Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR /ˈfɜːrbər/) is a conceptual entity–relationship model developed by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) that relates user tasks of retrieval and access in online library catalogues and bibliographic databases from a user’s perspective. It represents a more holistic approach to retrieval and access as the relationships between the entities provide links to navigate through the hierarchy of relationships. The model is significant because it is separate from specific cataloguing standards such as Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR), Resource Description and Access (RDA) and International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD).[1]

User tasks

[edit]The ways that people can use FRBR data have been defined as follows: to find entities in a search, to identify an entity as being the correct one, to select an entity that suits the user's needs, or to obtain an entity (physical access or licensing).[2]

FRBR comprises groups of entities:

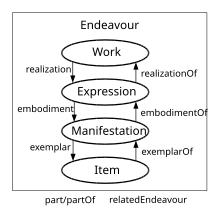

- Group 1 entities are work, expression, manifestation, and item (WEMI). They represent the products of intellectual or artistic endeavor.

- Group 2 entities are person, family and corporate body, responsible for the custodianship of Group 1’s intellectual or artistic endeavor.

- Group 3 entities are subjects of Group 1 or Group 2’s intellectual endeavor, and include concepts, objects, events, and places.

Group 1 entities are the foundation of the FRBR model:

- Work is a "distinct intellectual or artistic creation."[3] For example, Beethoven's Ninth Symphony apart from all ways of expressing it is a work. When we say, "Beethoven's Ninth is magnificent!" we generally are referring to the work.

- Expression is "the specific intellectual or artistic form that a work takes each time it is 'realized.'"[3] An expression of Beethoven's Ninth might be each draft of the musical score he writes down (not the paper itself, but the music thereby expressed).

- Manifestation is "the physical embodiment of an expression of a work. As an entity, manifestation represents all the physical objects that bear the same characteristics, in respect to both intellectual content and physical form."[3] The performance the London Philharmonic made of the Ninth in 1996 is a manifestation. It was a physical embodiment even if not recorded, though of course manifestations are most frequently of interest when they are expressed in a persistent form such as a recording or printing. When we say, "The recording of the London Philharmonic's 1996 performance captured the essence of the Ninth," we are generally referring to a manifestation.

- Item is "a single exemplar of a manifestation. The entity defined as item is a concrete entity."[3] Each copy of the 1996 pressings of that 1996 recording is an item. When we say, "Both copies of the London Philharmonic's 1996 performance of the Ninth are checked out of my local library," we are generally referring to items.

Group 1 entities are not strictly hierarchical, because entities do not always inherit properties from other entities.[4] Despite initial positive assessments of FRBR clarifying the thoughts around the conceptual underpinnings of works, there has been later disagreement about what the Group 1 entities actually mean.[5] The distinction between Works and Expressions is also unclear in many cases.

Relationships

[edit]In addition to the relationships between Group 1 and Groups 2 and 3 discussed above, there are many additional relationships covering such things as digitized editions of a work to the original text, and derivative works such as adaptations and parodies, or new texts which are critical evaluations of a pre-existing text.[6] FRBR is built upon relationships between and among entities. "Relationships serve as the vehicle for depicting the link between one entity and another, and thus as the means of assisting the user to ‘navigate’ the universe that is represented in a bibliography, catalogue, or bibliographic database."[7] Examples of relationship types include, but are not limited to:[8]

Equivalence relationships

[edit]Equivalence relationships exist between exact copies of the same manifestation of a work or between an original item and reproductions of it, so long as the intellectual content and authorship are preserved. Examples include reproductions such as copies, issues, facsimiles and reprints, photocopies, and microfilms.

Derivative relationships

[edit]Derivative relationships exist between a bibliographic work and a modification based on the work. Examples include:

- Editions, versions, translations, summaries, abstracts, and digests

- Adaptations that become new works but are based on old works

- Genre changes

- New works based on the style or thematic content of the work

Descriptive relationships

[edit]Descriptive relationships exist between a bibliographic entity and a description, criticism, evaluation, or review of that entity, such as between a work and a book review describing it. Descriptive relationships also includes annotated editions, casebooks, commentaries, and critiques of an existing work.

See also

[edit]- BIBFRAME

- Functional Requirements for Authority Data (FRAD)

- FRSAD

- FRBRoo

- IFLA Library Reference Model

- International Cataloguing Principles (ICP)

- Resource Description and Access (RDA)

- Paris Principles (PP)

References

[edit]- ^ FRBR: FRBR, RDA, and MARC (PDF), Cooperative and Instructional Programs Division, Library of Congress, September 2012, archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021, retrieved 22 August 2021

- ^ https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr/frbr_2008.pdf p.79

- ^ a b c d "Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records - Final Report - Part 1". ifla.org. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Renear, Allen H.; Choi, Yunseon (10 October 2007). "Modeling Our Understanding, Understanding Our Models - The Case of Inheritance in FRBR" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 43 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1002/meet.14504301179.

- ^ Floyd, Ingbert (2009). "Multiple interpretations: Implications of FRBR as a boundary object". Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 46 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1002/meet.2009.14504603110.

- ^ Tillett, Barbara. "What is FRBR?" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records - Final Report - Part 2". ifla.org. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. "Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records: Final Report". Retrieved 3 December 2013.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2011) |

Further reading

[edit]- Karen Coyle, FRBR Before and After, online, CC-BY license. American Library Association, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8389-1364-2

- IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Functional requirements for bibliographic records : final report. — München: K.G. Saur, 1998. — (UBCIM publications; new series, vol. 19). — ISBN 3-598-11382-X. (Accessed Nov. 6, 2005)

- Madison, Olivia M.A. (July 2000). "The IFLA Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records". Library Resources & Technical Services. 3. 44 (3): 153–159. doi:10.5860/lrts.44n3.153. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Tillett, Barbara. FRBR: A Conceptual Model for the Bibliographic Universe. Library of Congress Cataloging Distribution Service, 2004. (Accessed Nov. 6, 2005)

External links

[edit]- RDA: Resource Description and Access

- Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records, International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

- Library of Congress Training for RDA: Resource Description & Access: FRBR: FRBR, RDA, and MARC