Friendship

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Friendship is a relationship of mutual affection between people.[1] It is a stronger form of interpersonal bond than an "acquaintance" or an "association", such as a classmate, neighbor, coworker, or colleague.

In some cultures,[which?] the concept of friendship is restricted to a small number of very deep relationships; in others, such as the U.S. and Canada, a person could have many friends, and perhaps a more intense relationship with one or two people, who may be called good friends or best friends. Other colloquial terms include besties or Best Friends Forever (BFFs). Although there are many forms of friendship, certain features are common to many such bonds, such as choosing to be with one another, enjoying time spent together, and being able to engage in a positive and supportive role to one another.[2]

Sometimes friends are distinguished from family, as in the saying "friends and family", and sometimes from lovers (e.g., "lovers and friends"), although the line is blurred with friends with benefits. Similarly, being in the friend zone describes someone who is restricted from rising from the status of friend to that of lover (see also unrequited love).

Friendship has been studied in academic fields, such as communication, sociology, social psychology, anthropology, and philosophy. Various academic theories of friendship have been proposed, including social exchange theory, equity theory, relational dialectics, and attachment styles.

Developmental psychology

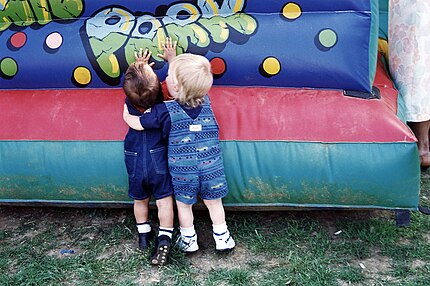

Childhood

The understanding of friendship by children tends to be focused on areas such as common activities, physical proximity, and shared expectations.[3]: 498 [a] Such friendships provide an opportunity for playing and practicing self-regulation.[4]: 246 Most children tend to describe friendship in terms of things like sharing, and children are more likely to share with someone they consider to be a friend.[4]: 246 [5][6]

Recent work on friendship in young children investigated the cues they use to infer friendship. Young children use cues such as sharing resources, like snacks,[7] and sharing secrets,[8] especially in older adolescents, to determine friendship status. When comparing cues of similarity in food preference or gender, propinquity, and loyalty in adolescent children, younger children rely on similarity in gender/food preferences but more so propinquity to infer friendship while older adolescents rely heavily on propinquity to infer friendship.[9]

As children mature, they become more reliant on others, as awareness grows. They gain the ability to empathize with their friends, and enjoy playing in groups. They also experience peer rejection as they move through the middle childhood years. Establishing good friendships at a young age helps a child to be better acclimated in society later on in their life.[5]

Based on the reports of teachers and mothers, 75% of preschool children had at least one friend. This figure rose to 78% through the fifth grade, as measured by co-nomination as friends, and 55% had a mutual best friend.[4]: 247 About 15% of children were found to be chronically friendless, reporting periods of at least six months without mutual friends.[4]: 250

Friendships in childhood can assist in the development of certain skills, such as building empathy and learning different problem-solving techniques.[10] Coaching from parents can help children make friends. Eileen Kennedy-Moore describes three key ingredients of children's friendship formation: (1) openness, (2) similarity, and (3) shared fun.[11] Parents can also help children understand social guidelines they have not learned on their own.[12] Drawing from research by Robert Selman[13] and others, Kennedy-Moore outlines developmental stages in children's friendship, reflecting an increasing capacity to understand others' perspectives: "I Want It My Way", "What's In It For Me?", "By the Rules", "Caring and Sharing", and "Friends Through Thick and Thin."[14]

Adolescence

In adolescence, friendships become "more giving, sharing, frank, supportive, and spontaneous."[15] Adolescents tend to seek out peers who can provide such qualities in a reciprocal relationship, and to avoid peers whose problematic behavior suggests they may not be able to satisfy these needs.[16] Particular personal characteristics and dispositions are also features sought by adolescents, when choosing whom to begin a friendship with.[17] During adolescence, friendship relationships are more based on similar morals and values, loyalty, and shared interests than those of children, whose friendships stem from being in the same vicinity and access to playthings.[4]: 246

A large study of American adolescents determined how their engagement in problematic behavior (such as stealing, fighting, and truancy) was related to their friendships. Findings indicated that adolescents who were less likely to engage in problematic behavior had friends who did well in school, participated in school activities, avoided drinking, and had good mental health. The opposite was true of adolescents who did engage in problematic behavior. Whether adolescents were influenced by their friends to engage in problem behavior depended on how much they were exposed to those friends, and whether they and their friendship groups "fit in" at school.[18]

