Great Wolford

| Great Wolford | |

|---|---|

Great Wolford and St Michael's Church | |

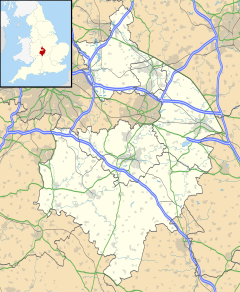

Location within Warwickshire | |

| Population | 278 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SP249345 |

| • London | 74 mi (119 km) SE |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Shipston-on-Stour |

| Postcode district | CV36 |

| Dialling code | 01608 |

| Police | Warwickshire |

| Fire | Warwickshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Great Wolford is a village and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district of Warwickshire, England. With the neighbouring parish of Little Wolford it is part of 'The Wolfords'.

History

[edit]According to A Dictionary of British Place Names, Wolford derives from the Old English 'wulf' with 'weard', meaning a "place protected against wolves". The Concise Oxfordshire Dictionary of English Place-names adds that 'weard' might mean "guard", and as such might here be unique usage, as an "arrangement for protection, [or] fence", the whole name perhaps "enclosure to protect flocks from wolves".[1][2]

In the Domesday Book, the settlement is variously listed as 'Ulware', 'Ulwarda' and 'Wolwarde', and in 1242 as 'Magna Wulleward'.[2] In 1086, after the Norman Conquest, Little Wolford was in the Hundred of Barcheston and county of Warwickshire. There were three Tenants-in-chief to king William I: Bishop Odo of Bayeux, Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester (Count of Meulan), and Robert de Stafford. Bishop Odo retained Gerald as his lord, who had acquired the title from the 1066 lord Aelfric (uncle of Thorkil) – the manor contained three villagers, one ploughland with 0.5 men's plough team, and 6 acres (2.4 ha) of meadow. The land of the Count of Meluan had Ralf as lord, again acquiring the title from the 1066 lord Aelfric - the manor contained three villagers, five smallholders, two slaves, and four ploughlands with one lord's plough team and one men's plough team. De Stafford had three manorial lands. Firstly, one where he was also Lord, this acquired from the 1066 lord Vagn (of Wootton), which contained eight villagers, eight smallholders, four slaves and a priest, with ten ploughlands, six men's plough teams and a mill. Secondly, one with Ordwy as lord, acquired from the 1066 lord Alwy, which contained four villagers, four smallholders, six ploughlands, and two lord's and one men's plough teams. Thirdly, where Alwin was the lord in 1066 and 1086, which contained four villagers, three smallholders, a slave, and two ploughlands with one lord's and one men's plough teams. In 1177 the church at Wolford was a gift from Henry II to the Augustinian Kenilworth Priory.[3][4][5]

After Robert de Stafford died (c.1100), his manor at Wolford passed through his sister Milicent de Stafford (who married Hervey Bagot), to her son Hervey de Stafford, who had adopted his mother's name. The manor was divided in 1242 at the time of the later Robert de Stafford, becoming Great and Little Wolford. Ownership of the two manors stayed with the Stafford family, including the 15th-century Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham. In 1521 Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham was executed by Henry VIII for treason. The year before he had, through trustees, sold the manors to Henry's courtier, Sir William Compton. The manors of Great and Little Wolford stayed in the Compton family until 1819, however, at about 1600 they were bought by Robert Catesby, the leader of the group of English Catholics who planned the failed 1605 Gunpowder Plot. They were then, in 1605, transferred to a Thomas Spencer and an Edward Sheldon, by Catesby, Sir Thomas Leigh, and Lord Ellesmere whose wife was sister to the second wife of Henry, Lord Compton. Because of transaction inconsistency, the manors reverted to the Compton family. In 1819 they were sold, by Charles Compton, Marquess of Northampton, to Lord Redesdale, they subsequently passing to his son John Freeman-Mitford, 1st Earl of Redesdale. The unmarried earl then left the manors to Algernon Bertram Mitford, created Baron Redesdale in 1902. After his death in 1916, the manors passed to David Freeman-Mitford, 2nd Baron Redesdale, the father of the Mitford sisters.[5]

During the 19th century Great Wolford, and its directory-listed parish hamlet of Little Wolford, was part of the Brailes division of the Kington Hundred. In 1801 parish population was 278, and in 1821, 529. By 1841 the township of Great Wolford, contained 311 inhabitants in 58 houses, and 583 in the whole parish, in an area of 2,671 acres (1,081 ha) with soil, "on the whole good", of clay, sand, gravel, and bog. Within the parish were "many" mineral springs, but not used medicinally. A school, erected in 1821 by Lord Redesdale, with attached schoolmaster's house, was mainly supported by subscription. The Church of St Michael accommodated seating for 460, of which 338 were free — not designated for particular persons. The incumbent's income was by a 'discharged vicarage' — all vicarages under ten pounds a year, and all rectories under ten marks, were discharged from the payment of first-fruits, also called annates, being the first year's revenues, together with one tenth of the income in all succeeding years. The previous Wolford tithes had been commuted — tithes were typically one-tenth of the produce or profits of parish land given to the rector for his services and were commuted under the 1836 Tithe Commutation Act, and usually substituted with a yearly rent-charge payment. The Wolford vicar's income was augmented by private benefactions of £400, Queen Anne's Bounty of £200, and a parliamentary grant of £300. Support for the incumbent also came from 81 acres (33 ha) in total of glebe—an area of land used to support a parish priest—and provision of a residence. Patronage (advowson) of the parish living was held by the Warden and Fellows of Merton College, Oxford. Lord Redesdale was lord of the manor and chief landowner. Directory listed trades and occupations in 1850 included the parish rector, a schoolmaster, the licensee of the Fox and Hounds public house, a corn miller, a carpenter, and eight farmers.[6][7]

The Samuel Lewis directory of 1850 mentions a mound of earth opened up in 1844, on the outskirts of an extensive wood near the "Oxford and Worcester road". Twenty skeletons were found, supposed to be those of persons slain near the spot of a skirmish during the war of the 17th century.[7]

By 1896 Great Wolford is recorded again as in the Brailes division of Kineton Hundred, and in the Brailes petty sessional division. It was in the Shipston-on-Stour Union—poor relief provision set up under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834—and county court district. The ecclesiastical parish was part of the Rural Deanery of South Kineton, and the Archdeaconry and Diocese of Worcester. St Michael's Church was restored in 1885, including reseated with open benches for 300 people, for a cost of £750. Its parish registers date to 1654 for births, 1656 for marriages, and 1665 for burials. The living was still a discharged vicarage, now with 36 acres (15 ha) of glebe, with residence, still in the gift of the Warden and Fellows of Merton College who were the appropriators. Lord of the manor was Bertram Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale) of Batsford Park, Moreton-in-Marsh. Land area was 1,344 acres (544 ha), growing wheat, oats, barley, beans and roots, and in which lived, in 1891, 202 people in the village, and 380 in the whole parish. There was a post box but no post office. The nearest money order office was at Long Compton, the nearest telegraph offices at Moreton-in-Marsh and Shipston-on-Stour. A National School for 70 children was erected in 1874 by Lord Redesdale; its average 1896 attendance was 61. Trades and occupations listed in 1896 included eight farmers, one of whom was also a haulier and two of whom were unmarried women of the same family, two carpenters, a blacksmith, and the licensee of the Fox and Hounds public house.[8]

Civil parish population in 1901 was 181, ecclesiastical, 362. On 7 June 1910 St Michael's Church was struck by lightning; repairs cost £130. The National School was now a Public Elementary School (Education Act 1902), with an average attendance of 57. Trades and occupations listed were eight farmers, again two of whom were unmarried women of the same family, one carpenter, a blacksmith, and the licensee of the Fox and Hounds public house.[9]

Although Little Wolford was described as a hamlet of Great Wolford (under 'Wolford') in 19th and 20th-century trade directories,[9] both had attained separate parish status under the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1866, which established new civil parishes for the purposes of the New Poor Law of 1834, and collection of poor rate.[10]

In 2019 a Village design statement (VDS) was drawn up for Great Wolford parish with aid from community involvement and supported by Stratford-on-Avon District Council and the National Lottery. The Statement describes the physical aspects of Wolford, and provides guidance on maintenance of parish character and any future development.[11]

Governance

[edit]The lowest tier of local government is through five elected councillors of Great Wolford Parish Council.[12] The next higher tier of government is Stratford-on-Avon District Council, to which Little Wolford sends one councillor under the Brailes and Compton ward,[13] above this, Warwickshire County Council, where Great Wolford is represented by the seat for the Shipston division of the Stratford-on-Avon area.[14]

Great Wolford is represented in the UK Parliament House of Commons as part of the Stratford-on-Avon constituency, its 2019 sitting MP being Nadhim Zahawi of the Conservative Party.

Prior to Brexit in 2020 it was part of the West Midlands constituency for the European Parliament.

Geography and community

[edit]Great Wolford, a civil parish at the south of Warwickshire, is entirely rural, of farms, fields, woods, dispersed businesses and residential properties, the only nucleated settlements being the village of Great Wolford with no amenities except a church and a bed & breakfast establishment, and the hamlet and farm of Nethercote. The parish is elongated in shape, 3 miles (5 km) north-east to south-west, and 1,200 yards (1,000 m) north-west to south-east at its widest. It borders the county of Gloucestershire with its parish of Todenham completely along the north-west side and defined by a tributary stream of Nethercote Brook, and Moreton-in-Marsh at the south-west corner. The Warwickshire parishes of Little Wolford, the boundary defined by the course of Nethercote Brook, a tributary of the River Stour, is at the east and Barton-on-the-Heath at the south-east. The south-east corner of the parish is part of the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). To the west of the AONB, at the south-west of the parish is the commercial Wolford Woods, a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), with facilities for glamping.[15][16][17]

There are four minor through-roads, all at the centre and the south-west of the parish, radiating from the village which sits at the central north-west edge of the parish, these to the settlements of Todenham at the north-west; to Little Wolford at the east; to Barton-on-the-Heath at the south-east; and to Moreton-in-Marsh at the south-west. The county town and city of Gloucester is 28 miles (45 km) to the south-west. Closest towns to the village are Moreton-in-Marsh, 3 miles (5 km) to the south-west, and Shipston-on-Stour, 4 miles (6 km) to the north. The neighbouring hamlet of Little Wolford is 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north-east. The nearest railway station is at Moreton-in-Marsh on the Cotswold Line of the Great Western Railway. Bus services operate within Great Wolford. The only stop, this in the village, includes connection to Shipston-on-Stour, Stretton-on-Fosse and Burmington on a circuitous village Shipston Link service. A further Villager Community Bus service includes connection to Moreton-in-Marsh, Bourton-on-the-Hill, Stow-on-the-Wold, Chipping Norton, and Little Compton.[15][16][17][18]

Wolford ecclesiastical parish includes Great Wolford and Little Wolford. The parish is part of the South Warwickshire Seven group of the Diocese of Coventry, which includes the other parishes of Barcheston, Barton-on-the-Heath, Burmington, Cherington with Stourton, Long Compton, and Whichford.[19]

The nearest primary school is Acorns Primary School at Long Compton,[20] the nearest secondary, Shipston High School.[21][22]

Landmarks

[edit]Great Wolford has six Grade II listed buildings and structures, all within the village.[23]

St Michael's Church (listed 1987), dating to 1833 and built by James Trubshaw on the site of a previous medieval church, is of limestone ashlar and comprises a chancel with vestry, nave and west tower. The buttressed chancel with polygonal pinacles, is listed as "short", and contains an east window in "15th-century style" by Heinersdorf of Berlin, and a vestry on its south side with internal and external access. The buttressed nave is of five bays with "13th-century-style" windows. Both chancel and nave are slate-roofed. The buttressed tower is of four stages; above its parapet rises an octagonal spire. At the west of the tower is the church main doorway portal, arched, and with hood mould with "carved head" label stops. The fourth stage is the belfry with abat-sons, and a ring of six bells, three originals dating to 1689, and three recast in the 18th and 19th century. The nave interior includes an 1876 pipe organ by Charles Martin of Oxford at the corner of the north wall and chancel arch, a wooden pulpit and reading desk, and an octagonal stone font, and late 17th or early 18th-century marble tablet memorials to the Ingram's family.[3][24][19][25][26] In the churchyard to the east of the chancel is a 1698 headstone (listed 1987), limestone, with a panel with "carved drapery surround" and dated inscription.[27]

There are two listed farmhouses: Manor Farmhouse (listed 1987) 30 yards (27 m) north-east from church, and Ash House Farmhouse (listed 1987) 200 yards (183 m) south-west from the church. Manor Farmhouse dates to the early 18th century and has additions from the 19th. Of L-plan, it is of two storeys with slate roof. The front aspect is of three window bays, one on the ground floor a canted bay—at an oblique angle to the wall—of 19th-century 'gothick' style with a battlemented parapet. At the rear of the building, included in the listing, is a two-storey range, with a 'gothick' porch. Listing for the interior includes, on the ground floor, 18th-century plank doors and stone flag-tiled floors.[28] Ash House Farmhouse is early to mid-18th century, constructed of limestone courses, of two storeys with casement windows, and an attic with 20th-century dormer windows.[29][30]

Fair View (listed 2019), 250 yards (229 m) south from the church, is a cottage dating to the 17th century, with additions and alterations from the 18th to 21st centuries. It is two storey with attic, of dressed Cotswold stone, and with a Welsh slate roof with a chimney stack at each gable end and attic windows. Windows are metal casements. It is of three-bay elevation with a central entrance and 20th-century porch. The interior is of two rooms with stone flag floor and historic plank and panelled doors. The cottage, orientated north to south, has a ground floor interior inglenook supported by a bressumer in the end wall of the south room, reflected by a chimney breast surrounded by a timber mantelpiece in the north room. A winder stair—stairs that change direction using angled treads—leads from the south room, through its first floor room, to the attic.[31]

The Fox and Hounds Inn (listed 1987), 300 yards (274 m) south-west from the church, originally a farmhouse, dates to the mid-17th century. Of L-shape plan and built in limestone courses with a stone tiled roof, it is of part two storeys, and of part one storey with an attic with three dormer windows. The interior has open beams, and an open fireplace with stone surround and braced by a timber bressumer. In 2003 The Fox and Hounds received a favourable review from The Daily Telegraph. In late 2018 the pub was up for sale for a guide price of £550,000 with an application for conversion to complete residential use, this after a 2016 closure following a locally controversial renovation and unsuccessful relaunch.[11][32][33][34][35]

Within the parish are nineteen historic and archaeological sites as scheduled monuments. These include a possible site of the 1016 Battle of Sherston (51°59′16″N 1°39′56″W / 51.987853°N 1.665651°W), fought between king Edmund Ironside, who died in the same year, and the Danes.[36] At Parsonage farm, 60 yards (55 m) south-west from the church, is the site of a farmhouse, rebuilt in 1900, and its pigeon house of c.1700 which still stands.[37][38] There are examples of defensive earthworks, and earthworks of medieval ridge and furrow cultivation, cropmarks, enclosures, dispersed evidence of ditches (some of late prehistoric or Roman origin), field boundaries, a limestone quarry and a sand pit. There are earthworks of medieval house platforms and hollow ways 120 yards (110 m) south from the church (52°00′29″N 1°38′11″W / 52.008147°N 1.636419°W). The earthworks of a Second World War bomb store, part of Moreton-in-Marsh airfield, are at the south-east of the parish at the edge of Wolford Woods (51°59′36″N 1°39′52″W / 51.993451°N 1.664415°W). The site of a Deserted medieval village (DMV) is map marked by English Heritage 850 yards (800 m) east from the village on Little Wolford Road at Nethercote (52°00′30″N 1°37′37″W / 52.00826°N 1.627057°W).[39]

References

[edit]- ^ Mills, Anthony David (2003); A Dictionary of British Place Names, Oxford University Press, revised edition (2011), p.506 ISBN 019960908X

- ^ a b Ekwall, Eilert (1936); The Concise Oxfordshire Dictionary of English Place-names, Oxford University Press, 4th ed. (1960), p.529 ISBN 0198691033

- ^ a b Historic England. "St Michaels Church (332787)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Wolford and Little Wolford", Open Domesday, University of Hull. Retrieved 16 October 2019

- ^ a b "Wolford", A History of the County of Warwick Volume 5, Kington Hundred, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1949), pp. 213-218. Retrieved 16 October 2019

- ^ "Little Wolford", A topographical dictionary of England, Samuel Lewis (London, 1848), vol. IV, p.643

- ^ a b "Wolford (Little)" in A History, Gazetteer & Directory of Warwickshire, Francis White (1850), pp.714, 715

- ^ Kelly's Directory of Warwickshire, 1896, p.274

- ^ a b Kelly's Directory of Warwickshire, 1912, p.323

- ^ Youngs, Frederic A., Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, citing 29 & 30 Vict c.113

- ^ a b "Great Wolford Village Design Statement - 2019", Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Great Wolford Parish Council. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ "Councillor Sarah Whalley-Hoggins", Stratford-on-Avon District Council. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ "Warwickshire Map divisions", Warwickshire County Council. Retrieved 18 October 2019

- ^ a b Extracted from "Great Wolford", Grid Reference Finder. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ a b Extracted from "Great Wolford", GetOutside, Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ a b Extracted from "Great Wolford", civil parish boundary, Google Maps. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ "Great Wolford", Bus Times. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ a b "South Warwickshire Seven", Diocese of Coventry. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Acorns Primary School. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Shipston High School at Shipston-on-Stour. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ "Great Wolford", Cotswold Homes. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ "Listed Buildings in Great Wolford, Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire", British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ St Michael's Church, Great Wolford, Warwickshire, Google Street View (image date July 2009). Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ "Great Wolford, St Michael and All Angels 6, 11-3-7 in Ab", Church Bells of Warwickshire. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ "9 valid peals for Great Wolford, S Michael & All Angels, Warwickshire, England", Felstead Database (includes photographs and video). Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Historic England. "Headstone Approximately 10 Metres East of Chancel of Church of St Michael (1186235)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Manor Farmhouse (1024283)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Ash House Farmhouse (1299317)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Michael (1024326)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Fair View (1464346)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Fox and Hounds Inn (1355504)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Fox and Hounds Inn, Great Wolford, Warwickshire, Google Street View (image date August 2016). Retrieved 17 October 2019

- ^ Jones, Tamlyn; "Historic Fox and Hounds pub in Great Wolford up for sale amid claims of hostile social media campaign", Birmingham Mail, 11 December 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2019

- ^ Burt, Paddy; "Room service: The Fox & Hounds, Great Wolford, Warwickshire", The Daily Telegraph, 4 October 2003. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Historic England. "Battle of Sherston (1554176)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Parsonage Farm (332832)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Post medieval dovecote at Parsonage Farm, Great Wolford", Our Warwickshire, Ourwarwickshire.org.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2019

- ^ Great Wolford, PastScape. Retrieved 25 October 2019

External links

[edit] Media related to Great Wolford at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Great Wolford at Wikimedia Commons- Great Wolford Parish Council

- South Warwickshire Seven, Diocese of Coventry.

- "Great Wolford", Our Warwickshire, Ourwarwickshire.org.uk

- Wolfords History, photographs and history articles web site