Daredevil (Marvel Comics series)

| Daredevil | |

|---|---|

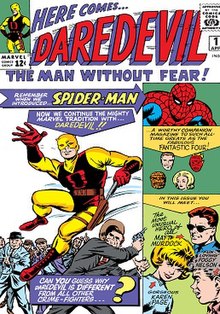

The cover of the first issue of Daredevil (April 1964) features the superhero's debut. Art by Bill Everett. | |

| Publication information | |

| Schedule | Varied |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | Superhero |

| Publication date | 1964 – present |

| No. of issues | List

|

| Creative team | |

| Written by | List

|

| Penciller(s) | List

|

| Inker(s) | List

|

| Colorist(s) | List

|

Daredevil is the name of several comic book titles featuring the character Daredevil and published by Marvel Comics, beginning with the original Daredevil comic book series which debuted in 1964. In the 1960s, the series was written by Stan Lee and first drawn by Bill Everett with some assistance from Jack Kirby, and later by Wally Wood and John Romita Sr.. In the 1970s, it was written by Gerry Conway and Roger McKenzie, among others. Frank Miller's influential tenure on the title in the early 1980s cemented the character as a popular and influential part of the Marvel Universe. He introduced influences from film noir and ninja films, and created the character Elektra. Ann Nocenti, his successor, focused more on themes from left-wing politics. In the 1990s, D.G. Chichester changed the title character's costume. Later in the decade, Joe Quesada restored the series' popularity under the Marvel Knights imprint. Popular film director Kevin Smith also wrote a pivotal arc in the series. Subsequently, Brian Michael Bendis and Alex Maleev collaborated on a critically acclaimed arc.

Publication history

[edit]1960s

[edit]The series began with Marvel Comics' Daredevil #1 (cover date April 1964),[1], written by Stan Lee and drawn by Bill Everett.[2] The cover of the first issue was based on Jack Kirby's original concept sketch, but inked by Everett. Everett penciled the contents of the issue.[3] When Everett turned in his first-issue pencils extremely late, Marvel production manager Sol Brodsky and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko inked a large variety of different backgrounds, a "lot of backgrounds and secondary figures on the fly and cobbled the cover and the splash page together from Kirby's original concept drawing".[4] The first issue covered both the character's origins and his desire to enact justice on the man who had killed his father, boxer "Battling Jack" Murdock, who raised young Matthew Murdock in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Jack instills in Matt the importance of education and nonviolence with the aim of seeing his son become a better man than himself. In the course of saving a blind man from the path of an oncoming truck, Matt is blinded by a radioactive substance that falls from the vehicle. The radioactive exposure heightens his remaining senses beyond normal human limits, and gives him a kind of "radar" sense, enabling him to detect the shape and location of objects around him.[5] To support his son, Jack Murdock returns to boxing under the Fixer, a known gangster, and the only man willing to contract the aging boxer. When he refuses to throw a fight because his son is in the audience, he is killed by one of the Fixer's men. Having promised his father not to use violence to deal with his problems, Matt adopts a new identity who can use physical force. Adorned in a yellow and black costume made from his father's boxing robes and using his superhuman abilities, Matt confronts the killers as the superhero Daredevil, unintentionally causing the Fixer to have a fatal heart attack.[6]

Wally Wood introduced Daredevil's modern red costume in issue #7, which depicts Daredevil's battle against the far more powerful Sub-Mariner, and has become a classic story of the early series.[7] Wood also redesigned Daredevil's costume to include communications equipment; in his depiction, the mask contains a complex radio receiver, and his horns are both antennae to pick up radio signals and amplifiers of his own super-sensory radar blips. However, these concepts would be dropped.[8]

Issue #12 began a brief run by Jack Kirby (layouts) and John Romita Sr. The issue marked Romita's return to superhero penciling after a decade of working exclusively as a romance-comic artist for DC. Romita had felt he no longer wanted to pencil, in favor of being solely an inker. He recalled in 1999,

I had inked an Avengers job for Stan, and I told him I just wanted to ink. I felt like I was burned out as a penciller after eight years of romance work. I didn't want to pencil any more; in fact, I couldn't work at home any more – I couldn't discipline myself to do it. He said, 'Okay,' but the first chance he had he shows me this Daredevil story somebody had started and he didn't like it, and he wanted somebody else to do it.[9]

Romita later elaborated:

Stan showed me Dick Ayers' splash page for a Daredevil. He asked me, "What would you do with this page?" I showed him on a tracing paper what I would do, and then he asked me to do a drawing of Daredevil the way I would do it. I did a big drawing of Daredevil ... just a big, tracing-paper drawing of Daredevil swinging. And Stan loved it.[10]

When Romita left to take over The Amazing Spider-Man,[11] Lee gave Daredevil to what would be the character's first signature artist, Gene Colan, who began with issue #20 (September 1966).[12] Though #20 identifies Colan as a fill-in penciller, Romita's work load prevented him from returning to the title,[13] and Colan ended up penciling all but three issues through #100 (June 1973), plus the 1967 annual, followed by ten issues sprinkled from 1974 to 1979. He would return again for an eight-issue run in 1997.[12]

Lee never gave Colan a full script for an issue of Daredevil; instead, he would tell him the plot, and Colan would tape record the conversation to refer to while drawing the issue, leaving Lee to add the script in afterwards.[14] Though Colan is consistently credited as penciler only, Lee would typically give him the freedom to fill in details of the plot as he saw fit. Lee explained "If I would tell Gene who the villain was and what the problem was, how the problem should be resolved and where it would take place, Gene could fill in all the details. Which made it very interesting for me to write because when I got the artwork back and had to put in the copy, I was seeing things that I'd not expected."[15] The 31-issue Lee/Colan run on the series included Daredevil #47, in which Murdock defends a blind Vietnam veteran against a frameup; Lee has cited it as the story he is most proud of out of his entire career.[16][17] With issue #51, Lee turned the writing chores over to Roy Thomas (who succeeded him on a number of Marvel's titles), but would remain on board as editor for another 40 issues. Daredevil embarks on a series of adventures involving such villains as the Owl and the Purple Man.[18] In issue #16 (May 1966), Daredevil meets Spider-Man, who will eventually become one of Daredevil's closest friends.[19] A letter from Spider-Man unintentionally exposes Daredevil's secret identity, compelling him to adopt a third identity as his twin brother Mike Murdock, whose carefree, wisecracking personality more closely resembles the Daredevil guise than the stern, studious, and emotionally-withdrawn Matt Murdock.[20] The "Mike Murdock" plotline was used to highlight the character's quasi-multiple personality disorder. This third identity was dropped in issues #41–42; Daredevil fakes Mike Murdock's death and claims he had trained a replacement Daredevil.[21] The series' 31-issue run by writer-editor Stan Lee and penciller Gene Colan (beginning with issue #20) includes Daredevil #47, in which Murdock defends a blind Vietnam veteran against a frameup; Lee has cited it as one of his favorite stories.[22][23]

Matt discloses his secret identity to his girlfriend Karen Page in a story published in 1969. However, the revelation proves too much for her, and she breaks off the relationship.[24] This was the first of several long-term breakups between Matt and Karen, who remains a recurring character up until her death in the late 1990s.[25]

1970s

[edit]18-year-old Gerry Conway took over as writer with issue #72, and turned the series in a pulp science fiction direction. Conway also moved Daredevil to San Francisco beginning with Daredevil #86, and simultaneously brought on the Black Widow as a co-star for the series.[26]

Conway explained,

I’d just spent some time in San Francisco a month or two before, and I’d fallen in love with the city as a location. I thought the idea of Daredevil, who spent so much time leaping and diving from rooftop to rooftop, doing this in such a hilly city could make for spectacular visuals. I’ll admit the idea of a blind hero jumping around the rooftops that gave Jimmy Stewart vertigo appealed to me as well. Also, it would allow him to be the costumed hero for an entire city, which would allow him to flourish without having to defer to more superpowered heroes like Spider-Man or the Fantastic Four.[27]

Concerning the Black Widow, he said, "I was a fan of Natasha [Romanoff, the Black Widow], and thought she and Daredevil would have interesting chemistry."[27]

The Black Widow served as Daredevil's crime-fighting ally as well as his lover from November 1971 to August 1975. Issues #92-107 were published under the title Daredevil and the Black Widow. Due to the Comics Code Authority's restrictions on the depiction of cohabitation, the stories made explicit that though Daredevil and the Black Widow were living in the same apartment, they were sleeping on separate floors, and that Natasha's guardian Ivan Petrovich was always close at hand.[27] Conway introduced Black Widow as a romantic partner for Daredevil as "a way to re-energize the title".[28] She joined the series in Daredevil #81 (1971).[29] The series had been suffering from slowly declining popularity, and in November 1971 Marvel announced that Daredevil and Iron Man would be combined into a single series, but the addition of the Black Widow revitalized interest in the comic.[27] John Romita Sr. designed a new costume for Black Widow based on the 1940s Miss Fury comic strip, but Colan was the artist for the series. Conway responded to feminist criticism by making Black Widow a more active and independent character, beginning in Daredevil #91 (1972).[30] The series was retitled Daredevil and the Black Widow in the following issue;[31] her name was dropped from the title after issue #107 (1973).[31] Steve Gerber became the writer for Daredevil with issue #97 (1972). Sales had declined, and in response he re-emphasized Daredevil as the central character.[32] Gerber initially scripted over Conway's plots, but Gene Colan's long stint as Daredevil's penciler had come to an end. Gerber recollected, "Gene and I did a few issues together, but Gene was basically trying to move on at that point. He'd just started the Dracula book, and he'd been doing Daredevil for God knows how many years. I think he wanted to do something else."[33] After six issues with fill-in pencilers, including several with Don Heck, Bob Brown took over as penciller.Tony Isabella became the writer for Daredevil with issue #118, and he believed that Daredevil and Black Widow should be split up.[32] Black Widow departed from the series in issue #124, feeling overshadowed by Daredevil.[31]

Tony Isabella succeeded Gerber as writer, but editor Len Wein disapproved of his take on the series and sent him off after only five issues, planning to write it himself.[34] Instead, he ended up handing both writing and editing jobs to his friend Marv Wolfman with issue #124, which introduced inker Klaus Janson to the title. It also wrote the Black Widow out of the series and returned Daredevil to Hell's Kitchen; the post-Conway writers had all felt that Daredevil worked better as a solo hero, and had been working to gradually remove the Widow from the series.[27] Wolfman's 20-issue run included the introduction of one of Daredevil's most popular villains, Bullseye.[35] He was dissatisfied with his work and quit, later explaining, "I felt DD needed something more than I was giving him. I was never very happy with my DD—I never found the thing that made him mine the way Frank Miller did a year or two later. So I was trying to find things to do that interested me and therefore, I hoped, the readers. Ultimately, I couldn't find anything that made DD unique to me and asked off the title."[36] His departure coincided with Brown's death from leukemia.

Wolfman returned Daredevil to Hell's Kitchen.[27] Wolfman promptly introduced the lively but emotionally fragile Heather Glenn to replace the Black Widow as Daredevil's love interest.[37] Wolfman's 20-issue run included the introduction of one of Daredevil's most popular villains, Bullseye.[38]

With issue #144, Jim Shooter became the writer and was joined by a series of short-term pencilers, including Gil Kane, who had been penciling most of Daredevil's covers since #80 but had never before worked on the comic's interior. The series's once-solid sales began dropping during this period, and was downgraded to bi-monthly status with issue #147. Shooter still had difficulty keeping up with the schedule, and the writing chores were shortly turned over to Roger McKenzie.[39]

McKenzie's work on Daredevil reflected his background in horror comics, and the stories and even the character himself took on a much darker tone.[40] Daredevil battles a personification of death, and a re-envisioning of his Daredevil's origin shows him using stalker tactics to drive the Fixer to his fatal heart attack.[41] McKenzie created chain-smoking Daily Bugle reporter Ben Urich, who deduces Daredevil's secret identity over the course of issues #153–163.[42] Halfway through his run, McKenzie was joined by penciler Frank Miller,[43] who had previously drawn Daredevil in The Spectacular Spider-Man #27 (February 1979),[44] with issue #158 (May 1979).[45]

In a story arc overlapping Wolfman, Shooter, and McKenzie's runs on the series, Daredevil reveals his identity to Glenn. Their relationship persists, but proves increasingly harmful to both of them.[46] Though the Black Widow returns for a dozen issues (#155–166) and attempts to rekindle her romance with Daredevil, he ultimately rejects her in favor of Glenn.[31]

1980s

[edit]

Sales had been declining since the end of the Wolfman/Brown run, and by the time Miller became Daredevil's penciler, the series was in danger of cancellation. Moreover, Miller disliked Roger McKenzie's scripts, and Jim Shooter (who had since become Marvel's editor-in-chief) had to talk him out of quitting.[39] Seeking to appease Miller,[39] and impressed by a short backup feature he had written, new editor Denny O'Neil fired McKenzie so that Miller could write the series.[47] The last issue of McKenzie's run plugs a two-part story which was pulled from publication, as its mature content encountered resistance from the Comics Code Authority, though part one eventually saw print in Daredevil #183, by which time Code standards had relaxed.[48]

Miller continued the title in a similar vein to McKenzie. Resuming the drastic metamorphosis the previous writer had begun, Miller took the step of essentially ignoring all of Daredevil's continuity prior to his run on the series; on the occasions where older villains and supporting cast were used, their characterizations and history with Daredevil were reworked or overwritten.[49] Spider-Man villain Kingpin was introduced as Daredevil's new nemesis, displacing most of his large rogues gallery. Daredevil himself was gradually developed into an antihero. Comics historian Les Daniels noted that "Almost immediately, [Miller] began to attract attention with his terse tales of urban crime."[50] Miller's revamping of the title was controversial among fans, but it clicked with new readers, and sales began soaring,[39] the comic returning to monthly status just three issues after Miller came on as writer.

Miller introduced previously unseen characters who had played a major part in his youth, such as Elektra, an ex-girlfriend turned lethal ninja assassin.[51] Elektra was killed fighting Bullseye in issue #181 (April 1982), an issue which saw brisk sales.[52]

With #185, inker Janson began doing the pencils over Miller's layouts, and after #191 Miller left the series entirely. O'Neil switched from editor to writer. O'Neil was not enthusiastic about the switch, later saying "I took the gig mostly because there didn't seem to be (m)any other viable candidates for it."[47] He continued McKenzie and Miller's noir take on the series, but backed away from the antihero depiction of the character. Janson left shortly after Miller, replaced initially by penciler William Johnson and inker Danny Bulanadi, who were both supplanted by David Mazzucchelli. Miller returned as the title's regular writer, co-writing #226 with O'Neil. Miller and Mazzucchelli crafted the acclaimed "Daredevil: Born Again" storyline in #227–233.[53] Miller intended to produce an additional two-part story with artist Walt Simonson but the story was never completed and remains unpublished.[54]

Three fill-in issues followed before Steve Englehart (under the pseudonym "John Harkness")[55][56] took the post of writer, only to lose it after one issue due to a plot conflict with one of the fill-ins. Ann Nocenti was brought on as a fill-in writer but became the series's longest-running regular writer, with a four-and-a-quarter-year run from #238 to #291 (January 1987 – April 1991). The shuffle of short-term artists continued for her first year, until John Romita Jr. joined as penciller from #250 to #282 (January 1988 – July 1990) alongside inker Al Williamson, who stayed on through #300.

The team returned Murdock to law by co-founding with Page a nonprofit drug and legal clinic, while Nocenti crafted stories confronting feminism, drug abuse, nuclear proliferation, and animal rights-inspired terrorism.

1990s

[edit]New writer D. G. Chichester and penciler Lee Weeks continued from where Nocenti left off. The critically acclaimed "Last Rites" arc from #297–300 saw Daredevil regaining his attorney's license and finally bringing the Kingpin to justice.[57]

The creative team of Chichester and penciler Scott McDaniel changed the status quo with their "Fall From Grace" storyline in issues #319–325 (August 1993 – February 1994).[58] Elektra, who was resurrected in #190 but had not been seen since, finally returned.

Under writers Karl Kesel and later Joe Kelly, the title gained a lighter tone, with Daredevil returning to the lighthearted, wisecracking hero depicted by earlier writers. Gene Colan returned to the series during this time, but though initially enthusiastic about drawing Daredevil again, he quit after seven issues, complaining that Kesel and Kelly's scripts were too "retro".[59]

In 1998, Daredevil's numbering was rebooted, with the title "canceled" with issue #380 and revived a month later as part of the Marvel Knights imprint.[60] Joe Quesada drew the new series, written by filmmaker Kevin Smith.[61] Its first story arc, "Guardian Devil", depicts Daredevil struggling to protect a child whom he is told could either be the Messiah or the Anti-Christ.

Smith was succeeded by writer-artist David Mack, who contributed the seven-issue "Parts of a Hole" (vol. 2 #9–15).

2000s

[edit]David Mack brought independent-comics colleague Brian Michael Bendis to Marvel to co-write the following arc, "Wake Up" in vol. 2 #16–19 (May 2001 – August 2001).[62] Following Mack and Bendis were Back to the Future screenwriter Bob Gale and artists Phil Winslade and David Ross for the story "Playing to the Camera". Mack continued to contribute covers, while Brian Michael Bendis wrote further stories such as Daredevil: Ninja.

Issue #26 (December 2001) brought back Brian Michael Bendis, working this time with artist Alex Maleev. IGN called Bendis's four-year-run "one of the greatest creative tenures in Marvel history" and commented that it rivaled Frank Miller's work.[63]

Writer Ed Brubaker and artist Michael Lark became the new creative team with Daredevil vol. 2 #82 (February 2006),[64] no longer under the Marvel Knights imprint.

The series returned to its original numbering with issue #500 (October 2009),[65] which followed vol. 2 #119 (August 2009). New writer Andy Diggle revised the status quo,[66][67] with Daredevil assuming leadership of the ninja army the Hand.

2010s

[edit]Following this came the crossover story arc "Shadowland".[68] Murdock then leaves New York, leaving his territory in the hands of the Black Panther in the briefly retitled series' Black Panther: Man Without Fear #513–523.

In July 2011, Daredevil relaunched with vol. 3 #1 (September 2011),[69] with writer Mark Waid and penciler Paolo Rivera. Waid said he was interested in "tweaking the adventure-to-depression ratio a bit and letting Matt win again".[70] Daredevil vol. 3 ended at issue #36 in February 2014.[71]

Daredevil vol. 4 launched under Waid and Chris Samnee with a new issue #1 (March 2014) as part of the All-New Marvel NOW! storyline.[72][73] Daredevil vol. 4 officially ended with issue #18 in September 2015.

Daredevil vol. 5 began as part of the All-New, All-Different Marvel branding, written by Charles Soule with art by Ron Garney with the first two issues released in December 2015.[74] Charles Soule released his final Daredevil storyline "Death of Daredevil" during the October and November 2018 releases, in a 4-part bimonthly release which ended the series.[75]

2020s

[edit]Afterwards the series went on hiatus for two months and resumed distribution in February 2019, with a brand-new volume written by Chip Zdarsky. The primary artist on the series is Marco Checchetto.[75] In August 2021, it was confirmed that vol. 6 of the series would end in November 2021, at issue #36.[76] The series lead into the crossover event Devil's Reign with the same creative team.[77] Following the conclusion of that series, Daredevil vol. 7, also written by Zdarsky, was launched in July 2022.[78] In March 2023, it was announced Zdarsky's time on Daredevil would end in August 2023.[79] In May 2023, it was announced that Saladin Ahmed would serve as the writer of Daredevil vol. 8 and that Aaron Kuder serving as illustrator. The first issue is set to debut in September 2023.[80]

Reception

[edit]Empire praised Frank Miller's era, and referenced Brian Michael Bendis, Jeph Loeb, and Kevin Smith's tenures on the series, describing the character as a "compelling, layered and visually striking character".[81] IGN ranked Daredevil as the third best series from Marvel Comics in 2006[82]

Comic Book Resources ranked Daredevil as the 13th-best Marvel superhero, but said it had the best overall comic runs because "writers have been able to craft their vision as intended, which isn't always possible with more well-known titles".[83][84]

The series has also won the following awards:

- Daredevil #227: "Apocalypse", Best Single Issue – 1986 Kirby Awards

- Daredevil: Born Again, Best Writer/Artist (single or team), Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli – 1987 Kirby Awards

- Daredevil: The Man Without Fear, Favorite Limited Comic-Book Series – 1993 Comics Buyer's Guide Fan Award[85]

- Daredevil by writer Brian Michael Bendis and artist Alex Maleev, 2003 Eisner Awards (for works published in 2002)[86]

- Daredevil, Best Writer, Ed Brubaker – 2007 Harvey Award

- Daredevil #7, Best Single Issue (or One-Shot) – 2012 Eisner Awards (for works published in 2011)[87]

- Daredevil by Mark Waid, Marcos Martín, Paolo Rivera, and Joe Rivera, