Democracy in Marxism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

In Marxist theory, a new democratic society will arise through the organised actions of an international working class, enfranchising the entire population and freeing up humans to act without being bound by the labour market.[1][2] There would be little, if any, need for a state, the goal of which was to enforce the alienation of labor;[1] as such, the state would eventually wither away as its conditions of existence disappear.[3][4][5] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels stated in The Communist Manifesto and later works that "the first step in the revolution by the working class, is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class, to win the battle of democracy" and universal suffrage, being "one of the first and most important tasks of the militant proletariat".[6][7][8] As Marx wrote in his Critique of the Gotha Program, "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".[9] He allowed for the possibility of peaceful transition in some countries with strong democratic institutional structures (such as Britain, the US and the Netherlands), but suggested that in other countries in which workers can not "attain their goal by peaceful means" the "lever of our revolution must be force", stating that the working people had the right to revolt if they were denied political expression.[10][11] In response to the question "What will be the course of this revolution?" in Principles of Communism, Friedrich Engels wrote:

Above all, it will establish a democratic constitution, and through this, the direct or indirect dominance of the proletariat.

While Marxists propose replacing the bourgeois state with a proletarian semi-state through revolution (dictatorship of the proletariat), which would eventually wither away, anarchists warn that the state must be abolished along with capitalism. Nonetheless, the desired end results, a stateless, communal society, are the same.[12]

Karl Marx criticized liberalism as not democratic enough and found the unequal social situation of the workers during the Industrial Revolution undermined the democratic agency of citizens.[13] Marxists differ in their positions towards democracy.[14][15]

controversy over Marx's legacy today turns largely on its ambiguous relation to democracy

— Robert Meister[16]

Some argue democratic decision-making consistent with Marxism should include voting on how surplus labor is to be organized.[17]

Soviet Union and Bolshevism

[edit]In the 19th century, The Communist Manifesto (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called for the international political unification of the European working classes in order to achieve a Communist revolution; and proposed that, because the socio-economic organization of communism was of a higher form than that of capitalism, a workers' revolution would first occur in the economically advanced, industrialized countries. Marxist social democracy was strongest in Germany throughout the 19th century, and the Social Democratic Party of Germany inspired Lenin and other Russian Marxists.[18]

During the revolutionary ferment of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and 1917, there arose working-class grassroots attempts of direct democracy with Soviets (Russian for "council"). According to Lenin and other theorists of the Soviet Union, the soviets represent the democratic will of the working class and are thus the embodiment of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Lenin and the Bolsheviks saw the soviet as the basic organizing unit of society in a communist system and supported this form of democracy. Thus, the results of the long-awaited Constituent Assembly election in 1917, which Lenin's Bolshevik Party lost to the Socialist Revolutionary Party, were nullified when the Constituent Assembly was disbanded in January 1918.[19]

Russian historian Vadim Rogovin attributed the establishment of the one-party system to the conditions which were “imposed on Bolshevism by hostile political forces”. Rogovin highlighted the fact that the Bolsheviks made strenuous efforts to preserve the Soviet parties such as the Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, and other left parties within the bounds of Soviet legality and their participation in the Soviets on the condition of abandoning armed struggle against the Bolsheviks.[20] Similarly, British historian E.H. Carr drew attention to the fact “the larger section of the party (the SR party - V.R) had made a coalition with the Bolsheviks, and formally broke from the other section which maintained its bitter feud against the Bolsheviks”.[21]

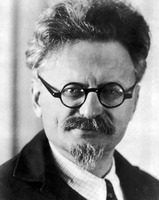

Functionally, the Leninist vanguard party was to provide the working class with the political consciousness (education and organisation) and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism in Imperial Russia.[22] After the October Revolution of 1917, Leninism was the dominant version of Marxism in Russia, and, in establishing soviet democracy, the Bolshevik régime suppressed socialists who opposed the revolution, such as the Mensheviks and factions of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.[23] Trotsky argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved.[24]

In November 1917, Lenin issued the Decree on Workers' Control, which called on the workers of each enterprise to establish an elected committee to monitor their enterprise's management.[25] In December, Sovnarkom established a Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh), which had authority over industry, banking, agriculture, and trade.[26]

Adopting a left libertarian perspective, both the Left Communists and some factions in the Communist Party critiqued the decline of democratic institutions in Russia.[27] Internationally, some socialists decried Lenin's regime and denied that he was establishing socialism; in particular, they highlighted the lack of widespread political participation, popular consultation, and industrial democracy.[28]

Following Stalin's consolidation of power in the Soviet Union and static centralization of political power, Trotsky condemned the Soviet government's policies for lacking widespread democratic participation on the part of the population and for suppressing workers' self-management and democratic participation in the management of the economy. Because these authoritarian political measures were inconsistent with the organizational precepts of socialism, Trotsky characterized the Soviet Union as a deformed workers' state that would not be able to effectively transition to socialism. Ostensibly socialist states where democracy is lacking, yet the economy is largely in the hands of the state, are termed by orthodox Trotskyist theories as degenerated or deformed workers' states and not socialist states.[31] Trotsky and Trotskyists have associated democracy in this context with multi-party socialist representation, autonomous union organizations, internal party democracy and the mass participation of the working masses.[32][33]

