Draft:Bonapartism (Marxist concept)

| An editor has marked this as a promising draft and requests that, should it go unedited for six months, G13 deletion be postponed, either by making a dummy/minor edit to the page, or by improving and submitting it for review. Last edited by CommonsDelinker (talk | contribs) 6 days ago. (Update) |

| Submission declined on 2 April 2023 by Bilorv (talk). This submission is not adequately supported by reliable sources. Reliable sources are required so that information can be verified. If you need help with referencing, please see Referencing for beginners and Citing sources.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

Comment: This topic is undoubtedly notable but the sources given—original texts of Marxism—do not show this. Reliable sources such as academic journals or magazines are needed to combine these sources without synthesis. A simpler approach would be to expand Bonapartism#Marxism, and if this section becomes too large to be contained in that article then a split can occur. — Bilorv (talk) 18:48, 2 April 2023 (UTC)

Comment: This topic is undoubtedly notable but the sources given—original texts of Marxism—do not show this. Reliable sources such as academic journals or magazines are needed to combine these sources without synthesis. A simpler approach would be to expand Bonapartism#Marxism, and if this section becomes too large to be contained in that article then a split can occur. — Bilorv (talk) 18:48, 2 April 2023 (UTC)

This article possibly contains original research. (February 2023) |

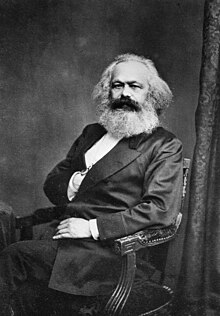

Karl Marx developed the term Bonapartism to explain and describe the character of the regimes that existed under Napoleon I and Napoleon III. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, written by Marx in 1852, outlines that the phenomena of Bonapartism emerges after an often prolonged period of intense class struggle and both classes have become exhausted.[1] It is sometimes referred to as 'bourgeois Bonapartism'.

Marxist theory posits that the state historically arises as a tool for class oppression.[2] In periods of economic stability, the state is used by the ruling class to dominate the oppressed class. During periods of economic crisis, in the case that neither the ruling class nor the working class are capable of taking full control of the state and striking a decisive blow against the other, out of necessity to conquer the impasse an individual will rise to the head of the state.

Using the method of dialectical materialism Marx was able to observe the underlying laws in operation in France and draw out generalisations of what constitutes a Bonapartist regime.[3]

For Marxists, Bonapartism is an elastic term but is often used to illustrate the balance of class forces. The emergence of individuals in history who seemingly rise above class society is explained by the Marxist theory of the role of the individual in history.[4]

Bonapartism is resorted to in order to maintain the rule of the bourgeoisie after other options are no longer available to avoid a collapse of capitalism or socialist revolution.[5]

Features of Bonapartism

[edit]

Bonapartism, as described by Marx, is a phenomenon that emerges from the class struggle which must be understood as a dialectical historical process. The political character of a regime is determined by the relations of one class to another.

Generally, the bourgeoisie is reluctant to resort to Bonapartism. Engels said that in the final analysis, the state is formed of 'special bodies of armed men'.[6] Under a Bonapartist regime, this is revealed without bourgeois democratic norms to conceal it. It often 'rules by the sword' as a military dictatorship to keep the classes in check. This exposes the state as a tool of class oppression, which as well as being a costly affair for the bourgeoisie, can spur the revolutionary mass of workers into action, once again threatening their class dominance.

In order to keep so-called peace between the ruling and oppressed class, a Bonapartist leader is compelled to balance the interests of each class. This takes the form of both repression and concession. At the head of the state, a Bonapartist leader may lean on one class to strike a blow against the other and vice versa.

However, as a result of the instability caused by the impasse in the class struggle, Bonapartism regimes, far from being stable, are often very unstable themselves. Bonapartist leaders often rely on the 'ascendancy of the army'[7] and appear as an arbiter with a sword.

In different forms, regimes of a similar character have appeared throughout the history of class society.[8]

Caesarism

[edit]Caesarism is similar to Bonapartism insofar as they involve balancing the interests of classes. Julius Caesar was balancing the interests of freemen against each other (excluding slaves). However, there are important differences as Marx explained in the 1869 preface to The Eighteenth Brumaire,

"[...] in ancient Rome the class struggle took place only within a privileged minority, between the free rich and the free poor, while the great productive mass of the population, the slaves, formed the purely passive pedestal for these combatants. People forget Sismondi’s significant saying: The Roman proletariat lived at the expense of society, while modern society lives at the expense of the proletariat."[9]

The Tudors

[edit]Bonapartist tendencies can be observed in The Tudors who ruled as absolute monarchists in the late Middle Ages. They came to power after decades of wars between the feudal nobles of England, Scotland, and Wales who were exhausted financially, politically, and as an historically progressive force.[10] The Tudors used the nascent bourgeoisie in London against their enemies, which allowed them to rise above the struggle between the bickering feudal nobles.

In the words of Engels,

"England had finally given up its quixotic wars of conquest in France: in the long run, it would have bled itself white in these wars. The English feudal nobility sought substitute recreation in the Wars of the Roses. It got more than it bargained for: tearing itself to pieces in these wars, it brought the House of Tudor to the throne, and the royal power of the House of Tudor surpassed everything that had gone before or was to come after."[11]

Understanding that the feudal methods of raising armies were no longer adequate to rule, the development of a standing army began in earnest under the Tudors.