Friendships formed during post-secondary education last longer than friendships formed earlier.[19] In late adolescence, cross-racial friendships tend to be uncommon, likely due to prejudice and cultural differences.[17]

Adulthood

Friendship in adulthood provides companionship, affection, and emotional support, and contributes positively to mental well-being and improved physical health.[20]: 426

Adults may find it particularly difficult to maintain meaningful friendships in the workplace. "The workplace can crackle with competition, so people learn to hide vulnerabilities and quirks from colleagues. Work friendships often take on a transactional feel; it is difficult to say where networking ends and real friendship begins."[21] Many adults value the financial well-being and security that their job provides more than developing friendships with coworkers.[22]

2,000 American adults surveyed had an average of two close friends, defined as "people they had 'discussed important matters' with in the past six months".[23] Numerous studies with adults suggest that friendships and other supportive relationships enhance self-esteem.[24]

Older adults

Older adults report high levels of personal satisfaction in their friendships as they age, even as the overall number of friends tends to decline. This satisfaction is associated[clarification needed] with an increased ability to accomplish activities of daily living, as well as a reduced decline in cognitive abilities, decreased instances of hospitalization, and better outcomes related to rehabilitation.[20]: 427 The overall number of reported friends in later life may be mediated by[clarification needed] increased lucidity, better speech and vision, and marital status[which?].[25]: 53 A decline in the number of friends an individual has as they become older has been explained by Carstensen's Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, which describes a change in motivation that adults experience when socializing. The theory states that an increase in age is characterized by a shift from information-gathering to emotional regulation; in order to maintain positive emotions, older adults restrict their social groups to those with whom they share an emotional bond.[26] As one review phrased it:

Research within the past four decades has now consistently found that older adults reporting the highest levels of happiness and general well being also report strong, close ties to numerous friends.[27]

As family responsibilities and vocational pressures lessen, friendships become more important. Among the elderly, friendships can provide links to the larger community, serve as a protective factor against depression and loneliness, and compensate for potential losses in social support previously given by family members.[28]: 32–33 Especially for people who cannot go out as often, interactions with friends allow for continued societal interaction. Additionally, older adults in declining health who remain in contact with friends show improved psychological well-being.[29]

Forming and maintaining

Forming and maintaining friendships often requires time and effort.

Friendships are foremost formed by choice, typically on the basis that the parties involved admire each other on an intimate level, and enjoy commonality and socializing.[30]

Given that friendships provide people with many mental, social, and health benefits,[31] people should want to associate with and form lasting relationships with people who can provide the benefits they need. Thus, people have specific friendship preferences for the types of behaviors and traits that are associated with these benefits.[32] Recent work on friendship preferences shows that while there is much overlap between men and women for the traits they prefer in close same-gender friends (e.g., being prioritized over other friends, friends with varied knowledge/skills), there are some differences: women compared to men had greater preference for emotional support, emotional disclosure, and emotional reassurance, while men compared to women had greater preference for friends that offer opportunities for accruing status, boosting their reputation, and will provide physical aid.[33]

Most people underestimate how much other people like them.[34] The liking gap can make it difficult to form friendships.[35]

According to communications professor Jeffery Hall, most friendships involve tacitly agreed-upon expectations in six different areas:[36]

- Positive regard

- The friends genuinely like each other, and are not merely pretending to like each other for the purpose of social climbing or some other desired benefit.[36]

- Self-disclosure

- The friends feel that they can discuss topics of deep personal significance.[36]

- Instrumental aid

- The friends help each other in practical ways.[36] For example, a friend might drive another friend to the airport.

- Similarity

- The friends have similar worldviews.[36] For example, they might have the same culture, class, religion, or life experiences.

- Enjoyment

- The friends believe that it is fun and easy to spend time together.[36]

- Agency

- The friends have valuable information, skills, or resources that they can share with each other.[36] For example, a friend with business connections might know when a desirable job will be available, or a wealthy friend might pay for an expensive experience.

