Diplomacy of the American Civil War

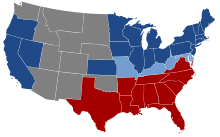

Light Blue: Slave states that did not secede

Red: Confederate States

Gray: Non-autonomous territories

The diplomacy of the American Civil War involved the relations of the United States and the Confederate States of America with the major world powers during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. The United States prevented other powers from recognizing the Confederacy, which counted heavily on Britain and France to enter the war on its side to maintain their supply of cotton and to weaken a growing opponent. Every nation was officially neutral throughout the war, and none formally recognized the Confederacy.

The major nations all recognized that the Confederacy had certain rights as an organized belligerent. A few nations did take advantage of the war. Spain reasserted control over its former colony in the Dominican Republic, but evacuated it in 1865.[1] More threatening was the Second French intervention in Mexico, under Emperor Napoleon III, which installed Maximilian I as a puppet ruler and aimed to negate American influence. France encouraged Britain to join in a policy of mediation, suggesting that both recognize the Confederacy,[2] while Abraham Lincoln warned that any such recognition was tantamount to a declaration of war. The British textile industry depended on cotton from the South, but it had stocks to keep the mills operating for a year and, in any case, the industrialists and workers carried little weight in British politics. Knowing a war would cut off vital shipments of American food, wreak havoc on the British merchant fleet, and cause an invasion of Canada, Britain and its powerful Royal Navy refused to join France.[3]

Historians emphasize that Union diplomacy proved generally effective, with expert diplomats handling numerous crises. British leaders had some sympathy for the Confederacy, but were never willing to risk war with the Union. France was even more sympathetic to the Confederacy, but it was threatened by Prussia and would not make a move without full British cooperation. Confederate diplomats were inept, or as one historian put it, "Poorly chosen diplomats produce poor diplomacy."[4] Other countries played a minor role. Russia made a show of support of the Union, but its importance has often been exaggerated.[5]

United States

[edit]

Lincoln's foreign policy was deficient in 1861, and he failed to garner public support in Europe. Diplomats had to explain that the United States was not committed to abolishing slavery, instead appealing to the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate spokesmen, on the other hand, were much more successful: ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, their commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy. Most European leaders were unimpressed with the Union's legal and constitutional arguments and thought it hypocritical that the U.S. should seek to deny to one of its regions the same sort of independence it won from Great Britain some eight decades earlier. Furthermore, since the Union was not committed to ending slavery, it struggled to persuade Europeans (especially Britons) that there was no moral equivalency between the rebels who established the United States in 1776 and the rebels who established the Confederate States in 1861. Even more importantly, the European aristocracy (the dominant factor in every major country) was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic."[6]

Another setback for the Union was that the United States had been alone among the world's maritime powers in not joining the 1856 Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law, which banned privateering, established that neutral ships with non-contraband goods were to be free from seizure in wartime, and that a naval blockade had to be effective to be legal (i.e. that a nation declaring a blockade must be able to enforce it in order for it to receive international acceptance). When the war began, the Confederacy commissioned privateers and used neutral ships as runners against the Union blockade of its ports. Attempts by the Lincoln administration to join the Paris Declaration then were rejected by Great Britain and France, who accused the Union of trying to use European navies to wage maritime war against the Confederates.[7]

For decades historians have debated who played the most important roles in shaping Union diplomacy. During the early 20th century, Secretary of State William H. Seward was seen as an Anglophobe who dominated a weak president. Lincoln's reputation was restored by Jay Monaghan who, in 1945, emphasized Lincoln's quiet effectiveness behind the scenes.[8] In 1976, Norman Ferris published a study of Seward's foreign policy, emphasizing his leadership role.[9] Lincoln continues to get high marks for his moral leadership in defining the meaning of the conflict in terms of democracy and freedom.[10][11] Numerous monographs have highlighted the leadership role of Charles Sumner as head of the Senate Foreign Relations committee,[12] and Charles Francis Adams as minister to the Court of St James's (United Kingdom).[13] Historians have studied Washington's team of hard-working diplomats,[14] financiers[15] and spies across Europe.[16][17]

Confederate failures

[edit]

Even the most avid promoters of secession had paid little attention to European affairs prior to 1860. The Confederates had for years uncritically assumed that "cotton is king"—that is, European countries had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton. However, this assumption was disproven during the war. Peter Parish argued that southern intellectual and cultural insularity proved fatal:

For years before the war the South had been building a wall around its perimeter, to protect itself from dangerous agitators and subversive ideas, and now those inside the wall could no longer see over the top, out to what lay beyond.[18]

Once the war began, the Confederacy pinned its hopes on foreign military intervention. However, the United Kingdom was not as dependent on Southern cotton as Confederate leaders believed; it had enough stock to last for over a year and developed alternative sources of cotton, most notably in India and Egypt. Great Britain was unwilling to risk war with the United States to acquire more cotton at the risk of losing large quantities of food imported from the North.[19][20] Meanwhile, the Confederate national government had lost control of its own foreign policy when cotton planters, factors, and financiers spontaneously decided to embargo shipments of cotton to Europe in early 1861. It was an enormously expensive mistake, depriving the Confederacy of millions of dollars in cash it would desperately need.[21]

The Confederate government sent delegations to Europe but they were ineffective in achieving their diplomatic aims.[19][22][23] The first commissioners named by CS President Jefferson Davis on February 1861 were William Lowndes Yancey to France and Britain, Pierre Adolphe Rost to Spain, and Ambrose Dudley Mann to Belgium and the Vatican, with journalist Edwin de Leon as their adviser and chief Confederate propagandist in Europe. Of these, Yancey came to be most identified with the "arrogant demands" of the Confederates in Europe. Later, James Murray Mason went to London and John Slidell to Paris, replacing Yancey. The envoys were unofficially interviewed but couldn't secure diplomatic recognition for the Confederacy. [24]

By early 1862, vice president Alexander H. Stephens and others considered Confederate diplomatic efforts such failures that he suggested withdrawing all agents and representatives from abroad and using the resources on the battlefield. Davis ignored this and appointed Judah P. Benjamin as secretary of state, who worked to forge a closer relationship with France, sell cotton at "remarkably low prices" and engage in arms purchases from French and British suppliers to link their commercial interests more closely with the Confederacy.[25] These Confederate purchasing agents, often working with blockade runners funded by British financiers, were more successful. James Dunwoody Bulloch was the mastermind behind the procurement of warships for the Confederate Navy.[26] Confederate propagandists, especially Henry Hotze and James Williams, were partly effective in mobilizing European public opinion. Hotze acted as a Confederate agent in the United Kingdom. His success was based on using liberal arguments of self-determination in favor of national independence, echoing the failed European revolutions of 1848. He also promised that the Confederacy would be a low-tariff nation in contrast to the high-tariff United States.[27] He consistently emphasized that the tragic consequences of cotton shortages for the industrial workers in Britain were caused by the Union blockade of Southern ports.[28][29]

In March 1862 James M. Mason teamed with several British politicians to push the government to ignore the Union blockade. Mason argued that it was only a "paper blockade", not enforceable, which by international law would make it illegal. However, most British politicians rejected this interpretation because it was counter to traditional British views on blockades, which Britain saw as one of its most effective naval weapons, as demonstrated by the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.[30]

In 1863, relations with Britain, France, and Spain soured after Benjamin banned foreign residents from communicating with their diplomats in Washington, followed by the expulsion of all diplomats from Confederate-held territory. The situation was so dismal that even De Leon called for the recall of all Southern agents from Europe.[25]

Confederate agent Father John B. Bannon was a Catholic priest who traveled to Rome in 1863 in a failed attempt to convince Pope Pius IX to grant diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy.[31] Bannon then moved on to Ireland, where he attempted to mobilize support for the Confederate cause and to neutralize the attempts of Union recruiters to enlist Irishmen into the Union army. Nevertheless, thousands of Irish emigrants volunteered to join the Union.[32]

Colonial Powers

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]

The British cabinet made the major decisions for war and peace and played a cautious hand, realizing the risk it would have on trade. Elite opinion in Britain tended to favor the Confederacy, while public opinion tended to favor the United States.[citation needed] Throughout the war, large-scale trade with the United States continued in both directions legally and illegally respectively. The Americans shipped grain to Britain while Britain sent manufactured items and munitions.[citation needed] Immigration continued into the United States as well. British trade with the Confederacy fell by 95%, with only a trickle of cotton going to Britain and hundreds of thousands of munitions slipping in by small blockade runners, most of them owned and operated by British interests.[citation needed]

Prime Minister Lord Palmerston was sympathetic to the Confederacy.[33] Although a professed opponent of the slave trade and slavery, he held a lifelong hostility towards the United States and believed a dissolution of the Union would weaken the United States – and therefore enhance British power – and that the Southern Confederacy "would afford a valuable and extensive market for British manufactures".[34]

Britain issued a proclamation of neutrality on 13 May 1861. The Confederacy was recognized as a belligerent, but it was too premature to recognize the South as a sovereign state since Washington threatened to treat recognition as a hostile action. Britain depended more on American food imports than Confederate cotton, and a war with the U.S. would not be in Britain's economic interest.[35] Palmerston ordered reinforcements sent to the Province of Canada because he was convinced the Union would make peace with the South and then invade Canada. He was very pleased with the Confederate victory at Bull Run in July 1861, but 15 months later he wrote that:

The American War ... has manifestly ceased to have any attainable object as far as the Northerns are concerned, except to get rid of some more thousand troublesome Irish and Germans. It must be owned, however, that the Anglo-Saxon race on both sides have shown courage and endurance highly honourable to their stock.[36]

Trent Affair

[edit]

A diplomatic crisis with the United States erupted over the "Trent Affair" in November 1861. The USS San Jacinto seized the Confederate diplomats James M. Mason and John Slidell from the British steamer RMS Trent. Public opinion in the United States celebrated the capture of the rebel emissaries.[37]

The US action provoked outrage in Britain. Palmerston called the action "a declared and gross insult", sent a note insisting on the release of the two diplomats, and ordered 3,000 troops to Canada. In a letter to Queen Victoria on 5 December 1861, he said that if his demands were not met, "Great Britain is in a better state than at any former time to inflict a severe blow upon and to read a lesson to the United States which will not soon be forgotten."[38] In another letter to his Foreign Secretary, he predicted war between Britain and the Union:

It is difficult not to come to the conclusion that the rabid hatred of England which animates the exiled Irishmen who direct almost all the Northern newspapers, will so excite the masses as to make it impossible for Lincoln and Seward to grant our demands; and we must therefore look forward to war as the probable result.[38]

However, the Queen's husband, Prince Albert, intervened. He worked to have Palmerston's note "toned down" to a demand for an explanation, and apology, for a mistake.[37]

Despite public approval of the seizure, Lincoln recognized that the United States could not afford to fight Britain, and that the modified note could be accepted.[37] The United States released the prisoners to the HMS Rinaldo in January 1862. Palmerston was convinced that the increased troops in Canada persuaded the United States to acquiesce.[39] However, the Lincoln administration did not apologize for the incident, nor forswear similar seizures happening in the future.[40]

The incident delayed Mason and Slidell's mission at a critical time when Europeans were discussing recognition, and by the time they arrived, "the emphasis of Confederate diplomacy had shifted from demands for recognition to denunciations of the blockade, a less effective issue for encouraging international intervention in support of the South".[40] In addition, the inability of the CSA to break the blockade or defend its port cities from occupation became a reason for non-intervention.[40]

"King Cotton"

[edit]The British Industrial Revolution was fueled by the expansion of textile production, which in turn was based mostly on cotton imported from the American South. The war cut off supplies, and by 1862, stocks had run out, and imports from Egypt and India could not make up the deficit. There was enormous hardship for the factory owners and especially the unemployed factory workers. The issues facing the British textile industry factored into the debate over intervening on behalf of the Confederacy in order to break the Union blockade and regain access to Southern cotton.[41][42]

Historians continue to be sharply divided on the question of British public opinion. One school argues that the aristocracy favored the Confederacy, while the abolitionist Union was championed by British liberals and radical spokesmen for the working class.[43] An opposing school argues that many British working men—perhaps a majority—were more sympathetic to the Confederate cause.[44] Finally, a third school emphasizes the complexity of the issue and notes that most Britons did not express an opinion on the matter. Local studies have demonstrated that some towns and neighborhoods took one position, while nearby areas took the opposite.[45] The most detailed study by Richard J. M. Blackett, noting that there was enormous variation across Britain, argues that the working class and religious nonconformists were inclined to support the Union, while support for the Confederacy came mostly from conservatives who were opposed to reform movements inside Britain and from high Church Anglicans.[46]

Humanitarian intervention

[edit]The question of British and French intervention was on the agenda in 1862. Palmerston was especially concerned with the economic crisis in the Lancashire textile mills, as the supply of cotton had largely run out and unemployment was soaring. He seriously considered breaking the Union blockade of Southern ports to obtain the cotton. But by this time the United States Navy was large enough to threaten the British merchant fleet,[47] and of course Canada could be captured easily.[48] A new dimension came when Lincoln announced the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. Many British leaders expected an all-out race war to break out in the American South, with so many tens or hundreds of thousands of deaths that humanitarian intervention was called for to prevent the threatened bloodshed. Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone opened a cabinet debate over whether Britain should intervene. Gladstone had a favorable image of the Confederacy and urged humanitarian intervention because of the staggering death toll, the risk of a race war, and the failure of the Union to achieve decisive military results.[citation needed]

In rebuttal, Secretary of War Sir George Cornewall Lewis opposed intervention as a high-risk proposition that could result in massive losses. Furthermore, Palmerston had other concerns, including a crisis concerning King Otto of Greece, in which Russia threatened to take advantage of the weaknesses of the Ottoman Empire. The Cabinet decided that the American situation was less urgent than the need to contain Russian expansion, so it rejected intervention. Palmerston rejected Napoleon III of France's proposal for the two powers to arbitrate the war and ignored all further efforts of the Confederacy to gain British recognition.[49][50][51]

Blockade runners

[edit]Several British financiers built and operated most of the blockade runners, spending hundreds of millions of pounds on them. They were staffed by sailors and officers on leave from the Royal Navy. When the U.S. Navy captured one of the blockade runners, it sold the ship and cargo as prize of war for the American sailors, then released the crew. During the war, British blockade runners delivered the Confederacy 60% of its weapons, 1/3 of the lead for its bullets, 3/4 of ingredients for its powder, and most of the cloth for its uniforms;[52] such act lengthened the Civil War by two years and cost 400,000 more lives of soldiers and civilians on both sides.[53]

CSS Alabama

[edit]

A long-term issue was the British shipyard (John Laird and Sons) building two warships for the Confederacy, especially the CSS Alabama, over vehement protests from the United States government. The controversy was resolved after the war in the Treaty of Washington which included the resolution of the Alabama Claims whereby Britain gave the United States $15.5 million after arbitration by an international tribunal for damages caused by British-built warships.[54]

Canada

[edit]The Union successfully recruited soldiers in British North America, and local officials tolerated the presence of Confederate agents despite Union protests. These agents planned attacks on U.S. cities and encouraged antiwar sentiment. In late 1864, Bennett H. Young led a small cavalry raid on St. Albans, Vermont, where he robbed three banks of $208,000 and killed one American. The raiders escaped back into Canada where they were arrested, but were released after a court ruled that they had followed military orders and extradition would be a breach of neutrality. The bounty was returned to Vermont.[55][56]

Slave trade

[edit]The British had long pressured the United States to increase their efforts to suppress the transatlantic slave trade, which both nations had abolished in 1807. Pressure from Southern states had neutralized this, but the Lincoln administration was now eager to sign up. In the Lyons–Seward Treaty of 1862, the United States gave Great Britain full authority to crack down on the transatlantic slave trade when carried on by American slave ships.[57]

France

[edit]

The Second French Empire under Napoleon III remained officially neutral throughout the Civil War and never recognized the Confederate States of America. It did recognize Confederate belligerency on 10 June 1861, one month after Britain.[58][24] The textile industry needed cotton, and Napoleon III had imperial ambitions in Mexico, which could be greatly aided by the Confederacy. The United States had warned that recognition meant war. France was reluctant to act alone without British collaboration, and the British rejected intervention. Emperor Napoleon III realized that a war with the U.S. without allies "would spell disaster" for France.[59] On the advice of its two Foreign Ministers Edouard Thouvenel and Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys, who did not lose sight of the national interest, Napoleon III adopted a cautious attitude and maintained diplomatically correct relations with Washington.[60] Half the French press favored the Union, while the "imperial" press was more sympathetic to the Confederacy. The public generally ignored the war, showing more interest in the Second French Intervention in Mexico.[61]

Spain

[edit]The Annexation of the Dominican Republic to Spain was partly due to the beginning of the American Civil War.[62] The end of the American Civil War in 1865 and the reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine by the United States, being no longer involved in internal conflict and possessing enormously expanded and modernized military forces as a result of the war, prompted the evacuation of Spanish forces back to Captaincy General of Cuba that same year.

Russia

[edit]Russian–Union relations were generally very cooperative. Alone among European powers, Russia offered oratorical support for the Union, largely due to the view that the United States served as a counterbalance to the British Empire.[63] Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia in 1861 and called for the emancipation of slaves worldwide, including the US South, Brazil, and Cuba.[64]

During the winter of 1861–1862, the Imperial Russian Navy sent two fleets to American waters to avoid them getting trapped if a war broke out with Britain and France. Many Americans at the time viewed this as an intervention on behalf of the Union, though some historians deny this.[65][66][67]

The Alexander Nevsky and the other vessels of the Atlantic squadron stayed in American waters for seven months, September 1863 to June 1864.[68] The Russian fleet was particularly appreciated in the thinly populated western states, where French-dominated Mexico was perceived as an additional threat to the Confederates.[64]

In 1863, Russia suppressed a large-scale insurrection in Poland during the January Uprising. Many Polish resistance leaders fled the country, and Confederate agents tried but failed to recruit them to come to America and join the Confederacy.[69]

In 1864, the Russian government rebuffed attempts by the Confederate agent Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar to meet with the Tsar in St. Peterburg.[64]

Netherlands

[edit]The Netherlands recognized Confederate belligerency. Due to the lack of Dutch territories in North America, however, this had little consequence.[70]

The Lincoln administration opened negotiations with the Dutch government regarding African American migration to the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America. Nothing came of the idea, and after 1864 it was abandoned.[71]

Latin America

[edit]Mexico

[edit]In 1861, Mexican conservatives looked to French leader Napoleon III to abolish the Republic led by liberal President Benito Juárez. The French expected that a Confederate victory would facilitate French economic dominance in Mexico. Napoleon helped the Confederacy by shipping urgently needed supplies through the ports of Matamoros, Mexico, and Brownsville, Texas. The Confederacy itself sought closer relationships with Mexico. Juarez turned them down, but the Confederates worked well with local warlords in northern Mexico, and with the French invaders.[72][73]

Realizing that Washington could not intervene in Mexico as long as the Confederacy controlled Texas, France invaded Mexico in 1861 and installed Austrian prince Maximilian I of Mexico as its puppet ruler in 1864. Owing to the shared convictions of the democratically elected governments of Juárez and Lincoln, Matías Romero, Juárez's minister to Washington, mobilized support in the U.S. Congress, and raised money, soldiers and ammunition in the United States for the war against Maximilian. Washington repeatedly protested France's violation of the Monroe Doctrine.

Once the Union won the war in spring 1865, the U.S. allowed supporters of Juárez to openly purchase weapons and ammunition and issued stronger warnings to Paris. Washington sent general William Tecumseh Sherman with 50,000 combat veterans to the Mexican border to emphasize that time had run out on the French intervention. Napoleon III had no choice but to withdraw his outnumbered army in disgrace. Emperor Maximilian refused exile and was executed by the Mexican government in 1867.[74]

Brazil

[edit]Though nominally neutral,[75] the Empire of Brazil was an unofficial ally of the Confederacy.[76] Emperor Pedro II of Brazil extended privileges to Confederate Navy ships, allowing them to secure supplies in Brazilian ports, which aided the Confederate naval effort of raiding Union vessels in the South Atlantic.[77] The imperial government granted the Confederacy a "belligerent" status, refusing demands by the Union to treat Confederate vessels as pirates, and ignored diplomatic protests from Washington demanding the forcible removal, by a U.S. warship, of the CSS Sumter at a port in Maranhão on September 6, 1861. Similarly, in 1863 the U.S. ambassador to Brazil, James Watson Webb, exchanged correspondence with the Brazilian Foreign Minister about two Confederate steamers, the CSS Alabama and the CSS Georgia, that had been receiving provisions and repairs at ports in Pernambuco and Bahia, a situation that Webb described as "a gross breach of neutrality".

After the war, thousands of Confederates emigrated to Brazil on the invitation of Pedro II and subsidized by the Brazilian government.[76]

Haiti

[edit]Despite sharing trade and informal relations since independence, the United States refused to recognize Haiti as a country for most of the 19th century. The main reason was Southern fears that Haiti would become an example and rallying point for a slave rebellion, as Haiti had originated in one, as well as a refusal to recognize the dignity of any black person as an ambassador.[78]

President Fabre Geffrard invited African Americans to immigrate in 1858,[79] wishing to incorporate American developments in agriculture.[78] In 1861, Frederick Douglass visited the country and spoke favorably of it as a destination for freedmen, but the beginning of the war precluded this. Although thousands had moved successfully to Haiti earlier in the century, the roughly one thousand who moved in this time found conditions much worse than expected, and after suffering from smallpox and yellow fever many returned to the United States.[79]

Following the departure of most Southerners from the House of Representatives, the United States recognized Haiti on 5 June 1862. Lincoln hoped that relations with Haiti would entice African Americans to move there, and that this would reduce race tensions in the postwar United States.[78] The first appointed Commissioner and Consul General was Benjamin F. Whidden. Trade increased after recognition, and in 1864 the port of Gonaïves alone shipped over 250,000 pounds of cotton to the United States.[78]

Asia and the Pacific

[edit]Hawaii

[edit]King Kamehameha IV declared Hawaii's neutrality on August 26, 1861.[80][81] However, many Native Hawaiians and Hawaii-born Americans (mainly descendants of American missionaries), abroad and in the islands, enlisted in the military regiments of various states in the Union and the Confederacy.[82] Many Hawaiians sympathized with the Union because of Hawaii's ties to New England through its missionaries and whaling industries, and the opposition of many to the institution of slavery, which the Constitution of 1852 had officially outlawed.[83][84][85]

Japan

[edit]The Tokugawa Shogunate did not participate in the American Civil War. American representation in Japan remained loyal to the Union, and the Confederacy never tried to establish relations with the country. However, the war indirectly affected the fledging relations between the two countries and with third parties.[86]

European rivalry

[edit]

According to historian George M. Brooke, the United States was set to play a significant role in the creation of the Imperial Japanese Navy, but the outbreak of the Civil War prevented it, and the Japanese turned to the British Royal Navy for assistance instead.[87] American prestige in Japan, high from the 1853 Perry Expedition and the early arrival of American missionaries, declined in 1862-1863 due to the war straining communications, lack of American military presence in Japan, and Anglo-French threats to recognize the Confederacy, which stoke tensions between Americans and Europeans and were perceived as a weakness by the Japanese. The American consul in Kanagawa, Colonel Fisher, blamed the diplomacy of the French Jesuit Mermet de Cachon the most, perceiving the British as a lesser threat represented only by their global naval and military power.[88] In contrast, the American minister to Japan Robert H. Pruyn told British Captain John Moresby that "we hate England", and "I only hope... to see the day when we shall have settled with the South, and can take England by the throat for all the insults and sneers she has heaped on us", even though the American legations were dependent on British protection against increasing anti-foreign sentiment in Japan, and the British agreed to transport Pruyn between Yokohama and Edo free of charge.[89] The consul in Hakodate, E.E. Rice, asked for a letter of marque to turn his ship The One into a privateer if war with Britain and France broke out.[88]

Shimonoseki conflict

[edit]In parallel, the conflict between the aperturist Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi and the isolationist Sonnō jōi movement reached pre-bellic status by early 1863. On February, the Shogun's minister of foreign affairs told Pruyn that Tokugawa feared civil war; the daimyo of Satsuma and Chōshū were most hostile to foreigners and influencing Emperor Kōmei. When asked about the US's reaction to war in Japan, Pruyn said that they would support the Shogun in any way they could, and that foreign powers would be justified to act against the hostile daimyo in self-defence. Soon after, the Emperor summoned the Shogun to Kyoto for the first time since 1634, where he remained for months, while attacks against foreigners multiplied. On May 25, the American legation in Edo was destroyed by fire. The cause was not identified but the Shogun's representative advised Pruyn to move to Yokohama for his own safety.[90]

Pruyn's request of naval protection from Washington was unheeded, but he got an answer from the USS Wyoming, which had been sent to Asia to pursue the CSS Alabama and was fortuitously in Hong Kong.[90] On June 24, the Shogun, on the order of the Emperor, formally demanded all foreigners to leave Japan. However, the Shogun was himself against the order and his representative told Pruyn to ignore it, reassuring him that the Shogun would protect the foreign legations until it was rescinded. Nevertheless, Pruyn replied that the order was a breach of the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce and tantamount to a declaration of war.[90]

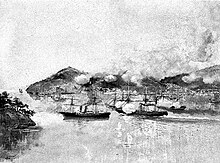

Two days later, Chōshū forces closed the Shimonoseki Straits to foreign shipping and attacked the American merchant S.S. Pembroke. Pruyn demanded "satisfaction" from the Shogun, saying the incident "if justified by the government, constituted war; if disavowed, were acts of piracy."[90] Without waiting for approval from Washington, the Wyoming sailed to Shimonoseki and on 16 July engaged the daimyo's three ships while under fire from coastal artillery, sinking two and damaging the other, along with one battery,[91] before retiring due to lacking depth charts of the area. Pruyn reiterated that "the attack on the Pembroke was an act of piracy, which required immediate punishment." In America, the attack was approved by Congress, by Abraham Lincoln in his 1863 State of the Union address, Secretaries of State Seward and of the Navy Gideon Welles, as a vindication of the honor of the American flag and the "enlightened and liberal policy" of the Shogun against "the perverse opposition of the hereditary aristocracy of the Empire". Only decades later, historian Tyler Dennett would rebuke the incident as "un-American when judged by the entire American record in Asia."[90]

In any case, the action of the Wyoming was immediately dwarfed by the French burning of Shimonoseki on 24 July and the British bombardment of Kagoshima in August, both in response to Japanese attacks against them. One year later, a fleet of British, French, and Dutch warships, accompanied by one American man-of-war as a sign of support, destroyed Chōshū's military capability at Shimonoseki and forced the daimyo to capitulate.[91] The Shogun was satisfied because, while the foreigners had resorted to violence to defend the treaty rights, it had been against Chōshū, an enemy of the Shogunate, and tacitly in support of the Shogun's own policy. The Japanese accepted the indemnity demanded by the Pembroke (considered excessive even by Pruyn) and paid $12,000 on September 5, 1864.[90]

British and French Marines also occupied Yokohama between 1863 and 1875, further decreasing American influence.[87] To counter this, Fisher requested unsuccessfully that a fleet and marine garrison be stationed at Yokohama, on par with those maintained by the French and British.[88]

Siam

[edit]

On 14 February 1861 (the last month of the Buchanan administration), King Mongkut of Siam wrote a diplomatic letter addressed to the President of the United States in Washington, D.C., expressing his desire to have friendly relations with the country. The letter was accompanied by a photograph of Mongkut with one of his daughters, a sword, and two elephant tusks as diplomatic gifts. In the text, Mongkut mentioned that he had been informed of the introduction of the non-native dromedary camel as a beast of burden used by the United States Camel Corps, and said he was willing to cooperate if the United States wished to do the same with the Asian elephant. Per the proposal, the United States would provide a vessel capable of transporting elephants across the ocean, and Siam would forward one or two pairs of young elephants at a time, which would be released in American forests, allowed to multiply, and subsequently captured to haul cargo in forested areas without roads.[92]

Elephants are not true domestic animals because they couldn't be bred in captivity until recently, and the nations of southern Asia were historically dependent on the capture and trade of wild-born elephants for use as work animals.[93] The capture and sale of live elephants to other countries had been a royal monopoly in Siam for centuries before Mongkut's offer was made.[94]

Though the letter was given to the American Consul in Siam, no ship was allocated to deliver it directly to Washington, and it was expected to be substantially delayed as it changed ships from port to port.[92] Lincoln wrote a reply on 3 February 1862, accepting the gifts on behalf of the American people, but politely declined living elephants under the reasoning that the geography of the United States was not favorable for their multiplication, and the steam engine was sufficient to cover its transportation needs. This "humorous event" has been misrepresented in later times as Mongkut offering war elephants to be deployed in the American Civil War.[95] The Camel Corps that prompted Mongkut's offer was abandoned during the war, partly because its main proponent had been Jefferson Davis during his time as Secretary of War in the Franklin Pierce administration.[96][97]

Other countries

[edit]Prussia

[edit]Preoccupied with trying to unify the various German states under its banner, Prussia did not participate in the American Civil War. However, several members of the Prussian military served as officers and enlisted men in both armies, just as numerous men who had previously emigrated to the United States. Also, official military observers were sent to North America to observe the tactics of both armies, which were later studied by future military leaders of Prussia and then the unified Germany.

Prussia recognized Confederate belligerency, but the lack of Prussian overseas territories made this mean very little.[70]

Among the effects that Prussia had on the war was the new saddle used by the Union cavalry: Union General George McClellan had studied Prussian saddles and used them as a basis for his McClellan saddle.[98]

Austria

[edit]Austria pursued amicable relations with the Union throughout the American Civil War. Reminded of the recent Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire, Austria opposed revolutionary efforts on principle, which drove them away from the Confederacy. The Austrian Foreign Minister officially stated three days after the outbreak of the American war that "Austria hoped to see the United States reunited since she was not inclined to recognize de facto Governments anywhere." Assuming the war would end shortly, Austria hoped that through a friendly relationship with the Union, the United States would later help them to protect their maritime neutral trading rights, which they feared would be violated in the case of a European war. In 1864, Napoleon III installed Archduke Maximilian of Austria, brother to the Emperor of Austria, as the monarch in French-controlled Mexico. Austria made efforts to separate itself from the French venture, and when Maximilian assumed the throne in Mexico, the Emperor of Austria forced him to renounce his claim to the Austrian crown. These actions satisfied Union diplomats, who disapproved of the European intervention in North America, allowing the United States and Austria to maintain friendly relations through the close of the Civil War.[99]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]The Ottoman Empire strongly favored the Union. It signed a trade deal with the Union and considered Confederate ships as pirate ships, banning them from entering its waters. The Ottoman Empire stood to benefit from the Union's blockade of the Confederate ports, with the cotton industry of the empire (chiefly Egypt) becoming Europe's largest supplier of cotton as a result.[100]

Italy

[edit]The Italian military leader Giuseppe Garibaldi was one of the most famous people in Europe as a proponent of liberty and republican government; he strongly favored the Union. Early in the war, Washington sent a diplomat to invite him to become an American general. Garibaldi declined the offer because he would not be given supreme power over all the armies, and because the United States was not yet committed to abolishing slavery. Historians agree that he was too independent in thought and deed to have worked smoothly with the U.S. government.[101]

World perspective

[edit]Historian Don H. Doyle has argued that the Union victory had a major impact on the course of world history.[102] The Union victory energized popular democratic forces. A Confederate victory, on the other hand, would have meant a new birth of slavery, not freedom. Historian Fergus Bordewich, following Doyle, argues that:

The North's victory decisively proved the durability of democratic government. Confederate independence, on the other hand, would have established an American model for reactionary politics and race-based repression that would likely have cast an international shadow into the twentieth century and perhaps beyond.[103]

Postwar adjustments

[edit]Union relations with Britain (and Canada) were tense; Canada was seen at fault in the St. Albans Raid into Vermont in 1864. The Canadian government captured the Confederates who robbed a bank and killed an American, then released them, angering American opinion.[104] London forced the Canadian Confederation in 1867, in part as a way to meet the American challenge without relying on support from the British military.[105]

Irish Republican militants, known as the Fenians, were permitted to openly organize on U.S. soil immediately following the war. Between 1866 and 1871 the Fenians launched several unsuccessful raids into Canada, American authorities continued to more or less look the other way. The arbitration of the Alabama Claims in 1872 provided a satisfactory reconciliation; the British paid the United States $15.5 million for the economic damage caused by Confederate warships purchased from it.[106] Congress purchased Alaska from Russia in the Alaska Purchase in 1867, but otherwise rejected proposals for any major expansions, such as the proposal by President Ulysses Grant to acquire Santo Domingo.[107]

See also

[edit]- Foreign enlistment in the American Civil War

- History of U.S. foreign policy

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Timeline of United States diplomatic history

Notes

[edit]- ^ James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 70.4 (1980): 1–121. in JSTOR

- ^ Lynn M. Case, and Warren E. Spencer, The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy (1970)

- ^ Kinley J. Brauer, "British Mediation and the American Civil War: A Reconsideration," Journal of Southern History, (1972) 38#1 pp. 49–64 in JSTOR

- ^ Hubbard, Charles M. (2013). The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572330924.

- ^ Tarply, Webster G. (2013). Russia's Participation in the U.S. Civil War. Washington D.C.: CSPAN.

- ^ Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An international history of the American Civil War (2014) pp 8 (quote), 69–70

- ^ Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press, pg. 47.

- ^ Jay Monaghan, Diplomat in carpet slippers: Abraham Lincoln deals with foreign affairs (1945).

- ^ Norman B. Ferris, Desperate Diplomacy: William H. Seward's Foreign Policy, 1861 (1976).

- ^ Kinley J. Brauer, "The Slavery Problem in the Diplomacy of the American Civil War," Pacific Historical Review (1977) 46#3 pp. 439–469 in JSTOR

- ^ Howard Jones, Abraham Lincoln and a new birth of freedom: the union and slavery in the diplomacy of the civil war (2002).

- ^ Donald, David Herbert (1970). Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781504034043.

- ^ Martin Duberman, Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1886 (1960).

- ^ Francis M. Carroll, "Diplomats and the Civil War at Sea" Canadian Review of American Studies 40#1 (2010) pp 117–130.

- ^ Jay Sexton, Debtor Diplomacy: Finance and American Foreign Relations in the Civil War Era, 1837–1873 (2005).

- ^ David Hepburn Milton, Lincoln's Spymaster: Thomas Haines Dudley and the Liverpool Network (2003.

- ^ Harriet Chappell Owsley, "Henry Shelton Sanford and Federal Surveillance Abroad, 1861–1865," Mississippi Valley Historical Review 48#2 (1961), pp. 211–228 in JSTOR

- ^ Peter J. Parish (1981). The American Civil War. Holmes & Meier Publishers. p. 403. ISBN 9780841901971.

- ^ a b Blumenthal (1966)

- ^ Lebergott, Stanley (1983). "Why the South Lost: Commercial Purpose in the Confederacy, 1861–1865". Journal of American History. 70 (1): 61. doi:10.2307/1890521. JSTOR 1890521.

- ^ Jay Sexton, "Civil War Diplomacy". In Aaron Sheehan-Dean, ed., A Companion to the US Civil War (2014): 745–746.

- ^ Jones, Jones (2009). Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations.

- ^ Owsley, Frank (1959). King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America.

- ^ a b Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press. p. 58.

- ^ a b Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press. pp. 73-77.

- ^ Sexton, "Civil War Diplomacy". 746.

- ^ Marc-William Palen, "The Civil War's Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate and the Confederacy's Free Trade Diplomacy". Journal of the Civil War Era 3#1 (2013): 35–61.

- ^ Andre Fleche, Revolution of 1861: The American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict (2012) p. 84.

- ^ Stephen B. Oates, "Henry Hotze: Confederate Agent Abroad". Historian 27.2 (1965): 131–154.

- ^ Charles M. Hubbard, "James Mason, the 'Confederate lobby' and the blockade debate of March 1862". Civil War History 45.3 (1999): 223–237.

- ^ David J. Alvarez, "The Papacy in the Diplomacy of the American Civil War". Catholic Historical Review 69.2 (1983): 227–248.

- ^ Philip Tucker, "Confederate Secret Agent in Ireland: Father John B. Bannon and His Irish Mission, 1863–1864". Journal of Confederate History 5 (1990): 55–85.

- ^ Kevin Peraino, "Lincoln vs. Palmerston" in his Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power (2013) pp 120–169.

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 552.

- ^ Thomas Paterson; J. Garry Clifford; Shane J. Maddock (2009). American Foreign Relations: A History to 1920. Cengage Learning. p. 149. ISBN 9780547225647.

- ^ Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 559.

- ^ a b c Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's Indispensable Man (2012) ch. 11

- ^ a b Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 554.

- ^ Kenneth Bourne, "British Preparations for War with the North, 1861–1862". The English Historical Review 76# 301 (1961) pp 600–632

- ^ a b c Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press, p. 67.

- ^ Sven Beckert, "Emancipation and empire: Reconstructing the worldwide web of cotton production in the age of the American Civil War". American Historical Review 109#5 (2004): 1405–1438.

- ^ Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism (2014) pp. 241–273.

- ^ Duncan Andrew Campbell (2003). English Public Opinion and the American Civil War. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780861932634.

- ^ Mary Ellison, Support for Secession: Lancashire and the American Civil War (1972).

- ^ Duncan Andrew Campbell, English Public Opinion and the American Civil War (2003).

- ^ Richard J. M. Blackett, Divided Hearts: Britain and the American Civil War (2001).

- ^ Warren, Gordon H. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas, p. 154 (1981). ISBN 0-930350-12-X.

- ^ Bourne, Kenneth. "British Preparations for War with the North, 1861–1862", The English Historical Review, Vol. 76, No. 301 (Oct 1961) pp. 600–605 in JSTOR.

- ^ Niels Eichhorn, "The Intervention Crisis of 1862: A British Diplomatic Dilemma?" American Nineteenth Century History 15#3 (2014) pp. 287–310.

- ^ Frank J. Merli and Theodore A. Wilson. "The British Cabinet and the Confederacy: Autumn, 1862". Maryland Historical Magazine (1970) 65#3 pp. 239–262.

- ^ Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 559.

- ^ Gallien, Max; Weigand, Florian (December 21, 2021). The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling. Taylor & Francis. p. 321. ISBN 9-7810-0050-8772.

- ^ David Keys (June 24, 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- ^ Frank J. Merli, The Alabama, British Neutrality, and the American Civil War (2004).

- ^ Adam Mayers, Dixie and the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the Union (2003) online review

- ^ "Gen. Young, lawyer and soldier, dies". The Courier-Journal. February 24, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Conway W. Henderson, "The Anglo-American Treaty of 1862 in Civil War Diplomacy". Civil War History 15.4 (1969): 308–319.

- ^ Kevin Peraino, "Lincoln vs. Napoleon" in Peraino, Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power (2013) pp. 224–295.

- ^ Howard Jones (1999). Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press. p. 183. ISBN 0803225822.

- ^ Stève Sainlaude, "France and the American Civil War. A diplomatic history" (2019) pp. 185–186.

- ^ Lynn M. Case, and Warren E. Spencer, The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy (1970)

- ^ Santo Domingo under Spanish sovereignty (1858-1865) (in Spanish)

- ^ Norman A. Graebner. "Northern Diplomacy and European Neutrality". Why the North Won the Civil War, ed. David Donald (1960), pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press, p. 59

- ^ Thomas A. Bailey. "The Russian Fleet Myth Re-Examined". Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 1 (June 1951), pp. 81–90

- ^ Howard I. Kushner, "The Russian Fleet and the American Civil War: Another View." 'The Historian 34.4 (1972): 633-649.

- ^ C. Douglas Kroll, Friends in Peace and War: The Russian Navy's Landmark Visit to Civil War (Potomac Books, 2007).

- ^ Davidson, Marshall B. (June 1960). "A ROYAL WELCOME for the RUSSIAN NAVY". American Heritage Magazine. 11 (4): 38. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ Krzysztof Michalek. "Diplomacy of the Last Chance: The Confederate Efforts to Obtain Military Support from the Polish Emigration Circles". American Studies (1987), Vol. 6, pp. 5–16.

- ^ a b Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press, p. 72.

- ^ Michael J. Douma. "The Lincoln Administration's Negotiations to Colonize African Americans in Dutch Suriname". Civil War History 61#2 (2015): 111–137.

- ^ J. Fred Rippy. "Mexican Projects of the Confederates". Southwestern Historical Quarterly 22#4 (1919), pp. 291–317

- ^ Kathryn Abbey Hanna, "The Roles of the South in the French Intervention in Mexico". Journal of Southern History 20#1 (1954), pp. 3–21

- ^ Robert Ryal Miller. "Matias Romero: Mexican Minister to the United States during the Juarez-Maximilian Era". Hispanic American Historical Review (1965) 45#2 pp. 228–245.

- ^ Don H. Doyle, ed. (2017). American Civil Wars: The United States, Latin America, Europe, and the Crisis of the 1860s. University of North Carolina Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781469631103.

- ^ a b Alan P. Marcus (2021). Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil. University of Nebraska Press. p. 59. ISBN 9781496224156.

- ^ Hopperstad, Shari Estill (1963). Confederate exiles to Brazil (Thesis). University of Montana. p. 5-6.

- ^ a b c d Plummer, B. G. (1992). Haiti and the United States: The Psychological Moment. University of Georgia Press, pp. 40-45

- ^ a b Bowen, W. H. (2011). Spain and the American Civil War. University of Missouri Press, p. 95.

- ^ Kuykendall 1953, pp. 57–66.

- ^ Forbes 2001, pp. 298–299.

- ^ National Park Service 2015, pp. 130–163.

- ^ Vance, Justin W.; Manning, Anita (October 2012). "The Effects of the American Civil War on Hawaiʻi and the Pacific World". World History Connected. 9 (3). Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

- ^ Manning & Vance 2014, pp. 145–170.

- ^ Smith, Jeffrey Allen (August 13, 2013). "The Civil War and Hawaii". The New York Times: Opinionator. New York.

- ^ Ion, H. (2010). American Missionaries, Christian Oyatoi, and Japan, 1859-73. UBC press, 440 pages.

- ^ a b Ibid, pgs. 17-18.

- ^ a b c Ibid, pgs. 45-46.

- ^ Ibid, pg. 51

- ^ a b c d e f Ross, F. E. (1934). The American Naval Attack on Shimonoseki in 1863. Chinese Soc. & Pol. Sci. Rev., Vol. 18, pgs. 146-155.

- ^ a b Kodet, R. (2021). Great Britain, the Great Powers, and the Shimonoseki Incident. Revista Română de Studii Eurasiatice, n. 17(1+ 2), pgs. 261-282.

- ^ a b Young, D., & Williams, B. (2007). Dear Mr. President: letters to the Oval Office from the files of the National Archives. National Geographic Books, pg. 184.

- ^ Roots, C. (2007). Domestication. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 232 pages.

- ^ na Pombejra, D. (2015). Catching and selling elephants. In Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350–1800, pgs. 192-210.

- ^ "Lincoln Rejects the King of Siam's Offer of Elephants". American Battlefield Trust. February 2, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Carroll, Charles C. (1903). "The Government's Importation of Camels: A Historical Sketch". Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Animal Industry, United States Department of Agriculture, Volume 20. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agtriculture. pp. 391–409. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Lammons, Bishop F. (1958). Carroll, H. Bailey (ed.). "Operation Camel". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 61. Texas State Historical Association: 20–50. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ O'Brien, Cormac (2007). Secret Lives of the Civil War: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the War Between the States. Quirk Books. ISBN 1-59474-138-7.

- ^ Kaufman, Burton Ira (May 1964). Austro-American Relations, 1861–1866 (PDF). Houston, Texas: Rice University.

- ^ Erhan, Cagri (2002). "Turkish Approach to the American Civil War (1861-1865)". Conference: Coming to the Americas: The Eurasian Military Impact on the Development of the Western Hemisphere.

- ^ R. J. Amundson, "Sanford and Garibaldi". Civil War History 14#.1 (1968): 40–45.

- ^ Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (2014)

- ^ Fergus M. Bordewich, "The World Was Watching: America's Civil War slowly came to be seen as part of a global struggle against oppressive privilege". The Wall Street Journal (February 7–8, 2015)

- ^ John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall. Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies (4th ed. 2008) pp. 36–37.

- ^ Garth Stevenson (1997). Ex Uno Plures: Federal-Provincial Relations in Canada, 1867–1896. McGill–Queen's Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780773516335.

- ^ Maureen M. Robson. "The Alabama Claims and the Anglo-American Reconciliation, 1865–71". Canadian Historical Review (1961) 42#1 pp. 1–22.

- ^ Jeffrey W. Coker (2002). Presidents from Taylor Through Grant, 1849–1877: Debating the Issues in Pro and Con Primary Documents. Greenwood. pp. 205–6. ISBN 9780313315510.

Works cited

[edit]- Forbes, David W., ed. (2001). Hawaiian National Bibliography, Vol 3: 1851–1880. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2503-4. OCLC 314293370.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1953). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1854–1874, Twenty Critical Years. Vol. 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4. OCLC 47010821.

- Manning, Anita; Vance, Justin W. (2014). "Hawaiʻi at Home During the American Civil War". Hawaiian Journal of History. 47. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 145–170. hdl:10524/47259.

- Shively, Carol A., ed. (2015). "Pacific Islanders and the Civil War". Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War. Washington, D. C.: National Park Service. pp. 130–163. ISBN 978-1-59091-167-9. OCLC 904731668.

Further reading

[edit]General

[edit]- Ayers, Edward L. "The American Civil War, Emancipation, and Reconstruction on the World Stage." OAH Magazine of History 20.1 (2006): 54–61.

- Brauer, Kinley J. "The Slavery Problem in the Diplomacy of the American Civil War." Pacific Historical Review 46.3 (1977): 439–469. in JSTOR

- Brauer, Kinley. "Civil War Diplomacy." Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy (2001): 1:193+; short summary by expert

- Doyle, Don H. "The Global Civil War." in Aaron Sheehan-Dean ed., A Companion to the US Civil War (2014): 1103–1120.

- Ferris, Norman B. Desperate Diplomacy: William H. Seward’s Foreign Policy, 1861 (1976).

- Fry, Joseph A. Lincoln, Seward, and US Foreign Relations in the Civil War Era (2019).

- Jones, Howard. Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (2010) online

- Monaghan, Jay. Diplomat in Carpet Slippers (1945), Popular study of Lincoln the diplomat online

- Peraino, Kevin. Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power (2013). online

- Prior, David M., et al. "Teaching the Civil War Era in Global Context: A Discussion." The Journal of the Civil War Era 5.1 (2015): 97–125. excerpt

- Sexton, Jay. "Civil War Diplomacy." in Aaron Sheehan-Dean ed., A Companion to the US Civil War (2014): 741–762.

- Sexton, Jay. "Toward a synthesis of foreign relations in the Civil War era, 1848–77." American Nineteenth Century History 5.3 (2004): 50–73.

- Sexton, Jay. Debtor Diplomacy: Finance and American Foreign Relations in the Civil War Era, 1837–1873 (2005).

- Taylor, John M. William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand (Potomac Books, 1996).

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. William Henry Seward (1967).

- Warren, Gordon H. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas (1981).

Confederacy

[edit]- Beckert, Sven. "Emancipation and empire: Reconstructing the worldwide web of cotton production in the age of the American Civil War." American Historical Review 109.5 (2004): 1405–1438. in JSTOR

- Blumenthal, Henry. "Confederate diplomacy: Popular notions and international realities." Journal of Southern History 32.2 (1966): 151–171. in JSTOR

- Cullop, Charles P. Confederate Propaganda in Europe, 1861–1865 (1969).

- Crawford, Martin. Old South/New Britain: Cotton, Capitalism, and Anglo-Southern Relations in the Civil War Era (Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2007).

- Oates, Stephen B. "Henry Hotze: Confederate Agent Abroad." Historian 27.2 (1965): 131–154. in JSTOR

- Marler, Scott P. "'An Abiding Faith in Cotton': The Merchant Capitalist Community of New Orleans, 1860–1862." Civil War History 54#3 (2008): 247–276. online

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence. King Cotton Diplomacy (1931), The classic history; full text online; also see online review

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence. "The Confederacy and King Cotton: A Study in Economic Coercion," North Carolina Historical Review 6#4 (1929), pp. 371–397 in JSTOR; summary

- Thompson, Samuel Bernard. Confederate purchasing operations abroad (1935).

- Waite, Kevin. West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire (UNC Press Books, 2021), prewar goals.

- Young, Robert W. Senator James Murray Mason: Defender of the Old South (1998).

- Zvengrowski, Jeffrey. Jefferson Davis, Napoleonic France, and the Nature of Confederate Ideology, 1815–1870 (2019) online review

International perspectives

[edit]- American Civil Wars: A Bibliography. A comprehensive bibliography of the United States Civil War's international entanglements and parallel civil strife in the Americas in the 1860s.

- Blumenthal, Henry. "Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities," Journal of Southern History, Vol. 32, No. 2 (May 1966), pp. 151–171 in JSTOR

- Boyko, John. Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. ISBN 978-0-307-36144-8.

- Cortada, James W. "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 70#4 (1980): 1–121.

- Doyle, Don H. The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (2014) online review

- Fleche, Andre. Revolution of 1861: The American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict (2012).

- Hyman, Harold Melvin. Heard Round the World; the Impact Abroad of the Civil War. (1969).

- Jones, Howard. Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. (U of Nebraska Press, 1999).

- Jordan, Donaldson, and Edwin J. Pratt. Europe and the American Civil War (2nd ed. 1969).

- Klees, June. "External Threats and Consequences: John Bull Rhetoric in Northern Political Culture during the United States Civil War." Advances in the History of Rhetoric 10#1 (2007): 73–104.

- Mahin, Dean B. One War at a Time: The International Dimensions of the American Civil War (Potomac Books, 1999).

- May, Robert E., ed. The Union, the Confederacy, and the Atlantic Rim. (2nd ed. 2013).

- Mayers, Adam. Dixie and the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the Union (2003) online review

- Saul, Norman E. Distant Friends: The United States and Russia, 1763–1867 (1991).

- Winks, Robin. Canada and the United States: The Civil War Years (1960).

Britain

[edit]- Adams, Ephraim D. Great Britain and the American Civil War (2 vols. 1925), old classic. vol 1 online; also see vol 2 online

- Bennett, John D. The London Confederates: The Officials, Clergy, Businessmen and Journalists Who Backed the American South During the Civil War. (McFarland, 2012) ISBN 978-0-7864-6901-7.

- Berwanger, Eugene. The British Foreign Service and the American Civil War (2015).

- Blackett, R. J. M. Divided Hearts: Britain and the American Civil War (2001) online.

- Campbell, Duncan Andrew. English Public Opinion and the American Civil War (2003).

- Crook, D. P. The North, The South, and the Powers, 1861–1865 (1974), focus on Britain and Canada.

- Duberman, Martin B. Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1886 (1960), U.S. minister in Britain. online

- Ellison, Mary. Support for Secession: Lancashire and the American Civil War (1972); role of cotton mill workers.

- Ferris, Norman B. The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis (1977).

- Foreman, Amanda. A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War (2011). online; New York Times Bestseller

- Fuller, Howard J. Clad in iron: The American Civil War and the challenge of British naval power (Greenwood, 2008).

- Jones, Howard. Union in Peril: The Crisis Over British Intervention in the Civil War (1992).

- Long, Madeline. In The Shadow of the Alabama: The British Foreign Office and the American Civil War (Naval Institute Press, 2015).

- Merli, Frank J., and David M. Fahey. The Alabama, British Neutrality, and the American Civil War (2004).

- Meyers, Philip E. Caution & Cooperation: The American Civil War in British-American Relations. (2008); A revisionist approach; denies there was much risk of war between the United States and Britain

- Poast, Paul. "Lincoln’s Gamble: Bargaining Failure, British Recognition, and the Start of the American Civil War." (2011) online

- Salisbury, Allen, The Civil War and the American System: America's battle with Britain, 1860–1876 (1978) online

- Sebrell II, Thomas E. Persuading John Bull: Union and Confederate Propaganda in Britain, 1860–1865 (Lexington Books, 2014).

- Sexton, Jay. "Transatlantic financiers and the Civil War." American Nineteenth Century History 2#3 (2001): 29–46.

- Vanauken, Sheldon. The Glittering Illusion: English Sympathy for the Southern Confederacy (Gateway Books, 1989) online

France and Mexico

[edit]- Blackburn, George M. "Paris Newspapers and the American Civil War," Illinois Historical Journal (1991) 84#3 pp 177–193. online

- Blumenthal, Henry. A Reappraisal of Franco-American Relations, 1830–1871 (1959)

- Clapp, Margaret A. (1947). Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow. Winner of the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Biography. Bigelow was the American consul in Paris.

- Carroll, Daniel B. Henri Mercier and the American Civil War (1971); The French minister to Washington, 1860–63.

- Case, Lynn M. and Warren F. Spencer. The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy. 1970).

- Case, Lynn Marshall. French Opinion on War and Diplomacy during the Second Empire (1954).

- Hanna, Alfred J., and Kathryn Abbey Hanna. Napoleon III and Mexico: American Triumph over Monarchy (1971).

- Sainlaude, Stève. Le gouvernement impérial et la guerre de Sécession (2011)

- Sainlaude, Stève. La France et la Confédération sudiste. La question de la reconnaissance diplomatique durant la guerre de Sécession (2011)

- Sainlaude,Stève. France and the American Civil War. A Diplomatic History (2019)

- Schoonover, Thomas. "Mexican Cotton and the American Civil War." The Americas 30.04 (1974): 429–447.

- Sears, Louis Martin. "A Confederate Diplomat at the Court of Napoleon III," American Historical Review (1921) 26#2 pp. 255–281 in JSTOR on Slidell