Gondhla

Gondhla (also called Gaṅdolā, Gandhola, Gondla, Kundlah) is a village in the Lahaul and Spiti district, Himachal Pradesh, India. It is located about 18 kilometres (11 mi) before Keylong on the road from Manali, Himachal Pradesh, and lies at 3,160 m (10,370 ft) above sea level. The village is famous for the Guru Ghantal monastery and the Gondhla fort.

Historical sites

[edit]Guru Ghantal Monastery

[edit]The Tibetan Buddhist monastery at Gondhla, locally known as the Guru Ghantal monastery, is said to have been founded by Padmasambhava in the 8th century.[1][2] It is now connected with the Drukpa Lineage of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, but its history long precedes the formation of that sect. According to local tradition and also the terma, the Padma bka'i thang, discovered in 1326 in the Yarlung Valley by Urgyan Lingpa, the site was associated with Padmasambhava.[3] Gondhla, like all the Drukpa monasteries in Ladakh and Lahaul and Spiti, owes allegiance to the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa, abbot of Hemis Monastery in Ladakh, who, in turn, owes allegiance to the head of the order in Bhutan.[4]

This site was possibly a Buddhist establishment even earlier than the time of Padmasambhava, as some ancient artefacts are associated with it. A chased copper goblet dated to the first century BCE was found near the monastery in 1857 by a British officer called Major Hay. This goblet is considered to be evidence of Buddhist monk cells being located in a cave monastery at that time. The frieze on the vase denotes a chariot procession and is considered one of the oldest examples of metalwork to be decorated in this way in India. Known as the Kulu Vase, it is now kept in the British Museum.[5] A damaged marble head of Avalokiteśvara also found here, is kept in the Guru Ghantal Monastery itself, and is claimed to date back to the time of Nagarjuna in the second century.[6] This seems to be the only monastery in the region other than Sani Monastery in Zanskar which has a history which is claimed to go back to the era of the Kushan Empire. There is also a black stone image of the goddess Vajreśvarī Devī (Wylie: rdo rje lha mo), and a wooden statue of the Buddha said to have been installed by the monk Rinchen Zangpo (958-1055), a famous lotsawa (translator of Sanskrit Buddhist texts).[2] The monastery has distinctive wooden (as opposed to clay) idols of Padmasambhava, Brijeshwari Devi and several other lamas.[7]

Originally, the monastery was probably a larger complex of purely Indian style of which nothing now remains. In 1959 the monastery underwent extensive repairs and a small pagoda roof of Kangra slates was added in a rather haphazard manner. The monastery got severely damaged in the 1975 Kinnaur earthquake, and was subsequently rebuilt with stone masonry, cement mortar, and CGI sheets.[2]

Gondhla fort

[edit]

Gondhla is also famous for its seven-story tower fort, which serves as the residence for the Thakurs of Gondhla. In earlier times, the Thakurs of Gondhla were the regents or viceroys of the Kullu Rajas in the Tinan valley of Lahaul, formerly also known as the 'Rangloi ilaqa'.[8][9][10] Tinan is the Lahuli name for the valley of the Chandra river, and includes includes all villages from Khoksar upto Tandi at the confluence of the Chandra and Bhaga rivers.[11] The tower is built in the Kathkuni style of Pahadi architecture, with alternating layers of stone and timber.[12]

According to some sources, the Gondhla fort was built around 1700 A.D. by Raja Man Singh of Kullu (who ruled over 1688-1719), after he married the daughter of Gondhla's Thakur.[13][14] But according to M.S. Randhawa, local tradition held that the fort was built much earlier by Thakur Rattan Pal, who was believed to have migrated from Bir in Kangra to Gondhla and became the feudal lord of this area. Randhawa also noted that the timber used in the Gondhla fort was cedar, which had been sourced from the forest of Dhungri in Manali, and had been transported over the Rohtang Pass.[15]

Over 1929-32, the Russian artist Nicholas Roerich spent summers in Lahaul, and among other subjects, made paintings on the Gondhla fort.[16][17]

The fort is now in disuse, but stores old weaponry, furniture, and many holy objects, such as thangkas, scriptures, and family deities of the Thakurs of Gondhla.[14][18]

Gallery

[edit]-

Gondhla Gompa altar

-

GondhlaṬhākur's seven-storey tower fort

-

Gondhla Gompa door.

-

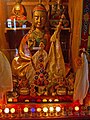

Padmasambhava statue - Gondhla Monastery.

-

Kulu Vase, discovered in the Monastery, now displayed in the British Museum

-

A small statue of Guru Rinpoche/Padmasambhava statue at Gondhla in 2010.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Francke (1926), Vol. II, pp. 211, 215, 223.

- ^ a b c Handa, Om Chand (2004). Buddhist Monasteries of Himachal. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-170-2.

- ^ Handa (1987), pp. 57, 69, 75-77.

- ^ Rose, H. A., et al. (1911), p. 249.

- ^ British Museum Highlights

- ^ Handa (1987), pp. 50-52.

- ^ "Lahaul and Spiti Tourism:Monasteries". District Lahaul & Spiti. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ Brentnall, Mark (2004). The Princely and Noble Families of the Former Indian Empire: Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-163-4.

- ^ Sahni, Ram Nath (1994). Lahoul, the Mystery Land in the Himalayas. Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7387-017-0.

- ^ Punjab District and State Gazetteers: Part A]. Compiled and published under the authority of the Punjab government. 1918.

- ^ Admin (18 June 2023). "Tinan Valley : A paradise north to the Atal Tunnel : Sissu and Gondhla - Safar with Sasha". Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ Mansingka, Shubham MansingkaShubham. "Tower fort of Gondhla". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ Ghosh, Tapash Kumar (2002). A Profile of the Himalayan Lahaula. Anthropological Survey of India, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Department of Culture, Government of India. ISBN 978-81-85579-52-8.

- ^ a b Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (2001). Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-115-3.

- ^ Randhawa, M.S. (1974). Travels in the Western Himalaya. Delhi: Thomson Press India. p. 202.

- ^ "Thakur of Gondla". Travel The Himalayas -Kashmir 360. 1 April 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ "Paintings". Roerich In Lahul. 5 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ Shabab, Dilaram (26 February 2019). Kullu: The Valley of Gods. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-93-86832-92-4.

References

[edit]- Handa, O. C. (1987). Buddhist Monasteries in Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85182-03-5.

- Kapadia, Harish. (1999). Spiti: Adventures in the Trans-Himalaya. Second Edition. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7387-093-4.

- Janet Rizvi. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Delhi. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Cunningham, Alexander. (1854). LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. London. Reprint: Sagar Publications (1977).

- Francke, A. H. (1977). A History of Ladakh. (Originally published as, A History of Western Tibet, (1907). 1977 Edition with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

- Francke, A. H. (1914, 1926). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Rose, H. A., et al. (1911). Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North West Frontier Province. Reprint 1990. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0505-3.

- Sarina Singh, et al. India. (2007). 12th Edition. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2.