Not all relationships have the same balance of each area. For example, women may prefer friendships that emphasize genuine positive regard and deeper self-disclosure, and men may prefer friendships with a little more agency.[36]

Developmental issues

People with certain types of developmental disorders may struggle to make and maintain friendships. This is especially true of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),[37] autism spectrum disorders,[38] or children with Down syndrome.[39][40]

Health

Studies found that strong social supports improve a person's prospects for good health and longevity. Conversely, loneliness and a lack of social supports are linked to an increased risk of heart disease, viral infections, and cancer, as well as higher mortality rates overall. Researchers termed friendship networks a "behavioral vaccine" that boosts both physical and mental health.[41]

A large body of research links friendship and health, but the precise reasons for the connection remain unclear. Most studies in this area are large prospective studies that follow people over time, and while there may be a correlation between the two variables (friendship and health status), researchers still do not know if there is a cause and effect relationship (such as: good friendships improve health). Theories that attempt to explain this link include that good friends encourage their friends to lead more healthy lifestyles; that good friends encourage their friends to seek help and access services when needed; that good friends enhance their friends' coping skills in dealing with illness and other health problems; and that good friends actually affect physiological pathways that are protective of health.[42]

Mental health

Having few or no friends is a common experience among those who are diagnosed with a range of mental disorders, and can be used as a telling factor.[16] A 2004 study from the American Journal of Public Health observed that lack of friendship plays a role in increasing risk of suicidal ideation among female adolescents, while also true for having more friends who are not themselves friends with one another. However, it is also suggested that no similar effect is observed for males.[43]

Higher friendship quality directly contributes to self-esteem, self-confidence, and social development.[24] A World Happiness Database study found that people with close friendships are happier, although the absolute number of friends did not increase happiness.[44] Other studies suggested that children who have friendships of a high quality may be protected against the development of certain disorders, such as anxiety and depression.[45] Conversely, having few friends is associated with dropping out of school, as well as aggression, adult crime, and loneliness.[3]: 500 Peer rejection[clarification needed] is also associated with lower later aspiration in the workforce and participation in social activities, while higher levels of friendship were associated with higher adult self-esteem.[3]: 500–01

Having more close friends is correlated with improved mental health and cognitive ability. However, this association stops once around five friends is reached, after which having more friends is no longer linked to better mental health and is correlated with lower cognition. Additionally, people with few or many[compared to?] friends had more symptoms of Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and were less able to learn from their experiences.[46]

Dissolution

Friendships may end. This is often the result of natural changes over time, as friends grow more distant both physically and emotionally, but it can also be the result of a sudden shock, such as learning that a friend holds incompatible values.[36]

Some social media influencers provide suggestions using therapy speak to break up with a friend.[47][48] These have been criticized for being impersonal and upsetting, partially because they often reduce a conversation to a 30-second soundbite-sized announcement.[47][48] Social media posts may also encourage confrontations akin to a workplace performance appraisal, in which one person tells a friend that they are dissatisfied and threatens to break off the relationship if the friend does not conform to their expectations.[36] The end of a friendship is often due to inappropriate expectations on the part of the dissatisfied person, and demanding that a friend meet those expectations is incompatible with friendship's voluntary qualities.[36] Another option would be for the dissatisfied person to look for another friend who can meet the unmet need.[36] For example, if someone is dissatisfied because a friend does not plan events, then that person could find a second friend, someone who enjoys planning events, instead of rejecting the first friend for not being able to single-handedly meet all of their needs.[36]

The dissolution of a friendship may be taken personally as a rejection. Disruptions of friendships are associated with increased guilt, anger, and depression, and may be highly stressful events, especially in childhood. However, potential negative effects can be mitigated if the dissolution of a friendship is replaced with another close relationship.[4]: 248

Demographics

Friends tend to be similar to one another in terms of age, gender, behavior, substance abuse, personal disposition, and academic performance.[4]: 248 [20]: 426 [27]: 55–56 In ethnically diverse countries, children and adolescents tend to form friendships with others of the same race or ethnicity, beginning in preschool, and peaking in middle or late childhood.[4]: 264 As a result of social separation and confinement[clarification needed] of the sexes, friendships between men and women have little presence in recorded history, having only become a widely accepted practice in the 20th century.[49]

Gender differences

In general, girl-girl friendship interactions among children tend to focus on interpersonal connections and mutual support. In contrast, boy-boy interaction tends to be more focused on social status, and may discourage the expression of emotional needs.[50] Girls report more anxiety, jealousy, and relational victimization and less stability related to their friendships. Boys, on the other hand, report higher levels of physical victimization. Nevertheless, boys and girls tend to report relative[compared to?] satisfaction levels with their friendships.[4]: 249–50

Women tend to be more expressive and intimate in their same-sex friendships and have fewer friends.[17] Men are more likely to define intimacy in terms of shared physical experiences. In contrast, women are more likely to define it in terms of shared emotional ones. Men are less likely to make emotional or personal disclosures to other men because the other man could use this information against them. However, they will disclose this information to women (as they are not in competition with them), and men tend to regard friendships with women as more meaningful, intimate, and pleasant. Male-male friendships are generally more like alliances, while female-female friendships are much more attachment-based. This also means that the end of male-male friendships tends to be less emotionally upsetting than that of female-female friendships.[51]