The Communist Party of China perspective

[edit]Mao Zedong put forward the concept of New Democracy in his early 1940 text On New Democracy,[34]: 36 written while the Yan'an Soviet was developing and expanding during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[35]: 60–61 During this period, Mao was concerned about bureaucratization and sought to develop a culture of mass politics.[35]: 61 In his view, mass democracy was crucial, but could be guaranteed only to the revolutionary classes.[35]: 61–62 In the concept of New Democracy, the working class and the communist party are the dominant part of a coalition which includes progressive intellectuals and bourgeois patriotic democrats.[36] Led by a communist party, a New Democracy allows for limited development of national capitalism as part of the effort to replace foreign imperialism and domestic feudalism.[36]

The Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) was the primary government body through which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sought to incorporate non-CCP elements into the political system pursuant to principles of New Democracy.[37]: 43 On September 29, 1949, the CPPCC unanimously adopted the Common Program as the basic political program for the country following the success of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[38]: 25 The Common Program defined China as a new democratic country which would practice a people's democratic dictatorship led by the proletariat and based on an alliance of workers and peasants which would unite all of China's democratic classes (defined as those opposing imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalism and favoring an independent China).[38]: 25

From 2007 to 2009, Hu Jintao promoted intra-party party democracy (dangnei minzhu, 党内民主) in an effort to decrease the party's focus on top-down decision-making.[39]: 18

The core socialist values campaign introduced during the 18th National Congress in 2012[40] promotes democracy as one of its four national values.[41]: 204 The Xi Jinping administration promotes a view of consultative democracy (xieshang minzhu 协商民主) rather than intra-party democracy.[39]: 18 This view of socialist democracy emphasizes consulting more often with society at large while strengthening the leading role of the party.[39]: 18

Beginning in 2019, the party developed the concept of "whole-process democracy" which by 2021 was named whole-process people's democracy (the addition of "people's" emphasized a connection to the Maoist concept of the mass line).[42] Under this view, a "real and effective socialist democracy" can be presented as a series of four paired relationships: 1) “process democracy” (过程民主) and “achievement democracy” (成果民主), 2) “procedural democracy” (程序民主) and “substantive democracy” (实质民主), 3) “direct democracy” (直接民主) and “indirect democracy” (间接民主), and 4) “people’s democracy” (人民民主) and the “will of the state” (国家意志).[43] Whole-process people's democracy is a primarily consequentialist view, in which the most important criterion for evaluating the success of democracy is whether democracy can "solve the people's real problems," while a system in which "the people are awakened only for voting" is not truly democratic.[42] As a result, whole-process people's democracy critiques liberal democracy for its excessive focus on procedure.[42]

See also

[edit]- Council democracy

- Council communism

- Criticisms of communist regimes

- Criticisms of Marxism

- List of political parties in the Soviet Union

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Calhoun 2002, p. 23

- ^ Barry Stewart Clark (1998). Political economy: a comparative approach. ABC-CLIO. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-275-96370-5. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "IX. Barbarism and Civilization". Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Zhao, Jianmin; Dickson, Bruce J. (2001). Remaking the Chinese State: Strategies, Society, and Security. Taylor & Francis. p. 2. ISBN 978-0415255837. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas (2011). "Withering Away of the State". The Encyclopedia of Political Science. Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 1776. doi:10.4135/9781608712434.n1646. ISBN 9781933116440. S2CID 221178956.

- ^ Fischer, Ernst; Marek, Franz (1996). How to Read Karl Marx. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-85345-973-6.

- ^ [The Class Struggles In France Introduction by Frederick Engels https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/class-struggles-france/intro.htm]

- ^ Marx, Engels and the vote (June 1983)

- ^ "Karl Marx:Critique of the Gotha Programme".

- ^ Mary Gabriel (October 29, 2011). "Who was Karl Marx?". CNN.

- ^ "You know that the institutions, mores, and traditions of various countries must be taken into consideration, and we do not deny that there are countries – such as America, England, and if I were more familiar with your institutions, I would perhaps also add Holland – where the workers can attain their goal by peaceful means. This being the case, we must also recognise the fact that in most countries on the Continent the lever of our revolution must be force; it is force to which we must some day appeal to erect the rule of labour." La Liberté Speech delivered by Karl Marx on 8 September 1872, in Amsterdam

- ^ Hal Draper (1970). "The Death of the State in Marx and Engels". Socialist Register.

- ^ Niemi, William L. (2011). "Karl Marx's sociological theory of democracy: Civil society and political rights". The Social Science Journal. 48: 39–51. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2010.07.002.

- ^ Miliband, Ralph. Marxism and politics. Aakar Books, 2011.

- ^ Springborg, Patricia (1984). "Karl Marx on Democracy, Participation, Voting, and Equality". Political Theory. 12 (4): 537–556. doi:10.1177/0090591784012004005. ISSN 0090-5917. JSTOR 191498.

- ^ Meister, Robert. "Political Identity: Thinking Through Marx." (1991).

- ^ Wolff, Richard (2000). "Marxism and democracy". Rethinking Marxism. 12 (1): 112–122. doi:10.1080/08935690009358994. ISSN 0893-5696.

- ^ Lih, Lars (2005). Lenin Rediscovered: What is to be Done? in Context. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-13120-0.

- ^ Tony Cliff (1978). "The Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly". Marxists.org.

- ^ Rogovin, Vadim Zakharovich (2021). Was There an Alternative? Trotskyism: a Look Back Through the Years. Mehring Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-893638-97-6.

- ^ Carr, Edward Hallett (1977). The Bolshevik revolution 1917 - 1923. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). Penguin books. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-14-020749-1.

- ^ The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought Third Edition (1999) pp. 476–477.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. (1994), p. 1,558.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (5 January 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ Pipes 1990, p. 709; Service 2000, p. 321.

- ^ Rigby 1979, p. 50; Pipes 1990, p. 689; Sandle 1999, p. 64; Service 2000, p. 321; Read 2005, p. 231.

- ^ Sandle 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Service 2000, pp. 354–355.

- ^ Rogovin, Vadim Zakharovich (2021). Was There an Alternative? Trotskyism: a Look Back Through the Years. Mehring Books. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-1-893638-97-6.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1991). The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and where is it Going?. Mehring Books. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-929087-48-1.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1935). "The Workers' State, Thermidor and Bonapartism". New International. 2 (4): 116–122. "Trotsky argues that the Soviet Union was, at that time, a "deformed workers' state" or degenerated workers' state, and not a socialist republic or state, because the "bureaucracy wrested the power from the hands of mass organizations," thereby necessitating only political revolution rather than a completely new social revolution, for workers' political control (i.e. state democracy) to be reclaimed. He argued that it remained, at base, a workers' state because the capitalists and landlords had been expropriated". Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Mandel, Ernest (5 May 2020). Trotsky as Alternative. Verso Books. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-1-78960-701-7.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1977). The Transitional Program for Socialist Revolution: Including The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International. Pathfinder Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-87348-524-1.

- ^ Liu, Zongyuan Zoe (2023). Sovereign Funds: How the Communist Party of China Finances its Global Ambitions. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674271913.

- ^ a b c Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World: a Concise History. Asia-Pacific series. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4.

- ^ a b Lin, Chun (2006). The Transformation of Chinese Socialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. OCLC 63178961.

- ^ Hammond, Ken (2023). China's Revolution and the Quest for a Socialist Future. New York, NY: 1804 Books. ISBN 9781736850084.

- ^ a b Zheng, Qian (2020). Zheng, Qian (ed.). An Ideological History of the Communist Party of China. Vol. 2. Translated by Sun, Li; Bryant, Shelly. Montreal, Quebec: Royal Collins Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4878-0391-9.

- ^ a b c Cabestan, Jean-Pierre (2024). "Organisation and (Lack of) Democracy in the Chinese Communist Party: A Critical Reading of the Successive Iterations of the Party Constitution". In Doyon, Jérôme; Froissart, Chloé (eds.). The Chinese Communist Party: a 100-Year Trajectory. Canberra: ANU Press. ISBN 9781760466244.

- ^ "How Much Should We Read Into China's New "Core Socialist Values"?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Santos, Gonçalo (2021). Chinese Village Life Today: Building Families in an Age of Transition. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74738-5.

- ^ a b c Pieke, Frank N; Hofman, Bert, eds. (2022). CPC Futures The New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. pp. 60–64. doi:10.56159/eai.52060. ISBN 978-981-18-5206-0. OCLC 1354535847.

- ^ "Whole-Process Democracy". China Media Project. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

Works cited

[edit]- Calhoun, Craig J. (2002). Classical Sociological Theory. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21348-2.

- Fischer, Louis (1964). The Life of Lenin. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Pipes, Richard (1990). The Russian Revolution: 1899–1919. London: Collins Harvill. ISBN 978-0-679-73660-8.

- Read, Christopher (2005). Lenin: A Revolutionary Life. Routledge Historical Biographies. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20649-5.

- Rigby, T. H. (1979). Lenin's Government: Sovnarkom 1917–1922. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22281-5.

- Ryan, James (2012). Lenin's Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-81568-1.

- Sandle, Mark (1999). A Short History of Soviet Socialism. London: UCL Press. doi:10.4324/9780203500279. ISBN 978-1-85728-355-6.

- Service, Robert (2000). Lenin: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-72625-9.

- Volkogonov, Dmitri (1994). Lenin: Life and Legacy. Translated by Shukman, Harold. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-255123-6.

- White, James D. (2001). Lenin: The Practice and Theory of Revolution. European History in Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-72157-5.