Fascism

[edit]Superficially, fascism and Bonapartism share certain features such as, totalitarianism, authoritarianism, and militarism, they are the result of a prolonged period of intense class struggle, and are both acceptable to the bourgeoisie as a last resort in order to prevent a socialist revolution. However, they are different because of the way they relate to classes.

For example, the class basis for fascism is the petty-bourgeoisie, peasantry, and lumpen-proletariat.[12] Fascism does not balance the interests of the classes but rather carries out a counter-revolution against the working class and its organisations such as trade unions and socialist or communist parties. It does this with the support of the aforementioned classes. As Trotsky outlines in Fascism: What it is and how to fight it,

"[...] big capital ruins the middle classes and then, with the help of hired fascist demagogues, incites the despairing petty bourgeoisie against the worker. The bourgeois regime can be preserved only by such murderous means as these. For how long? Until it is overthrown by proletarian revolution."[12]

The similar methods used by fascism and Bonapartism are not enough to make them as one tendency, especially considering the methods at their disposal are sometimes used by the so-called 'democratic bourgeoisie' in the class struggle.

Proletarian Bonapartism

[edit]

After the Russian Civil War, the nature of the state in the Soviet Union was of a peculiar character and unprecedented in history. It therefore led to many theories and attempts to characterise it.

The term 'proletarian Bonapartism' was originally used by Trotsky who also used the term 'soviet Bonapartism'. It was later developed and used by Ted Grant.[13]

Stalinism

[edit]The immense difficulties faced by the revolution led to its weakening and, more so after the death of Lenin in 1924, the rise of a bureaucratic strata in the workers' state. Trotsky characterised the Soviet Union under Stalin as a workers' state but with a parasitic bureaucracy, consisting of the right wing of the Bolsheviks and ex-Tsarist officials, that had come to control it as representatives of the working class.[14]

During Stalin's reign, it was broadly understood that the Soviet Union was a workers' state. However, Trotskyists argued in the absence of full workers' democracy and control, the state was an unhealthy or deformed workers' state.

Initially, Trotsky initially characterised Stalinism as bureaucratic centrism but as the character of Stalinism continued to reveal itself later he described it as proletarian Bonapartist. This was not a change in formulation but merely the term to best describe Stalinism in Marxist terms.[15]

Stalin had not consciously felt out the bureaucracy but rather, as Trotsky put it, the right wing bureaucracy had felt out Stalin.[16] Therefore, after coming to power Stalin was compelled to balance the interests of the working class and peasantry with those of the right wing bureaucracy. In the words of Ted Grant from 1949,

"Stalinism is a form of Bonapartism that bases itself on the proletariat and the institution of state ownership, but it is as different from the norm of a workers’ state as fascism or bourgeois Bonapartism differs from the norm of bourgeois democracy, which is the freest expression of the economic domination and rule of the bourgeoisie."[17]

In contrast to bourgeois Bonapartism, which emerges in bourgeois states, proletarian Bonapartism emerges in workers' states, usually deformed workers' states where the capitalists have been expropriated and capitalism has been abolished. However, the working class are unable to take power and give the workers' state the freest expression of the economic domination and rule of the proletariat.

The term is primarily used to describe the nature of Stalinist regimes in the Soviet Union, as well as regimes in some ex-colonial countries that experienced revolutions.

Colonial Revolution

[edit]In Grant's The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed Workers' States (1978),[18] he draws out the events prior to the colonial revolutions in several colonial and ex-colonial countries. Similar to the backward economic situation in 1917 Russia, the colonial and ex-colonial countries posed many challenges for establishing healthy workers' states.

Notably, in addition to a weak working class, after expropriating the imperialists, the stunted national bourgeoisie were also too weak to assert themselves. Therefore, in the workers' states set up in the image of the Stalinised Soviet Union, a regime emerges with an individual at its head capable of balancing and playing the class interests of the working class, peasantry, and bourgeoisie, against one another.

Mao in China, balanced between classes during and after the Chinese Revolution. Grant characterises Mao's rise as thus,

"Therefore, having balanced between the bourgeoisie and the workers and peasants in order to prevent the workers from taking power, Mao and his gang - after perfecting the state - could then crush the bourgeoisie before turning on the workers and peasants to crush whatever elements of workers' democracy had developed. The bureaucracy then developed a totalitarian one-party dictatorship, centred round the Bonapartist dictatorship of one single individual - Mao."[18]

Other regimes that are characterised as proletarian Bonapartist include the Cuban Revolution, Tito's Yugoslavia, and Ho Chi Minh's Vietnam.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marx 1852". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Origins of the Family". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. VI". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "G.V. Plekhanov: On the Role of the Individual in History (1898)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. VII". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "The State and Revolution — Chapter 1". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. VII". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ Demagogues and dictators: What is Bonapartism?, 22 October 2022, retrieved 2023-02-08

- ^ "18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte - Preface 1869". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I - Chapter Twenty-Seven". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "The Decline of Feudalism and the Rise of the Bourgeoisie". marxists.architexturez.net. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ a b "LEON TROTSKY: Fascism: What it is and how to fight it". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Ted Grant - The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed Workers' States". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-07.

- ^ "Leon Trotsky: The Revolution Betrayed (1936)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ "Leon Trotsky: Two Articles On Centrism (1934)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon. The Revolution betrayed : what is the Soviet Union and where is it going?. OCLC 1291214273.

- ^ "Ted Grant – Reply to David James". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-07.

- ^ a b c "Ted Grant - The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed Workers' States". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.