Women tend to be more socially adept than their male peers, among older adults. As a result, many older men may rely upon a female companion, such as a spouse, to compensate for their comparative lack of social skills.[27]: 55 One study found that women in Europe and North America were slightly more likely than men to self-report having a best friend.[52]

Culture

Which relationships count as a true friend, rather than as an acquaintance or a co-worker, vary by culture. In English-speaking cultures, it is not unusual for people to include weaker relationships as being friends.[53] In other cultures, such as the Russian and Polish cultures, only the most significant relationships are considered friends. A Russian might have one or two friends plus a large number of "pals" or acquaintances; a Canadian in similar circumstances might count all of these relationships as being friends.[53]

In Western cultures, friendships are often seen as lesser to familial or romantic relationships.[54] Friendships in Ancient Greece were more utilitarian than affectionate, being based upon obligation and reliance, though different Classical communities understood friendship in different ways, and the Greeks held a much broader conception of friendship than modern English-speaking cultures do.[55][56] Aristotle wrote of there being three kinds of friendships: those in recognition of pleasure, those in recognition of advantage, and those in recognition of virtue.[56]

When discussing taboos of friendship[example needed] it was found that Chinese respondents found more than their British counterparts.[17][ambiguous]

Evolutionary approach

Evolutionary approaches to understanding friendship focus primarily on its function. In other words, what does friendship do for individuals, how does it work psychologically, and how do these processes affect people's actual behavior. Within this field, there are multiple proposed theories or perspectives about the function of forming friendships and making friends. One is the theory of Reciprocal Altruism which provides an explanation as to why individuals make friends with un-related others. It argues that friendship allows people to exchange benefits with each other and keep track of these exchanges in order to avoid exchanging benefits with a poor cooperator, or someone who will take benefits without giving any in return.[57] Another perspective likens friendships to insurance investments and argues when deciding to invest into forming a new friendship with another person an individual should be able to discern: whether the potential friend will be willing to help them back in the future, if the potential friend is in the position to help them in the future, and if the friendship is worth continuing or not, especially when many other potential friendships can be made.[58] These factors will determine whether forming a friendship with someone will be beneficial or injurious. Another explanation for the function of friendships is called the Alliance Hypothesis[59] which argues that the function of friendships is to acquire alliances for future conflicts or disputes. The Alliance Hypothesis states that conflicts typically can be won if and only if one side is able to acquire more allies than the competing side, all else equal, so individuals should be able to increase their odds of winning the conflict if they are able to recruit more alliances to their side.[59] Choosing your allies can be very important and there exists a variety of methods in deciding allies such as bandwagoning or choosing an ally that is loyal and will come to your aid in the future conflicts.[60] Thus, individuals should form alliances (i.e., friendships) with people that ranks themselves higher than other allies/friends. It is relative rank (i.e., where the self ranks among all other individuals) that is the most important contributing factor when deciding who is a loyal ally and friend.[60]

Friendship jealousy

Jealousy is an emotion that is often studied in the context of romantic and sexual relationships. However, individuals also feel jealous when it comes to potentially losing valued friendships. Friendship jealousy acts as an alert to the self that a close friends' other friends may be a threat to the self's relationship with that close friend[60] which motivates the self to enact behaviors that prevent the close friend from further developing better relationships with their other friends.[32] A recent multi-study paper found that friendship jealousy is activated by the potential loss of a friend by another person, is highly attuned to the feeling or thoughts of being replaced, and that the closer or more valued that friendship is, the more friendship jealousy someone will feel.[61] Men and women also tend to express different levels of friendship jealousy depending on the person who is attempting to replace them in the friendship, such that women compared to men expressed more jealousy over the potential loss of a best-friend to another woman.[62]

Non-human friendship

Friendship is found among animals of higher intelligence, such as higher mammals and some birds. There is ample comparative animal research on the existence of friendships, or the existence of similar forms of relationships, in animals. The function of these relationships in non-human animals appears to primarily be for forming and solidifying alliances for a wide range of fitness and survival reasons.[63] Across a range of non-human animal species, alliances are formed for protection,[63] competition over reproductive access to receptive mates,[64] as means to seek social comfort,[65] solidify social bonds,[66] and to thwart diseases.[67] An expansive meta-analysis examining grooming behaviors in 14 different primate species found that grooming behaviors elicit different types of benefit exchanges, such as support and aid for future intra-species conflicts.[68] Male bottlenose dolphins use synchronous surfacing to determine membership of other potential male allies[69] while female bottlenose dolphins use gentle contact behaviors (i.e., touching behaviors) with other females in response to harassment from males.[70] Female spotted hyenas, whose groups follow a very strict dominance hierarchy, form alliances (i.e., coalitionary bonds) to move up the dominance hierarchy by usurping a hyena of higher dominance rank.[71] Feral female horses develop alliances with other female horses to avoid harassment from male horses and these alliances aid in increasing their offspring's chances of survival.[72]

