Draft:Assassination of Carter Harrison Sr.

| Assassination of Carter Harrison Sr. | |

|---|---|

Illustration of Harrison being shot by Prendergast | |

| Location | Residence of Carter Harrison Sr., Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Date | October 28, 1893 131 years ago |

| Target | Carter Harrison Sr. (mayor of Chicago) |

Attack type | Assassination |

| Weapons | .38 revolver manufactured by Smith & Wesson |

| Deaths | 1 (Harrison) |

| Motive | Mental illness; retribution for perceived failure to reward campaign support |

| Convicted | Patrick Eugene Prendergast |

| Verdict | Guilty |

| Convictions | Murder in the first-degree |

| Sentence | Death |

On October 28, 1893, Patrick Eugene Prendergast fatally shot Carter Harrison Sr. (the mayor of Chicago) inside Harrison's residence. Prendergast's assassination of Harrison was driven by a delusion Prendergast held that he was entitled to be appointed the city's corporation counsel (a role he held no qualification for), and that Harrison had wrongfully deprived him of this.

The assassination occurred two days prior to the closing day of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and led to the cancellation of the world's fair's closing ceremony. It quickly drew comparisons to the 1881 assassination of U.S. president James A. Garfield by Charles J. Guiteau. Like Prendergast, Guiteau had been a deranged office seeker whose actions were motivated by their having not been given a patronage appointment that he perceived he was entitled to. For a long time, Harrison's assassination was a well-remembered event in American history. However, it has since fallen into relative obscurity.

In the subsequent trial, Prendergast was found guilty of murder in the first-degree, and was sentenced to death. Legal efforts led by attorney Clarence Darrow to forestall his execution (including an attempt to have Prendergast legally found to be currently insane, a condition which under Illinois law would have rendered him intelligible for execution) were ultimately unsuccessful. Prendergast was executed by hanging.

Background

[edit]Carter Harrison Sr. (victim)

[edit]

Carter Harrison Sr. was an American politician who served two tenures as mayor of Chicago: the first between 1879 and 1887 and the second beginning in 1893.[1] Harrison was a Democrat.[2]

Harrison unsuccessfully ran in 1891 to become mayor again. Harrison was returned to office in early 1893, winning election to an unprecedented fifth term as mayor. His fifth term overlapped with the city's hosting of the World's Columbian Exposition, a significant world's fair.[1]

Harrison was a well-liked mayor.[3][1] Dubbed "the common man's mayor".[4] and "the people's mayor",[5] he made himself accessible to citizens.[4] He took great pleasure in riding around the city's neighborhoods on horseback, stopping to speak with residents.[4] He also made it known that his door was "always open",[4] allowing citizens to drop-in for audiences with him at his residence.[6] He had ordered his staff never to turn away any visitor to his residence.[7] His policy of giving drop-in audiences to residents would lead to him finding himself fatally at the receiving end of gunshots fired by the aggrieved Patrick Eugene Prendergast.[4]

Patrick Eugene Prendergast (perpetrator)

[edit]

The assassination was carried out by newspaper distributor Patrick Eugene Prendergast.

Patrick Eugene Prendergast was born on 6 April 1868 in Cloonamore townland, Inishbofin, an island off the west coast of Ireland.[8] He was baptised in St Colman's Church on 12 April 1868 [9] His parents were Ellen King (1837–1914) and Patrick Prendergast (1840–1886), both of whom were described as teachers at their marriage in Inishbofin on 2 July 1865.[10] His grandfather, William Prendergast, who lost an arm in Pamplona, was an army pensioner who was reported to have died insane. His mother had "repeated attacks of hysterics" and his father died of consumption.[11]

Prendergast was reported to have suffered a severe head injury from a fall at the age of four, from which he was unconscious for a long period of time and suffered vomiting for four weeks after.[11] He was described as a peculiar child, solitary, irritable and excitable, with a poor memory who did poorly in school.[11][12] Patrick arrived in New York on 20 May 1873, aged 5, traveling with his brother William, aged 8, on the SS France. He left home at 16 because of imaginary persecution and by 18 had developed grandiose ideas of his capabilities and became a fanatic for the single-tax promoted by Henry George.[11]

Prendergast became a newspaper distributor in Chicago, where he lobbied for improvements in Chicago's railroad grade crossings, which he saw as a danger to the public. He supported Carter Harrison's 1890s election campaigns under the delusion that if Harrison won the election, Prendergast himself would receive an appointment as the city's corporation counsel.[13] Prendergast had a fixation with writing postcards. In order to support Carter Harrison's pursuit to regain the mayoralty, Prendergast sent rambling postcards to prominent Chicagoans urging them to vote for Harrison. Among those who received such a postcard was prominent lawyer A. S. Trude, who would later prosecute the case against Prendergast in the murder trial that followed the assassination.[14] Prendergast sent these postcards in support of Harrison for more than two years before Harrison was successful in winning the 1893 Chicago mayoral election. Prendergast believed that his letters had been responsible for Harrison's success in the election.[6]

