History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795)

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 15,500 words. (May 2021) |

| History of Poland |

|---|

|

| History of Lithuania |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

|

|

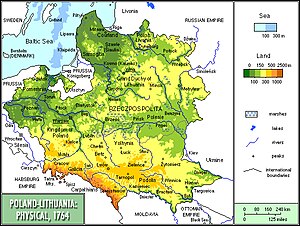

The History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795) is concerned with the final decades of existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The period, during which the declining state pursued wide-ranging reforms and was subjected to three partitions by the neighboring powers, coincides with the election and reign of the federation's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski.[1]

During the later part of the 18th century, the Commonwealth attempted fundamental internal reforms. The reform activity provoked hostile reaction and eventually military response on the part of the surrounding states. The second half of the century brought improved economy and significant growth of the population. The most populous capital city of Warsaw replaced Danzig (Gdańsk) as the leading trade center, and the role of the more prosperous urban strata was increasing. The last decades of the independent Commonwealth existence were characterized by intense reform movements and far-reaching progress in the areas of education, intellectual life, arts and sciences, and especially toward the end of the period, evolution of the social and political system.[1]

The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław August Poniatowski, a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to a major magnate faction, but hand-picked and imposed by Empress Catherine II of Russia, who expected Poniatowski to be her obedient follower. The King accordingly spent his reign torn between his desire to implement reforms necessary to save the state, and his perceived necessity of remaining in subordinate relationship with his Russian sponsors. The Bar Confederation of 1768 was a szlachta rebellion directed against Russia and the Polish king, fought to preserve Poland's independence and in support of szlachta's traditional causes. It was brought under control and followed in 1772 by the First Partition of the Commonwealth, a permanent encroachment on the outer Commonwealth provinces by the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Habsburg Austria. The "Partition Sejm" under duress "ratified" the partition fait accompli. In 1773 the Sejm established the Commission of National Education, a pioneering in Europe government education authority.[2]

The long-lasting sejm convened by Stanisław August in 1788 is known as the Great, or Four-Year Sejm. The Sejm's landmark achievement was the passing of the May 3 Constitution, the first in modern Europe singular pronouncement of a supreme law of the state. The reformist but moderate document, accused by detractors of French Revolution sympathies, soon generated strong opposition coming from the Commonwealth's upper nobility conservative circles and Catherine II, determined to prevent a rebirth of a strong Commonwealth. The nobility's Targowica Confederation appealed to the Empress for help and in May 1792 the Russian army entered the territory of the Commonwealth. The defensive war fought by the forces of the Commonwealth ended when the King, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated by joining the Targowica Confederation. The Confederation took over the government, but Russia and Prussia in 1793 arranged for and executed the Second Partition of the Commonwealth, which left the country with critically reduced territory, practically incapable of independent existence.[3]

The radicalized by the recent events reformers, in the still nominally Commonwealth area and in exile, were soon working on national insurrection preparations. Tadeusz Kościuszko was chosen as its leader; the popular general came from abroad and on March 24, 1794 in Cracow (Kraków) declared a national uprising under his command. Kościuszko emancipated and enrolled in his army many peasants, but the hard-fought insurrection, strongly supported also by urban plebeian masses, proved incapable of generating the necessary foreign collaboration and aid. It ended suppressed by the forces of Russia and Prussia, with Warsaw captured in November. The third and final partition of the Commonwealth was undertaken again by all three partitioning powers, and in 1795 the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth effectively ceased to exist.[3]

Economic transformations and beginnings of capitalist development

[edit]Revitalized economy, serfdom, agricultural rent and hired labor

[edit]

Commencing primarily in the second half of the 18th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth experienced economic transformations, which culminated in the formation of a capitalist system a century later. The more advanced West European countries were a source of examples of economic progress and formulated the ideology of Enlightenment, which provided theoretical foundations for the Polish undertakings. Industrial development, population growth and frequent warfare in the West increased the demand for agricultural products, which resulted in improved, for the agriculture-dominated Commonwealth, market situation: from the 1760s prices kept growing for farm and forest products imported from the East. The Commonwealth's grain exports reached again the high levels of the early 17th century. The internal market for produce was making gradual progress as well, because of increasing population of towns and because of urban people abandoning the agricultural labor market, which many of them had joined in times of high economic stress. Agricultural producers were able again to invest in their trade.[4]

Despite these favorable conditions, the degree of the economic change and whether it had reached a turning point is a matter of dispute. The Commonwealth started from a very low level of economic activity early in the 18th century and its rate of growth remained less than half of that of highly developed countries, such as Great Britain or France. The relative economic backwardness had therefore remained and was one of the underlying reasons for the political and military weakness of the state.[4]

Because of conservative resistance to changes, despite a multitude of self-help books available, agricultural economy and agrarian social relations were changing slowly. Potato cultivation was becoming more common first in Silesia and Pomerania. More typically agricultural improvements were being introduced in the western provinces of the Commonwealth, Greater Poland and Pomerelia (Gdańsk Pomerania), but overall grain yields had not yet reached the productivity of the Renaissance economy.[4]

Enlightenment political and economic publicists had become preoccupied with promoting fundamental alteration of social aspects of agricultural production, in particular with serfdom and the necessity of its reform. Insufficient productivity and quality of output of folwark enterprises was increasingly forcing their szlachta operators to supplant or supplement the overburdened serf labor with agricultural hired work force and rent of farmland.[4]

A pool of agricultural laborers, the "loose" people, often subjected to restrictions, were in demand and enticed by published wage tariffs in times of labor shortages. Feudal rent offered enterprising peasants more independence and ability to get ahead, if fees were reasonable. Such alternative arrangements were practiced in a minority of landed estates, most often in the western provinces of the Commonwealth. Oppressive serfdom had remained the dominant form of agricultural production throughout the vast ranges of Poland and Lithuania.[4]

Manufacturing industry and trade

[edit]

The level of economic prosperity in the Commonwealth was largely determined by its agricultural production, but for the fundamental transformation that the country experienced in the second half of the 18th century, the changes taking place in the cities and within the industrial sphere were of crucial importance. At the outset manufacturing and crafts were underdeveloped in comparison with Prussia, Austria and Russia. The hurried efforts to close the half-century delay and industrialization gap that took place especially during the last three decades of the Commonwealth's existence, were only partially successful.[5]

The industrialization process, initiated by landed magnates in the first half of the 18th century, intensified during its second half, when burgher entrepreneurship also became a significant component. Important for the development of manufacturing, mining and industrial financing was the leadership of King Stanisław August Poniatowski, from the early years of his reign. Production workshops were most highly developed in the cities of Greater Poland, in Danzig and Pomerelia, Warsaw, Cracow area and some magnate estates in the east. Of the heavy industries, iron production and processing had become most significant, especially in the Old-Polish Industrial Region. The second half of the 18th century brought also heavy industry (metallurgy and mining) to the border region of Upper Silesia.[5]

The stronger position of urban entrepreneurs was also a result of the revitalized trade. Under the King's leadership, steps were taken that led to the abolishment of nobility's monopoly on various trade activities, which made capital concentration in the hands of burgher merchants feasible. The Commonwealth was, however, being subjected to discriminatory trade practices (such as high custom duties, tariffs and fees) imposed by Prussia, Austria and Russia, the Commonwealth's stronger neighbors. Paved roads and inland waterways were constructed or improved by state authorities to facilitate the increased trade. Burgher dominated investment financing and general lending, previously concentrated in Danzig, was now done mainly in Warsaw and also in Poznań. The huge fortune accumulated by the banker Piotr Tepper, who came from a non-noble family, was an indication of changing times.[6]