See also

- Blood brother

- Boston marriage

- Bromance

- Casual relationship

- Cross-sex friendships

- Female bonding

- Fraternization

- Frenemy

- Friend of a friend

- Friendship Day

- Imaginary friend

- Intimate relationship

- Kalyāṇa-mittatā (spiritual friendship)

- Male bonding

- Nicomachean Ethics, Books VIII and IX: Friendship and partnership

- Platonic love

- Prosocial behavior

- Romantic friendship

- Sharing

- Social connection

- Theorem on friends and strangers

- Womance

Notes

References

- ^ "Definition for friend". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford Dictionary Press. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Howes, Carollee (1983). "Patterns of Friendship". Child Development. 54 (4): 1041–1053. doi:10.2307/1129908. ISSN 0009-3920. JSTOR 1129908.

- ^ a b c d Bremner, J. Gavin (2017). An Introduction to Developmental Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-8652-0. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zelazo, Philip David (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology. Vol. 2: Self and Other. OUP US. ISBN 978-0-19-995847-4. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ a b Newman, Barbara M.; Newman, Phillip R. (2012). Development Through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. Stanford, Conn.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lafata, Alexia (17 Jun 2015). "Your Childhood Friendships Are The Best Friendships You'll Ever Have". Elite Daily. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ DeJesus, Jasmine M.; Rhodes, Marjorie; Kinzler, Katherine D. (2013-10-07). "Evaluations Versus Expectations: Children's Divergent Beliefs About Resource Distribution". Cognitive Science. 38 (1): 178–193. doi:10.1111/cogs.12093. ISSN 0364-0213. PMID 24117730. S2CID 8358667.

- ^ Liberman, Zoe; Shaw, Alex (November 2018). "Secret to friendship: Children make inferences about friendship based on secret sharing". Developmental Psychology. 54 (11): 2139–2151. doi:10.1037/dev0000603. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 30284884. S2CID 52914199.

- ^ Liberman, Zoe; Shaw, Alex (August 2019). "Children use similarity, propinquity, and loyalty to predict which people are friends". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 184: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2019.03.002. ISSN 0022-0965. PMID 30974289. S2CID 109941102.

- ^ Kennedy-Moore, Eileen (2013). "What Friends Teach Children". Psychology Today.

- ^ Kennedy-Moore, Eileen (2012). "How children make friends (part 1)". Psychology Today. (part 2) (part3)

- ^ Elman, N.M.; Kennedy-Moore, E. (2003). The Unwritten Rules of Friendship: Simple Strategies to Help Your Child Make Friends. New York: Little, Brown.

- ^ Selman, R.L. (1980). The Growth of Interpersonal Understanding: Developmental and Clinical Analyses. New York: Academic Press.

- ^ Kennedy-Moore, Eileen (26 February 2012). "Children's Growing Friendships". Psychology Today.

- ^ "Friendships — Tuituia domain". practice.orangatamariki.govt.nz. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ a b Reisman, John M. (September 1, 1985). "Friendship and its Implications for Mental Health or Social Competence". The Journal of Early Adolescence. 5 (3): 383–91. doi:10.1177/0272431685053010. S2CID 144275803.

- ^ a b c d Verkuyten, Maykel; Masson, Kees (1996-10-01). "Culture and Gender Differences in the Perception of Friendship by Adolescents". International Journal of Psychology. 31 (5): 207–217. doi:10.1080/002075996401089. ISSN 0020-7594.

- ^ Crosnoe, Robert; Needham, Belinda (2004). "Holism, contextual variability, and the study of friendships in adolescent development". Child Development. 75 (1): 264–279. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00668.x. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 15015689.

- ^ Sparks, Glenn (August 7, 2007). "Study shows what makes college buddies lifelong friends". Purdue University News. Archived from the original on 2019-04-07.

- ^ a b c Schulz, Richard (2006). The Encyclopedia of Aging: Fourth Edition, 2-Volume Set. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8261-4844-5. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Williams, Alex (13 July 2012). "Friends of a Certain Age: Why Is It Hard To Make Friends Over 30?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ Bryant, Susan. "Workplace Friendships: Asset or Liability?". Monster.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ Willis, Amy (November 8, 2011). "Most adults have 'only two close friends'". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- Brashears, Matthew E. (2011). "Small networks and high isolation? A reexamination of American discussion networks". Social Networks. 33 (4). Elsevier BV: 331–341. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2011.10.003. ISSN 0378-8733.

