History of radio receivers

Radio waves were first identified in German physicist Heinrich Hertz's 1887 series of experiments to prove James Clerk Maxwell's electromagnetic theory. Hertz used spark-excited dipole antennas to generate the waves and micrometer spark gaps attached to dipole and loop antennas to detect them.[1][2][3] These precursor radio receivers were primitive devices, more accurately described as radio wave "sensors" or "detectors", as they could only receive radio waves within about 100 feet of the transmitter, and were not used for communication but instead as laboratory instruments in scientific experiments and engineering demonstrations.

Spark era

[edit]

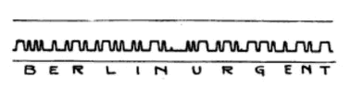

The first radio transmitters, used during the initial three decades of radio from 1887 to 1917, a period called the spark era, were spark gap transmitters which generated radio waves by discharging a capacitance through an electric spark.[5][6][7] Each spark produced a transient pulse of radio waves which decreased rapidly to zero.[1][3] These damped waves could not be modulated to carry sound, as in modern AM and FM transmission. So spark transmitters could not transmit sound, and instead transmitted information by radiotelegraphy. The transmitter was switched on and off rapidly by the operator using a telegraph key, creating different length pulses of damped radio waves ("dots" and "dashes") to spell out text messages in Morse code.[3][6]

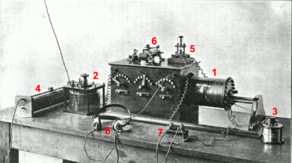

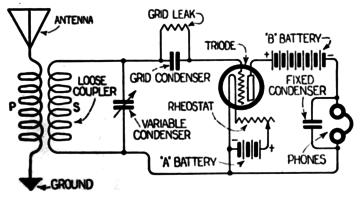

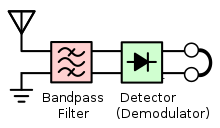

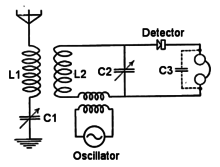

Therefore, the first radio receivers did not have to extract an audio signal from the radio wave like modern receivers, but just detected the presence of the radio signal, and produced a sound during the "dots" and "dashes".[3] The device which did this was called a "detector". Since there were no amplifying devices at this time, the sensitivity of the receiver mostly depended on the detector. Many different detector devices were tried. Radio receivers during the spark era consisted of these parts:[8]

- An antenna, to intercept the radio waves and convert them to tiny radio frequency electric currents.

- A tuned circuit, consisting of a capacitor connected to a coil of wire, which acted as a bandpass filter to select the desired signal out of all the signals picked up by the antenna. Either the capacitor or coil was adjustable to tune the receiver to the frequency of different transmitters. The earliest receivers, before 1897, did not have tuned circuits, they responded to all radio signals picked up by their antennas, so they had little frequency-discriminating ability and received any transmitter in their vicinity.[9] Most receivers used a pair of tuned circuits with their coils magnetically coupled, called a resonant transformer (oscillation transformer) or "loose coupler".

- A detector, which produced a pulse of DC current for each damped wave received.

- An indicating device such as an earphone, which converted the pulses of current into sound waves. The first receivers used an electric bell instead. Later receivers in commercial wireless systems used a Morse siphon recorder,[1] which consisted of an ink pen mounted on a needle swung by an electromagnet (a galvanometer) which drew a line on a moving paper tape. Each string of damped waves constituting a Morse "dot" or "dash" caused the needle to swing over, creating a displacement of the line, which could be read off the tape. With such an automated receiver a radio operator did not have to continuously monitor the receiver.

The signal from the spark gap transmitter consisted of damped waves repeated at an audio frequency rate, from 120 to perhaps 4000 per second, so in the earphone the signal sounded like a musical tone or buzz, and the Morse code "dots" and "dashes" sounded like beeps.

The first person to use radio waves for communication was Guglielmo Marconi.[6][10] Marconi invented little himself, but he was first to believe that radio could be a practical communication medium, and singlehandedly developed the first wireless telegraphy systems, transmitters and receivers, beginning in 1894–5,[10] mainly by improving technology invented by others.[6][11][12][13] [14][15] Oliver Lodge and Alexander Popov were also experimenting with similar radio wave receiving apparatus at the same time in 1894–5,[12][16] but they are not known to have transmitted Morse code during this period,[6][10] just strings of random pulses. Therefore, Marconi is usually given credit for building the first radio receivers.

Coherer receiver

[edit]

-

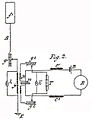

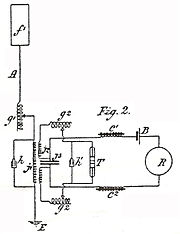

Circuit of Marconi's first coherer radio receiver from 1896

-

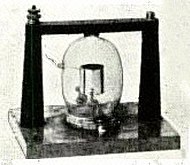

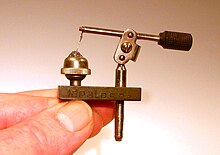

Coherer from 1904 as developed by Marconi.

The first radio receivers invented by Marconi, Oliver Lodge and Alexander Popov in 1894–5 used a primitive radio wave detector called a coherer, invented in 1890 by Edouard Branly and improved by Lodge and Marconi.[1][6][9][12][16][17][18] The coherer was a glass tube with metal electrodes at each end, with loose metal powder between the electrodes.[1][6][19] It initially had a high resistance. When a radio frequency voltage was applied to the electrodes, its resistance dropped and it conducted electricity. In the receiver the coherer was connected directly between the antenna and ground. In addition to the antenna, the coherer was connected in a DC circuit with a battery and relay. When the incoming radio wave reduced the resistance of the coherer, the current from the battery flowed through it, turning on the relay to ring a bell or make a mark on a paper tape in a siphon recorder. In order to restore the coherer to its previous nonconducting state to receive the next pulse of radio waves, it had to be tapped mechanically to disturb the metal particles.[1][6][16][20] This was done by a "decoherer", a clapper which struck the tube, operated by an electromagnet powered by the relay.

The coherer is an obscure antique device, and even today there is some uncertainty about the exact physical mechanism by which the various types worked.[1][11][21] However it can be seen that it was essentially a bistable device, a radio-wave-operated switch, and so it did not have the ability to rectify the radio wave to demodulate the later amplitude modulated (AM) radio transmissions that carried sound.[1][11]

In a long series of experiments Marconi found that by using an elevated wire monopole antenna instead of Hertz's dipole antennas he could transmit longer distances, beyond the curve of the Earth, demonstrating that radio was not just a laboratory curiosity but a commercially viable communication method. This culminated in his historic transatlantic wireless transmission on December 12, 1901, from Poldhu, Cornwall to St. John's, Newfoundland, a distance of 3500 km (2200 miles), which was received by a coherer.[11][15] However the usual range of coherer receivers even with the powerful transmitters of this era was limited to a few hundred miles.

The coherer remained the dominant detector used in early radio receivers for about 10 years,[19] until replaced by the crystal detector and electrolytic detector around 1907. In spite of much development work, it was a very crude unsatisfactory device.[1][6] It was not very sensitive, and also responded to impulsive radio noise (RFI), such as nearby lights being switched on or off, as well as to the intended signal.[6][19] Due to the cumbersome mechanical "tapping back" mechanism it was limited to a data rate of about 12-15 words per minute of Morse code, while a spark-gap transmitter could transmit Morse at up to 100 WPM with a paper tape machine.[22][23]

Other early detectors

[edit]

The coherer's poor performance motivated a great deal of research to find better radio wave detectors, and many were invented. Some strange devices were tried; researchers experimented with using frog legs[24] and even a human brain[25] from a cadaver as detectors.[1][26]

By the first years of the 20th century, experiments in using amplitude modulation (AM) to transmit sound by radio (radiotelephony) were being made. So a second goal of detector research was to find detectors that could demodulate an AM signal, extracting the audio (sound) signal from the radio carrier wave. It was found by trial and error that this could be done by a detector that exhibited "asymmetrical conduction"; a device that conducted current in one direction but not in the other.[27] This rectified the alternating current radio signal, removing one side of the carrier cycles, leaving a pulsing DC current whose amplitude varied with the audio modulation signal. When applied to an earphone this would reproduce the transmitted sound.

Below are the detectors that saw wide use before vacuum tubes took over around 1920.[28][29] All except the magnetic detector could rectify and therefore receive AM signals:

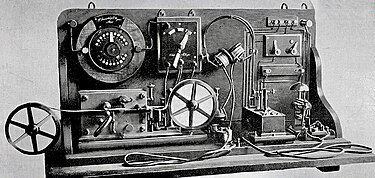

- Magnetic detector - Developed by Guglielmo Marconi in 1902 from a method invented by Ernest Rutherford and used by the Marconi Co. until it adopted the Audion vacuum tube around 1912, this was a mechanical device consisting of an endless band of iron wires which passed between two pulleys turned by a windup mechanism.[30][31][32][33] The iron wires passed through a coil of fine wire attached to the antenna, in a magnetic field created by two magnets. The hysteresis of the iron induced a pulse of current in a sensor coil each time a radio signal passed through the exciting coil. The magnetic detector was used on shipboard receivers due to its insensitivity to vibration. One was part of the wireless station of the RMS Titanic which was used to summon help during its famous 15 April 1912 sinking.[34]

- Electrolytic detector ("liquid barretter") - Invented in 1903 by Reginald Fessenden, this consisted of a thin silver-plated platinum wire enclosed in a glass rod, with the tip making contact with the surface of a cup of nitric acid.[1][31][35][36][37] The electrolytic action caused current to be conducted in only one direction. The detector was used until about 1910.[31] Electrolytic detectors that Fessenden had installed on US Navy ships received the first AM radio broadcast on Christmas Eve, 1906, an evening of Christmas music transmitted by Fessenden using his new alternator transmitter.[1]

- Thermionic diode (Fleming valve) - The first vacuum tube, invented in 1904 by John Ambrose Fleming, consisted of an evacuated glass bulb containing two electrodes: a cathode consisting of a hot wire filament similar to that in an incandescent light bulb, and a metal plate anode.[9][38][39][40] Fleming, a consultant to Marconi, invented the valve as a more sensitive detector for transatlantic wireless reception. The filament was heated by a separate current through it and emitted electrons into the tube by thermionic emission, an effect which had been discovered by Thomas Edison. The radio signal was applied between the cathode and anode. When the anode was positive, a current of electrons flowed from the cathode to the anode, but when the anode was negative the electrons were repelled and no current flowed. The Fleming valve was used to a limited extent but was not popular because it was expensive, had limited filament life, and was not as sensitive as electrolytic or crystal detectors.[38]

- Crystal detector (cat's whisker detector) - invented around 1904–1906 by Henry H. C. Dunwoody and Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, based on Karl Ferdinand Braun's 1874 discovery of "asymmetrical conduction" in crystals, these were the most successful and widely used detectors before the vacuum tube era[27][28] and gave their name to the crystal radio receiver (below).[31][41][42] One of the first semiconductor electronic devices, a crystal detector consisted of a pea-sized pebble of a crystalline semiconductor mineral such as galena (lead sulfide) whose surface was touched by a fine springy metal wire mounted on an adjustable arm.[9] This functioned as a primitive diode which conducted electric current in only one direction. In addition to their use in crystal radios, carborundum crystal detectors were also used in some early vacuum tube radios because they were more sensitive than the vacuum tube grid-leak detector.

During the vacuum tube era, the term "detector" changed from meaning a radio wave detector to mean a demodulator, a device that could extract the audio modulation signal from a radio signal. That is its meaning today.

Tuning

[edit]"Tuning" means adjusting the frequency of the receiver to the frequency of the desired radio transmission. The first receivers had no tuned circuit, the detector was connected directly between the antenna and ground. Due to the lack of any frequency selective components besides the antenna, the bandwidth of the receiver was equal to the broad bandwidth of the antenna.[7][9][17][43] This was acceptable and even necessary because the first Hertzian spark transmitters also lacked a tuned circuit. Due to the impulsive nature of the spark, the energy of the radio waves was spread over a very wide band of frequencies.[44][45] To receive enough energy from this wideband signal the receiver had to have a wide bandwidth also.

When more than one spark transmitter was radiating in a given area, their frequencies overlapped, so their signals interfered with each other, resulting in garbled reception.[7][43][46] Some method was needed to allow the receiver to select which transmitter's signal to receive.[46][47] Multiple wavelengths produced by a poorly tuned transmitter caused the signal to "dampen", or die down, greatly reducing the power and range of transmission.[48] In 1892, William Crookes gave a lecture[49] on radio in which he suggested using resonance to reduce the bandwidth of transmitters and receivers. Different transmitters could then be "tuned" to transmit on different frequencies so they did not interfere.[15][44][50] The receiver would also have a resonant circuit (tuned circuit), and could receive a particular transmission by "tuning" its resonant circuit to the same frequency as the transmitter, analogously to tuning a musical instrument to resonance with another. This is the system used in all modern radio.

Tuning was used in Hertz's original experiments[51] and practical application of tuning showed up in the early to mid 1890s in wireless systems not specifically designed for radio communication. Nikola Tesla's March 1893 lecture demonstrating the wireless transmission of power for lighting (mainly by what he thought was ground conduction[52]) included elements of tuning. The wireless lighting system consisted of a spark-excited grounded resonant transformer with a wire antenna which transmitted power across the room to another resonant transformer tuned to the frequency of the transmitter, which lighted a Geissler tube.[12][50] Use of tuning in free space "Hertzian waves" (radio) was explained and demonstrated in Oliver Lodge's 1894 lectures on Hertz's work.[53] At the time Lodge was demonstrating the physics and optical qualities of radio waves instead of attempting to build a communication system but he would go on to develop methods (patented in 1897) of tuning radio (what he called "syntony"), including using variable inductance to tune antennas.[54][55][56]

By 1897 the advantages of tuned systems had become clear, and Marconi and the other wireless researchers had incorporated tuned circuits, consisting of capacitors and inductors connected together, into their transmitters and receivers.[7][12][15][17][43][55] The tuned circuit acted like an electrical analog of a tuning fork. It had a high impedance at its resonant frequency, but a low impedance at all other frequencies. Connected between the antenna and the detector it served as a bandpass filter, passing the signal of the desired station to the detector, but routing all other signals to ground.[9] The frequency of the station received f was determined by the capacitance C and inductance L in the tuned circuit:

Inductive coupling

[edit]

In order to reject radio noise and interference from other transmitters near in frequency to the desired station, the bandpass filter (tuned circuit) in the receiver has to have a narrow bandwidth, allowing only a narrow band of frequencies through.[7][9] The form of bandpass filter that was used in the first receivers, which has continued to be used in receivers until recently, was the double-tuned inductively-coupled circuit, or resonant transformer (oscillation transformer or RF transformer).[7][12][15][17][55][57] The antenna and ground were connected to a coil of wire, which was magnetically coupled to a second coil with a capacitor across it, which was connected to the detector.[9] The RF alternating current from the antenna through the primary coil created a magnetic field which induced a current in the secondary coil which fed the detector. Both primary and secondary were tuned circuits;[43] the primary coil resonated with the capacitance of the antenna, while the secondary coil resonated with the capacitor across it. Both were adjusted to the same resonant frequency.