Prendergast visited Chicago City Hall under the delusion that he had been appointed corporation counsel by Harrison. After Prendergast was insistent to a clerk that he held the position, he was brought to meet Adolph Kraus, the incumbent corporation counsel, who showed Prendergast his office and teased him by facetiously asking if he wanted the job.[14] While Prendergast did not have the education or qualifications that required for the office, he was nevertheless angered that he had not been appointed by Harrison to it.[15] After Harrison had spent six months in office without appointing him corporation council or granting him any recognition, Prendergast began to desire revenge against Harrison for the perceived slight.[6]

Prendergast wrote threatening letters to both Harrison and Kraus, a fact which was quickly discovered by investigators following the assassination. One letter to Kraus read, "I want your job. Do not be a fool. Resign. Third and final notice."[4]

Assassination

[edit]

On October 28, 1893 (the day of the assassination), Prendergast purchased a six-chamber .38 revolver manufactured by Smith & Wesson. He would use this weapon to carry out the assassination. Because this model often misfired, he opted to keep the chamber under the hammer empty.[4][6][14]

Per press reports, on the day of the assassination (prior to traveling to Harrison's residence and assassinating Harrison), Prendergast had visited Kraus at his office at City Hall and issued a threat if Kraus did not resign from his office. The news reports stated that Kraus tricked Prendergast into thinking he was about to resign, before escaping by ditching Prendergast in the building’s crowded lobby.[4]

On the day of the assassination, Harrison delivered a speech at the grounds of the World's Columbian Exposition during its "American Cities Day" celebration.[16] American Cities Day saw Harrison host 5,000 mayors and city councilmen of U.S. cities at the fairgrounds.[6] It is believed to have been the largest-ever gathering of United States mayors.[16] In his speech, Harrison remarked on Chicago's ascendence in the ranks of world cities, promising that by the end of the next half-century, "London will be trembling lest Chicago shall surpass her," and expressed wish of living to see that day.[1] After his speech, Harrison toured exhibits at the exposition and mingled with the crowds.[7]

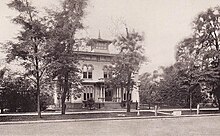

In the evening, Harrison returned to his residence.[6] Soon afterwards his son William Preston Harrison returned to the house as well, and joined his father for dinner and in order to discuss a potential article to be published in the Chicago Times newspaper that the family operated. They were joined at dinner by Mayor Harrison's youngest daughter, Sophie. Towards the end of the dinner, the mayor fell asleep in his chair.[7]

Prendergast rang the doorbell of Harrison's home. Harrison's maid, Mary Hanson, answered the door, and requested that Prendergast return in a half-hour. When Prendergast returned, she asked him to wait in the hall. Hanson went to retrieve the mayor.[6] Hanson had thought Prendergast looked familiar and mistook him for a city official. When Harrison asked who was here to see him, she told him it was a city official.[7] Hanson then herself went to join other household staff for dinner in the kitchen,[6] while Harrison his chair to greet his visitor. Harrison went through a doorway that connected the dining room directly to the front hall of the residence.[7]

Soon after Harrison walked into the doorway, four gunshots were fired by Prendergast into him. The first gunshot entered Harrison's left hand, exiting through his palm. The next went through his abdomen roughly five inches above his navel, and stopped in his intestine. The third made a roughly three-inch wound under his right nipple. The final shot appears to have been fired while Harrison was on the ground suffering the pain from the first three shots. It traveled four inches below the skin below the rear of his right shoulder.[7][17]

After shooting the mayor, Prendergast ran out of the residence through its front door. Harrison's coachman, Paul Elliason Risberg, having heard the gunshots from the level of the House below, had quickly run up the stairs to the entrance level with a handgun. Noticing Risberg emerging into the front hall, the fleeing Prendergast shot into the front hall. Risberg returned fire. Neither were wounded in this exchange.[7][17]

The noise of the commotion attracted the Harrisons' neighbor William Chalmers (the president of the Allis-Chalmers steel company) to quickly run into the residence.[7][1] Household servants also ran to Mayor Harrison's side.[6] Harrison had pulled himself through the dining room and into a butler's pantry that led to the kitchen before collapsing.[7] William Preston Harrison, who was upstairs, signaled for help by activating an emergency signal in the upstairs, then ran outside to ask a passing bicyclist to get retrieve family doctor.[7] When he came to his father's side William Preston Harrison asked, "father's not hurt, is he?" to which the mayor responded, "Yes. I am shot. I will die."[6] Mayor Harrison was bleeding from his mouth and remained conscious for roughly twelve minutes.[7] Chamlers and William Preston Harrison carried the wounded mayor to a sofa.[1] Chalmers placed his folded coat underneath Harrison's head. He argued that Harrison was wrong in his belief that he had been shot in his heart. Harrison responded, I tell you I am, this is death." Chalmers would later remark, "he died angry because I didn't believe him. Even in death, he is emphatic and imperious."[6] As doctors and police arrived, Harrison remarked, "doctors are no good now," as he was nearing death. His last words were reported to be, "Give me water. Where is Annie," referring to his fiancé Annie Howard, who had been visiting the nearby home of Harrison's son Carter Harrison Jr. at the time of the assassination. Hall arrived around the time that the mayor succumbed to internal hemorrhaging.[7] His death came approximately twenty or twenty-three minutes after he was shot.[3][4]