- ^ a b Berndt, Thomas J. (2002). "Friendship Quality and Social Development" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 11. American Psychological Society: 7–10. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00157. S2CID 14785379.

- ^ Blieszner, Rosemary; Adams, Rebecca G. (1992). Adult Friendship. Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-3673-7. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Carstensen, L.L. (1993). "Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity". In Jacobs, J.E. (ed.). Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 209–254.

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. (1999). "Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity". American Psychologist. 54 (3): 165–181. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165. PMID 10199217.

- Carstensen, L.L.; Gottman, J.M.; Levensen, R.W. (1995). "Emotional behavior in long-term marriage". Psychology and Aging. 10 (1): 140–149. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.10.1.140. PMID 7779311.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Jon F.; Federowicz, Molly; Nussbaum, Paul D. (2010). Brain Health and Optimal Engagement for Older Adults. Editorial Aresta S.C. ISBN 978-84-937440-0-7. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Burleson, Brant R. (2012). Communication Yearbook 19. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87317-8. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Berk, Laura E. (2014). Exploring Lifespan Development (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-205-95738-5.

- ^ Spencer, Liz; Pahl, Ray (2007). Rethinking Friendship: Hidden Solidarities Today. Princeton University Press. p. 59. doi:10.1515/9780691188201. ISBN 978-0-691-18820-1.

- ^ Dunbar, R.I.M. (January 2018). "The Anatomy of Friendship". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 22 (1): 32–51. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2017.10.004. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 29273112. S2CID 31147785.

- ^ a b Tooby, J; Cosmides, Leda (1996). Friendship and the banker's paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Williams, Keelah E.G.; Krems, Jaimie Arona; Ayers, Jessica D.; Rankin, Ashley M. (January 2022). "Sex differences in friendship preferences". Evolution and Human Behavior. 43 (1): 44–52. Bibcode:2022EHumB..43...44W. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.09.003. ISSN 1090-5138. S2CID 244009099.

- ^ Boothby, Erica J.; Cooney, Gus; Sandstrom, Gillian M.; Clark, Margaret S. (2018). "The Liking Gap in Conversations: Do People Like Us More Than We Think?". SAGE Journals. Vol. 29, no. 11. pp. 1742–1756. doi:10.1177/0956797618783714.

- Ducharme, Jamie (2018-09-17). "People Like You More Than You Think, a New Study Suggests". Time.

- ^ Reinberg, Steven (2018-09-19). "'Liking Gap' Might Stand in Way of New Friendships". US News.

- Society for Personality and Social Psychology (2019-02-08). "Bridging the 'liking-gap,' researchers discuss awkwardness of conversations". Science Daily.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Khazan, Olga (2023-06-28). "Stop Firing Your Friends". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ Wiener, Judith; Schneider, Barry H. (2002). "A multisource exploration of the friendship patterns of children with and without learning disabilities". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 30 (2): 127–41. doi:10.1023/A:1014701215315. PMID 12002394. S2CID 42157217. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Hoza, Betsy (June 7, 2007). "Peer Functioning in Children With ADHD". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 32 (6): 101–06. doi:10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.011. PMC 2572031. PMID 17261489.

- ^ Bauminger, Nirit; Solomon, Marjorie; Aviezer, Anat; Heung, Kelly; Gazit, Lilach; Brown, John; Rogers, Sally J. (3 January 2008). "Children with Autism and Their Friends: A Multidimensional Study of Friendship in High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 36 (2): 135–50. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x. PMID 18172754. S2CID 35579739.

- ^ "Friendships & Social Relationships". National Down Syndrome Society.

- ^ Buckley, Sue; Bird, Gillian; Sacks, Ben (2002). Social Development for Individuals with Down Syndrome – An Overview. Down Syndrome Educational Trust. ISBN 9781903806210.

- ^ Sias, Patricia; Bartoo, Heidi (2007). "Friendship, Social Support, and Health". In L'Abate, Luciano (ed.). Low-Cost Approaches to Promote Physical and Mental Health: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 455–472. ISBN 978-0-387-36898-6.

- ^ Jorm, Anthony F. (2005). "Social networks and health: it's time for an intervention trial". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 59 (7): 537–538. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.031559. ISSN 0143-005X. PMC 1757066. PMID 15965132.

- ^ "Friendships play key role in suicidal thoughts of girls, but not boys". EurekAlert!. Ohio State University. January 6, 2004. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Bearman, Peter S.; Moody, James (2004). "Suicide and Friendships Among American Adolescents". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (1): 89–95. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.1.89. PMC 1449832. PMID 14713704.

- ^ Harter, Pascale (1 July 2013). "Can we make ourselves happier?". BBC News.

- ^ Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F.; Bukowski, W.M.; Dionne, G.; Tremblay, R.E.; Boivin, M. (2013). "Can friends protect genetically vulnerable children from depression?". Development and Psychopathology. 25 (2): 277–89. doi:10.1017/s0954579412001058. PMID 23627944. S2CID 12110401.

- Bukowski, W.M.; Hoza, B.; Boivin, M. (1994). "Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: the development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 11 (3): 471–84. doi:10.1177/0265407594113011. S2CID 143806076.

- ^ Shen, Chun; Rolls, Edmund T; Xiang, Shitong; Langley, Christelle; Sahakian, Barbara J; Cheng, Wei; Feng, Jianfeng (2023-07-03). Whelan, Robert; Büchel, Christian; Whelan, Robert; Schreuders, Lisa (eds.). "Brain and molecular mechanisms underlying the nonlinear association between close friendships, mental health, and cognition in children". eLife. 12: e84072. doi:10.7554/eLife.84072. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 10317501. PMID 37399053.

- "Is more always better?". eLife. 2023-07-03. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ a b Mehta, Jonaki; Jarenwattananon, Patrick; Limbong, Andrew (13 April 2023). "'Therapy speak' is everywhere, but it may make us less empathetic". All Things Considered. NPR.

- ^ a b Walters, Meg. "Is Therapy-Speak Ruining Our Relationships?". Refinery 29. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ Deresiewicz, William (2007). "Thomas Hardy and the History of Friendship Between the Sexes". The Wordsworth Circle. 38 (1–2): 56–63. doi:10.1086/TWC24043958. ISSN 0043-8006. S2CID 165725516.

- ^ Harris, Margaret (2002). Developmental Psychology: A Student's Handbook. Taylor & Francis. pp. 320–02. ISBN 978-1-84169-192-3. Retrieved 26 September 2017.[clarification needed]

- ^ Campbell, Anne (2013-05-16). A Mind Of Her Own: The evolutionary psychology of women. OUP Oxford. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-0-19-164701-7.

- David-Barrett, Tamas; Rotkirch, Anna; Carney, James; Behncke Izquierdo, Isabel; Krems, Jaimie A.; Townley, Dylan; McDaniell, Elinor; Byrne-Smith, Anna; Dunbar, Robin I. M. (2015-03-16). Jiang, Luo-Luo (ed.). "Women Favour Dyadic Relationships, but Men Prefer Clubs: Cross-Cultural Evidence from Social Networking". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118329. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018329D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118329. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4361571. PMID 25775258.

- ^ Pearce, Eiluned; Machin, Anna; Dunbar, Robin I. M. (18 October 2020). "Sex Differences in Intimacy Levels in Best Friendships and Romantic Partnerships". Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology. 7 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1–16. doi:10.1007/s40750-020-00155-z. ISSN 2198-7335. S2CID 226358247.

- Heingartner, Douglas, ed. (2020-10-20). "Women are more likely than men to say they have a best friend". PsychNewsDaily. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ a b Doucerain, Marina M.; Ryder, Andrew G.; Amiot, Catherine E. (October 2021). "What Are Friends for in Russia Versus Canada?: An Approach for Documenting Cross-Cultural Differences". Cross-Cultural Research. 55 (4): 382–409. doi:10.1177/10693971211024599. ISSN 1069-3971. S2CID 236265614.

- ^ Tillmann-Healy, Lisa M. (2003-10-01). "Friendship as Method". Qualitative Inquiry. 9 (5): 729–749. doi:10.1177/1077800403254894. ISSN 1077-8004. S2CID 144256070.

- ^ Konstan, David (1997). Friendship in the Classical World. Key Themes in Ancient History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 2. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511612152. ISBN 978-0-521-45402-5.

- ^ a b Cooper, John M. (1977). "Aristotle on the Forms of Friendship". The Review of Metaphysics. 30 (4): 619–648. ISSN 0034-6632. JSTOR 20126987.

- ^ Trivers, Robert L. (March 1971). "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (1): 35–57. doi:10.1086/406755. ISSN 0033-5770.

- ^ Burkett, Brandy; Cosmides, Leda; Bugental, Daphne (2007). "Jealousy, friendship, and the banker's paradox". PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e514412014-554. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ a b DeScioli, Peter; Kurzban, Robert (2009-06-03). "The Alliance Hypothesis for Human Friendship". PLOS ONE. 4 (6): e5802. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5802D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005802. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2688027. PMID 19492066.

- ^ a b c DeScioli, Peter; Kurzban, Robert; Koch, Elizabeth N.; Liben-Nowell, David (January 2011). "Best Friends". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (1): 6–8. doi:10.1177/1745691610393979. ISSN 1745-6916. PMID 26162107. S2CID 212547.

- ^ Krems, Jaimie; Williams, Keelah; Kenrick, Douglas; Aktipis, Athena (2020-04-28). "Friendship jealousy: One tool for maintaining friendships in the face of third-party threats?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 120 (4): 977–1012. doi:10.31234/osf.io/wdc2q. PMID 32772531. S2CID 221101011. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ Krems, Jaimie Arona; Williams, Keelah E.G.; Merrie, Laureon A.; Kenrick, Douglas T.; Aktipis, Athena (March 2022). "Sex (similarities and) differences in friendship jealousy". Evolution and Human Behavior. 43 (2): 97–106. Bibcode:2022EHumB..43...97K. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.11.005. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ^ a b Hemelrijk, Charlotte K.; Steinhauser, Jutta (2007), "15 Cooperation, Coalition, and Alliances", Handbook of Paleoanthropology, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 1321–1346, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_43, ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4, retrieved 2023-11-26

- ^ Hemelrijk, Charlotte K.; Luteijn, Madelein (1998-03-23). "Philopatry, male presence and grooming reciprocation among female primates: a comparative perspective". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 42 (3): 207–215. Bibcode:1998BEcoS..42..207H. doi:10.1007/s002650050432. ISSN 0340-5443. S2CID 43297085.

- ^ Shutt, Kathryn; MacLarnon, Ann; Heistermann, Michael; Semple, Stuart (2007-02-27). "Grooming in Barbary macaques: better to give than to receive?". Biology Letters. 3 (3): 231–233. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0052. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2464693. PMID 17327200.

- ^ Silk, Joan B. (October 2002). "The Form and Function of Reconciliation in Primates". Annual Review of Anthropology. 31 (1): 21–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.032902.101743. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ Zamma, Koichiro (March 2002). "Grooming site preferences determined by lice infection among Japanese macaques in Arashiyama". Primates. 43 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1007/bf02629575. ISSN 0032-8332. PMID 12091746. S2CID 42457072.

- ^ Schino, Gabriele (2006-10-03). "Grooming and agonistic support: a meta-analysis of primate reciprocal altruism". Behavioral Ecology. 18 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1093/beheco/arl045. hdl:10.1093/beheco/arl045. ISSN 1465-7279.

- ^ Connor, Richard C.; Smolker, Rachel; Bejder, Lars (December 2006). "Synchrony, social behaviour and alliance affiliation in Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops aduncus". Animal Behaviour. 72 (6): 1371–1378. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.03.014. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 4513557.

- ^ Connor, Richard; Mann, Janet; Watson-Capps, Jana (2006-06-09). "A Sex-Specific Affiliative Contact Behavior in Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins, Tursiops sp". Ethology. 112 (7): 631–638. Bibcode:2006Ethol.112..631C. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01203.x. ISSN 0179-1613.

- ^ Strauss, Eli D.; Holekamp, Kay E. (2019-03-11). "Social alliances improve rank and fitness in convention-based societies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (18): 8919–8924. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.8919S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810384116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6500164. PMID 30858321.

- ^ Cameron, Elissa Z.; Setsaas, Trine H.; Linklater, Wayne L. (2009-08-18). "Social bonds between unrelated females increase reproductive success in feral horses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (33): 13850–13853. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613850C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900639106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2728983. PMID 19667179.

Further reading

- Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics. VIII & IX.

- Bray, Alan (2003). The Friend. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07181-7.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Laelius de Amicitia.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1841). "Friendship". Essays: First Series. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Hare, Brian; Woods, Vanessa (August 2020). "Survival of the Friendliest: Natural selection for hypersocial traits enabled Earth's apex species to best Neandertals and other competitors". Scientific American. 323 (2): 58–63.

- Lepp, Ignace (1966). The Ways of Friendship. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Said, Edward (1979). Orientalism. US: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-74067-6.

- Terrell, John Edward (2014). A Talent for Friendship: Rediscovery of a Remarkable Trait. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199386451.

External links

- BBC Radio 4 series "In Our Time", on Friendship, 2 March 2006

- Friendship at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy