita, Dirk (ed.). The Valet's Tragedy and Other Studies. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-874-13004-1. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Marrapodi, Michele (2007). Italian Culture in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754655046. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- McCrea, Scott (2005). The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98527-1. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- McMichael, George L.; Glenn, Edgar M. (1962). Shakespeare and His Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. Odyssey Press. OCLC 2113359.

- Mendenhall, Thomas C. (February 1902). "Did Marlowe write Shakespeare?". Current Literature. New York: Current Literature Publishing Co.

- Michell, John (1996). Who wrote Shakespeare?. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01700-5. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Nicholl, Charles (21 April 2010). "Yes, Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare". Times Literary Supplement. No. 5586. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 20 December 2010.[dead link]

- Price, Diana (2001). Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31202-1.

- Ridley, Jane (1995). The Young Disraeli. Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-85619-736-6. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Rosenbaum, Ron (18 September 2005). "The Shakespeare Code: Is Times Guy Kind Of Bard 'Creationist'?". The New York Observer. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Sawyer, Robert (2003). Victorian Appropriations of Shakespeare. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3970-2.

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1991). Shakespeare's Lives (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818618-2.

- Shapiro, James (2010a). Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23576-6.

- Shapiro, James (26 March 2010b). "Forgery on Forgery". Times Literary Supplement. No. 5581. pp. 14–15.

- Shell, Alison (2006). "Why Didn't Shakespeare Write Religious Verse?". In Kozuka, Takashi; Mulryne, J.R. (eds.). Shakespeare Marlowe Jonson: New Directions in Biography. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5442-7. Retrieved 12 Feb 2014.

- Smith, Emma (2004). Shakespeare's Tragedies. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22010-7. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Stritmatter, Roger (2006). "Tilting Under Frieries": Narcissus (1595) and the Affair at Blackfriars". Cahiers Élisabéthains. 70 (3). University of Chicago Press: 37–39. doi:10.7227/ce.70.1.6. S2CID 191403664.

- Sword, Helen (1999). "Modernist Hauntology: James Joyce, Hester Dowden, and Shakespeare's Ghost". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 41 (2). University of Chicago Press.

- Traubel, Horace; Bradley, Sculley; Traubel, Gertrude (1915). With Walt Whitman in Camden. Vol. 1. M.Kennerly.

- Wadsworth, Frank (1958). The Poacher from Stratford: A Partial Account of the Controversy over the Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01311-7. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Watterson, Henry (1916). "The Shakespeare Mystery". The Pittsburgh Gazette Times. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Webster, Archie (1923). "Was Marlowe the Man?". The National Review. 82: 81–86. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Zeigler, Wilbur Gleason (1895). It was Marlowe: a Story of the Secret of Three Centuries. Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry & Co. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

External links

[edit]- Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakespeare's Plays?: A Letter to Lord Ellesmere (1856) by William Henry Smith at Goggle Books.

- The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspere Unfolded (1857) by Delia Bacon, preface by Nathanial Hawthorne, at Google Books.

- Bacon and Shakespeare: An Inquiry Touching Players, Playhouses, and Play-writers in the Days of Elizabeth (1857) by William Henry Smith at Google Books.