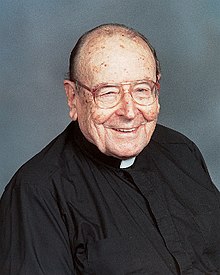

Eugene Boyle

The Reverend Monsignor Eugen Boyle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 15 June 1946 by John Joseph Mitty |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 28, 1921 San Francisco, California, United States of America |

| Died | May 24, 2016 (aged 94) Palo Alto, California, United States of America |

| Occupation | Catholic Priest |

Eugene Boyle (July 28, 1921 – May 24, 2016) was an American Catholic priest and activist based in California. He became known in the 1960s and 1970s for supporting the Civil Rights Movement as well as left-wing political groups such as the United Farm Workers and the Black Panther Party. He was the first Catholic clergyman to run for the legislature in California history, despite opposition from within the Catholic hierarchy.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Eugene was born in San Francisco on July 28, 1921. He attended Saint John's School in San Francisco, Saint Joseph's College Seminary in Mountain View and Saint Patrick's Seminary in Menlo Park, and was ordained by Archbishop John J. Mitty on June 15, 1946.

Early priesthood

[edit]After ordination, Boyle served in parishes in San Francisco and Livermore, eventually becoming Pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in San Francisco by the late 1960s. In 1956, he became the host of his own radio show on KCBS, entitled "Underscore: Catholic Views in Review", described as "an adult show voicing the dialogue of religion and modern life" and discussed topics such as church-state relations, the Civil Rights Movement and Social Justice. The show lead to Boyle gaining the reputation of "San Francisco's leading liberal Catholic intellectual".[2]

Civil Rights Movement

[edit]Boyle became politically active, as many priests in that time were, after being influenced by the Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s, which encouraged Catholics to actively engage themselves in the world.[2]

In 1962, Boyle was recruited to become Chaplain of the Archdiocese of San Francisco's "Catholic Interracial Council", a group dedicated to promoting harmony between the black and white communities in San Francisco. The work of the CIC was considered important and contemporary by the Church in the 1960s; beyond the national debate that had emerged from the Civil Rights Movement, the Black population of San Francisco had risen from just 4,846 around 1940 to a considerable 74,000 in 1960.[3] With this sudden increase in population, racial tensions had risen in the area.

The work of the CIC brought Boyle into the Civil Rights movement itself, although he admitted himself that he was reluctant to do so at first out of the shame of breaking social norms in America;

Though I was becoming intellectually aware and sympathetic to the cause to the purposes of the heightening civil right struggle, I was viscerally repulsed by many of the tactics employed, the street marches, the demonstrations, the sit-ins,...Somehow, I was convinced cool-headed reason would prevail: Surely knowledge, understanding, rational discourse, were sufficient to persuade people of this freedom loving country to change its law

— Eugene Boyle[4]

Boyle's involvement in the Civil Rights Movement saw him march with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 at a protest around San Francisco City Hall, in response to Civil Rights leaders including King being targeted by a bomb while staying at a hotel in Alabama.[5]

I recall distinctly how embarrassed I was feeling doing this because this was the thing you were just not brought up to do...even when you are standing up for people's rights, and for the poor, and for justice...there would be a sense that you were not doing the work you were ordained to do as a priest

— Eugene Boyle[4]

However, as Boyle was further pulled into interracial dialogue and public life, the more comfortable he became with it. Along with the CIC, He campaigned for "fair housing" in San Francisco, working to fight the § Rumford Fair Housing Act, which allowed white real estate sellers to discriminated against "coloured" people. Boyle was able to rally the Catholic Bishops of San Francisco against the proposed law, who then came out and vocally condemned it, but despite these efforts, it was still voted into law.[6] While the Bill was later ruled unconstitutional, Boyle was highly disappointed by the public, feeling that the bill was clearly immoral.

Despite losing the vote, Boyle was still spurred to fight for civil rights. The campaign against the Fair Housing Act had seen him made chairperson of the newly established San Francisco Archdiocesan Commission on Social Justice, further augmenting his authority to speak and tackle social justice issues in San Francisco. Furthermore, the campaign had also brought together a coalition of various religious group from around the city that Boyle could harness to fight for civil rights.

The Little Kerner Report

[edit]In 1965, Boyle joined Martin Luther King Jr.'s campaign in Selma, Alabama for the Selma to Montgomery marches. That same year he also joined up with Cesar Chavez on a protest march from Delano to Sacramento, which was the beginnings of the Delano grape strike. In the years to come Boyle would become an important ally to Chavez and the United Farm Workers labour movement.

In 1968 and 1969 Boyle would face back-to-back controversies that would see him pitted in arguments against his superiors in the Catholic hierarchy. The first controversy was the "little Kerner Report". 1968 the Kerner Commission published a report on the cause of the riots of the Long, hot summer of 1967. It concluded that racism was the ultimate cause of the riots. The report caused enormous controversy across the United States of America for the starkness of the language used to express its findings. In the wake of the findings of the Kerner Report, the San Francisco Conference on Race, Religion, and Social Concerns (SFCRRSC) asked Boyle and seminaries working under him to create a report in a similar vein, examining the conditions of the Black Community in San Francisco. What Boyle had intended to be a 40-page report became a 600-page titan entitled "San Francisco: City in Crisis" and became nicknamed the "Little Kerner Report". In its findings, the report contained not just criticism of the wider white power structure in San Francisco, but also levelled criticism against Churches and Synagogues in San Francisco. The SFCRRSC lead a press conference to announce the publishing of the report and report became front-page news in the City and caused massive controversy.[7]

Despite praising his effort, San Francisco Major Joseph Alioto denounced the report, calling it "inflammatory and ill-conceived". What partially alarmed and infuriated the establishment in San Francisco was that the report suggested a race riot could be imminent in the city.

Archbishop Joseph Thomas McGucken, Boyle's direct religious superior, publicly supported the report when it was published. However, two months after the report came out, Boyle was moved to a new, predominantly African-American parish. Then the following year McGucken cancelled Boyle's yearly seminar, privately fearing the seminarians were becoming too political.

Black Panther Party

[edit]Boyle's new parish was roughly in the Western Addition neighbourhood of San Francisco, which was predominantly African-American. Through working and engaging with the community, Boyle came into contact with the Black Panther Party, who had originated just over the Bay Bridge in Oakland. Boyle seemed to be aware of the controversy around Panthers but believed they had been misrepresented in the press. What primarily interested Boyle was the Panthers' social works, such as their free Breakfast for Children Programme, in which members of the Party would provide food for underprivileged children before the school day started. Boyle also believed that isolating a movement such as the Panthers would only further back them into a corner.[8]

It was with Boyle's permission that the Black Panthers set up their Free Breakfast programme at Sacred Heart School in the Parish. It was not until many months later that Sacred Heart and Boyle would be swept up with the Panthers in the Black Panther Coloring Book Scandal.

In 1968 San Francisco Police Officer Ben Lashkoff appeared before a Senate Committee and stated that he had discovered a Black Panther Coloring book, aimed at the children who came for breakfast, which encouraged them to commit violence against the police. Lashkoff contended that Boyle was aware of the book, and allowed it to be distributed at Sacred Heart. The news story became front-page news in San Francisco and once again the establishment looked in fury towards Boyle. Boyle fully stood by the Panthers, refusing to end the Breakfast programme and declared that at most 2 books had ever been handed out, and once he was made aware of the book he had immediately forbid it. Boyle also claimed no more than 25 copies of the book could ever have been created. Finally, he declared the book was highly suspect to begin with, as it did not reflect the views of the Black Panthers.[9]

Boyle's stern defence of the Panthers was met with outrage from the white public, who demanded his resignation. Archbishop McGucken was put under considerable pressure to censure Boyle. However, despite his own feelings on the matter, McGucken refused to do so.

