Draft:Coinage of Picenum

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 2 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 1,762 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

Coinage of Picenum consists of the monetary issuance of the communities in the area, which under Emperor Augustus was included in the Regio V subdivision of Italy.

Traditionally, numismatists have treated the coins of the Picenum communities as part of Greek coinage.[1]

Historical context

[edit]Monetary issuances in the area are concentrated in the 3rd century BC. In this period, the Piceni and Romans formed a military alliance to counter the advance of the Senone Gauls, who had come as far north as the Tiber; in 299 B.C. the first Roman military action occurred in Picenian territory, against the Gallic settlements north of the Esino River.[2] Further confirmation of the military pact between the Romans and the Piceni came from the latter a few years later, when the Samnites, seeking to involve the Piceni in the impending conflict against Rome, warned their Roman allies of the war that the Samnites, coalesced with the Gauls, Etruscans, and Umbrians, planned to wage.[2][3] The conflict resulted in a series of clashes between the Romans and the allied peoples of the Samnites, of which the decisive one was the Battle of Sentinum (295 B.C.), after which the Roman expansion toward the Adriatic was accentuated; in about 290 B.C., Rome expanded its domains to absorb the territory of the Praetutii, south of the Picenum.[3] During the same period, tensions also escalated between the Romans and the Senones: the latter were defeated thanks in part to the support of the Picenes, who sided against the Celtic populations by agreeing to the Roman army's passage through the Picenum. Following the defeat of the Senonians, Rome also acquired the Gallic territories, which bordered Picenum to the north.[3]

Roman conquests significantly changed the geopolitical context in central Italy: Rome's dominions extended north, west, and south of the Picenum, which was surrounded by the Roman state. The lack of autonomy that resulted from this led the Picentes to break their alliance with Rome and revolt against indirect Roman rule. The revolt, led by the city of Ausculum, was unsuccessful and was quelled by the Romans in two separate campaigns, in 269 and 268 BC. As a result, part of the Picente population was deported to Campania, near Salerno;[4] the rest of the Picentes were partially Romanized, while Ausculum was considered civitas foederata, an ally of Rome; in order to keep Ausculum under control, a colony under Latin law was created at Firmum in 264 B.C.[3][5]

Historical context of Ankón

[edit]The city of Ankón (Ancon or Ancona in Latin) was founded, according to Strabo, around 387 B.C. by Greeks of Doric stock, exiles from Syracuse;[4] the colony, with the name Ankón, was founded, as was often the case, in a place where there was already a Greek storehouse.[6]

The name is derived from the Greek word ἀγκῶν (elbow); historical references to Ankón's location and “elbowed” geographic conformation, from which the city takes its name, are found in the writings of Strabo,[4] Pomponius Mela,[7] Pliny the Elder,[8] and Procopius.[9] This etymology is reflected in the type found on the coin, an elbow.

Two famous temples were located in Ankón: one dedicated to Diomedes[10] and another to Aphrodite:[11]

ahead to the temple of Venus, which the Doric Ancona supports

— Juvenal, Satires, IV

In the 3rd century B.C., Rome's gradual expansion into the Picenum territory induced the city of Ankón to accept an alliance with the Romans;[6] in 178 B.C. the city consented to the use of its harbor by the naval duumvirs C. Furio and L. Cornelius Dolabella, whose task with a fleet of twenty vessels was to counter pirate raids by the Illyrians.[2]

Ankón's trade, already flourishing in the Greek period, assumed even greater importance between the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C., following the Roman conquests in the East, which allowed the opening of trade channels with Alexandria, Taranto, Delos and Rhodes.[6]

While retaining its Greek cultural aspect, the polis of Ankón gradually assumed more and more Roman characteristics, becoming, in 90 B.C., a Roman municipium; later, it was initially a triumviral colony and then, at the time of the Augustan viritan assignments, an Augustan colony.[6]