Prendergast's surrender to police

[edit]After fleeing the Harrison residence, the assassin ran further to escape pursuers.[18] He ran for several blocks before catching a ride on a streetcar.[1] He then entered the Des Plaines Street police station, where he surrendered himself approximately thirty or forty-five minutes after shooting Harrison.[1][18][14][4] In surrendering himself, he told the desk sergeant,[7] "lock me up. I am the man who shot the mayor."[6] He still had the gun in his possession when he surrendered.[18] Those at the police station were aware of the mayor's assassination, having been alerted by telephone.[4] The smell of burned powder and the revolver's empty chambers affirmed to the police department that Prendergast was telling the truth.[18] Prendergast gave his name as being Eugene Patrick Prendergast (inverting his first and middle name).[19][20] Prendergast was taken from the Des Plaines Street police station to the Central police station, located downtown, where the building was quickly surrounded by a crowd of 5,000 people. Fearing potential mob violence, at 11:15 PM, Prendergast was stealthily hurried into a wagon and taken to another station located on the North Side of the city, where he was lodged in the county jail pending trial.[17]

A news report described Prendergast as, "dressed in a shabby-genteel manner," with, "[insanity] written both in his features and in the restlessness of his manner." While this report noted that it appeared he was an, "insane or partially demented man," it also reported that he had committed the murder, "in cold-blood and deliberate[ly]," having, "arrived at the Harrison mansion bent on murder."[21]

When interviewed by police, Prendergast gave varying stories as to his motive, including the failed appointment and the mayor's failure to elevate train track crossings.[19] In a formal statement, he declared that Harrison, "deserved to be shot. He did not keep his promise to me."[1] A mere twenty minutes after his arrest, Michael Brennan, the general superintendent (head) of the Chicago Police Department, spoke with him. When speaking to news reporters, Brennan characterized Prendergast was insane, idiomatically calling him, "as crazy as a bed bug "[4] and “mad as a March hare.[22] Other police shared with the press their belief that Prendergast was mentally unwell. Joseph Kipley, the assistant chief of police, remarked that, “Prendergast had talked and acted like a crazy man."[4]

Autopsy, coroner's inquest, grand jury decision, and arraignment

[edit]The autopsy of Harrison was conducted by Dr. Ludvig Hektoen and Dr. Louis G. Mitchell.[23] The morning following the assassination, James McHale (the Cook County coroner) conducted the coroner's inquest at the Harrison residence.[24] During the inquest, Prednergast (accompanied by guards) stood in the foyer where the assassination had occurred while witnesses gave testimony in the south back parlor of the residence.[7] The witnesses included Harrison's son William Preston, maid Mary Hansen, and coachman Barth Reisberg. The only other two witnesses interviewed were police sergeants.[24] Before coroner’s jury, witnesses identified Prendergast as the killer and described the events of the previous night.[4][24]

Prendergast communicated sympathy for Harrison's bereaved family, but refused to speak to the inquest jurors.[7]

The jurors agreed with the testimony of the witnesses as to the manner of Harrison's death, and decided to remand the matter to a grand jury that had been impaneled.[7][24] Prendergast was then returned to the Cook County Jail, and placed in cell 11 (the same cell where Louis Lingg had famously committed suicide only years earlier).[24]

Reaction

[edit]Harrison's assassination was met with a significant national reaction,[25][7] and was one of the most sensationalized events in then-recent memory.[12] The Chicago Daily News quickly published a rare evening special edition on the night of the assassination.[25]

Parallels were quickly drawn between the assassination of Harrison by Prendergast and the 1881 assassination of U.S. president James A. Garfield by Charles J. Guiteau.[7][26] Similarly to Prendergast, Guiteau was a deranged office seeker whose motive was a failure to be given a patronage appointment that he perceived he was entitled to as a reward for his campaign support to Garfield.[7] Prendergast greatly dislike for the parallels being drawn between himself and Guiteau; he regarded Guiteau lowly and saw himself as superior to Guiteau.[27]

Harrison's assassination was regarded to possbily be the most sensationalized news item since Garfield's assassination,[12] and generated what a telegraph official remarked was the largest reaction to anything since Garfield's assassination.[7] Several newspapers expressed hope that Harrison and Garfield's assassinations would motivate reforms to civil service that would eliminate the patronage system.[7] The public was particularly alarmed by Harrison's assassination, because it was perceived to be part of a pattern of violent crimes committed against officials, other examples of which included Garfield's assassination years earlier and the more recent assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II earlier in 1893.[12]

Even before the mayor succumbed to his death, news spread of the shooting and crowds began to form outside of his residence. Massive crowds would continue to populate the outside of the house for the next three days.[7][12] Harrison was deeply mourned by Chicagoans. Flags across the city were lowered to half-mast,[7][4] and buildings (both municipal and private) were covered in black cloth. The City Council met to arrange the funeral, leaving the mayor's chair in the chamber empty during the meeting.[7]

In the days following the assassination, newspapers speculated that Prendergast may have suffered from insanity. Speculation on Prendergast's mental condition became an item of heavy public interest.[4] Despite the initial public perception of Prendergast as a mentally troubled individual, as more became known about his background the public began to view him more as an angered egomaniac that had killed as an act of revenge.[12]

The assassination of Harrison, who had sixteen years earlier served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, elicited wide discussion in the nation's capitol of Washington, D.C.. Many publicly expressed great sorrow over his passing, including many of his former federal government colleagues.[28]

An outpouring of messages were delivered by officials, including from President Grover Cleveland, former president Benjamin Harrison, and Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld.[7] The day after the assassination, the Harrison family received several friends at their residence who came to deliver condolence cards. Among these visitors was U.S. Second Lady Letitia Stevenson.[7] Harrison’s fiancé (whose wedding to Harrison was to have been only a matter of weeks after the day of the assassination) had great difficulty coping with his death (which she witnessed the final moments of), suffering hysteria in its aftermath which she received sedation for.[4]

On October 29, it was announced that the closing ceremony of the World's Columbian Exposition, scheduled for the next day, would be canceled.[16] It was replaced with a memorial ceremony for Harrison,[14] which was held in the exposition's Festival Hall.[6] Instead of the planned highly-attended grand closing to the fair, the fair's final days were quiet and poorly attended by "weary and uninterested" crowds. The Chicago Daily News reported that the mood during the closing day of the fair was "dull and cheerless" as a result of Harrison's assassination, observing, "there was an air of desolation over all. From every flagstaff drooped a banner at half-mast."[19]

Display of Harrison's remains at residence, "Pageant of Grief", and laying in state at Chicago City Hall

[edit]Harrison's body initially laid on display for mourners in his residence's downstair's window. The City Council organized a "Pageant of Grief". In the morning of October 31, Harrison's body was transported from his residence to Chicago City Hall, where it would lay in state and be viewed by the public. Harrison was placed in a heavy red cedar "state coffin", which featured a glass viewing window. Pallbearers included former Illinois governor Richard James Oglesby, Judge Lyman Trumbull, Major General Nelson Miles, along with eight fire captains and seven police captains. Before a crowd of approximately 300 gathered outside the house, the remains were carried from the home and placed in a hearse. A parade of carriages, military guards, and police guards accompanied the hearse as it traveled to Chicago City Hall. Many city officials took part in this procession.[7]

A space was created for Harrison to be displayed at Chicago City Hall by partitioning off a section of a ground floor hallway. Harrison's coffin was placed in a black catafalque surrounded by flowers and black draping.[7] While Harrison laid in state at Chicago City Hall, vast numbers lined up outside for hours to see his open casket.[6] Over one hundred thousand waited to view Harrison's remains.[7]

Funeral

[edit]The following day, Harrison's remains were given what Donald L. Miller later described as, "the most impressive funeral in the young city's history."[6] Harrison's funeral was described as being, "of such proportions [never] before seen" for any previous funeral in Chicago's history.[29]

In a grand procession, Harrison's remains were carried first to the Church of the Epiphany where a funeral service was held, and then to Graceland Cemetery where it was interred. The procession was led by a 150 member band. Several other bands were placed further back in the procession.[7] Behind the hearse carriage that carried the catafalque with Harrison's remains was his personal Thoroughbred horse, with her stirrups crossed over her empty saddle. One of Harrison's sons would later remark that nobody would ever again ride the horse after Harrison's death.[6]

The procession that followed behind the hearse included 600 carriages carrying family members, pallbearers, distinguished current and former government officials, and members of various civic organizations.[7] Among those in these carriages were prominent Chicagoans such as Philip Danforth Armour, Marshall Field, Daniel Burnham, and George Pullman.[6] Further mourners marched behind the carriages,[29] Among them were 1,500 uniformed men marched in the procession representing many social groups, military units, municipal government agencies, trade unions, social fraternities, and other organizations.[7] Among those following the hearse (either in carriage or on foot) were Governor Altgeld, city council members, city officials, former city officials, members of the Chicago Board of Education, members of the literary boards, Cook County officials, judges, representatives of the Chicago Bar Association, trustees of the Chicago Sanitary District, park commissioners,, Illinois state officials, members of the World's Columbian Exposition board of commissioners, federal government officials, representatives of typographical unions, representatives from various civic societies, representatives from the Chicago Press Club and Chicago Newspaper Club; members of the Democratic and Republican party central committees; 2,000 city employees; representatives of various political clubs (affiliates of both the Democratic and Republican parties); representatives of German societies; representatives of singing societies; 2,000 representatives of Bohemian societies; 800 members of Catholic uniformed societies and other catholic organizations; Clan na Gael guard; members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians; representatives of Irish literary clubs; representatives of French Canadian society organizations; representatives of Norwegian society organizations; members of Italian society organizations; and general citizens.[29]

Among the honorary pallbearers in the funeral were:

- Francis Adams, judge[29]

- _______ Armour, comptroller of _____[29]

- C. K. G. Billings[29]

- Charles Fitzsimmons, general[29]

- Harlow N. Higinbotham, world's fair board president[29]

- Adolph Kraus, Chicago corporation counsel[29]

- Joseph Medill, former mayor of Chicago[29] and newspaper magnate

- Richard James Oglesby, former governor of Illinois[29]

- Thomas W. Palmer[29]

- Fred W. Peck[29]

- John A. Roche, former mayor of Chicago[29]

- Lyman Turnbull, judge[29]

- R. A. Waller[29]

- Elihu Washburn, former mayor of Chicago[29]

- Frank Wenter,[29] president of the Chicago Sanitary District

- W. F. Winston[29]

It took two hours for the entire procession to pass by any one location.[7] The great duration of the procession came even as an effort was made to keep its formation as compact as possible (with military marching eight abreast, carriages being driven tightly three abreast, and society members being arranged to walk tightly together.[29] The route that the procession took was intentionally meandering to accommodate viewing by vast crowds.[7] The procession was met by thousands of spectating mourners dressed in black.[6] Estimates were that more than 500,000 spectators met the procession.[7] Many mourners wore buttons reading "Our Carter". The procession elicited strong emotional reactions from many Chicagoans in attendance.[6]

1,500 policemen were distributed throughout the parade route to handle crowd control. Despite these efforts, the immense size of the crowds led to some crowd crushes causing a number of women to faint, and a number of people to incur serious injury (with one being taken to the Cook County Hospital.[29]

Procession to church

[edit]In the morning, viewing ended and Harrison's casket was taken outside of the City Hall and placed into an elaborate hearse. The initial procession to the Church of the Epiphany then began, taking several hours along an intentionally-circuitous route before reaching the church.[7]

Church service

[edit]After arriving at the Church of the Epiphany, the casket was brought into the church for a brief Episcopal service.[7]

During the service, Annie Howard (who had been engaged to marry Harrison) broke into what was described as a "hysterical" crying fit being described as having "completely broke down". She was ushered out of the service and taken back to the Harrison residence where she was tended to by a physician. Reports described her as remaining "in a state of complete collapse" for the remainder of the day, but having recovered to a "better" state the following day.[7] Additionally, Preston Harrison –son of the late mayor– fainted during the service and required medical attention.[7]

Procession to cemetery and interment

[edit]

After the service, the funeral procession resumed, traveling from the church to Graceland Cemetery. It took several hours for it to reach Graceland Cemetery.[7]

The second leg of the procession was led by a platoon of police officers. The platoon was respectively followed in the procession by: the Iowa state band, police officer Austin J. Doyle (the "marshal of the day") and mounted aides; General Nelson A. Miles and his personal staff; department staff of army officers who were connected with the World's Fair; Colonel R. E. A. Crofton of Fort Sheridan and his staff; the 15th Infantry Regiment of the United States Army (stationed at Fort Sheridan); a U.S. Army light artillery battery; the First Brigade of the Illinois National Guard; Chicago Police Chief Michael Brennan and four companies of police; a battalion featuring four companies of the Chicago Fire Department; the Chicago Hussars; an aldermanic "guard of honor" featuring seven city council members; the honorary pallbearers; the funeral car and the active pallbearers (eight captains of the police and fire departments); followed by mourners in carriages.[29]

A short service was held at the cemetery before the coffin was interred in a cemetery vault. Nine days later, the body was quietly moved into the Harrison family plot for its final burial.[7]

Prendergast's legal proceedings

[edit]Arraignment

[edit]On November 2, the grand jury approved an indictment of Prendergast for first-degree murder. Thereafter, on the same day, Prendergast was arraigned before Jude Oliver Horton. Prendergast plead "not guilty". He was described as heavily sweating, trembling, "cowering in terror", and having spoken in a near-whisper when giving his plea.[7][24]

Murder trial

[edit]

________ description of trial

On December 29, 1893, after quick deliberation the jury delivered a guilty verdict and sentenced Prendergast to death by hanging. His execution was scheduled for March 23.[4]

Prosecution's case

[edit]Defense's case

[edit]Verdict

[edit]__________

Prendergast’s attorneys motioned for a new trial, citing errors "in admitting incompetent and improper evidence," as well as claiming that testimony that was allowed during the arraignment about Prendergast's conduct had amounted to compelling Prendergast to "give evidence against himself," in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Judge Brentano considered the motion. On February 24, Brentano denied the motion, sentencing Prendergast to execution on March 23, 1894.[7]

Initial appeal attempts

[edit]By some time in May, Wade had departed from Prengergast's defense and Clarence Darrow had become Prendergast's primary counsel.[7] While it is not clear the exact date when Darrow involved himself in the matter of Prendergast's defense, an article in The New York Times supports that Darrow had involved himself as early as February 1894 in the defense, reporting that Darrow had by February 20 become junior counsel for the defense, and on that date had spoken before the court as part of the defense's arguments to support their motion for a new trial.[12]

Darrow had months earlier left his position as the city's assistant corporation counsel.[22] This was his first murder case,[3] and marked the start of a storied criminal law career for him.[22] Joining Darrow in his representation of Prendergast was James S. Harlan and Stephen S. Gregory.[7][30] Trude continued as the case's prosecutor.[7] Darrow was among Chicago's most boisterous opponents of capital punishment (the death sentence). Darrow had never before represented a defendant in a murder case.[4]

On March 22, the eve of the execution date, the Illinois Supreme Court delivered their refusal to intervene.[7]

Insanity proceeding

[edit]Also on March 22, Prendergast's brother filed a petition on Prendergast's behalf citing Illinois' section 285 of the (then-current) Illinois Criminal Code, which barred the trial or execution of individuals who become "lunatic or insane" after the commission of a crime for as long as the remain in such a mental state. If he were to be deemed insane, this would forbid Prendergast's death sentence from being carried out until such a point that he would be deemed sane.[4][31] The statute required a sanity hearing to take place if it appeared that the condemned may have become insane since the verdict sentencing them to death had been delivered.[12]

Late that night, from the Cook County Criminal Court, Judge Arthur H. Chetlain ordered a two-week reprieve; issuing a de lunatico inquirendo –a writ which ordered for an inquiry to be held in which a jury would rule as to whether or not Prendergast was currently insane. If he were currently insane, it would make him ineligible to be executed. This move by Chetlain was highly unexpected, and he faced tremendous backlash for issuing the reprieve.[7] He was accused of philandering and having exceeded his judicial authority.[7][32] In response to criticism, Chetlain recused himself from the matter and the case was given to Judge John Barton Payne.[7]

Following many delays, the insanity proceedings began on June 20, 1894. Despite objections by the defense, Trude was allowed to continue representing the state against Prendergast.[12]

The proceedings received renewed pubic interest after French president Sadi Carnot was assassinated on June 24. Many had already been concerned after Harrison's assasination that it was part of a perceived trend of violent crimes being committed against officials, with other examples including President Garfield's assassination years earlier and the assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II months before Harrison's assassination.[12]

Richard Allen Morton has written,

Unlike the first trial, where Trude had overwhelmed the defense, Darrow was not intimidated and fought and objected at every point, often to the judge's irritation. He was so vigorous in this regard that he might be trying to lay the groundwork for a possible appeal. Also adding to the rising emotion of the trial were frequent, apparently irrational, punctuations by Prendergast himself, which the newspapers dismissed once again as merely role-playing.[7]

State's case

[edit]Defense's case

[edit]Verdict

[edit]On July 3, the jury delivered a verdict that found Prendergast that Prendergast was sane. Prendergast was then scheduled for execution ten days later (on July 13).[12][4] Darrow made a motion for a new proceeding, which Judge Payne denied.[12][7] Prendergast's appeal was a rare loss in Darrow's legal career.[4]

Further efforts to prevent Prendergast's execution

[edit]On July 11, Darrow and Harlan held a morning meeting with Governor John Peter Altgeld in Springfield, Illinois (the state's capital city), but were unsuccessful at persuading Altgeld to issue a pardon. The governor was already suffering damage to his public perception for his pardons of some of those convicted for the Haymarket Riot.[7] Altgeld had been Darrow's law partner, and the year before Darrow had persuaded him to pardon anarchists that had been convicted in relation to the Haymarket affair. Those pardons had caused severe damage to Altgeld's political popularity. Already sinking with Chicago voters for those previous pardons, Altgeld was uninterested in pardoning Prendergast for his slaying of the city's mayor.[4] This was particularly the case because the violent disorder of the then-ongoing Pullman Strike had created an appetite among Chicagoans to see harsh punishment for crime.[4]

Darrow and Harlan also met with Lieutenant Governor Joseph B. Gill to urge him to join them in supporting a pardon. Also traveling to meet Gill that day to persuade him to support a pardon was Brand Whitlock. Whitlocok and Darrow would meet and begin a friendship that day.[33][12] Gill was unpersuaded, arguing that Prendergast had been given fair and due process and a jury had found him sane.[12]

A request was made July 12, 1894 to federal judge Peter S. Grosscup (of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois) for a writ of habeas corpus and a request for a stay of execution.[7][30] in order to permit an appeal to be made to the Supreme Court of the United States under a claim that Prendergast's rights under the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment had been denied, pointing to Judge Horton having presented an opinion of his own concerning Prendergast's sanity during the trial and allowed certain evidence regarding the facts of the murder. The request also falsely claimed that Prendergast had not been permitted to speak on his own behalf.[7] In the hearing before Grosscup, strong arguments were made by Prendergast's lawyer. With hours left before Prendergast’s scheduled execution, Grosscup refused to stop the execution in a detailed opinion.[30] Grosscup opined that the Fourteenth Amendment was not applicable to "any particular trial but to the action of the Legislature and state polity."[7]

Execution of Prendergast

[edit]

Prendergast was hanged on July 13, 1894.[14] At 10 AM that morning, James H. Gilbert (sheriff of Cook County) came to the room where Prendergast had been held under guard since the previous night and read him the warrant for his execution. He was visited one last time by his brother John at 11 a.m., by which time hope for a last-minute reprieve from Governor Altgeld had dissipated. He was visited by a doctor at 11:30 and spent a brief time with a priest, declaring that there had been no malice in the killing of Mayor Harrison. Five minutes before his scheduled 11:45 execution, Stephen S. Gregory (one of Prendergast's attorneys) arrived and was allowed to shake his client's hand one last time and exchange a few words with him.[34]

A gallows had been constructed in the north corridor of the jail and seats placed between the row of cells along the north side and the high building wall.[34] Precaution was taken so that the apparatus would not malfunction, with the gallows being tested and inspected. Only six months prior, an incident had occurred in Chicago where the an execution was botched in a macabre manner that distressed some witnesses to the point of vomiting and fainting: the execution of murderer George H. Palmer had failed when the rope broke ion the first attempt, and Palmer had to be again hung in order to carry out the execution.[7]

About 500 ticketed witnesses assembled to watch the execution, which included the members of the jury which convicted Prendergast. Prisoners whose cells faced the corridor where the gallows were erected were removed from their cells 11:00 AM and brought to a location where the execution would not be visible to them.[7][34] At 11:11, attendees were instructed to extinguish any cigars.[7] At 11:43, the Cook County sheriff gave an order for Prendergast to be escorted to the gallows. He was then escorted by a number of deputy sheriffs and corrections officers. Also escorting Prendergast was Father Berry of the Cathedral of the Holy Name, who was on hand to administer the last rites of the Catholic Church.[7][34] A minute later, Prendergast arrived in the area where the gallows had been errected.[20]

When he got to the top of the platform, Prendergast briefly raised his hands, recognizing the crowd that gathered to view his execution.[7] Prendergast walked to the edge of the trap without assistance, where his hands were fastened. Although having previously planned to make a last statement to the crowd, he had been dissuaded by Father Berry, to whom he quietly delivered his last words, "I had no malice against anyone."[7][34]

The Chicago Daily News reported,

Great drops of perspiration glistened on [Prendgergast's] forehead, and he was white as the robe he wore. But he did not break down, by shutting his teeth tightly together so that his under jaw rigidly protruded, he awaited the end.[20]

Prendergast's feet, knees, and chest were bound with straps and a white shroud placed over him and he was taken onto the trap, where the noose was placed around his neck. A white muslin hood was placed over his head and the noose, obscuring both from view.[7][34]

A signal was given and at 11:48 the rope holding the heavy trap in place was cut. Prendergast's neck was broken by the six-foot drop and his body did not move after the fall.[34] His pulse was taken several times. Before the hanging, his pulse stood at 120 beats per minute (BPM).[7] Prendergast's heart continued to beat for about ten minutes after the trap was released.[34] It decreased to 58 BPM within a minute after the trap was released, but rose to 100 the second minute, 148 the third minute, 160 the fourth minute, before declining gradually thereafter to 100 BPM in the eighth minute. It stopped some time before the twelfth minute.[34] Five minutes later his body was taken down and placed in an awaiting coffin for burial.[34]

The Chicago Daily News reported,

Prendergast retained his nerve to the end and approached his doom without faltering. He made no dying speech on the scaffold and not a word was spoken from the time he stopped on the trap until the end. The drop fell at 11:47 [AM] and the body was cut down at 11:58.[20]

At 12:30 PM, Prendergast's hearse containing the coffin departed from the jail.[7] He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois in an unmarked grave located next to his father's grave.[7]

Aftermath

[edit]

Harrison's death created a void in Chicago city politics that allowed Roger Charles Sullivan and John Patrick Hopkins to grow their political machine within the Democratic Party. Harrison's son, Carter Harrison Jr., would run a rival faction of the city's Democratic Party, and would serve five terms as mayor, first being elected in 1897. The Sullivan-Hopkins political machine would, however, grow into the city's dominant political machine, later being headed by Richard J. Daley.[7]

After Harrison's assassination, George Bell Swift (a Republican) was appointed by the city council to serve as acting mayor in early November 1993.[35] In December, Democratic nominee John Patrick Hopkins defeated Bell in the special election to serve the remainder of Harrison's term.[36]

Harrison's namesake son, Carter Harrison Jr., would later also be elected mayor of Chicago five times.[37] Like Harrison Sr., Harrison Jr. served for two separate stretches of time, first in 1897–1905 and again in 1911–1915.[38] Harrison Jr. held similar politics to his father,[37]

Harrison's assassination inspired Chicago priest Casimir Zeglen to begin developing his design for a bulletproof vest.[39]

Harrison is one of two Chicago mayors to be assassination: the second being Anton Cermak, who was assassinated in 1933 while standing near (then-U.S. President-elect) Franklin D. Roosevelt at an event in Miami, Florida. That assassination is speculated to have possibly been meant to instead target the president-elect.[4] It coincidentally occurred only months before Chicago opened the gates of its second world’s exposition (the Century of Progress).

For many decades, Harrison's assassination was regarded as a significant and well-known moment in United States history. However, it has since fallen into relative obscurity.[7]

A bronze sculpture honoring Harrison is located in Chicago's Union Park. It was erected in 1907 using money raised by the Carter H. Harrison Memorial Association, which was formed in 1897. The sculpture was created by Frederick Hibbard, and was his first significant public artwork. The eight-foot tall sculpture depicts a standing Harrison, and is placed high atop a pedestal made of granite.[5]

The appellate litigation that followed Prendergast's conviction set significant new state and federal legal precedent.[30]

Thirty-three years later, Darrow would repurpose much of his rhetoric from Prendergast's case while defending murderers Leopold and Loeb.[4] He also wrote about Prendergast in his 1932 autobiography.[12] Prendergast's was the only individual that Darrow represented to be given a death sentence.[3][40][41]

Media depictions

[edit]On occasion, the assassination and its aftermath has been depicted in media. In the 1991 made-for-TV movie Darrow (which starred Kevin Spacey as Clarence Darrow) Prendergast's trial was featured and Prendergast was portrayed by actor Paul Klementowicz.[42] The assassination is one of the subplots in Erik Larson's 2003 best-selling non-fiction book The Devil in the White City.[43][44]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "'He Deserved to be Shot,' Said the Mayor's Assassin". Chicago Tribune. 9 October 1988. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Mayor Carter Henry Harrison III Biography". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt, John R. (28 October 2011). "Murder, mourning and a Chicago mayor". WBEZ.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Burke, Edward M. (2003). "Lunatics and Anarchists: Political Homicide in Chicago" (PDF). The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 92 (3–4).