It was only years later in 1975 that Boyle, The Panthers and the American Public at large became aware of COINTELPRO, a dedicated unit of the FBI that had been directed by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to destroy the Black Panther's reputation by smearing their name in any way possible. It has been suggested that the "Black Panther Coloring Book" was a deliberate invention of the FBI designed to turn the white community against the Black Panthers.[9][10]

Archbishop McGucken

[edit]In the wake of the Little Kerner Report and the Coloring Book affair, yet more controversy would be in store for Fr. Boyle and Archbishop McGurken. In an attempt to pull back from politics, McGucken decided that he would not give his permission for Boyle to run his seminar as he had done in 1968, looking to avoid any repeat of the Little Kerner Report. However, when supporters of Boyle became aware of this, the reaction was quite aggravated. The Monitor, a local newspaper in San Francisco sympathetic to Boyle, lead with the headline " le fired from College post". The narrative that McGurken had fired Boyle based on his social views emerged in many quarters and this drew negative commentary. The pressure built up so much it boiled over into the Archbishop being confronted by a community group of 150 people headed up by a local Black Methodist pastor, Rev. Cecil Williams, on the steps of his own Chancery building, demanding that the Archbishop explain himself. Archbishop McGucken suggested he had not fired Boyle because of his social views, nor was it because of personal animosity. The crowd, however, was not pleased with this explanation and heckled and jeered the Archbishop. Shaken by the confrontation, McGucken agreed to put his actions up for review by the San Francisco Priest's Senate, promising to stand by their decision on the matter. The move made national headlines as it was almost unprecedented for a Catholic Archbishop to allow a challenge to his authority of this sort or to cede his authority in this way. As there was no precedent in Canon law for a process of this nature, it took some time for things to progress.[11]

In December 1969, the committee responsible for reviewing McGucken came to their conclusion. They used language so ambiguous in meaning that the San Francisco Chronicle announced the committee had found in favour of Boyle, while the San Francisco Examiner proclaimed "Priests vindicate SF Archbishop". The committee found that McGucken had not acted on racial bias, citing his good works in favour of interracial community relations, but that Boyle could be reinstated to the Seminary following discussion with McGucken.[12]

Later years

[edit]1973, Boyle became Director of Field Education at the Jesuit School of Theology at the University of Berkley. In 1974, Boyle ran for California State Assembly, seeking to represent the 16th district, located in San Francisco. Despite a chronic lack of funding, Boyle was able to secure 45% of the vote.[12]

For the rest of his life and career, Boyle remained in projects based around Social Justice, although never again courted the controversy he earned during the 60s and 70s.

In 2000, Pope John Paul II approved giving Boyle the honorary title of monsignor.[13]

Monsignor Boyle died in 2016.

References

[edit]- ^ Nolte, Carl (3 June 2016). "Monsignor Eugene Boyle, maverick priest of '60 and '70s, dies". Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ a b Burns, Jeffrey M (1995). "Eugene Boyle, the Black Panther Party and the New Clerical Activism". U.S. Catholic Historian. 13 (3): 137–158. JSTOR 25154518.

- ^ Burns (1995), Page 4

- ^ a b Burns (1995), Page 5

- ^ Issel, William; Wold, Mary Anne (Fall 2008). "Catholics and the Campaign for Racial Justice in San Francisco From Pearl Harbor to Proposition 14". American Catholic Studies. 119 (3): 21–43 (. JSTOR 44195086.

- ^ Burns (1995), Page 8

- ^ Burns (1995), Page 10, 11

- ^ Burns (1995), Page 15

- ^ a b Burns (1995), Page 17

- ^ Clay Mansfield, O. (2019). On Story Ground: The Catholic Interracial Council in the Archdiocese of San Francisco. PhD. University of Virginia.

- ^ Burns (1995), Page 20

- ^ a b Burns (1995), Page 21

- ^ Kinney, Aaron (31 May 2016). "Palo Alto: Hundreds pay respects to late priest Eugene Boyle". East Bay Times. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- 1921 births

- 2016 deaths

- 20th-century American Roman Catholic priests

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American civil rights activists

- Catholics from California

- COINTELPRO targets

- History of Catholicism in the United States

- Religious leaders from the San Francisco Bay Area

- African-American Roman Catholicism