Historical context of Ausculum

[edit]Ausculum corresponds to today's Ascoli Piceno. The main ethnogenesis of the Italic Osco-Umbrian people of the Picenes reports a pre-Roman, allogenic civilization of the Middle Adriatic but originating in the upper Sabine region, which in ancient times had Ausculum as its capital.[10] This ethnogenesis draws sources from the Roman literary tradition that places at the origin of the Picenian civilization a ver sacrum performed by Sabine peoples.[10]

In 299 B.C., the Picenes formed an alliance with the Romans to counter the incursions of the Senones,[2] and later stood by Rome's side in the conflict against the Samnites, Etruscans, Umbrians, and Gauls.[3] Around 269 B.C., the Picenes broke their alliance with the Romans as a result of the significant geopolitical change that had taken place in the Picenum, which was essentially hegemonized by Rome. The revolt, led by Ausculum, was suppressed in two successive military campaigns carried out by Rome in 269 and 268 BC.[3] For Ausculum, the conflict was resolved in a less radical way than for the rest of the Picenum cities; in fact, unlike them, it was considered civitas foederata, allied to Rome.[3]

Historical context of Firmum

[edit]A Roman colony was deduced at Firmum, which was located on the site of modern Fermo, in 266 BC. The purpose of this dedication, in addition to maintaining strong political control over the region, was also to establish loyal outposts on the Adriatic side of central Italy in case of invasions from the sea. The Roman settlers who arrived in the Fermo area were numerous, in view of the fact that the Picenes deported from there were sent to found and replenish numerous Italic cities; moreover, the process of Romanization was quite rapid.[12] The Romans carried out several urban works to strengthen Firmum's strategic position; situated on Sabulo Hill, the city gradually came to expand on the eastern slope, where settlers' dwellings arose. A forum, baths and a theater were built. The successful Romanization of the territory is confirmed by the loyalty that, over time, was shown in battle by the inhabitants of Firmum.[12]

In 220 B.C., many of Firmum's citizens took part in the Battle of Telamon, in which Rome defeated the Gauls and expanded its possessions in northern Italy.[12] During the Social War, the armies of the insurgent Italic peoples, who had conquered the numerous Roman Adriatic colonies, were unable to occupy Firmum.[12]

Historical context of Hatria

[edit]Hatria covers the site of modern Atri; a Latin colony was created there shortly after 290 BC. Coins, cast, were issued after this date, in the first half of the 3rd century. The coins of Hatria were first thought to be the heaviest and oldest in Italy; later they were re-dated.[13]

Monetary context

[edit]There are two major monetary contexts in the Picenum. On the one hand there is that of the polis of Greek origin Ankón (present-day Ancona), with minted coins; on the other hand there is the context of Italic communities, characterized by cast coins (aes grave), and only later by hammer coinage.[14]

In particular, the cast coins show a pound subdivided into base 10 instead of base 12. This subdivision is characteristic of some communities located on the Adriatic coast. In addition to those in Picenum, some communities in Umbria (Ariminum), the Vestini, and Apulia (Luceria, Venosa) have this subdivision. The decimal subdivision was also used by Capua.[15]

In this case the hamlets take different names than those used in the Tyrrhenian coast. Thus we speak of biuncia, teruncia, quadruncia, and quincuncia, that is, from the value of 2, 3, 4, or 5 ounces. However, the pound of reference differs between communities: about 379 g in Ariminum and Hatria, or about 341 g in Apulia.[15]

Coinage of Ankón

[edit]| Ankon: bronze | |

|---|---|

| |

| Head of Aphrodite; below, letter M (sigma?), here barely legible | Right arm with palm branch; below, ΑΓΚΟΝ, here barely legible |

| Æ, 21mm (9.99 g); circa 300-250 a.C. | |

Of the coinage of Ankón, present-day Ancona, only one type has survived.[16] The date has not yet been precisely defined, but specimens have been found in tombs from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. The coin is hammer struck and bears the Greek inscription ΑΓΚΟΝ, or “Ankón,” the name of the city in ancient Greek.[14]

The Greek coin of Ancona is the first ever issued in the Doric city and bears the images described below.[16]

