History of Montgomery, Alabama

| History of Alabama |

|---|

|

|

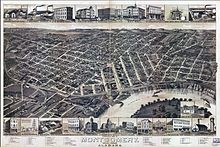

Montgomery, Alabama, was incorporated in 1819, as a merger of two towns situated along the Alabama River. It became the state capital in 1846. In February 1861, Montgomery was selected as the first capital of the Confederate States of America, until the seat of government moved to Richmond, Virginia, in May of that year.[1] During the mid-20th century, Montgomery was a primary site in the Civil Rights Movement, including the Montgomery bus boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches.[1]

Early settlement

[edit]Prior to European colonization, the left bank of the Alabama River was inhabited by the Alibamu tribe of Native Americans. The Alibamu and the Coushatta who lived on the opposite side the river were adept mound builders.[2] The first Europeans to come through central Alabama were Hernando de Soto and his expedition, who came through Ikanatchati and camped for one week in Towassa in 1540. It is also likely that Tristán de Luna y Arellano and his colonists traveled through the Montgomery area on their way from Nanipacana to Coosa in northwest Georgia.[2]

The next recorded European movements in the area happened well over a century later, when an expedition from Carolina went down the Alabama River in 1697. The first permanent European settler in the Montgomery area was James McQueen, a Scottish trader who came to the area in 1716.[2] In 1717, the French built Fort Toulouse to the northeast of the future Montgomery, serving primarily as a trading post with the Alibamu.[3] The British gained the former French and Spanish possessions east of the Mississippi River following the French and Indian War in 1764. In 1767, Alabama's area was divided between the Indian Reserve and British West Florida. The boundary line (32° 28′ north latitude) ran just north of present-day Montgomery. The northern portion later became part of the Province and later U.S. State of Georgia. The Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolutionary War, gave Georgia's territory to the United States. The southern border of the territory was disputed between Spain (who had received West Florida from the British in a separate treaty) and the United States until 1795, when the Treaty of San Lorenzo gave the land north of the 31st parallel to the United States.[4] This part of West Florida, including the southern half of Montgomery, became part of the Mississippi Territory in 1797. Georgia's western territory was integrated into Mississippi in 1804.[5]

After McQueen's arrival, European immigration to the area was slow in coming; Abraham Mordecai of Pennsylvania arrived in 1785 and later brought the first cotton gin to Alabama.[6] Following the end of the Creek War in August 1814, the Creek tribes were forced to give the majority of their lands to the U.S., including most of central and southern Alabama. When the hostile faction of Creeks that populated the Alabama River's banks moved south, the area became open for white settlers.[7] Between 1814 and 1816, Arthur Moore built a cabin near the current location of Union Station.[2]

Founding and early years

[edit]

In 1816, Montgomery County was formed, and its lands were sold off the next year at the federal land office in Milledgeville, Georgia. The first group of settlers to come to the Montgomery area was headed by General John Scott. The group founded Alabama Town about 2 miles (3 km) downstream from present-day downtown. In June 1818, county courts were moved from Fort Jackson to Alabama Town. Soon after, Andrew Dexter Jr. founded New Philadelphia, the present-day eastern part of downtown. Dexter envisioned his town would one day grow to prominence; he set aside a hilltop known as "Goat Hill" as the future location for the state capitol building. New Philadelphia soon prospered, and Scott and his associates built a new town adjacent, calling it East Alabama Town. The towns became rivals, but merged on December 3, 1819, and were incorporated as the city of Montgomery.[8] The new city was named for General Richard Montgomery, who died in the American Revolutionary War attempting to capture Quebec City, Canada. Montgomery County had already been named for Major Lemuel P. Montgomery, who fell at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in the Creek War.[2] A legacy of the towns' merger can be seen today in the alignment of downtown streets: streets to the east of Court Street are aligned in a north–south and east–west grid, while streets to the west are aligned parallel and perpendicular to the Alabama River.[9]

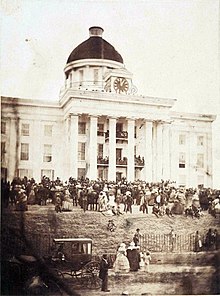

Due in large part to the cotton trade, the newly united Montgomery grew quickly. In October 1821, the steamboat Harriet began running along the Alabama River to Mobile.[10] In 1822, the city became the county seat, and a new courthouse was built at the present location of Court Square, at the foot of Market Street (now Dexter Avenue).[11] In April 1825, Marquis de Lafayette visited Montgomery on his grand tour of the United States.[12] In 1832, the Montgomery Railroad opened, and grew to reach West Point, Georgia by 1851.[13] Due in large part to its transportation connections and central location in the state, the legislature decided to move the state capital from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery, on January 28, 1846.[14] The city paid for the construction of the Capitol building on Goat Hill, the site set aside by Andrew Dexter 29 years earlier. The new building was ready for the 1847-48 legislature session, but on December 14, 1849, the building burned to the ground. It was rebuilt using the same plans and completed in 1851.[15]

Montgomery in the Civil War

[edit]As state capital, Montgomery began to have a great influence over state politics, but would also play a prominent role on the national stage. Montgomery resident William Lowndes Yancey served in both houses of the Alabama State Legislature and in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he became an outspoken supporter of states' rights. He traveled the country spreading his "fire-eater" stance of slavery and secession.[16] After Abraham Lincoln's election in 1860, Yancey led charge for Alabama's secession from the Union, which passed on January 11, 1861.[17] Beginning February 4, representatives from Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina met in Montgomery to form the Confederate States of America. Montgomery was named the first capital of the nation, and Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president on the steps of the State Capitol. The convention and subsequent Confederate government activities were based at the Exchange Hotel near Court Square. On April 11, the order to fire on Fort Sumter, the act which started the American Civil War, was sent from the Winter Building, which served as the telegraph office.[18] On May 29, 1861, the capital was moved to Richmond, Virginia, to be closer to the primary areas of battle. As a result, Montgomery remained virtually untouched by conflict during the war. On April 12, 1865, following the Battle of Selma, Major General James H. Wilson captured Montgomery for the Union.[19]

Reconstruction and modernization

[edit]

In 1886 Montgomery became the first city in the United States to install citywide electric street cars along a system that was nicknamed the Lightning Route.[20] The system made Montgomery one of the first cities to "depopulate" its residential areas at the city center through transportation-facilitated suburban development. Cloverdale and Highland Park saw much of their growth during the height of the Lightning Route. On March 19, 1910, Montgomery became the winter home of the Wright brothers' Wright Flying School. The men frequented Montgomery and founded several airfields, one of which developed into Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base after the Wrights began working with the government to produce planes for military use.[21]

Civil Rights Movement

[edit]During the Red Summer of 1919, three African Americans were lynched over a two-day period.

According to University of Alabama historian David Beito, Montgomery "nurtured the modern civil rights movement."[22] In December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, sparking the Montgomery bus boycott. The Montgomery Improvement Association was created by Martin Luther King Jr., then the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and E.D. Nixon, a lawyer and local civil rights advocate, to organize the boycott. Nixon, along with Fred Gray and Clifford Durr, argued the case of Browder v. Gayle before the U.S. District Court in Montgomery. In June 1956, Judge Frank M. Johnson ruled that Montgomery's bus segregation was illegal. After the Supreme Court upheld the ruling in November, the city desegregated the bus system, and the boycott was ended.[23] King gained nationwide fame as a result of the Boycott. He remained in Montgomery until 1960, during which time he led the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[24]

In 1960, inspired by the Greensboro sit-ins, students from Alabama State College organized their own sit-in at the State Capitol's lunch counter to protest segregation. After the involved students were expelled at the insistence of Governor John Malcolm Patterson, thousands of students marched on the capitol.[25] On May 20, 1961, the Freedom Riders, attempting to test desegregation laws on inter-state buses, arrived in Montgomery. After meeting with violence in Anniston and Birmingham, Governor Patterson pledged to protect the riders during their journey from Birmingham to Montgomery, but Montgomery city police did not continue to protect the riders. They were met by a mob who beat the riders and Justice Department officials who attempted to intervene. Police eventually intervened—and served the riders with injunctions for inciting violence. Days later, more riders departed Montgomery to continue the ride, only to be arrested upon reaching Jackson, Mississippi.[26]

Martin Luther King would return to Montgomery in 1965. Local civil rights leaders in Selma had been protesting Jim Crow laws blocking Black people from registering to vote. Following the shooting of a man after a civil rights rally, the leaders decided to march to Montgomery to petition Governor George Wallace to allow free voter registration. After meeting with resistance from state troopers, an incident that became known as "Bloody Sunday", Dr. King joined the effort. The march began on March 21, after Judge Frank M. Johnson authorized the march. By March 24, the marchers reached Montgomery, and the group camped and held a rally at the City of St. Jude that night. The next morning, the march reached the Capitol, and King gave a speech, How Long, Not Long, to the crowd of 25,000.[27]

1967 fire

[edit]On February 7, 1967, a devastating fire broke out at Dale's Penthouse, a restaurant and lounge on the top floor of the Walter Bragg Smith apartment building (now Capital Towers) at 7 Clayton Street downtown. The fire started in the cloakroom due to a patron failing to extinguish a tobacco pipe properly before placing it in his coat pocket, and early efforts to extinguish it by the staff failed. The casualties included 26 dead,[28] including former Alabama Public Service Commissioner Ed Pepper, who had been indicted earlier that day by a Federal Grand Jury.[29] (Video account of fire)

Present day

[edit]Montgomery continues to grow and diversify. In 1985, longtime resident and former Postmaster General Winton Blount donated 250 acres (1 km2) of land for the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts and the Alabama Shakespeare Festival. ASF ranks as the fifth largest Shakespearean venue in the world.[30] 1996 saw the construction of Montgomery's first skyscraper, the RSA Tower.[31] In 2001, Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore erected a 5,280-pound (2,395 kg) monument of the Ten Commandments in the Supreme Court building rotunda. The ensuing demonstrations by supporters and opponents alike brought national attention to Montgomery.[32] In 2005, Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama was founded, marking South Korean automaker Hyundai Motor Company's first manufacturing plant in the United States.[33] The city government is active in restoring the downtown area, and in 2007 adopted a master plan, which included revitalization of Court Square and the riverfront.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Montgomery: History - Early Days in Montgomery, Lafayette's Visit a Local Highlight, city-data.com, retrieved 2009-01-11

- ^ a b c d e Montgomery County, Alabama History, Montgomery County, Alabama, archived from the original on 2007-02-22, retrieved 2009-01-23

- ^ French Colonies in America - Fort Toulouse, University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ The Dominion of British West Florida History index, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Stein, Mark (2008), How the States Got Their Shapes (paperback edition), HarperCollins, pp. 11–17, ISBN 978-0-06-143138-8

- ^ Montgomery, Alabama, Goldring / Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, retrieved 2009-01-31

- ^ Ehle, John (1989), Trail of Tears The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation, Anchor Books Editions, ISBN 0-385-23953-X

- ^ Lewis, Herbert J. (August 31, 2007), "Montgomery County", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-01-31

- ^ Powell, Lyman Pierson (1904), Historic Towns of the Southern States, New York City: G. P. Putnam's Sons, p. 384, retrieved 2009-01-31

- ^ Powell, p. 393

- ^ Owen, p. 1038

- ^ Powell, p. 388

- ^ Hanson, Robert H., Historical Sketches: The Western Railway of Alabama, Old Alabama Rails, archived from the original on 2009-02-12, retrieved 2009-02-11

- ^ Neeley, Mary Ann Oglesby (November 6, 2008), "Montgomery", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Owen, p. 1039

- ^ Walther, Eric H. (2006), William Lowndes Yancey: The Coming of the Civil War, ISBN 978-0-7394-8030-4

- ^ The text of Alabama's Ordinance of Secession Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sulzby, James Fredrick (1989), Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts, University of Alabama Press, p. 128, ISBN 978-0-8173-5309-4, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Hébert, Keith S. (October 23, 2007), "Wilson's Raid", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Charles J. Van Depoele, retrieved 2008-12-14

- ^ Ennels, Jerome A. (October 8, 2007), "Wright Brother Flying School", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Beito, David (2009-05-02) Something is Rotten in Montgomery, LewRockwell.com

- ^ Hare, Ken, "Montgomery Bus Boycott: The story of Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement", Montgomery Advertiser, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Montgomery Improvement Association, Stanford University Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, retrieved 2009-05-02

- ^ Jeffries, Hasan Kwame (June 17, 2008), "Modern Civil Rights Movement in Alabama", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-03-28

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Timeline 1961: Freedom Rides, Civil Rights Movement Archive, retrieved 2009-03-28

- ^ Thornton III, J. Mills (March 14, 2007), "Selma to Montgomery March", Encyclopedia of Alabama, retrieved 2009-05-16

- ^ Dale's Penthouse Fire, gendisasters.com, retrieved 2012-12-11

- ^ PSC's Ed Pepper Indicted by Federal Grand Jury, al.com, retrieved 2012-12-11

- ^ Alabama Shakespeare Festival Presents Theater at its Best (PDF), Auburn University Elderhostel, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-18, retrieved 2009-01-11

- ^ RSA Towers, Montgomery, Emporis, Inc., archived from the original on February 28, 2007, retrieved 2008-08-23

- ^ Kleffman, Todd (2003-08-17), "Thousands rally for Commandments", Montgomery Advertiser

- ^ Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama; LLC, archived from the original on 2019-09-16, retrieved 2009-01-11

- ^ Montgomery Downtown Plan and SmartCode, Dover, Kohl, and Partners, archived from the original on 2016-01-13, retrieved 2008-08-23

Further reading

[edit]- Berney, Saffold (1878), "Montgomery", Handbook of Alabama, Mobile: Mobile Register print., OL 24232267M

- Benton, Jeffrey C. Through Others' Eyes: Published Accounts of Antebellum Montgomery, Alabama (NewSouth Books, 2014). online review

- Burton, Gary P., "The Founding Four Churches: An Overview of Baptist Beginnings in Montgomery County, Alabama", Baptist History and Heritage (Spring 2012), 47#1 pp 39–51.

- Newton, Wesley Phillips. "The origins and early development of civil aviation in Montgomery, 1910-1946." Alabama Review 57.1 (2004): 6-25 [1].

- Newton, Wesley Phillips. Montgomery in the Good War: Portrait of a Southern City, 1939–1946 (U of Alabama Press, 2000).

- Rogers, William Warren. Confederate Home Front: Montgomery During the Civil War (University of Alabama Press, 2001).

- Williams, Clanton W. "Early Ante-Bellum Montgomery: A Black-Belt Constituency." Journal of Southern History 7.4 (1941): 495-525. [2]

Black history and civil rights

[edit]- Hanbury, Dallas. "Documenting Slavery at the Local Level: Montgomery, Alabama; A Case Study." Alabama Review 73.3 (2020): 223-245. [3]

- Hines, Ralph H., and James E. Pierce. "Negro Leadership After the Social Crisis: An Analysis of Leadership Changes in Montgomery, Alabama." Phylon 26.2 (1965): 162-172. online

- Kennedy, Randall. "Martin Luther King's constitution: a legal history of the Montgomery bus boycott." Yale Law Journal 98 (1988): 999+ online.

- Kenny, Stephen C. "‘I can do the child no good’: Dr Sims and the Enslaved Infants of Montgomery, Alabama." Social history of medicine 20.2 (2007): 223-241. online

- Kohl, Herbert. "The politics of children's literature: The story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott." Journal of Education 173.1 (1991): 35-50.

- Phibbs, Cheryl Fisher. The Montgomery bus boycott: A history and reference guide (ABC-CLIO, 2009).

- Retzlaff, Rebecca. "Desegregation of city parks and the civil rights movement: the case of Oak Park in Montgomery, Alabama." Journal of Urban History 47.4 (2021): 715-752.