The Commonwealth's balance of trade was negative until the 1780s. The decreased role of Danzig was in part due to the Prussian harassment of the city. Prussian policies also weakened the previously vital exchanges between Silesia and the Commonwealth. Warsaw, the new great commercial center, was crucial for the considerably intensified internal trade. There were also regional trade centers such as Cracow, which served western Lesser Poland and eastern Upper Silesia. The First Partition lessened trade contacts with southern Lesser Poland and Pomerania, incorporated into Austria and Prussia.[6]

Social evolution and early formation of a modern nation

[edit]Changing population patterns during the partitions period; peasantry

[edit]

Early social transformations of the multinational, nobility-dominated Commonwealth population were taking place during the period of the three partitions. To varying degrees they affected all the main strata of the society: peasants, burghers and nobility. The ethnic composition of the Commonwealth was changing with the reduced territory.[7]

The population, estimated at no more than seven million at the end of the Great Northern War, acquired a few additional millions by the time of the First Partition. Western Poland (Kraków and Poznań regions) was much more densely populated than the vast areas in the east. After the Second Partition, the much reduced territory (from 730,000;km2 in 1772 to 200,000;km2 in 1793) contained only 4 million inhabitants. Peasants constituted ¾ of the pre-partitions population, the growing urban strata 17-20%, and the nobility with clergy 8-10%. The population before the First Partition was ⅔ ethnically Polish or Polonized, with the minorities distributed primarily among the non-noble classes.[7]

There were compact concentrations of ethnically Polish settlement west and north of the pre-1772 Commonwealth borders: most of Upper Silesia, parts of Lower Silesia up to Breslau region, Pomerania up to Słupsk and Miastko at the western edge, and parts of southern East Prussia. Numerous in the western and northern Commonwealth Germans constituted a minority there, except for Żuławy and northern Warmia, where they predominated. The Jews, who in many respects constituted a separate estate, were scattered throughout the country and may have had totaled 750,000, of which ⅔ lived in the cities, where their merchants and tradesmen were economically very active. The first partition reduced the proportion of ethnically Polish population to just over 50% of the Commonwealth's total; half of all Poles now lived in Prussia and Austria. Prussian and Austrian authorities introduced Germanization policies in ethnically contested areas before and during the Partitions, which supported settler colonization and restrictions on the use of the Polish language, beginning with Frederick II, Maria Theresa and Joseph II.[7]

by Michał Stachowicz

The state of the peasantry and the issue of improving their lot became one of the leading interests and preoccupations of reformist publicists, chief among them the King. The sejm of 1768 barred feudal lords from imposing the death penalty on their serf subjects, but an attempt to regulate peasants' rights further in the 1780 Zamoyski Code was unsuccessful. Only in 1791 the May 3 Constitution generally took the peasantry under the protection of the law. A more decisive, but short-lived effort to advance the rights of the peasants was the Proclamation of Połaniec promulgated by Tadeusz Kościuszko in 1794, before the demise of the Polish-Lithuanian state. After the first partitions peasants enjoyed limited legal rights under the Prussian jurisdiction, but more meaningful protection and implemented reforms in Austria.[8]

In the Commonwealth, ca. 64% of the peasants lived and worked within the estates of private feudal lords, where conditions differed considerably. The 19% in the royal domains and 17% on Church lands had experienced more systematic improvements in several aspects of their situation. The second half of the 18th century brought more intense stratification of the peasant class, from an increase in the numbers of the extremely pauperized element, to the evolving establishment of affluent peasant groups. The educational level of the rural serf population was improving very slowly, despite the efforts of the Commission of National Education. In times of the existential threat, the idea of national self-defense was met with some peasant response already during the Confederation of Bar, and to a much greater extent at the time of the Kościuszko Uprising.[8]

Burghers and nobles

[edit]

As in many other European countries, the Enlightenment in the Polish-Lithuanian state was a period of great advancement of the burgher class, the upper ranks of which consisted of urban business and professional people, whose economic position was growing stronger and who sought corresponding expansion of political standing and influence. In the middle of the 18th century, the towns and their inhabitants were still in miserable shape, especially in Lithuania. In Poznań Voivodeship (western Poland) urban people constituted ca. 30% of the population, in the eastern provinces below 10%. Danzig, the largest city, fell below 50,000 residents, Warsaw counted less than 30,000. Because of the state protection and revitalized economy, the situation improved during the last decades of the Commonwealth's existence, with Warsaw exceeding 100,000 around 1790; other cities grew more slowly, e.g. Cracow and Poznań reached 20,000 residents each.[9]

During the convocation sejm of 1764, nobility-staffed commissions of good order (boni ordinis) were established. They took some measures aimed at improving urban economics, but their record was mixed and it was not until the Great Sejm era that significant reforms were implemented. From 1775 nobles were no longer barred from practicing the "urban professions". In 1791 burghers of royal cities were given the right to purchase rural property, granted court privileges and access to state offices and the sejm, while szlachta members had their prohibition from holding offices in town governments removed. The urban self-governing institutions were allowed to proceed and develop without interference and were placed under legal protection. The burgher estate had now found itself in a situation favorable in comparison with that of their brethren in Silesia, or in the strictly government-controlled areas appropriated by Prussia after the First Partition, which were also subjected to German colonizing activity at the expense of Polish urban people. The Austrian partition towns experienced lack of significant economic progress.[9]

The early capitalist development brought new elements of social stratification in the cities, including the emergent during the last decade of independence intelligentsia, the banker, manufacturing and trade elites, and the fast-growing plebeian propertyless groups, the nascent proletariat. The laws and reforms of 1764, 1791 and 1793 granted privileges primarily to the propertied and literate urban establishments.[9]

The economically and politically advancing burger class was becoming increasingly important in the cultural life of the Commonwealth, beginning with the German culture-inspired intellectual activity at Danzig and Thorn around the middle of the 18th century, and culminating with wealthy Warsaw townspeople of the final years of the Republic, who built urban palaces and patronized cultural endeavors. The scientist and writer Stanisław Staszic, a leading figure in the Polish Enlightenment, was the most prominent of the non-noble intellectuals of the period. The urban intelligentsia, crucial in the dissemination of the Enlightenment ideology, originated both from impoverished szlachta and from urban families; some of the strongest supporters of the national reform movement and leaders of the Kościuszko Uprising's left wing originated from that group. Many burgher sons attended leading educational institutions in the Commonwealth and abroad. Radical ideas and currents were readily assimilated by the politically very active elements of Warsaw's lower classes. Members of this group massively supported reformist postulates of the Great Sejm, promoted the French Revolution ideals, helped distribute political literature, and were the faction that matured and became indispensable during the Insurrection.[9]

The majority of the nobility (szlachta) wanted to preserve its privileged position, opposed reforms during the early years of King Stanisław August and opposed the Zamoyski Code (proposed in 1776, rejected in 1780). In their final act of obstruction many nobles joined the anti-reform Targowica Confederation in 1792. The leading magnate class, rich, cosmopolitan and educated, became worlds apart from the regular gentry. Their estates in many cases became divided by the partitions and many magnates willingly served foreign interests, although there was a reformist minority that included political activists such as Andrzej Zamoyski and Ignacy Potocki. The middle nobility was more negatively (politically and economically) affected by the First Partition in areas under Prussian and Austrian control and suffered heavy losses during and after the Bar Confederation revolt and uprising. A great majority of older gentry and of those in the more distant regions of the country followed the traditional sarmatism ways and style, while many of the younger and in closer contact with the Warsaw court circles were increasingly inspired by foreign patterns, especially the French fashion, and followed the often utopian Enlightenment trends.[10]

After the First Partition, out of the total of 700,000 nobles in the Commonwealth, a majority (400,000) belonged to the diverse petty nobility stratum. Members of this group possessed little or no property and were rapidly becoming degraded, because under the changing political and social circumstances the work they had traditionally provided for the wealthy (service in private magnate armies, staffing local legislative assemblies, servant duties in manorial estates etc.) were no longer in high demand. The petty gentry clung to nominal szlachta privileges for as long as possible, but they were losing their status and were often forced to become hired laborers or to move to cities. The Great Sejm in 1791 conditioned participation in local assemblies (sejmiks) on rural property minimum yearly income.[10]

In some measure the society was becoming more egalitarian, as new statutes made it easier for upper class burgers to gain the nobility status. From now on the social status would partially, but increasingly, depend on wealth. In the second half of the 18th century, the growing Freemasonry movement, which included most prominent personalities of the era and was not limited to nobles, was an important factor in promoting egalitarian ways of thinking. A modern concept of a nation, as a community of all social classes, was beginning to take hold even among szlachta ideologists.[10]

Intellectual breakthrough and flowering of the arts

[edit]Commission of National Education, educational renewal and progress in science

[edit]

The fundamental educational reform, aimed at broad segments of society, aspired to produce citizens that were enlightened and engaged in public matters, as well as prepared in practical subjects. It contributed greatly to both the changes in general mentality and intellectual achievement of the Polish Enlightenment, with the Commonwealth becoming one of the more active centers of the European culture again. With the existence of the Polish statehood increasingly threatened, education was seen as the way to alter the prevailing mentality of the ruling szlachta class, by imparting a sense of civic duties and enabling them to undertake the necessary reforms.[11]

The first significant reforms of the Jesuit and Piarist schools had already been taking place since the 1740s. Before the First Partition, there were about 104 church-run colleges, ten academic and the rest at the secondary level; nationwide 30 to 35 thousand students attended classes. But the position of the Church was getting weaker, as some segments of society were becoming influenced by the French Enlightenment ideology. The situation was ripe for a state takeover and laicization of schooling, which reflected the prevailing at that time European trends.[11]

The first lay school in Poland, the "School of Knighthood" or the Nobles' Academy of the Corps of Cadets, was established in 1765, soon after Stanisław August's ascent to power. It served primarily the educational needs of the military, was led by the enlightened magnate Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, and produced a number of future military leaders, including Tadeusz Kościuszko.[11]

The general and fundamental educational reform became possible after the Suppression of the Jesuits, who at that time operated a majority of colleges. In 1773 the sejm established, in order to conduct the reform, the Commission of National Education; the Commission was authorized to take over the Jesuit schools, possessions and funds. Among the Commission's members were Andrzej Zamoyski, Ignacy Potocki, bishops Michał Poniatowski and Ignacy Massalski; among its collaborators were educators, including Grzegorz Piramowicz and Hugo Kołłątaj. The Education Commission reformed all aspects and levels of education, from elementary to higher, and it imposed new laicized teaching programs.[11]

Secondary education was supervised by the two major universities, or "main schools", the Academy of Kraków (Cracow) and the Academy of Wilno (Vilnius), both of which were at that time in process of undergoing comprehensive reforms. In Cracow the reform was directed by Kołłątaj, who expanded several departments, especially in the fields of mathematics and the physical sciences, stressed practical applications of academic subjects and introduced the Polish language as the main teaching medium. The "Main School of the Crown" had become, after a long break, a creative scientific center. Effective reforms in Vilnius were accomplished by the outstanding mathematician, Marcin Poczobutt-Odlanicki. The subordinate formerly Jesuit secondary schools were still staffed mainly by teachers from the dissolved order, who generally cooperated with the new lay rules.[11]

Many other schools were directly under the guidance of the Education Commission, whose approved teaching programs emphasized the exact sciences and the national language, history and geography; Latin became restricted and theology was eliminated. "Moral science", aimed at producing responsible citizens, was no longer Catholic religion-based. There were also numerous parish schools, which were not a part of the Commission's official domain, but remained substantially influenced by its work. The Society for Elementary Books, established in 1775, produced 27 modern, mainly secondary education textbooks.[11]

Among the peasant population, the educational progress was still meager. There were ca. 1600 parish schools in 1772, which constituted no more than half of their former number at around the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. More rural schools were established during the Great Sejm era and more girls were enrolled at that time.[11]

The activities of the Commission of National Education resulted in the greatest cultural achievement of the Polish Enlightenment. The educational reforms were vigorously criticized by the conservatives, but the new policies had been successfully defended and remained in force for the duration of the Commonwealth's existence. The Polish-Lithuanian state found itself among the leading European countries regarding the educational organization and quality at the academic and secondary levels; the Commission deeply influenced the prevailing social attitudes of not only its own time, but also well into the 19th century.[11]

There was progress in the area of education in the lands appropriated by Prussia and Austria after the First Partition too. General education was becoming more universally available for the non-noble classes (required of all in Prussia), but the knowledge of German was necessary for the attainment of more than the most basic educational level.[11]

Rationalism and empiricism based science was breaking its dependence on religion, seeking deeper understanding of nature and society. The aim was to scientifically rebuild the society and facilitate exploitation of natural resources through knowledge, which gave strong emphasis also to applied branches of scientific disciplines. Modern scientific notions had been actively developed in Western Europe since the second half of the 17th century, when the Commonwealth was entering its period of backwardness; the current state of knowledge therefore had to be assimilated in the Commonwealth and utilized for local needs in the second half of the 18th century.[12]

State of the art research in astronomy was conducted by Marcin Poczobutt in Vilnius and Jan Śniadecki in Cracow. The mathematicians included the above two researchers and Michał Hube of Thorn. Jan Jaśkiewicz and Józef Osiński were chemists interested also in technical and industrial applications.[12]

Outstanding among the naturalists was Jan Krzysztof Kluk, who researched and described the flora and fauna of Poland and applied his knowledge to agriculture. Cartography and the compilation of maps of the Commonwealth was a major project with military applications and was directed by the King. Karol de Perthées completed only maps of the western part of the country. Jan Potocki traveled widely and left outstanding written accounts of his adventures.[13] Medical knowledge developed mainly at the two universities, where its organizational structures underwent modernization and reform; the major figures were Andrzej Badurski and Rafał Czerniakowski in Cracow.[12]

Antoni Popławski and Hieronim Stroynowski were economists and adherents of physiocracy. The leading intellectual personalities of the period, Hugo Kołłątaj and Stanisław Staszic, subscribed to physiocratic views as well, but also favored state protectionism according to the rules of mercantilism and cameralism. The state was supposed to protect the peasant as the creator of agricultural wealth and help in the development of industry and trade.[12]

Modern history and historiography developed through the work of Feliks Łojko-Rędziejowski, who pioneered the use of statistics, and especially Bishop Adam Naruszewicz. Naruszewicz completed his History of the Polish Nation only to 1386, but also left a collection of highly valuable for historical research source materials and dealt critically with the more recent destructive tendencies in szlachta's politics.[12]

The Enlightenment contribution of Polish science was more modest than that of the Renaissance era, but the common efforts to broaden and popularize the appeal of science and knowledge signified their new social role. There were many textbooks, translations, popular outlines and periodicals, The Historical-Political Diary of Piotr Świtkowski of Warsaw being a prominent example of the last category.[12]

Literature and the arts of the Enlightenment, Rococo and Classicism

[edit]

The Polish literature of the Enlightenment had a primarily didactic character. The works of its main current were classicistic in form and rationalistic in social outlook. There were many sharp polemical exchanges, for which the satire form was frequently utilized. This genre was practiced by Franciszek Bohomolec and Adam Naruszewicz, and in its most highly developed form by Bishop Ignacy Krasicki. Krasicki, dubbed the "Prince of the Poets", wrote also the early Polish novels The Adventures of Nicholas the Experienced and Lord Steward, both instructive in nature. He was a major literary figure of the period and a member of the inner circle of the royal court of Stanisław August Poniatowski. Krasicki's satires Monachomachia and Antymonachomachia ridiculed the mentality and attitudes of Catholic monks. Another poet from the King's circle was Stanisław Trembecki, noted also for his panegyrics.[14]