The obverse depicts the profile of Aphrodite, facing to the right; she is crowned with myrtle, a plant sacred to the goddess; she has her hair gathered in a knot and wears earrings; there is the initial “Σ” (sigma or mu, depending on the reading direction). The border is pearled. Identification with Aphrodite is provided by the passages below from Catullus and Juvenal, which testify to the presence in the city of a temple dedicated to the goddess. The identification of the female figure on the obverse with Aphrodite is already present in Eckhel, considered the founder of numismatics as a science; in this regard he also cites the passage from Catullus:[1]

Now, O divine creature of the cerulean sea, thou who inhabitest the sacred Idalius and the exposed Urius, who dwellest in Ancona and in Cnidus rich in reeds, [thou who dwellest] in Amatunte, in Golgi and in Durazzo, tavern of the Adriatic...

— Cattulus, cary 36, 11-14

The prodigious bulk of an Adriatic rumble happened before the temple of Venus, which the Doric Ancona raises, and filled the nets...

— Juvenal, Satire 4, 40

On the reverse is a nude right arm bent at the elbow, with the hand clutching a twig, perhaps of myrtle, or palm; under the arm is the inscription ΑΓΚΩΝ (Ankōn) and above it are two eight-rayed stars, interpreted as the constellation Gemini, or Castor and Pollux, protectors of sailors. Overall, the coin's reverse is analogous to a coat of arms, as the image of the arm recalls the name of the city and the two stars recall the protective function of the elbow-shaped promontory against the sea waves. The edge of the reverse is also pearled.[14]

Ankón's was the northernmost Greek mint in the Adriatic. The dating of the first issue and the period of circulation proposed by authors vary within the third century B.C. (290 B.C. to 215 B.C.); all agree that Ankón's Greek coinage ceased with the Romanization of the city and the massive introduction of Roman coins. The coins of Ankón are characterized by considerable weight variation, which has been interpreted as evidence of a long period of issuance.[16]

There is still debate about whether the Greek coinage of Ankón belongs to the Roman or the Greek monetary system. There is also a synthesis hypothesis: when the city began minting coinage, it would have chosen weight characteristics that could fit both the Syracusan system and the Roman and Central-Italic systems, which would explain modern uncertainties about attribution to one or the other system. The Ankón coin would thus have been a semiquaint respecting the weight of the old Syracuse lithra.[17]

Equally lively is the debate over the interpretation of the initial “Σ”; those who advocate the earliest dating interpret the initials present in the obverse as the initial of “half obol” or “hemilitron”; according to these scholars the coin would have been part of the Greek monetary system. In contrast, scholars who lean toward the more recent dating interpret the sigma as the initial of “semiuncia,” as is normal in coins that follow the Roman monetary system, as would be the case here.[17] There are other scholars who read mu and not sigma and believe that this initial, which is also common in coins of Syracuse, is not related to the value of the coin. Finally, other scholars speculate that sigma is the initial of the city of Syracuse.[16]

The Ankón coin has distinctly Greek characteristics, not only, of course, in the legend, but also in the style, depth and relief of the coinage, as well as the symbolism. The similarities with coeval Syracusan coins are remarkable. Also significant is the fact that this coin is minted, and the minting technique is an exception in the coinage of Picenum and neighboring areas, where the fused coin (aes grave) dominates.[18]

From the 3rd and up to the 1st century B.C., Greek coinage in Ankón coexists with Roman coinage, as evidenced by the 2008 Ankón finds in Via Barilari and Via Podesti.[19] Among the coins found at these sites, however, specimens from Neapoli, Taras (Taranto), Sikyōn (Sicyon), Thespiaí (Thespiae), Korkyra (Corfu), Kórinthos (Corinth), and Epidamnos also appear, testifying to contacts with Greek centers.[20]