- ^ a b "Carter Harrison Memorial". Chicago Park District. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Chicago, Classic (15 March 2020). "Murder in the Kentucky Colony". Classic Chicago Magazine. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp Morton, Richard Allen (2003). "A Victorian Tragedy: The Strange Deaths of Mayor Carter H. Harrison and Patrick Eugene Prendergast". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-). 96 (1): 6–36. ISSN 1522-1067. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

Also available at: "The story of Carter Harrison Sr., Chicago Mayor, Assassinated by Patrick Eugene Prendergast on October 28, 1893". The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2023. - ^ "General Registrar's Office". IrishGenealogy.ie. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Inishbofin Baptismal Register

- ^ Clifden 1865 Vol 14 page 81

- ^ a b c d Medical Society of the State of New York (1807–) (1895). Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of New York. Harvard University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hannon, Michael (2010). "Prendergast Case (1894)" (PDF). University of Minnesota Law Library. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "1893: Mayor Carter Harrison". Homicide in Chicago 1870–1930. Northwestern University. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ a b c d e f Mason, Joe (February 12, 2019). "The Mayor's Assassin". Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "1893: Mayor Carter Harrison". homicide.northwestern.edu. Northwestern University. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Schiff, Judith Ann (January 2019). "His Fair City". Yale Alumni Magazine. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Assassinated: Mayor Carter H. Harrison, of Chicago, Shot Down at his Residence by a Times Carrier". The Courier-Journal. Louisville. October 29, 1893. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d "Assassinated; Carter H. Harrison, Mayor of Chicago, Killed. Murderer in Custody". The New York Times. October 29, 1893.

- ^ a b c Martin, Alison (28 October 2021). "This Week in History: World's Fair ends in tragedy". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Alison (15 July 2021). "This Week in History: Mayor's murderer hanged". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Shot To Death". Ann Arbor Register. October 30, 1893. Retrieved 23 May 2024 – via Ann Arbor District Library.

- ^ a b c Boyle, Kevin (8 July 2011). "Clarence Darrow, Equal Opportunity Defender". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Witness for the Prosecution". Chicago Tribune. December 30, 1893. Retrieved 30 May 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Assassin is Indicted and Pleads not Guilty". Chicago Tribune. December 30, 1893. Retrieved 30 May 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Martin, Alison (29 October 2020). "This Week in History: Mayor Carter Harrison shot in mansion". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "Another Guiteau". Mt. Carmel Republican. November 3, 1893. Retrieved 27 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Guilty! Must Hang!". The Topeka Daily Capital. Vol. XV, no. 312. December 30, 1893. Retrieved 23 May 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Assasionation of Carter Harrison Chicago's Greatest Executive With an Interesting Review of His Eventful Life and Tributes of Respect to His Memory by Leading Men of the Nation (Illustrated)" (PDF). A. Theo. Patterson, Progressive Printer. 1894. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Tear-Dimmed Eyes and Bowed Heads; Funeral Services of the Late Carter Harrison". Salt Lake Herald. November 2, 1893. Retrieved 16 January 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography" (PDF). moses.law.umn.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "285. Becoming insane. excerpt from "The Revised Statues of the State of Illinois, Embracing All Laws of A General Nature In Force Jan. 1, 1893, with Notes and References to Judicial Decisions Construing Their Provisions." (Seventh Revised Edition, published by E.B. Meyers and Company in 1893, edited by George W. Cothran, LL. D. of the Chicago Bar Association)" (PDF). University of Minnesota Law Library. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "The Prendergast Case" (PDF). The Criminal Law Magazine a Reporter. XVI: 15–20. 1894. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Prendergast Case - 1894". librarycollections.law.umn.edu. Clarence Darrow Digital Collection (University of Minnesota Law Library). Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Assassin is Hanged". Chicago Daily Tribune. Vol. 53, no. 195. July 14, 1894. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mayor George Bell Swift Inaugural Address, 1893". www.chipublib.org. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Mayor John Patrick Hopkins Inaugural Address, 1893". www.chipublib.org. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ a b Bienen, Leigh (2012). "Harrison, Carter H. II". Northwestern University School of Law. The Life and Times of Florence Kelly. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Mayor Carter Henry Harrison IV Biography". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Simon, Scott (April 30, 2005). "A Priest's Early Quest to Create a Bulletproof Vest". Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Ray (July 13, 2015). "Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison's Assassin Patrick Eugene Prendergast was executed on this date in 1894". ChicagoNow. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Radeska, Tijana (July 30, 2017). "Famous lawyer Clarence Darrow, opposed to the death penalty, lost only one client to execution". The Vintage News.

- ^ "Darrow (TV Movie 1991) Full Cast & Crew". IMBD. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Summary and Analysis Part I: Chapter 4". Cliffs Notes. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Summary and Analysis Part II: Chapter 18". Cliffs Notes. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]

[[Category:1893 deaths|Harrison, Carter, Sr.]] [[Category:Carter Harrison Sr.]] [[Category:1893 in Chicago]] [[Category:October 1893 events in the United States]] [[Category:Murder in Chicago]] [[Category:Assassinations in the United States|Harrison, Carter]]