This circuit had two advantages.[9] One was that by using the correct turns ratio, the impedance of the antenna could be matched to the impedance of the receiver, to transfer maximum RF power to the receiver. Impedance matching was important to achieve maximum receiving range in the unamplified receivers of this era.[4][9] The coils usually had taps which could be selected by a multiposition switch. The second advantage was that due to "loose coupling" it had a much narrower bandwidth than a simple tuned circuit, and the bandwidth could be adjusted.[7][57] Unlike in an ordinary transformer, the two coils were "loosely coupled"; separated physically so not all the magnetic field from the primary passed through the secondary, reducing the mutual inductance. This gave the coupled tuned circuits much "sharper" tuning, a narrower bandwidth than a single tuned circuit. In the "Navy type" loose coupler (see picture), widely used with crystal receivers, the smaller secondary coil was mounted on a rack which could be slid in or out of the primary coil, to vary the mutual inductance between the coils.[7][58] When the operator encountered an interfering signal at a nearby frequency, the secondary could be slid further out of the primary, reducing the coupling, which narrowed the bandwidth, rejecting the interfering signal. A disadvantage was that all three adjustments in the loose coupler - primary tuning, secondary tuning, and coupling - were interactive; changing one changed the others. So tuning in a new station was a process of successive adjustments.

Selectivity became more important as spark transmitters were replaced by continuous wave transmitters which transmitted on a narrow band of frequencies, and broadcasting led to a proliferation of closely spaced radio stations crowding the radio spectrum.[9] Resonant transformers continued to be used as the bandpass filter in vacuum tube radios, and new forms such as the variometer were invented.[58][59] Another advantage of the double-tuned transformer for AM reception was that when properly adjusted it had a "flat top" frequency response curve as opposed to the "peaked" response of a single tuned circuit.[60] This allowed it to pass the sidebands of AM modulation on either side of the carrier with little distortion, unlike a single tuned circuit which attenuated the higher audio frequencies. Until recently the bandpass filters in the superheterodyne circuit used in all modern receivers were made with resonant transformers, called IF transformers.

Patent disputes

[edit]Marconi's initial radio system had relatively poor tuning limiting its range and adding to interference.[61] To overcome this drawback he developed a four circuit system with tuned coils in "syntony" at both the transmitters and receivers.[61] His 1900 British #7,777 (four sevens) patent for tuning filed in April 1900 and granted a year later opened the door to patents disputes since it infringed on the Syntonic patents of Oliver Lodge, first filed in May 1897, as well as patents filed by Ferdinand Braun.[61] Marconi was able to obtain patents in the UK and France but the US version of his tuned four circuit patent, filed in November 1900, was initially rejected based on it being anticipated by Lodge's tuning system, and refiled versions were rejected because of the prior patents by Braun, and Lodge.[62] A further clarification and re-submission was rejected because it infringed on parts of two prior patents Tesla had obtained for his wireless power transmission system.[63] Marconi's lawyers managed to get a resubmitted patent reconsidered by another examiner who initially rejected it due to a pre-existing John Stone Stone tuning patent, but it was finally approved it in June 1904 based on it having a unique system of variable inductance tuning that was different from Stone[64][65] who tuned by varying the length of the antenna.[62] When Lodge's Syntonic patent was extended in 1911 for another 7 years the Marconi Company agreed to settle that patent dispute, purchasing Lodge's radio company with its patent in 1912, giving them the priority patent they needed.[66][67] Other patent disputes would crop up over the years including a 1943 US Supreme Court ruling on the Marconi Company's ability to sue the US government over patent infringement during World War I. The Court rejected the Marconi Company's suit saying they could not sue for patent infringement when their own patents did not seem to have priority over the patents of Lodge, Stone, and Tesla.[12][50]

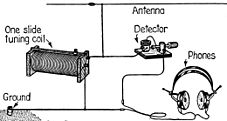

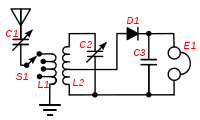

Crystal radio receiver

[edit]Although it was invented in 1904 in the wireless telegraphy era, the crystal radio receiver could also rectify AM transmissions and served as a bridge to the broadcast era. In addition to being the main type used in commercial stations during the wireless telegraphy era, it was the first receiver to be used widely by the public.[68] During the first two decades of the 20th century, as radio stations began to transmit in AM voice (radiotelephony) instead of radiotelegraphy, radio listening became a popular hobby, and the crystal was the simplest, cheapest detector. The millions of people who purchased or homemade these inexpensive reliable receivers created the mass listening audience for the first radio broadcasts, which began around 1920.[69] By the late 1920s the crystal receiver was superseded by vacuum tube receivers and became commercially obsolete. However it continued to be used by youth and the poor until World War II.[68] Today these simple radio receivers are constructed by students as educational science projects.

The crystal radio used a cat's whisker detector, invented by Harrison H. C. Dunwoody and Greenleaf Whittier Pickard in 1904, to extract the audio from the radio frequency signal.[9][31][70] It consisted of a mineral crystal, usually galena, which was lightly touched by a fine springy wire (the "cat whisker") on an adjustable arm.[31][71] The resulting crude semiconductor junction functioned as a Schottky barrier diode, conducting in only one direction. Only particular sites on the crystal surface worked as detector junctions, and the junction could be disrupted by the slightest vibration. So a usable site was found by trial and error before each use; the operator would drag the cat's whisker across the crystal until the radio began functioning. Frederick Seitz, a later semiconductor researcher, wrote:

Such variability, bordering on what seemed the mystical, plagued the early history of crystal detectors and caused many of the vacuum tube experts of a later generation to regard the art of crystal rectification as being close to disreputable.[72]

The crystal radio was unamplified and ran off the power of the radio waves received from the radio station, so it had to be listened to with earphones; it could not drive a loudspeaker.[9][71] It required a long wire antenna, and its sensitivity depended on how large the antenna was. During the wireless era it was used in commercial and military longwave stations with huge antennas to receive long distance radiotelegraphy traffic, even including transatlantic traffic.[73][74] However, when used to receive broadcast stations a typical home crystal set had a more limited range of about 25 miles.[75] In sophisticated crystal radios the "loose coupler" inductively coupled tuned circuit was used to increase the Q. However it still had poor selectivity compared to modern receivers.[71]

Heterodyne receiver and BFO

[edit]

Beginning around 1905 continuous wave (CW) transmitters began to replace spark transmitters for radiotelegraphy because they had much greater range. The first continuous wave transmitters were the Poulsen arc invented in 1904 and the Alexanderson alternator developed 1906–1910, which were replaced by vacuum tube transmitters beginning around 1920.[3]

The continuous wave radiotelegraphy signals produced by these transmitters required a different method of reception.[76][77] The radiotelegraphy signals produced by spark gap transmitters consisted of strings of damped waves repeating at an audio rate, so the "dots" and "dashes" of Morse code were audible as a tone or buzz in the receivers' earphones. However the new continuous wave radiotelegraph signals simply consisted of pulses of unmodulated carrier (sine waves). These were inaudible in the receiver headphones. To receive this new modulation type, the receiver had to produce some kind of tone during the pulses of carrier.

The first crude device that did this was the tikker, invented in 1908 by Valdemar Poulsen.[28][76] [78] This was a vibrating interrupter with a capacitor at the tuner output which served as a rudimentary modulator, interrupting the carrier at an audio rate, thus producing a buzz in the earphone when the carrier was present.[79] A similar device was the "tone wheel" invented by Rudolph Goldschmidt, a wheel spun by a motor with contacts spaced around its circumference, which made contact with a stationary brush.