Serving as evidence of the relations between the metropolis Syracuse and its colony Ankón is the Syracusan drachma in the numismatic collection of the National Archaeological Museum of the Marches, of Ankón origin. It was issued about 380 B.C., the time of Ankón's founding; it bears on the obverse the inscription ΣΥΡΑ and the head of Athena with a Corinthian helmet decorated with a crown; on the reverse a starfish (or eight-rayed sun) between two dolphins. In addition to the coin just described, issued in the period of Dionysius I, another Syracusan coin found in Ancona is the hemilithra with the head of Artemis on the obverse and on the reverse a thunderbolt and the inscription Ἀγαθοκλῆς (Agathoklēs), issued in the period of the Syracuse tyrant Agathocles, who revitalized the Syracusan Adriatic policy of Dionysius I. This coin is also in the National Archaeological Museum of the Marches.[14]

The coin is cataloged as Historia Numorum Italy 1.[14]

Coinage of Ausculum

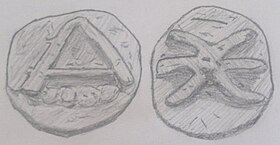

[edit]| Ausculum: quadruncia | |

|---|---|

| |

| A; bottom: value sign. | Lightning |

| Aes grave. | |

A series of cast coins characterized by the letter A was dubiously attributed to this center.[21]

More recent authors attribute this series to another center with this name, Ascoli Satriano, based on the provenance of the specimens found; this coinage is placed temporally at the end of the 3rd century. Other Enean coins minted in the 3rd century also belong to the same center.[14]

The series consists of five pieces: quadruncia, teruncia, biuncia, ounce and semioncia. These coins are normally cataloged as Thurow 174-178. The axis has a theoretical weight of about 98g. The division of the as into 10 ounces is also found in other centers of Apulia, such as Lucera.[14]

It bears on the obverse a large A occupying the entire field and a number of tortelli equal to the value in ounces. The reverse depicts a lightning bolt.[21]

Coinage of Firmum

[edit]The coins attributed to Firmum are two cast bronze coins (aes grave): a teruncia bearing the legend FIR and a biuncia with the same legend but sinistrodextral, that is, written from right to left.[22]

Few specimens are known, and so the determination of the weight value of the pound has uncertainties.[23] The same determination as to whether the monetary system articles in decimal form (axis divided into ten ounces) or duodecimal form (divided into twelve ounces) is doubtful, as is the dating itself.[23]

Vecchi inclines toward the first hypothesis and reports for the teruncia (quadrant) weights between 97 and 58 grams while for the bioncia the weights (sextant) range from 49 to 38 grams.[22]

Rutter et al. instead advocate duodecimal articulation and indicate an axis of about 289 grams. Accordingly, the coins are referred to as quadrant and sextant.[14]

The quadrant or teruncia has a young person's head on the obverse and the value sign consisting of three dots. The reverse depicts an ox head on the obverse and the legend FIR.[22]

The sextant or biuncia has on its obverse a bipenal axe with the value sign consisting of two dots. The reverse depicts a spearhead and the legend FIR from right to left.[22]

The coins are cataloged as Old 245 and 247 or as Historia Numorum Italy 9 and 10.[14]

Coinage of Hatria

[edit]| Hatria: as | |

|---|---|

| |

| HAT, Head of Silenus face; value mark above. | HAT, sleeping dog; value mark above. |

| Æ Aes grave: as. Weight of known specimens: 415-322 g | |

A series of aes grave consisting of an as and six fractions is attributed to Hatria. The as is subdivided into ten ounces and not twelve as in use in Rome and other Italic populations. This type of subdivision is also present, as already seen, at Ausculum Picenum, and in the coinage of Capua, Ariminum, Luceria, Venusia, etc.[14]

| Hatria: quadruncia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Apollo to the left and value sign | HAT cantarus and ivy leaf at the top |

| Æ: quadruncia (aes grave), circa 280 a.C.; 193,74 g | |

The coins are quincunx, quadruncia, teruncia, biuncia, uncia, and semuncia. The series is based on an axis weighing about 372 grams.[14]

These coins are cataloged as Old, 236 to 244, or as Historia Numorum Italy 11 to 17.[14]

The coins bear an indication of value, as does the coinage of other Italic and Etruscan communities. The value is expressed through a number of dots equal to the number of ounces the coin was worth. For the axis one can find either the letter Ι or an archaic L. The semiuncia is indicated by an archaic sigma.[14]

| Coins | |||

| As | Head of Silenus, facing front | HAT Sleeping dog | Thurlow-Vecchi 181, HN Italy 11 |

| Quincunx | Pegasus to the right, five dots | HAT Head of woman in a murex shell | Thurlow-Vecchi 182, HN Italy 12 |

| Quadruncia | Head of man (Apollo?). Four dots | HAT Cantarus (or craters) | Thurlow-Vecchi 183, HN Italy 13 |

| Teruncia | Race. Three dots | HAT Dolphin | Thurlow-Vecchi 184, HN Italy 14 |

| Biuncia | Rooster. Twodots | HAT Shoe | Thurlow-Vecchi 185, HN Italy 15 |

| Uncia | Anchor. One dot | HAT around a dot | Thurlow-Vecchi 186, HN Italy 16 |

| Uncia | Anchor. H | HAT around a dot | Thurlow-Vecchi 186a, HN Italy – |

| Semuncia | A | H | Thurlow-Vecchi 187, HN Italy 17 |

Findings

[edit]The coins featured in IGCH are:

4 aes grave of Hatria, found in the treasure that came to light in 1925 in Città Sant'Angelo, along with 2 denarii, 144 quinarii and 3156 Roman bronze coins. In addition to the Roman coins there are five other bronze coins from the following centers: Vetulonia, Capua, Brundisium and Paestum.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hilarius Eckhel, Joseph (1792–1798). Doctrina numorum veterum (in Latin). Vienna: Degen et al.

- ^ a b c d Titus Livius. Ab Urbe condita libri (in Latin). Vol. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Naso, Alessandro (2000). I Piceni. Storia e archeologia delle Marche in epoca preromana [The Picentes. History and archaeology of the Marches in pre-Roman times.] (in Italian). Milan: Longanesi.

- ^ a b c Strabo. Γεωγραφικά (in Ancient Greek).

- ^ Devoto, Giacomo (1951). Gli antichi Italici [The ancient Italics] (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Florence: Vallecchi.

- ^ a b c d Landolfi, Maurizio. Dalle origini alla città del tardo impero [From the origins to the city of the late empire] (in Italian). Vol. 1.

- ^ Pomponius Mela. Cosmography (in Latin). Vol. 2.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia [History of Nature] (in Latin). Vol. 3.

- ^ Procopius. De bello Gotico (in Latin). Vol. 2.

- ^ a b c Piceni popolo d'Europa [Picenes people of Europe] (in Italian). De Luca Editori d'Arte. 2000. ISBN 978-8880163329.

- ^ Juvenal. Satires.

- ^ a b c d Michetti, Giuseppe (1980). Fermo nella storia [Fermo in history] (in Italian). Fermo: La rapida.

- ^ Luigi Sorricchio (1911). Hatria = Atri (in Italian). Rome: Tipografia Del Senato.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rutter, N. K.; Burnett, A. M.; Crawford, M. H.; Johnston, A. E. M.; Jessop, M., eds. (1990). Historia Numorum: Italy. London: The British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714118017.

- ^ a b Catalli, Fiorenzo (1995). Monete dell'Italia antica [Coins of ancient Italy] (in Italian). Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato.

- ^ a b c d Dubbini, Marco; Mancinelli, Giancarlo (2009). "La monetazione del III secolo a.C." [The coinage of the third century BC.]. Storia delle monete di Ancona [History of the coins of Ancona] (in Italian). Ancona: Il lavoro editoriale. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-88-7663-451-2.

- ^ a b Asolati, Michele (1998). "Per la storia di Ancona greca: elementi di datazione della monetazione" [For the history of Greek Ancona: elements of coinage dating.]. In Braccesi, Lorenzo (ed.). Hesperìa. Studi sulla grecità di Occidente [Hesperia. Studies on the Greekness of the West.] (in Italian). Vol. 9. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 141–153. ISBN 88-8265-008-1.