Bohomolec was a longtime editor of the periodical Monitor, which criticized the social and political relations existing in the Commonwealth and promoted citizenship values and virtues. Because of the dominance of the noble class in Polish society and its culture, it became apparent to the reformers that a literary model citizen they were creating, first just by trying to import the West European patterns, under the Polish conditions had to assume the form of an "enlightened Sarmatian". The idea of a modern, progressive nobleman was explored by Krasicki in his works and had reached its full fruition in the era of the Great Sejm.[14]

Much of the intellectual life was centered around the royal court. The leading writers, artists and scientists participated in the Thursday Dinners at the Royal Castle in Warsaw. The Dinners were the forum provided by the King, a generous sponsor of the activities of the intellectual elite, for discussing their interests, including the current important matters of the state. The acceptance of the European Enlightenment ideas in the Commonwealth owed much to the King's involvement.[14]

Other centers of artistic and political discourse came into prominence, at the expense of the royal court and its influence, with the increasing radicalization of public sentiment. In response to the detrimental for the country events, of which foreign domination and the partitions were the most disconcerting, new outlets for creative activity were formed. Hugo Kołłątaj's Kuźnica (Kołłątaj's Forge) of the Great Sejm period was one of the groups that wished to distance themselves from the royal court party. Other writers of the newer variety were supported by wealthy burgher patronage. They had all become very influential among the enlightened nobility and the general public of Warsaw, often originated from the dispossessed or otherwise degraded szlachta, and their writings straddled the realms of literature and political opinion journalism, published in many pamphlets. Franciszek Salezy Jezierski, a prolific writer before and around 1790, was a leading and compassionate critic of the szlachta government and defender of the lower social strata. Jakub Jasiński was a poet and general during the Kościuszko Uprising, a leader in the leftist Polish Jacobins faction. The more radical political writers rejected the concept of the "noble nation" and appealed to the entire population, often stressing the importance of its lower classes, peasantry and urban plebs, also in the struggle for independence.[14]

The other, distinctly different current in literature was influenced by French Rococo and based more directly on sentimentalism, increasingly popular in Europe since the publication of the romances of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In Poland the then fashionable folklore elements and peasant creativity works were, sometimes accurately and convincingly, utilized within the sentimentalist genres (e.g. pastorals). The most successful in this field were the lyrical poets, Franciszek Dionizy Kniaźnin and Franciszek Karpiński, who later became influential with the Romantic Era Polish writers.[14]

The sentimentalist writers and artists were supported by the Czartoryski magnate family. Related to the King, the Czartoryskis distanced themselves from him and in the 1780s fostered at their seat in Puławy the greatest provincial center of culture. Izabela Czartoryska's English park there was intended to mimic virgin nature and intimately relate the residence to its rustic, rather than urban surroundings. The Czartoryskis rivaled the royal court in their desire to constructively influence and reform the Commonwealth's nobility (still to be controlled by the magnate class), but operating in a different setting, they chose alternate ways of social persuasion and artistic expression. They stressed the country's historic traditions and the necessity of their evolution into a modern state and society.[14]

The Enlightenment brought also a revival of the Polish national theater. Polish language plays were initiated at Warsaw's main theater, upon Stanisław August's efforts, from 1765 (often French plays adapted or reworked by Franciszek Bohomolec and later Franciszek Zabłocki). The first full-fledged Polish plays were the patriotic The Return of the Deputy by Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz (1790) and the folklore-inspired Krakowiacy and Górale (names of ethnographic (folk) groups of southern Lesser Poland) by the long-term theater director Wojciech Bogusławski. The latter was staged as an innovative and uplifting opera spectacle right before the outset of the Kościuszko Insurrection.[14]

In the areas of music and visual or plastic arts there had been continuity with the preceding (Saxon monarchs) period. To add splendor to their position, the kings and the magnates kept and supported painters, sculptors, architects and musicians, who were of various nationalities, including Polish, German, French and Italian.[16]

The court of the Ogiński magnate family was musically inclined and the Ogińskis themselves produced two noted composers, Michał Kazimierz Ogiński and Michał Kleofas Ogiński. Maciej Kamieński, a Slovak settled in Poland, wrote the first Polish opera Misery Contented, staged in Warsaw in 1778.[17] The Czech Jan Stefani wrote the musical score for Krakowiacy and Górale. Besides the several Polish operas shown at various locations, instrumental styles of secular music were becoming more developed and popular, which had to do with the (characteristic of the times) general laicization of artistic tastes.[16]

In the flowering of architecture and painting the manner of classicism predominated, with more eclectic trends also present. Baroque and Rococo works continued in the second half of the 18th century and forms corresponding to literary sentimentalism appeared toward the end of the period.[16]

Churches and monastic quarters were built mostly in the Baroque style until the end of the 18th century. Rococo architecture coincided with the beginning of the Polish Enlightenment. It created finely decorated, more private and intimate chambers and other spaces, subordinate structures into which larger buildings were subdivided. Rococo is represented by the Mniszech family residential complex in Dukla and the Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw, rebuilt in that style by Efraim Szreger.[16]

The French-influenced classicistic structures were symmetrical, single buildings, often with colonnades and central domes. They were initiated in the 1760s because of Stanisław August's artistic preferences. The King had the interior of the Royal Castle redone and after 1783 the summer Łazienki Palace rebuilt in the style of classicism by Domenico Merlini. Łazienki park was decorated with sculptures by André Le Brun. The Protestant Holy Trinity Church in Warsaw (architect Szymon Bogumił Zug) was patterned after the Pantheon of Rome and the classical style was imitated in many burgher residencies in cities and provincial palaces of the nobility. The most representative type of the szlachta manor house, complete with a tympanum over the entrance, was formed at that time.[16]

The castle in Warsaw and Łazienki Palace were decorated by paintings of Marcello Bacciarelli, who also produced many portraits, including Polish historical, and spawned many talented younger native artists. Jean-Pierre Norblin, a French painter brought to Puławy by the Czartoryskis, created many current event, historical and landscape scenes of striking individuality and realism. His artistic influence became fully realized in the 19th century. Among the Polish painters, Franciszek Smuglewicz and Józef Peszka, professors at Vilnius and Cracow, were the leading figures. Tadeusz Kuntze worked mostly in Rome, and Daniel Chodowiecki in Berlin.[16]

First reforms, szlachta uprising, First Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian state

[edit]Familia reforms and election of Stanisław August Poniatowski; religious dissent controversy and Confederation of Radom

[edit]

The final years of the reign of Augustus III accelerated the disintegration of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Corruption and anarchy sprang from the royal court circles and engulfed also the leading Czartoryski and Potocki factions. Hetman Jan Klemens Branicki, popular with regular szlachta, was among the leading oligarchs. Russia emerged form the Seven Years' War as the main victorious power, and, aligned with Prussia, became decisively important in the affairs of the weak, subjected to foreign transgressions and incapable of independent functioning Commonwealth.[18]

Under the circumstances, the Familia party of the Czartoryskis looked toward an alliance with imperial Russia as the most viable for the Polish-Lithuanian state option. A particular opportunity seemed to have arisen from the fact that Stanisław Poniatowski, related and connected to their faction, had enjoyed a personal relationship with the new empress Catherine II, acquired during his recent stay as an envoy in St. Petersburg. The Czartoryskis, unpopular at that time with much of szlachta, intended essentially a coup d'état with Russian troops and the removal of the corrupt rule of Jerzy August Mniszech of the Saxon court. Familia petitioners supported Catherine's political moves in Courland, but due to the Tsaritsa's misgivings, their plans came to fruition only after the death of Augustus III.[18]

Invited by the Czartoryskis, the Russian forces entered the country and helped Familia to put the Convocation Sejm of 1764 under its control (Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski was the Marshal of the Sejm). The resistance of the "Republican" faction led by Hetman Branicki and Karol Radziwiłł was overcome and the opposition leaders had to leave the country. Andrzej Zamoyski then presented a program of constructive reforms, that included the majority rule in parliament, establishment of a permanent executive council (as recommended by Stanisław Konarski) and turning of the Republic's highest offices into collective organs. Frederick II and Prussian diplomats in cooperation with St. Petersburg and szlachta opposition were able to thwart much of the planned reform. The partial reforms pushed through with Catherine's support were still significant and constitute the beginning of the "enlightened" period, when the Polish-Lithuanian state attempted to adopt a variety of long overdue measures and thus save its existence. Parliamentary rules were made more functional, deputies were no longer bound by instructions issued by the local assemblies that delegated them (sejmiks), majority voting was imposed in matters involving the treasury and economics (which weakened the unanimity requirement enforced thus far by the liberum veto procedure). Military (hetman) and treasury highest officers were assigned respective parliamentary commissions that limited their power. The reform of matters important for the urban burgher class was also undertaken and included elimination of private customs and introduction of general customs, as well as partially limiting jurydykas.[18]

The royal election of 1764 took place in the presence of Russian troops. The szlachta electors gathered near Warsaw followed the wishes of the Empress and chose Stanisław Poniatowski, who became king as Stanisław August Poniatowski. To the Czartoryski party, the elevation of a man who was not a central or senior figure of their clan was after all something of a disappointment. This aspect affected their future relations with the King, who would also distance himself from Familia, and, lacking support of any major domestic faction or decisive personal character, develop strong dependence on his Russian sponsors. The new king was a man in his early thirties, thoroughly educated, reform-minded and familiar with political practices and relations in the Commonwealth and other European countries, as he had traveled extensively. Stanislaw August was a patron of arts and sciences; like other personalities of his era, he was particularly concerned with his own career and well-being. The King started the reign from a weak and handicapped position and later, often denied legitimacy and support from the nobility of the Commonwealth, had been unable to substantially improve his political standing. Yet Poniatowski was the person around whom the affairs of Poland-Lithuania would revolve for the federation's last three decades of existence and whose influence (and shortcomings) may have been decisive for its fate.[18]

The coronation and the Coronation Sejm took place in 1764, for the first (and last) time in Warsaw. A general confederation proclaimed already before the Convocation Sejm remained in force, which was a mechanism contrived so that a sejm could function as a veto-proof, easier to control confederated sejm. Steps were taken there to strengthen the recent successes of Familia legislators, and the King acted to facilitate a more efficient government. A regular conference of the King and his ministers was set up and monetary affairs reform was taken up by a special commission. "Committees of good order" were created for royal cities, to help with local treasury and economic matters. The new chancellor, Andrzej Zamoyski, took upon himself the protection of the cities. The state treasury revenues quickly rose. The establishment of the Corps of Cadets was a modest forerunner of the intended military reform. Already in 1765, however, Frederick II forced the abandonment of general customs, inconvenient to Prussian economic infiltration, and soon Catherine II herself, alarmed by the denunciations of the Polish opposition, moved against reforms, the reform movement and the King.[18]

The King and Familia were attacked by the Russian and Prussian interests, formally because of the situation of religious dissenters, that is non-Catholic Christians (Orthodox and Protestant), mostly non-nobility, whose political and religious rights in the Commonwealth had been considerably curtailed for a century or more, particularly in 1717 and 1733–1736. Members of the religious minorities had objected and appealed (to no avail) to Polish kings and parliaments and to their foreign supporters, who, invoking the appropriate clauses of the Treaty of Oliva of 1660 and the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686, intervened on numerous occasions at the Polish court. Stanisław August's new reign, combined with the Enlightenment toleration postulates, appeared to have had opened new opportunities for improvements in the religious dissent situation.[19]

The dissenter proposals, aimed at a return to the formerly practiced religious equality policies, were rejected at the Convocation Sejm in 1764, but upon foreign appeals made by the dissenters, had gained the support of Denmark, Russia and Prussia. The Familia party at that time rejected religious reform for the fear of antagonizing the masses of fanatically intolerant nobility and of encouraging regional political dissent in Royal Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, when they were trying to strengthen the dysfunctional central government. Their and the King's idea was to act on the matter gradually, first through a public education campaign, such as the articles published in the Monitor.[19]

Catherine II and Frederick II found the controversy a convenient pretext to intervene, and during the sejm of 1766, acting through their envoys Nicholas Repnin and Gédéon Benoît and taking advantage of the fierce opposition against Familia there, blocked further restrictions on liberum veto privileges. Under the protection of new Russian forces dispatched to Poland, the dissenters established confederations in Słuck and Thorn. Repnin initiated the establishment of the Radom Confederation of Catholic anti-Familia nobility, led by Karol Radziwiłł, ostensibly for the purpose of the defense of "faith and freedom". The confederates, hoping for a dethronement of Stanisław August, condemned the reforms and sent a delegation to the Empress, asking her to guarantee the traditional szlachta run system in the Commonwealth. Catherine and Repnin, acting to protect their own and the Empire's interests, would however disappoint to a large extent the Confederation of Radom petitioners (but thwart much of the reform as well).[19]

The humiliated Stanisław August was able to mend his relationship with Catherine and Repnin. At the sejm of 1767 Repnin demanded that the rights of religious minorities be restored. The demand was met with fierce opposition of Catholic zealots, let by Bishop Kajetan Sołtyk, whom Repnin had arrested and exiled into Russia. Repnin was supported by Gabriel Podoski, who became the head of the sejm committee preparing a new constitution of fundamental laws and was rewarded with the job of the primate.[19]

The old rights of religious dissenters, in the spheres of both public functions eligibility and religious practices freedom, were restored first. Catholicism was confirmed as the ruling religion nevertheless and apostasy remained subjected to severe punishments. The Sejm delegation then separated out the "immutable" cardinal laws of the state, including the "free election" of kings, liberum veto, the right to defy the king, nobility exclusive right to hold offices and possession of landed estates, rule over estate peasantry except for the imposition of the death penalty, the legal neminem captivabimus protection, union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and separate privileges historically enjoyed by Royal Prussia. The dissenter rights and the cardinal laws were guaranteed by Catherine II, which turned the Commonwealth into a Russian dependency or protectorate, because it was thus declared unable to change its own laws unilaterally.[19]

The remaining matters of the state and of the economy were to be decided by the sejm, with economic issues only subjected to majority voting. Stanisław August was prevented from forming the Permanent Council, a nascent executive government that he had been working on. The proposals were accepted by the "Repnin Sejm" over the protestation of Delegate Józef Wybicki in March 1768. The Radom confederates made peace with the King and for the time being it seemed that Repnin's policies had prevailed and would remain fully triumphant.[19]

Confederation of Bar, First Partition, Partition Sejm

[edit]

The Repnin Sejm legislation meant the end of the attempted imposition of reforms by Familia, but brought no peace or stability, as Repnin's ruthless personal rule turned against him both the disappointed magnate oligarchs and the regular gentry, who felt that their "freedoms" were under attack. The Sejm was still in session when on 29 February 1768 the Bar Confederation was formed in Bar in Podolia, with the ostensible goals of preserving the privileges of the Catholic religion and of the szlachta and independence of the state. The handful of local noblemen there were soon joined by their brethren from the surrounding voivodeships and some of the military forces. Józef Pułaski, the Marshal of the Confederation, had however only five thousand men with mediocre equipment at his disposal and they were soon overpowered by the superior Russian and royal Polish forces. The surrender of the confederates under Kazimierz Pułaski in fiercely defended Berdyczów was followed by that of Bar on 20 June. The confederation leaders and the remnants of their army found shelter in Moldavia within the Ottoman Empire, but some more years of unrest and rebellion (1768–1772) were still to follow.[20]

The Suplika of Torczyn pamphlet, calling for relief and rights for the peasants, was circulated in Volhynia in 1767. At the time of aggravated tensions among the rural populations, it contributed to the outbreak of Koliyivshchyna, or Ukrainian peasant revolt of 1768, the beginning of which coincided with the subduing of the szlachta uprising in Podolia. The peasant masses were made restless by the rumors of the Uniate Church's takeover of the Orthodox, of the Empress' support for a war against the Polish landowners and by the actual violations committed by the Confederation forces. Their resentment fueled further by the increased burdens that had to do with the expansion of the folwark economy east up to the Dnieper River, they moved violently against the szlachta and their Jewish tenants and property managers. The attacked suffered greatest losses in the town of Humań. The Ukrainian uprising, led by the Cossack commanders Ivan Gonta and Maksym Zalizniak, was ruthlessly suppressed by the Polish Crown and Russian forces, but resulted in disturbances in other parts of the Republic of Both Nations and prevented those, who were to continue the confederate warfare, from appealing to large scale peasant support.[20]

The szlachta challenges in the meantime picked up steam, as new confederations were being established in the western Crown provinces and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. A rebellion in Kraków, which took place soon after the fall of Bar, ended in capitulation after a month-long siege, but it was apparent that the fighting would go on. The outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War in October 1768 gave rise to new hopes for the confederates. France, in whose interest was the weakening of Russia, incited the Ottoman Empire to fight Russia and supported the confederate insurgents with money, arms and professional military cadres, while Austria provided asylum for the confederate supreme authority (the so-called Generality) that had been formed in 1769 in Biała.[20]

The confederates were, however, of divergent goals and interests. The magnate oligarchy wanted to remove Stanisław August and replace him with a Wettin ruler. The Generality declared the King's dethronement in 1770, just as Stanisław August contemplated the feasibility of abandoning Catherine and reaching an understanding with the Bar Confederation movement. The middle nobility fought for national independence, but under conservative assumptions of inviolability of their own privileged position as well as of that of the Catholic Church, which limited the appeal of the entire undertaking (the army of the nobility-dominated uprising was mostly non-noble and the cities sympathized with the King). 200,000 had served in the armed insurrection, but no more than 10 to 20 thousand at any given time. The cavalry lacked equipment, discipline and training, the army as a whole lacked professional unified command and a significant infantry component. The ready-to-sacrifice confederates were no match for the Russian adversary, both in terms of military quality and quantity. The insurgency strategy was based on partisan harassment conducted at changing locales, which was ruining the country without generating a realistic possibility of ultimate victory.[20]

At the end of 1770 the confederates, led by the French adviser General Charles François Dumouriez and the insurgency's best commander Kazimierz Pułaski, attempted to establish a permanent line of defense along the banks of the upper Vistula, but they were able to hold onto Lanckorona and Tyniec only for a significant period. Attempts to renew fighting in Lithuania were unsuccessful, while Józef Zaremba achieved only temporary military gains in Greater Poland. The abortive abduction of the King in 1771 lessened the domestic and foreign support for the Confederation. In 1772, the forces of the foreign partition operation entered the country and the movement was nearing its end. The Wawel Castle garrison kept on resisting, and then, until 18 August, only the Częstochowa fortress under Kazimierz Pułaski. The uprising ended and the confederate leaders left the country.[20]

The Confederation of Bar forced a reevaluation of the Repnin-led strategy of Russia (and caused the downfall of the powerful envoy). The Empire, distracted militarily at the time of its major war with Turkey, decided to agree to the reduction of the territory of Russia's troublesome Polish ally, promoted by Frederick II the Great of Prussia, which led to the First Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[20]

The Kingdom of Prussia, having conquered Silesia, directed its expansion-oriented activities toward the mouth of the Vistula and Royal Prussia (a province of the Commonwealth) in general. But the first actual steps in the partitioning process were taken by Austria, which in 1769 took Spisz and in the following year the counties of Czorsztyn, Nowy Targ and Nowy Sącz. Frederick, who followed with the de facto territorial acquisitions of his own, cooperated with Joseph II, and when Catherine II was ready, the three commenced partition negotiations. The Russo-Prussian agreement was signed in early 1772 and then joined by Austria. The actual new borders were determined in the convention signed in St. Petersburg on 5 August 1772. The convention listed the decay of the state, anarchy and factionalism among the justifications for the partitioning of the Commonwealth's territories. At the time of the First Partition, Austria and Prussia most eagerly pursued the dismemberment of their weak neighbor and grabbed significant chunks of Polish lands, beyond the sometimes vague specifications of the convention; the eastern Grand Duchy parts and Inflanty Voivodeship (Polish Livonia) taken by Russia were of a more marginal importance.[21]

Prussia, the initiator of the partition scheme, gained Ermland (Warmia), Pomerelia (Gdańsk Pomerania), Marienburg (Malbork) Voivodeship, Culmer Land (Chełmno Land) and middle-upper Noteć (Netze) River basin, but without Danzig (Gdańsk) and Thorn (Toruń), an area of 36,000 km2 with 580,000 inhabitants. Austria took the southern parts of the Kraków and Sandomierz Voivodeships and the Ruthenian Voivodeship, a total of 83,000 km2 and 2.65 million residents. Vienna bureaucrats gave the occupied area the name of Galicia and Lodomeria. The Russian partition amounted to 92,000 km2 and 1.3 million people. The army of the Commonwealth, 10,000 men at the most, attempted no resistance.[21]

The first partition left a still viable Poland-Lithuania (it became a buffer state for the three competing powers), but the country's economic potential was greatly reduced. Prussia controlled the lower Vistula, and therefore Polish agricultural exports; the salt mines were lost to Austria. Large concentrations of Poles now lived within the Prussian and Austrian states, which subjected them to Germanization pressures and lowered the percentage of ethnically Polish population in the remaining Commonwealth.[21]

The partitioning powers demanded that the Commonwealth officially approves of the partition and threatened further encroachments in case of refusal. King Stanisław August appealed to the European courts, but only individuals, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Gabriel Bonnot de Mably and Edmund Burke, condemned the partition. The "Partition Sejm" was summoned in 1773 and despite the objections of some of the deputies (notably Tadeusz Rejtan and Samuel Korsak), ratified under duress the partition convention. Unfavorable trade agreements, especially with Prussia, were also imposed. The partitioning powers were obviously inclined to intervene in the Polish affairs at will and the future of the Republic of Both Nations looked ominous.[21]

The Partition Sejm of 1773-1775 also instituted limited, but not insignificant improvements in the diminished state's political system and government. Frederick II and the Russian leader Nikita Panin had already decided not to allow substantial changes in the areas previously defined as the "cardinal laws". Their point of view was represented by Gédéon Benoît and the new Russian ambassador Otto Magnus von Stackelberg. The domestic opposition or reform factions had become exhausted. The Bar Confederation movement activists emigrated or were exiled to Siberia, Familia as well as the King that they bickered with now lacked broad popular support on the one hand and confidence of Empress Catherine on the other. Under the circumstances, the leading role was assumed by more mediocre personalities, such Marshal Adam Poniński, who led deliberations of the Partition Sejm.[22]

To prevent liberum veto disruptions the Sejm was set up as a confederation and a special delegation was convened to prepare and propose the new sejm "constitution" (legislation). The main controversy erupted over the issue of the establishment and form of the Permanent Council (Rada Nieustająca, an executive government), the need for which had become obvious by that time. The magnate clique led by August Kazimierz Sułkowki wanted to curtail decisively the influence of the King. But Stanisław August was able to convince the Russian interests of the need for an efficient government and create a council, where some of his prerogatives would be limited, but to a greater degree those of the previously very powerful magnate ministers, who were placed under the control of the new council. The Council, established finally in 1775, was led by the King, had 36 members elected, half from each chamber of the Sejm, and ruled by majority vote (the King decided in case of a tie). The ministers were supervised by five parallel departments of the Council: Foreign Interests, Police or Good Order, Military, Justice and Treasury. The Council, in addition to its administrative duties, would present to the King three candidates for each nomination to the Senate and other main offices.[22]

The army, modernized and reorganized, was to be enlarged to 30,000 and supported by taxes and customs introduced within the postulated treasury reform. Economic difficulties prevented, as on many occasions before, the accomplishment of the goals and the state was able to maintain only a half of the intended armed forces.[22]

The one indisputable achievement of the 1773-1775 sejm was the establishment of the Commission of National Education, through which the country's educational system was to be modernized. Szlachta was allowed to engage in "urban" professions and improvements in the legal standing of their subjects were discussed, but not acted upon. The cardinal laws were gathered again, foreigners and children and grandchildren of a given ruler were prohibited from assuming the crown of the Commonwealth. The legislation produced was validated with guarantees from all three partitioning powers.[22]

Rada Nieustająca council and its prerogatives were to be challenged by magnate opposition led by Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, who tried to discredit before the Empress' court the new power establishment (the King, the Council and Ambassador Stackelberg). Their efforts were not successful and in 1776 the Military Department of the Council took over the practical control over the army and significant reductions of the power traditionally wielded by the hetmans were implemented. The King would nominate officers and command the Guard. The goal of the increase in the size of the military was ultimately abandoned.[22]

The reforms of the Partition Sejm, subject to intrigue and obstruction and never fully put into effect (especially the treasury-military aspects), had however become the necessary foundation for the establishment of the emerging "Republic Enlightened" movement. This turned out to be the case even though this sejm lacked (besides the monarch) enlightened leaders, like the ones that would soon become prominent in the era of the approaching Great Sejm reforms.[22]

Great Sejm and its reforms

[edit]Zamoyski Code, formation of the reform camp and reform proposals

[edit]

The attempts to reform and save the disintegrating Commonwealth had thus far achieved a small measure of success, while the country had lost chunks of its territory. It became apparent that a more fundamental renewal would be possible only after the younger, more enlightened magnates and broader masses of middle nobility involved themselves and supported the reform processes and goals. It was an uphill struggle, as most magnates still actively opposed the King (a diverse but cooperating younger oligarchy that included Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, Ignacy Potocki, Stanisław Kostka Potocki, Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, Seweryn Rzewuski and Michał Kazimierz Ogiński), while the nobility below tended to be conservative and politically disoriented.[23]

A great battle was fought over the Zamoyski Code. Andrzej Zamoyski, the former Crown Chancellor and Repnin's opponent, was commissioned by the sejm of 1776 to work on a legal code, aimed at unification of the laws of the Commonwealth. Among Zamoyski's collaborators were the reformers Joachim Chreptowicz and Józef Wybicki. Wybicki wrote in 1777 the Patriotic Letters, where he expounded the reform movement's main themes: strengthening of the central government and the new postulated relationships among the social classes, including in particular improvements in the condition of townspeople and peasants.[23]

The proposed code dealt with some of those matters, without disturbing the szlachta's fundamental privileges. For example, the larger cities would be able to send limited representations to sejm sessions, or, what was found by the detractors to be particularly offensive, mixed nobility-peasant marriages would be allowed. Papal bulls could be published only with permission from the state, which caused the Papal Nuncio Giovanni Andrea Archetti to energetically oppose, with the help of Ambassador Stackelberg, the proposed laws. Demagogic propaganda easily convinced the szlachta deputies and the sejm of 1780 decisively and amid hysterical uproar rejected the Code.[23]

During the 1780s, further polarization among the szlachta ruling class was taking place, but the reform camp was also getting stronger, because to many the necessity and inevitability of changes were becoming more apparent. The most conservative of the magnates postulated complete decentralization (in effect dissolution) of centers of power, but their progressive, enlightened young generation was increasingly following the path to effective reform. Political restlessness had taken hold also among the remaining social classes and found its expression in an unprecedented explosion of published polemical materials. Unofficial opinion-forming centers were active, including salon societies, such as the ones led by Izabela Czartoryska or Katarzyna Kossakowska, and Freemasonry.[23]

In the period preceding the Great Sejm, the writings and activities of politically independent scientists and reformers Stanisław Staszic and Hugo Kołłątaj were of particular importance. Both were members of Catholic clergy, but neither refrained from assuming at times socially radical positions.[24]

Stanisław Staszic (1755–1826) originated from a burgher family in Piła, extensively studied abroad, especially in Paris, and became the mentor of Andrzej Zamoyski's children. He published two important works: Remarks on the Life of Jan Zamoyski (1785) and Warnings for Poland (1787). Staszic advocated strengthening of royal power, hereditary succession, majority voting in the sejm and equal representation for townspeople and nobility there (as well as equal rights in general). The army had to be enlarged. Of the most fundamental importance were to him social and economic policies. He wanted domestic trade and crafts protected. The critically oppressed peasant class needed state protection and reform of their labor obligations; he saw their condition as the principal reason for the weakness of the Commonwealth. Staszic blamed the magnate class for the deteriorated state of the country.[24]

Hugo Kołłątaj (1750–1812) was more of a political activist. He originated from middle nobility of Volhynia. Kołłątaj studied in Rome and then became actively involved in the work of the Commission of National Education, especially conducting the reform of the Academy of Kraków. He wrote Anonymous Letters to Stanisław Małachowski and Political Right of the Polish Nation (both completed by 1790). Kołłątaj's views, close to those of Staszic, were more tactically adjustable to the opportunities of the moment and thus not free of contradictions. In the Great Sejm era he became the principal leader of the patriotic camp. Somewhat less radical than Staszic on social issues, Kołłątaj nevertheless made the assertion "the land where man is a slave cannot claim freedom". His principal concern was the reform of national government and some of his postulates found their ultimate expression in the Constitution of May 3, 1791, which he co-wrote.[24]

The young Józef Pawlikowski defended the serfs in the strongest of terms. He wrote On Polish Subjects (1788) and Political Thoughts for Poland (1790). He also promoted strong royal power, reining in the excesses of szlachta and political rights for townspeople.[24]

Kołłątaj's Forge group gave the fullest expression to anti-noble sentiments and condemnation of the near-anarchy brought about by the privileged. Plebeian values and the early French Revolution examples were frequently invoked. Franciszek Salezy Jezierski published in 1790 Sieyès' What Is the Third Estate? in Polish as The Ghost of the Late Bastille. The program of the French bourgeois was adopted, tailored to the situation in the Commonwealth and used as still another argument in the fight for the betterment of the Republic.[24]

Great Sejm and May 3, 1791 Constitution

[edit]

Success of the reform program depended not only on sufficient domestic support, but also on favorable international configuration of forces in central-eastern Europe. Of crucial importance would be breaking-up of the Russo-Prussian alliance. The War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779) and the Austro-Prussian conflict there resulted in no improvements in the situation of the Commonwealth. The United States War of Independence then assumed an international dimension and preoccupied West European interests. Its course was also observed and closely followed in the Commonwealth and many Poles, including Tadeusz Kościuszko and Casimir Pulaski, took part in the fighting on the colonists side.[25]

A new situation in Europe resulted from the Russian takeover of Crimea and the death of Frederick II. Prussia, allied with Britain and the Netherlands, developed an antagonistic relationship also with Russia, which together with Austria seemed to threaten the existence of the Ottoman Empire. Among the military and diplomatic moves and maneuvering taking place, Poland was encouraged to engage in closer cooperation with Prussia and to confront Russia, which encountered interest and willingness on the part of some circles and participants in the Commonwealth politics.[25]

There was the self-proclaimed Patriotic Party, led by aristocrats of pro-British and pro-Prussian sympathies, annoyed by the tsarist interventions in the Commonwealth, opposed to King Stanisław August and his pro-Russian policies. This faction was represented by members of the Puławy group: Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, Ignacy and Stanisław Potocki, and their associate Scipione Piattoli, an Italian active in Polish politics. They counted on a Polish–Prussian alliance they had envisaged as a means for regaining lands lost to the other partitioning powers, especially Austria. The other group of influential oligarchs was led by Seweryn Rzewuski, Franciszek Ksawery Branicki and Szczęsny Potocki. Their faction's previous unsuccessful experience with the Radom Confederation notwithstanding, in order to establish a magnate-ruled decentralized republic, they tried to overthrow the King, but with Russian help.[25]

Stanisław August himself went to Kaniv in Ukraine in 1787 to meet his former lover, Empress Catherine. He was hoping to get her to agree to the enlargement of the Commonwealth's army and his own increased power, offering in return help in Russia's war with the Ottoman Empire. Although the Empress was in no mood for making concessions at that time, in the following year, because of the war difficulties, Russia proposed a defense treaty and a participation of a Polish corps in the hostilities. In order to formalize the military alliance and strengthen the Commonwealth's forces, the King summoned a sejm to deliberate in Warsaw in the fall of 1788.[25]

A confederation was set up and was led by the marshals, Stanisław Małachowski and Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha. Unexpectedly, the deliberations of the Great Sejm took four years.[25]

The pro-Russian camp, charged with accomplishing the above goals, turned out to be ineffective. It consisted of the itself non-uniform, conservative anti-King faction on the one hand (the hetmans' party proper of Ksawery Branicki and Seweryn Rzewuski and other magnate-led groups, including the one of Szczęsny Potocki), and the King and his diverse "court party" on the other. The King's supporters included Chancellor Jacek Małachowski and perceived an alliance with Russia as a necessary element of Polish politics.[25]

The lack of unity and conflicts within the pro-Russian camp were taken advantage of by the possibly more numerous patriotic camp, advocates of reforms seeking independence from Russia with the help of an alliance with Prussia. The Puławy group and Stanisław Małachowski belonged here and they were often directed by Hugo Kołłątaj, himself not a sejm deputy. The patriotic camp had become dominant in the Sejm and was eventually able to convince the King to join their cause and to largely push through the legislative measures they favored.[25]

The early events of the French Revolution were taking place when the Great Sejm was in session. Accordingly, as feudal interests in Europe were being threatened, close attention was paid in Poland to the views expressed by burgher publicists and burgher leaders wanted to take advantage of the situation. Advised by Kołłątaj, Jan Dekert, President of Warsaw, summoned in November 1789 representatives of 141 royal cities to the Polish capital. There they signed the "Act of Unification of the Cities" and formed the Black Procession, which headed for the Royal Castle and handed in their postulates of greatly increased political and economic rights for residents of towns to the King and the Sejm. The 1789 peasant unrest also added to the fears of the revolution spreading to the Commonwealth. The sejm debate conducted against this background soon resulted in dramatic determinations.[25]

Prussian ambassador Ludwig Heinrich Buchholtz effectively proposed a replacement of the existing Polish-Russian alliance with a Polish–Prussian alliance, which to many sejm deputies seemed like a good opportunity for getting rid of the Russian protectorate. The Prussian offer was accepted, despite the opposition from the King and Ambassador Stackelberg and anti-Russian legislative measures were adopted. The greatly enlarged army would be 100,000 men strong. The control over the military was taken away from the hetmans and the Permanent Council and the new Military Commission was established; the Permanent Council, seen as an instrument of Russian meddling, was then eliminated. Strict neutrality was to be observed in respect to Russia's war with the Ottoman Empire and foreign forces were to leave the Commonwealth territory.[25]

The general enthusiasm generated by the reform had not been matched by a readiness to provide the necessary resources. The already partially reformed military consisted of no more than 18,500 soldiers (1788), and to enlarge that force, greatly improved finances and conscription methods were needed. With a half-year delay, in 1789 the Sejm passed a permanent 10% tax on szlachta profits, 20% on the income of the Catholic Church and other tax reforms. Municipal tax burdens had been repeatedly increased, but many rural property owners balked at paying their share and the Sejm was forced to reduce the numerical goal for the army to 65,000. Anachronistically small numbers were projected for the infantry component (about 50%), to provide employment for szlachta volunteers in the cavalry.[25]

Negotiations with Prussia continued under the new envoy Girolamo Lucchesini. The treaty was signed on March 29, 1790, despite the unresolved disagreements over Danzig and Thorn, which Prussia demanded but the Sejm would not give up. Prussia, however, soon lost interest in the alliance, because of the changing international situation, including a withdrawal of the Austrian threat to the Ottoman Empire. To Prussian politicians, cooperation with Russia appeared again to be their best bet for further territorial acquisitions at the expense of the Polish neighbor.[25]

The "patriots" in the Sejm went ahead with the reform plans nevertheless. The Deputation for the Betterment of the Form of the Government was appointed in 1789 to hasten the preparations. The King now joined the patriotic camp and participated. The Sejm was not dissolved upon the expiration of its two-year term, but election was held in fall of 1790 to complement the body of deputies. The projected reforms had generally gained popularity and support in the sejmiks where the selection took place and nearly 2/3 of the new deputies became participants in the reform process, which appeared to enjoy broad support in various segments of society.[26]

Sejmiks themselves were reformed first. Only propertied szlachta could vote there from now, which deprived the magnates of much of their traditional clientele, but also violated the formal equality of nobles. Of great importance was the Free Royal Cities Act, passed on April 21, 1791, which satisfied the demands of the Black Procession. Townspeople gained personal legal inviolability, access to offices and distinctions, right to acquire rural land, independent self-government and limited representation in the sejm. Acquiring the noble status was made easier for burghers, while szlachta members would be allowed to practice trade and crafts in cities or hold offices there. Private towns were not included in the reform and full equality of the two estates was not realized, but the breakthrough legislation accomplished indisputable fundamental progress in political, social and economic relations. Considerable part of the conservative opposition no longer participated in the sejm debate and the statutes were passed without much resistance.[26]

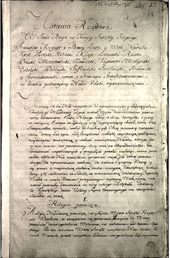

The most fundamental reform of the system was carried out by the patriots and the King on May 3, 1791, in a manner reminiscent of a coup d'état. The substance of the main government statute, in preparation for some time, was known only to a limited number of deputies. It was written mainly by Stanislaw August, Scipione Piattoli, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj. Contrary to the parliamentary rules, the general sejm assembly was not familiarized with the proposal in advance and the legislation was rushed through before many deputies had a chance to arrive (only about 1/3 were present). The session took place under pressure form numerous Warsaw residents gathered and reading of alarmist reports from abroad, with the King declaring the necessity of the law's immediate acceptance. Deputy Jan Suchorzewski dramatically protested, but then the Constitution was accepted and sworn amongst the celebrating crowd. The next day a protest was submitted by a small group of deputies, but on May 5 the matter was officially concluded and protests invalidated by the Constitutional Deputation of the Sejm. The entire affair was conducted, for the first time in the 18th century, without presence of foreign military forces or foreign pressures applied.[26]

The principal document produced was entitled the Government Statue (Ustawa Rządowa). It has since been often referred to as the second oldest constitution of this type, after the United States Constitution. It referred to the country's "citizens", which for the first time in Polish legislation was meant to include also townspeople and peasants, not just nobles. Nobility remained the privileged class, but the privilege was now practically limited to those with land property.[b] Their power over peasants became somewhat reduced, in that peasants were declared to be under the protection of the law and the government. New settlers arriving from abroad would enjoy personal freedom and landlords were encouraged to enter into contractual agreements with their rural tenants, which would specify obligations. The state had become involved and through enforcement of contracts able to intervene in the lord-serf relationship.[26]