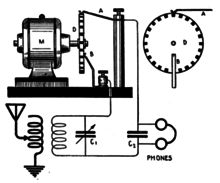

In 1901 Reginald Fessenden had invented a better means of accomplishing this.[76][78][80][81] In his heterodyne receiver an unmodulated sine wave radio signal at a frequency fO offset from the incoming radio wave carrier fC was generated by a local oscillator and applied to a rectifying detector such as a crystal detector or electrolytic detector, along with the radio signal from the antenna. In the detector the two signals mixed, creating two new heterodyne (beat) frequencies at the sum fC + fO and the difference fC − fO between these frequencies. By choosing fO correctly the lower heterodyne fC − fO was in the audio frequency range, so it was audible as a tone in the earphone whenever the carrier was present. Thus the "dots" and "dashes" of Morse code were audible as musical "beeps". A major attraction of this method during this pre-amplification period was that the heterodyne receiver actually amplified the signal somewhat, the detector had "mixer gain".[78]

The receiver was ahead of its time, because when it was invented there was no oscillator capable of producing the radio frequency sine wave fO with the required stability.[82] Fessenden first used his large radio frequency alternator,[79] but this was not practical for ordinary receivers. The heterodyne receiver remained a laboratory curiosity until a cheap compact source of continuous waves appeared, the vacuum tube electronic oscillator[78] invented by Edwin Armstrong and Alexander Meissner in 1913.[28][83] After this it became the standard method of receiving CW radiotelegraphy. The heterodyne oscillator is the ancestor of the beat frequency oscillator (BFO) which is used to receive radiotelegraphy in communications receivers today. The heterodyne oscillator had to be retuned each time the receiver was tuned to a new station, but in modern superheterodyne receivers the BFO signal beats with the fixed intermediate frequency, so the beat frequency oscillator can be a fixed frequency.

Armstrong later used Fessenden's heterodyne principle in his superheterodyne receiver (below).[78][79]

Vacuum tube era

[edit]

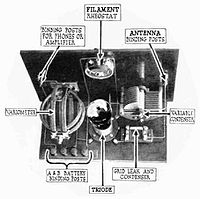

The Audion (triode) vacuum tube invented by Lee De Forest in 1906 was the first practical amplifying device and revolutionized radio.[38] Vacuum tube transmitters replaced spark transmitters and made possible four new types of modulation: continuous wave (CW) radiotelegraphy, amplitude modulation (AM) around 1915 which could carry audio (sound), frequency modulation (FM) around 1938 which had much improved audio quality, and single sideband (SSB).

The amplifying vacuum tube used energy from a battery or electrical outlet to increase the power of the radio signal, so vacuum tube receivers could be more sensitive and have a greater reception range than the previous unamplified receivers. The increased audio output power also allowed them to drive loudspeakers instead of earphones, permitting more than one person to listen. The first loudspeakers were produced around 1915. These changes caused radio listening to evolve explosively from a solitary hobby to a popular social and family pastime. The development of amplitude modulation (AM) and vacuum-tube transmitters during World War I, and the availability of cheap receiving tubes after the war, set the stage for the start of AM broadcasting, which sprang up spontaneously around 1920.

The advent of radio broadcasting increased the market for radio receivers greatly, and transformed them into a consumer product.[84][85][86] At the beginning of the 1920s the radio receiver was a forbidding high-tech device, with many cryptic knobs and controls requiring technical skill to operate, housed in an unattractive black metal box, with a tinny-sounding horn loudspeaker.[85] By the 1930s, the broadcast receiver had become a piece of furniture, housed in an attractive wooden case, with standardized controls anyone could use, which occupied a respected place in the home living room. In the early radios the multiple tuned circuits required multiple knobs to be adjusted to tune in a new station. One of the most important ease-of-use innovations was "single knob tuning", achieved by linking the tuning capacitors together mechanically.[85][86] The dynamic cone loudspeaker invented in 1924 greatly improved audio frequency response over the previous horn speakers, allowing music to be reproduced with good fidelity.[85][87] Convenience features like large lighted dials, tone controls, pushbutton tuning, tuning indicators and automatic gain control (AGC) were added.[84][86] The receiver market was divided into the above broadcast receivers and communications receivers, which were used for two-way radio communications such as shortwave radio.[88]

A vacuum-tube receiver required several power supplies at different voltages, which in early radios were supplied by separate batteries. By 1930 adequate rectifier tubes were developed, and the expensive batteries were replaced by a transformer power supply that worked off the house current.[84][85]

Vacuum tubes were bulky, expensive, had a limited lifetime, consumed a large amount of power and produced a lot of waste heat, so the number of tubes a receiver could economically have was a limiting factor. Therefore, a goal of tube receiver design was to get the most performance out of a limited number of tubes. The major radio receiver designs, listed below, were invented during the vacuum tube era.

A defect in many early vacuum-tube receivers was that the amplifying stages could oscillate, act as an oscillator, producing unwanted radio frequency alternating currents.[9][89][90] These parasitic oscillations mixed with the carrier of the radio signal in the detector tube, producing audible beat notes (heterodynes); annoying whistles, moans, and howls in the speaker. The oscillations were caused by feedback in the amplifiers; one major feedback path was the capacitance between the plate and grid in early triodes.[89][90] This was solved by the Neutrodyne circuit, and later the development of the tetrode and pentode around 1930.

Edwin Armstrong is one of the most important figures in radio receiver history, and during this period invented technology which continues to dominate radio communication.[79] He was the first to give a correct explanation of how De Forest's triode tube worked. He invented the feedback oscillator, regenerative receiver, the superregenerative receiver, the superheterodyne receiver, and modern frequency modulation (FM).

The first vacuum-tube receivers

[edit]This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (October 2020) |

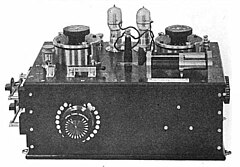

The first amplifying vacuum tube, the Audion, a crude triode, was invented in 1906 by Lee De Forest as a more sensitive detector for radio receivers, by adding a third electrode to the thermionic diode detector, the Fleming valve.[38][59][91][92] It was not widely used until its amplifying ability was recognized around 1912.[38] The first tube receivers, invented by De Forest and built by hobbyists until the mid-1920s, used a single Audion which functioned as a grid-leak detector which both rectified and amplified the radio signal.[59][89][93] There was uncertainty about the operating principle of the Audion until Edwin Armstrong explained both its amplifying and demodulating functions in a 1914 paper.[94][95][96] The grid-leak detector circuit was also used in regenerative, TRF, and early superheterodyne receivers (below) until the 1930s.

To give enough output power to drive a loudspeaker, 2 or 3 additional vacuum tube stages were needed for audio amplification.[59] Many early hobbyists could only afford a single tube receiver, and listened to the radio with earphones, so early tube amplifiers and speakers were sold as add-ons.

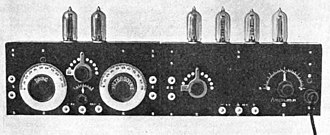

In addition to very low gain of about 5 and a short lifetime of about 30 – 100 hours, the primitive Audion had erratic characteristics because it was incompletely evacuated. De Forest believed that ionization of residual air was key to Audion operation.[97][98] This made it a more sensitive detector[97] but also caused its electrical characteristics to vary during use.[59][91] As the tube heated up, gas released from the metal elements would change the pressure in the tube, changing the plate current and other characteristics, so it required periodic bias adjustments to keep it at the correct operating point. Each Audion stage usually had a rheostat to adjust the filament current, and often a potentiometer or multiposition switch to control the plate voltage. The filament rheostat was also used as a volume control. The many controls made multitube Audion receivers complicated to operate.

By 1914, Harold Arnold at Western Electric and Irving Langmuir at GE realized that the residual gas was not necessary; the Audion could operate on electron conduction alone.[91][97][98] They evacuated tubes to a lower pressure of 10−9 atm, producing the first "hard vacuum" triodes. These more stable tubes did not require bias adjustments, so radios had fewer controls and were easier to operate.[91] During World War I civilian radio use was prohibited, but by 1920 large-scale production of vacuum tube radios began. The "soft" incompletely evacuated tubes were used as detectors through the 1920s then became obsolete.

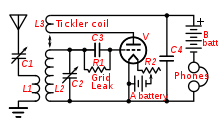

Regenerative (autodyne) receiver

[edit]

The regenerative receiver, invented by Edwin Armstrong[99] in 1913 when he was a 23-year-old college student,[100] was used very widely until the late 1920s particularly by hobbyists who could only afford a single-tube radio. Today transistor versions of the circuit are still used in a few inexpensive applications like walkie-talkies. In the regenerative receiver the gain (amplification) of a vacuum tube or transistor is increased by using regeneration (positive feedback); some of the energy from the tube's output circuit is fed back into the input circuit with a feedback loop.[9][89][101][102][103] The early vacuum tubes had very low gain (around 5). Regeneration could not only increase the gain of the tube enormously, by a factor of 15,000 or more, it also increased the Q factor of the tuned circuit, decreasing (sharpening) the bandwidth of the receiver by the same factor, improving selectivity greatly.[89][101][102] The receiver had a control to adjust the feedback. The tube also acted as a grid-leak detector to rectify the AM signal.[89]

Another advantage of the circuit was that the tube could be made to oscillate, and thus a single tube could serve as both a beat frequency oscillator and a detector, functioning as a heterodyne receiver to make CW radiotelegraphy transmissions audible.[89][101][102] This mode was called an autodyne receiver. To receive radiotelegraphy, the feedback was increased until the tube oscillated, then the oscillation frequency was tuned to one side of the transmitted signal. The incoming radio carrier signal and local oscillation signal mixed in the tube and produced an audible heterodyne (beat) tone at the difference between the frequencies.

A widely used design was the Armstrong circuit, in which a "tickler" coil in the plate circuit was coupled to the tuning coil in the grid circuit, to provide the feedback.[9][89][103] The feedback was controlled by a variable resistor, or alternately by moving the two windings physically closer together to increase loop gain, or apart to reduce it.[101] This was done by an adjustable air core transformer called a variometer (variocoupler). Regenerative detectors were sometimes also used in TRF and superheterodyne receivers.

One problem with the regenerative circuit was that when used with large amounts of regeneration the selectivity (Q) of the tuned circuit could be too sharp, attenuating the AM sidebands, thus distorting the audio modulation.[104] This was usually the limiting factor on the amount of feedback that could be employed.

A more serious drawback was that it could act as an inadvertent radio transmitter, producing interference (RFI) in nearby receivers.[9][89][101][102][103][105] In AM reception, to get the most sensitivity the tube was operated very close to instability and could easily break into oscillation (and in CW reception did oscillate), and the resulting radio signal was radiated by its wire antenna. In nearby receivers, the regenerative's signal would beat with the signal of the station being received in the detector, creating annoying heterodynes, (beats), howls and whistles.[9] Early regeneratives which oscillated easily were called "bloopers". One preventive measure was to use a stage of RF amplification before the regenerative detector, to isolate it from the antenna.[89][101] But by the mid-1920s "regens" were no longer sold by the major radio manufacturers.[9]

Superregenerative receiver

[edit]

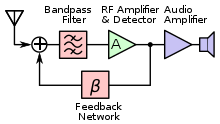

This was a receiver invented by Edwin Armstrong in 1922 which used regeneration in a more sophisticated way, to give greater gain.[90][106][107][108][109] It was used in a few shortwave receivers in the 1930s, and is used today in a few cheap high frequency applications such as walkie-talkies and garage door openers.

In the regenerative receiver the loop gain of the feedback loop was less than one, so the tube (or other amplifying device) did not oscillate but was close to oscillation, giving large gain.[106] In the superregenerative receiver, the loop gain was made equal to one, so the amplifying device actually began to oscillate, but the oscillations were interrupted periodically.[90][110] This allowed a single tube to produce gains of over 106.

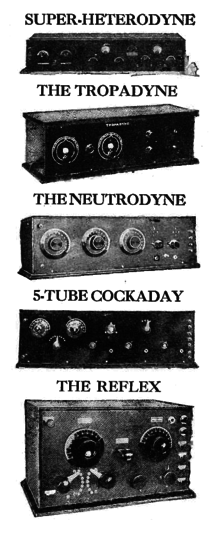

TRF receiver

[edit]The tuned radio frequency (TRF) receiver, invented in 1916 by Ernst Alexanderson, improved both sensitivity and selectivity by using several stages of amplification before the detector, each with a tuned circuit, all tuned to the frequency of the station.[9][90][110][111][112]

A major problem of early TRF receivers was that they were complicated to tune, because each resonant circuit had to be adjusted to the frequency of the station before the radio would work.[9][90] In later TRF receivers the tuning capacitors were linked together mechanically ("ganged") on a common shaft so they could be adjusted with one knob, but in early receivers the frequencies of the tuned circuits could not be made to "track" well enough to allow this, and each tuned circuit had its own tuning knob.[110][113] Therefore, the knobs had to be turned simultaneously. For this reason most TRF sets had no more than three tuned RF stages.[89][104]

A second problem was that the multiple radio frequency stages, all tuned to the same frequency, were prone to oscillate,[113][114] and the parasitic oscillations mixed with the radio station's carrier in the detector, producing audible heterodynes (beat notes), whistles and moans, in the speaker.[9][89][90][112] This was solved by the invention of the Neutrodyne circuit (below) and the development of the tetrode later around 1930, and better shielding between stages.[112]

Today the TRF design is used in a few integrated (IC) receiver chips. From the standpoint of modern receivers the disadvantage of the TRF is that the gain and bandwidth of the tuned RF stages are not constant but vary as the receiver is tuned to different frequencies.[114] Since the bandwidth of a filter with a given Q is proportional to the frequency, as the receiver is tuned to higher frequencies its bandwidth increases.[115][116]

Neutrodyne receiver

[edit]The Neutrodyne receiver, invented in 1922 by Louis Hazeltine,[117][118] was a TRF receiver with a "neutralizing" circuit added to each radio amplification stage to cancel the feedback to prevent the oscillations which caused the annoying whistles in the TRF.[9][90][112][113][119] In the neutralizing circuit a capacitor fed a feedback current from the plate circuit to the grid circuit which was 180° out of phase with the feedback which caused the oscillation, canceling it.[89] The Neutrodyne was popular until the advent of cheap tetrode tubes around 1930.

Reflex receiver

[edit]

The reflex receiver, invented in 1914 by Wilhelm Schloemilch and Otto von Bronk,[120] and rediscovered and extended to multiple tubes in 1917 by Marius Latour[120][121] and William H. Priess, was a design used in some inexpensive radios of the 1920s[122] which enjoyed a resurgence in small portable tube radios of the 1930s[123] and again in a few of the first transistor radios in the 1950s.[90][124] It is another example of an ingenious circuit invented to get the most out of a limited number of active devices. In the reflex receiver the RF signal from the tuned circuit is passed through one or more amplifying tubes or transistors, demodulated in a detector, then the resulting audio signal is passed again though the same amplifier stages for audio amplification.[90] The separate radio and audio signals present simultaneously in the amplifier do not interfere with each other since they are at different frequencies, allowing the amplifying tubes to do "double duty". In addition to single tube reflex receivers, some TRF and superheterodyne receivers had several stages "reflexed".[124] Reflex radios were prone to a defect called "play-through" which meant that the volume of audio did not go to zero when the volume control was turned down.[124]

Superheterodyne receiver

[edit]

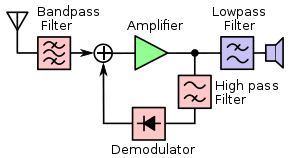

The superheterodyne, invented in 1918 during World War I by Edwin Armstrong[125] when he was in the Signal Corps, is the design used in almost all modern receivers, except a few specialized applications.[79][110][126] It is a more complicated design than the other receivers above, and when it was invented required 6 - 9 vacuum tubes, putting it beyond the budget of most consumers, so it was initially used mainly in commercial and military communication stations.[127] However, by the 1930s the "superhet" had replaced all the other receiver types above.

In the superheterodyne, the "heterodyne" technique invented by Reginald Fessenden is used to shift the frequency of the radio signal down to a lower "intermediate frequency" (IF), before it is processed.[115][127][128] Its operation and advantages over the other radio designs in this section are described above in The superheterodyne design

By the 1940s the superheterodyne AM broadcast receiver was refined into a cheap-to-manufacture design called the "All American Five", because it only used five vacuum tubes: usually a converter (mixer/local oscillator), an IF amplifier, a detector/audio amplifier, audio power amplifier, and a rectifier. This design was used for virtually all commercial radio receivers until the transistor replaced the vacuum tube in the 1970s.

Semiconductor era

[edit]The invention of the transistor in 1947 revolutionized radio technology, making truly portable receivers possible, beginning with transistor radios in the late 1950s. Although portable vacuum tube radios were made, tubes were bulky and inefficient, consuming large amounts of power and requiring several large batteries to produce the filament and plate voltage. Transistors did not require a heated filament, reducing power consumption, and were smaller and much less fragile than vacuum tubes.

Portable radios

[edit]

Companies first began manufacturing radios advertised as portables shortly after the start of commercial broadcasting in the early 1920s. The vast majority of tube radios of the era used batteries and could be set up and operated anywhere, but most did not have features designed for portability such as handles and built in speakers. Some of the earliest portable tube radios were the Winn "Portable Wireless Set No. 149" that appeared in 1920 and the Grebe Model KT-1 that followed a year later. Crystal sets such as the Westinghouse Aeriola Jr. and the RCA Radiola 1 were also advertised as portable radios.[129]

Thanks to miniaturized vacuum tubes first developed in 1940, smaller portable radios appeared on the market from manufacturers such as Zenith and General Electric. First introduced in 1942, Zenith's Trans-Oceanic line of portable radios were designed to provide entertainment broadcasts as well as being able to tune into weather, marine and international shortwave stations. By the 1950s, a "golden age" of tube portables included lunchbox-sized tube radios like the Emerson 560, that featured molded plastic cases. So-called "pocket portable" radios like the RCA BP10 had existed since the 1940s, but their actual size was compatible with only the largest of coat pockets.[129] But some, like the Privat-ear and Dyna-mite pocket radios, were small enough to fit a pocket.[130][131]

The development of the bipolar junction transistor in the early 1950s resulted in it being licensed to a number of electronics companies, such as Texas Instruments, who produced a limited run of transistorized radios as a sales tool. The Regency TR-1, made by the Regency Division of I.D.E.A. (Industrial Development Engineering Associates) of Indianapolis, Indiana, was launched in 1954. The era of true, shirt-pocket sized portable radios followed, with manufacturers such as Sony, Zenith, RCA, DeWald, and Crosley offering various models.[129] The Sony TR-63 released in 1957 was the first mass-produced transistor radio, leading to the mass-market penetration of transistor radios.[132]

Digital technology

[edit]

The development of integrated circuit (IC) chips in the 1970s created another revolution, allowing an entire radio receiver to be put on an IC chip. IC chips reversed the economics of radio design used with vacuum-tube receivers. Since the marginal cost of adding additional amplifying devices (transistors) to the chip was essentially zero, the size and cost of the receiver was dependent not on how many active components were used, but on the passive components; inductors and capacitors, which could not be integrated easily on the chip.[1] The development of RF CMOS chips, pioneered by Asad Ali Abidi at UCLA during the 1980s and 1990s, allowed low power wireless devices to be made.[134]

The current trend in receivers is to use digital circuitry on the chip to do functions that were formerly done by analog circuits which require passive components. In a digital receiver the IF signal is sampled and digitized, and the bandpass filtering and detection functions are performed by digital signal processing (DSP) on the chip. Another benefit of DSP is that the properties of the receiver; channel frequency, bandwidth, gain, etc. can be dynamically changed by software to react to changes in the environment; these systems are known as software-defined radios or cognitive radio.

Many of the functions performed by analog electronics can be performed by software instead. The benefit is that software is not affected by temperature, physical variables, electronic noise and manufacturing defects.[135]

Digital signal processing permits signal processing techniques that would be cumbersome, costly, or otherwise infeasible with analog methods. A digital signal is essentially a stream or sequence of numbers that relay a message through some sort of medium such as a wire. DSP hardware can tailor the bandwidth of the receiver to current reception conditions and to the type of signal. A typical analog only receiver may have a limited number of fixed bandwidths, or only one, but a DSP receiver may have 40 or more individually selectable filters. DSP is used in cell phone systems to reduce the data rate required to transmit voice.

In digital radio broadcasting systems such as Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), the analog audio signal is digitized and compressed, typically using a modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) audio coding format such as AAC+.[136]

"PC radios", or radios that are designed to be controlled by a standard PC are controlled by specialized PC software using a serial port connected to the radio. A "PC radio" may not have a front-panel at all, and may be designed exclusively for computer control, which reduces cost.

Some PC radios have the great advantage of being field upgradable by the owner. New versions of the DSP firmware can be downloaded from the manufacturer's web site and uploaded into the flash memory of the radio. The manufacturer can then in effect add new features to the radio over time, such as adding new filters, DSP noise reduction, or simply to correct bugs.

A full-featured radio control program allows for scanning and a host of other functions and, in particular, integration of databases in real-time, like a "TV-Guide" type capability. This is particularly helpful in locating all transmissions on all frequencies of a particular broadcaster, at any given time. Some control software designers have even integrated Google Earth to the shortwave databases, so it is possible to "fly" to a given transmitter site location with a click of a mouse. In many cases the user is able to see the transmitting antennas where the signal is originating from.

Since the Graphical User Interface to the radio has considerable flexibility, new features can be added by the software designer. Features that can be found in advanced control software programs today include a band table, GUI controls corresponding to traditional radio controls, local time clock and a UTC clock, signal strength meter, a database for shortwave listening with lookup capability, scanning capability, or text-to-speech interface.

The next level in integration is "software-defined radio", where all filtering, modulation and signal manipulation is done in software. This may be a PC soundcard or by a dedicated piece of DSP hardware. There will be a RF front-end to supply an intermediate frequency to the software defined radio. These systems can provide additional capability over "hardware" receivers. For example, they can record large swaths of the radio spectrum to a hard drive for "playback" at a later date. The same SDR that one minute is demodulating a simple AM broadcast may also be able to decode an HDTV broadcast in the next. An open-source project called GNU Radio is dedicated to evolving a high-performance SDR.

All-digital radio transmitters and receivers present the possibility of advancing the capabilities of radio.[137]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Lee, Thomas H. (2004). The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed. UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0521835398.

- ^ Appleyard, Rollo (October 1927). "Pioneers of Electrical Communication part 5 - Heinrich Rudolph Hertz" (PDF). Electrical Communication. 6 (2): 67. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Phillips, Vivian J. (1980). Early Radio Wave Detectors. London: Inst. of Electrical Engineers. pp. 4–12. ISBN 978-0906048245.

- ^ a b Rudersdorfer, Ralf (2013). Radio Receiver Technology: Principles, Architectures and Applications. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1118647844.

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. (2001). The Science of Radio: With Matlab and Electronics Workbench Demonstration, 2nd Ed. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-0387951508.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Coe, Lewis (2006). Wireless Radio: A History. McFarland. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-0786426621.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McNicol, Donald (1946). Radio's Conquest of Space. Murray Hill Books. pp. 57–68. ISBN 9780405060526.

- ^ Rudersdorfer, Ralf (2013). Radio Receiver Technology: Principles, Architectures and Applications. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1118647844. Chapter 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Carr, Joseph (1990). Old Time Radios! Restoration and Repair. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-0071507660.

- ^ a b c Beauchamp, Ken (2001). History of Telegraphy. IET. pp. 184–186. ISBN 978-0852967928.

- ^ a b c d Nahin, Paul J. (2001) The Science of Radio, p. 53-56

- ^ a b c d e f g Klooster, John W. (2007). Icons of Invention. ABC-CLIO. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-0313347436.

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946). Radio's Conquest of Space. Murray Hill Books. pp. 37–45. ISBN 9780405060526.

- ^ Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0262082983.

- ^ a b c d e Sarkar et al. (2006) History of Wireless, p. 349-358, archive Archived 2016-05-17 at the Portuguese Web Archive

- ^ a b c Fleming, John Ambrose (1910). The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, 2nd Ed. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 420–428.

- ^ a b c d Stone, Ellery W. (1919). Elements of Radiotelegraphy. D. Van Nostrand Co. pp. 203–208.

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 18-21

- ^ a b c McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 107-113

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 38-42

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 57-60

- ^ Maver, William Jr. (August 1904). "Wireless Telegraphy To-Day". American Monthly Review of Reviews. 30 (2): 192. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Aitken, Hugh G.J. (2014). The Continuous Wave: Technology and American Radio, 1900-1932. Princeton Univ. Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1400854608.

- ^ Worthington, George (January 18, 1913). "Frog's leg method of detecting wireless waves". Electrical Review and Western Electrician. 62 (3): 164. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Collins, Archie Frederick (February 22, 1902). "The effect of electric waves on the human brain". Electrical World and Engineer. 39 (8): 335–338. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 198-203

- ^ a b Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 205-209

- ^ a b c d Marriott, Robert H. (September 17, 1915). "United States Radio Development". Proc. of the Inst. Of Radio Engineers. 5 (3): 184. doi:10.1109/jrproc.1917.217311. S2CID 51644366. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ Secor, H. Winfield (January 1917). "Radio Detector Development". Electrical Experimenter. 4 (9): 652–656. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946). Radio's Conquest of Space. Murray Hill Books. pp. 121–123. ISBN 9780405060526.

- ^ a b c d e f Stone, Ellery (1919) Elements of Radiotelegraphy, p. 209-221

- ^ Fleming, John Ambrose (1910) The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, p. 446-455

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 85-108

- ^ Stephenson, Parks (November 2001). "The Marconi Wireless Installation in R.M.S. Titanic". Old Timer's Bulletin. 42 (4). Retrieved May 22, 2016. copied on Stephenson's marconigraph.com personal website

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 115-119

- ^ Fleming, John Ambrose (1910) The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, p. 460-464

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 65-81

- ^ a b c d e Lee, Thomas H. (2004) The Design of CMOS Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed., p. 9-11

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 157-162

- ^ Fleming, John Ambrose (1910) The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, p. 476-483

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 123-131

- ^ Fleming, John Ambrose (1910) The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, p. 471-475

- ^ a b c d Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. pp. 89–100. ISBN 978-0262082983.

- ^ a b Aitken, Hugh 2014 Syntony and Spark: The origins of radio, p. 70-73

- ^ Beauchamp, Ken (2001) History of Telegraphy, p. 189-190

- ^ a b Kennelly, Arthur E. (1906). Wireless Telegraphy: An Elementary Treatise. New York: Moffatt, Yard and Co. pp. 173–183.

selective signaling.

- ^ Aitken, Hugh 2014 Syntony and Spark: The origins of radio, p. 31-48

- ^ Jed Z. Buchwald, Scientific Credibility and Technical Standards in 19th and early 20th century Germany and Britain, Springer Science & Business Media - 1996, page 158

- ^ Crookes, William (February 1, 1892). "Some Possibilities of Electricity". The Fortnightly Review. 51: 174–176. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c Rockman, Howard B. (2004). Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-0471697398.

- ^ Cecil Lewis Fortescue, Wireless Telegraphy, Read Books Ltd - 2013, chapter XIII

- ^ Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0262082983.

- ^ Peter Rowlands, Oliver Lodge and the Liverpool Physical Society, Liverpool University Press - 1990, page 117

- ^ Jed Z. Buchwald, Scientific Credibility and Technical Standards in 19th and early 20th century Germany and Britain, Springer Science & Business Media - 1996, pages 158-159

- ^ a b c Aitken, Hugh G.J. (2014). Syntony and Spark: The Origins of Radio. Princeton Univ. Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-1400857883.

- ^ Thomas H. Lee, The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits, Cambridge University Press - 2004, page 35

- ^ a b McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 242-253

- ^ a b Marx, Harry J.; Van Muffling, Adrian (1922). Radio Reception. New York: G. Putnam's Sons. pp. 95–103.

loose coupler variometer variocoupler.

- ^ a b c d e McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 254-259

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943). Radio Engineers' Handbook (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. p. 170.

- ^ a b c Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. pp. 91-99

- ^ a b Howard B. Rockman, Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists, John Wiley & Sons - 2004, page 198

- ^ U.S. Patent No. 649,621, 3/15/1900, and part of 645,576, 3/20/1900 (filed Sept. 2, 1897) Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. of America v. United States. United States v. Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. of America. 320 U.S. 1 (63 S.Ct. 1393, 87 L.Ed. 1731)

- ^ US Patent no. 714,756, John Stone Stone Method of electric signaling, filed: February 8, 1900, granted: December 2, 1902

- ^ Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. of America v. United States. United States v. Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. of America. 320 U.S. 1 (63 S.Ct. 1393, 87 L.Ed. 1731)

- ^ Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. p. 48

- ^ Susan J. Douglas, Listening in: Radio and the American Imagination, U of Minnesota Press, page 50

- ^ a b Basalla, George (1988). The Evolution of Technology. UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-521-29681-6.

- ^ Corbin, Alfred (2006). The Third Element: A Brief History of Electronics. AuthorHouse. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-4208-9084-6.

- ^ Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers. US Dept. of the Army. 1952. pp. 167–169.

- ^ a b c Williams, Lyle Russell (2006). The New Radio Receiver Building Handbook. Lulu. pp. 20–24. ISBN 978-1847285263.

- ^ Riordan, Michael; Lillian Hoddeson (1988). Crystal fire: the invention of the transistor and the birth of the information age. USA: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-0-393-31851-7.

- ^ Beauchamp, Ken (2001). History of Telegraphy. Institution of Electrical Engineers. p. 191. ISBN 978-0852967928.

- ^ Bucher, Elmer Eustice (1917). Practical Wireless Telegraphy. New York: Wireless Press. pp. 306.

- ^ Lescarboura, Austin C. (1922). Radio for Everybody. New York: Scientific American Publishing Co. pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c Lauer, Henri; Brown, Harry L. (1920). Radio Engineering Principles. McGraw-Hill. pp. 135–142.

tikker heterodyne.

- ^ Phillips, Vivian 1980 Early Radio Wave Detectors, p. 172-185

- ^ a b c d e McNicol, Donald (1946). Radio's Conquest of Space. New York: Murray Hill Books. pp. 133–136. ISBN 9780405060526.

- ^ a b c d e Lee, Thomas H. (2004) The Design of CMOS Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed., p. 14-15

- ^ US patent no. 1050441, Reginald A. Fessenden, Electrical signaling apparatus, filed July 27, 1905; granted January 14, 1913

- ^ Hogan, John V. L. (April 1921). "The Heterodyne Receiver". The Electric Journal. 18 (4): 116–119. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. (2001) The Science of Radio, p. 91

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 267-270

- ^ a b c McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 341-344

- ^ a b c d e Wurtzler, Steve J. (2007). Electric Sounds: Technological Change and the Rise of Corporate Mass Media. Columbia Univ. Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0231510080.

- ^ a b c Nebeker, Frederik (2009). Dawn of the Electronic Age: Electrical Technologies in the Shaping of the Modern World, 1914 to 1945. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0470409749.

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 336-340

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943) Radio Engineers' Handbook, p. 656

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Williams, Lyle Russell (2006). The New Radio Receiver Building Handbook. Lulu. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-1847285263.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lee, Thomas H. (2004) The Design of CMOS Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed., p. 15-18

- ^ a b c d Okamura, Sōgo (1994). History of Electron Tubes. IOS Press. pp. 17–22. ISBN 978-9051991451.

- ^ De Forest, Lee (January 1906). "The Audion; A New Receiver for Wireless Telegraphy". Trans. AIEE. 25: 735–763. doi:10.1109/t-aiee.1906.4764762. Retrieved March 30, 2021. The link is to a reprint of the paper in the Scientific American Supplement, Nos. 1665 and 1666, November 30, 1907 and December 7, 1907, p.348-350 and 354-356.

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943). Radio Engineers' Handbook (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 564–565.

- ^ Armstrong, Edwin (December 12, 1914). "Operating features of the Audion". Electrical World. 64 (24): 1149–1152. Bibcode:1916NYASA..27..215A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1916.tb55188.x. S2CID 85101768. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 180

- ^ Lee, Thomas H. (2004) The Design of CMOS Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed., p. 13

- ^ a b c Langmuir, Irving (September 1915). "The Pure Electron Discharge and its Applications in Radio Telegraphy and Telephony" (PDF). Proceedings of the IRE. 3 (3): 261–293. doi:10.1109/jrproc.1915.216680. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Tyne, Gerald F. J. (December 1943). "The Saga of the Vacuum Tube, Part 9" (PDF). Radio News. 30 (6): 30–31, 56, 58. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ Armstrong, Edwin H. (September 1915). "Some recent developments in the Audion receiver" (PDF). Proc. IRE. 3 (9): 215–247. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1915.216677. S2CID 2116636. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ Armstrong, Edwin H. (April 1921). "The Regenerative Circuit". The Electrical Journal. 18 (4): 153–154. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers, 1952, p. 187-190

- ^ a b c d Terman, Frederick E. (1943) Radio Engineers' Handbook, p. 574-575

- ^ a b c McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 260-262

- ^ a b Langford-Smith, F. (1953). Radiotron Designer's Handbook, 4th Ed (PDF). Wireless Press for RCA. pp. 1223–1224.

- ^ In the early 1920s Armstrong, David Sarnoff head of RCA, and other radio pioneers testified before the US Congress on the need for legislation against radiating regenerative receivers. Wing, Willis K. (October 1924). "The Case Against the Radiating Receiver" (PDF). Broadcast Radio. 5 (6): 478–482. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers, 1952, p. 190-193

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943). Radio Engineers' Handbook (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 662–663.

- ^ Williams, Lyle Russell (2006) The New Radio Receiver Building Handbook, p. 31-32

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 279-282

- ^ a b c d Dixon, Robert (1998). Radio Receiver Design. CRC Press. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-0824701611.

- ^ Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers, 1952, p. 170-175

- ^ a b c d McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 263-267

- ^ a b c Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers, 1952, p. 177-179

- ^ a b Terman, Frederick E. (1943). Radio Engineers' Handbook (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 438–439.

- ^ a b Army Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers, 1952, p. 195-197

- ^ Rembovsky, Anatoly; Ashikhmin, Alexander; Kozmin, Vladimir; et al. (2009). Radio Monitoring: Problems, Methods and Equipment. Springer Science and Business Media. p. 26. ISBN 978-0387981000.

- ^ US Patent No. 1450080, Louis Alan Hazeltine, "Method and electric circuit arrangement for neutralizing capacity coupling"; filed August 7, 1919; granted March 27, 1923

- ^ Hazeltine, Louis A. (March 1923). "Tuned Radio Frequency Amplification With Neutralization of Capacity Coupling" (PDF). Proc. of the Radio Club of America. 2 (8): 7–12. Retrieved March 7, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943). Radio Engineers' Handbook (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 468–469.

- ^ a b Grimes, David (May 1924). "The Story of Reflex and Radio Frequency" (PDF). Radio in the Home. 2 (12): 9–10. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ US Patent no. 1405523, Marius Latour Audion or lamp relay or amplifying apparatus, filed December 28, 1917; granted February 7, 1922

- ^ McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 283-284

- ^ "Reflexing Today: Operating economy with the newer tubes" (PDF). Radio World. 23 (17): 3. July 8, 1933. Retrieved January 16, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Langford-Smith, F. (1953). Radiotron Designer's Handbook, 4th Ed (PDF). Wireless Press for RCA. pp. 1140–1141.

- ^ Armstrong, Edwin H. (February 1921). "A new system of radio frequency amplification". Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers. 9 (1): 3–11. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Lyle Russell (2006) The New Radio Receiver Building Handbook, p. 28-30

- ^ a b McNicol, Donald (1946) Radio's Conquest of Space, p. 272-278

- ^ Terman, Frederick E. (1943) Radio Engineers' Handbook, p. 636-638

- ^ a b c Michael B. Schiffer (1991). The Portable Radio in American Life. University of Arizona Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-0-8165-1284-3.

- ^ The Portable Radio in American Life

- ^ Popular Mechanics aug 1953

- ^ Skrabec, Quentin R. Jr. (2012). The 100 Most Significant Events in American Business: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–7. ISBN 978-0313398636.

- ^ Kim, Woonyun (2015). "CMOS power amplifier design for cellular applications: an EDGE/GSM dual-mode quad-band PA in 0.18 μm CMOS". In Wang, Hua; Sengupta, Kaushik (eds.). RF and mm-Wave Power Generation in Silicon. Academic Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-12-409522-9.

- ^ O'Neill, A. (2008). "Asad Abidi Recognized for Work in RF-CMOS". IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter. 13 (1): 57–58. doi:10.1109/N-SSC.2008.4785694. ISSN 1098-4232.

- ^ "History of the Radio Receiver". Radio-Electronics.Com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-16. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Britanak, Vladimir; Rao, K. R. (2017). Cosine-/Sine-Modulated Filter Banks: General Properties, Fast Algorithms and Integer Approximations. Springer. p. 478. ISBN 9783319610801.

- ^ Pizzicato Comes of Age