- ^ Casagrande, Giorgio (1985). La monetazione di Ancona all'epoca della colonizzazione greco-siracusana (IV - III secolo a.C.) [The coinage of Ancona at the time of the Greek-Syracusan colonization (4th - 3rd centuries BC)] (in Italian). Ancona: Circolo Culturale Filatelico Numismatico Dorico.

- ^ Pignocchi, Gaia (2015). "L'abitato preromano ed ellenistico-romano di Ancona" [The pre-Roman and Hellenistic-Roman settlement of Ancona]. In Emanuelli, Flavia; Iacobone, Gianfranco (eds.). Ancona greca e romana e il suo porto [Greek and Roman Ancona and its port] (in Italian). Ancona: Edizioni Italic. ISBN 9788869740039.

- ^ Gorini, Giovanni (1997). "La moneta greca in area alto e medioadriatica" [Greek currency in the upper and middle Adriatic area]. Atti e memorie della Deputazione di Storia Patria delle Marche [Proceedings and Memoirs of the Deputation of the Homeland History of the Marches] (in Italian). Vol. 102.

- ^ a b Vincent Head, Barclay (1911). Historia Numorum: a Manual of Greek Numismatics (2nd ed.). London: Oxford.

- ^ a b c d Vecchi, Italo (2013). Italian Cast Coinage, A descriptive catalogue of the cast coinage of Rome and Italy. London: London Ancient Coins. ISBN 978-0-9575784-0-1.

- ^ a b Catalli, Fiorenzo (1995). Monete dell'Italia antica [Coins of ancient Italy] (in Italian). IPZS. ISBN 88-240-3977-4.

- ^ Thompson, Margaret; Mørkholm, Otto; M. Kraay, Colin, eds. (1973). An Inventory of Greek Coin Hoards (IGCH). New York: ANS. ISBN 978-0-89722-068-2.

Bibliography

[edit]- Asolati, Michele (1998). "Per la storia di Ancona greca: elementi di datazione della monetazione" [For the history of Greek Ancona: elements of coinage dating.]. In Braccesi, Lorenzo (ed.). Hesperìa. Studi sulla grecità di Occidente [Hesperia. Studies on the Greekness of the West.] (in Italian). Vol. 9. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 141–153. ISBN 88-8265-008-1.

- Catalli, Fiorenzo (1995). Monete dell'Italia antica [Coins of ancient Italy] (in Italian). IPZS. ISBN 88-240-3977-4.

- Dubbini, Marco; Mancinelli, Giancarlo (2009). "La monetazione del III secolo a.C." [The coinage of the third century BC.]. Storia delle monete di Ancona [History of the coins of Ancona] (in Italian). Ancona: Il lavoro editoriale. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-88-7663-451-2.

- Haeberlin, Ernst (1910). Aes Grave, Das Schwergeld Roms und Mittelitaliens einschließlich der ihm vorausgehenden Rohbronzewährung [Aes Grave, The heavy money of Rome and central Italy including the preceding raw bronze currency] (in German). Halle.

- Vincent Head, Barclay (1911). Historia Numorum: a Manual of Greek Numismatics (2nd ed.). London: Oxford.

- Allen Sydenham, Edward (1926). Aes Grave: A Study of the Cast Coinages of Rome and Central Italy. London: Spink.

- N. Rutter, Keith; et al. (et al.) (2001). Historia Nummorum - Italy. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-1801-X.

- Thompson, Margaret; Mørkholm, Otto; M. Kraay, Colin, eds. (1973). An Inventory of Greek Coin Hoards (IGCH). New York: ANS. ISBN 978-0-89722-068-2.

- Vecchi, Italo (2013). Italian Cast Coinage, A descriptive catalogue of the cast coinage of Rome and Italy. London: London Ancient Coins. ISBN 978-0-9575784-0-1.