Grace Frick

Grace Frick | |

|---|---|

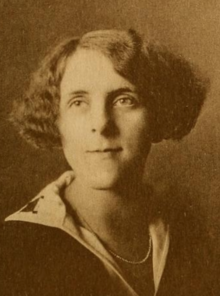

Frick from the 1925 Wellesley yearbook | |

| Born | Grace Marion Frick January 12, 1903 |

| Died | November 18, 1979 (aged 76) Northeast Harbor, Maine, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | College administrator, educator, translator |

| Partner | Marguerite Yourcenar |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | English |

| Institutions | |

Grace Marion Frick (January 12, 1903 – November 18, 1979) was an American translator and researcher for her lifelong partner, Belgian-French writer Marguerite Yourcenar.[1] Grace Frick taught languages at US colleges and was the second academic dean to be appointed to Hartford Junior College.

Early life

[edit]Grace Marion Frick was born in Toledo, Ohio, on January 12, 1903.[2][3] The family later moved to Kansas City, Missouri.[3]

Frick attended Wellesley College, receiving her bachelor's in 1925 and in 1927 earning a master's degree in English.[4][5] She worked on a dissertation at Yale University, starting in 1937, the same year she met Yourcenar in Paris, and completed academic work at University of Kansas.[3][1][4]

Career

[edit]Frick is most remembered for being the translator from French into English of Memoirs of Hadrian, The Abyss and Coup de Grâce by Marguerite Yourcenar.[3] Until Frick's death, Yourcenar allowed only her to translate her books.[6]

She taught at Stephens Junior College for Women (now Stephens College), Columbia, Missouri, and at Barnard College, New York City.[3][4][7] After Yourcenar's arrival, in 1940, Frick became the second academic dean of Hartford Junior College (later Hartford College for Women), until 1943, and they moved together at 549 Prospect Ave, West Hartford.[3][4] Other than administrative duties, Frick also taught English.[4] After Hartford, Frick taught at Connecticut College for Women (now Connecticut College), New London, Connecticut.[4]

While in Hartford, Frick and Yourcenar were active in the arts community that originated around the Wadsworth Atheneum headed by Arthur Everett Austin, Jr.[3]

Personal life

[edit]She met Marguerite Yourcenar in the February of 1937 at the Wagram Hotel, Paris.[8] They fell madly in love with one another and, in 1939, Grace invited Marguerite to come live with her in the United States, allowing the latter to escape the imminent war in Europe.[9]

Together they bought a house, "Petite Plaisance",[10] in 1950 in Northeast Harbor, Maine, on Mount Desert Island.[3][4] The two companions spoke French at home, loved horseback riding and lived a quiet life.[11][12] Frick and Yourcenar lived together for forty years until Frick died of cancer on November 18, 1979 at "Petite Plaisance".[3]

They are both buried at Brookside Cemetery, Mount Desert, Maine. Alongside them is a memorial plaque for Jerry Wilson, the last companion of Yourcenar, who died of AIDS in 1986.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "BECOMING THE EMPEROR How Marguerite Yourcenar reinvented the past". The New Yorker. February 14, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Edmund White (September 14, 1997). "The Celebration of Passion". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Grace Frick Dies; Was College Dean". Hartford Courant: 24. 25 November 1979. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Early Hartford College for Women History". University of Hartford Archives: Hartford College for Women and the WelFund. September 11, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Seniors are Honored for Academic Merit". The Wellesley News. June 23, 1927. p. 3.

- ^ Allen, Esther; Bernofsky, Susan (2013). In Translation: Translators on Their Work and What It Means. Columbia University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780231535021. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Bleier, Magda Palacci (1980). "After 300 Years, a Woman Writer (from Maine, 'Mon Dieu') Joins 'The Immortals' of France". People. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Savigneau, Josyane (1993). Marguerite Yourcenar: Inventing a Life [Marguerite Yourcenar: L'Invention d'une vie]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-226-73544-3.

- ^ Sarde, Michèle (1995). Vous, Marguerite Yourcenar: La passion et ses masques. Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, S.A. p. 13. ISBN 2-221-05930-1.

- ^ a b Litoff, Judy Barrett; McDonnell, Judith (1994). European Immigrant Women in the United States: A Biographical Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. p. 320. ISBN 9780824053062. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Deprez, Bérengère (2009). Marguerite Yourcenar and the USA: From Prophecy to Protest. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A. Éditions scientifiques internationales. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-5201-563-7.

- ^ Galey, Matthieu (1980). Marguerite Yourcenar de l'Académie française: Les yeux ouverts. Paris: Éditions du Centurion. pp. 243–249. ISBN 2-227-32022-2.

- 1903 births

- 1979 deaths

- LGBTQ people from Ohio

- Writers from Toledo, Ohio

- Writers from Kansas City, Missouri

- LGBTQ people from Missouri

- LGBTQ academics

- American LGBTQ writers

- Wellesley College alumni

- University of Kansas alumni

- Stephens College faculty

- Connecticut College faculty

- 20th-century American translators

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people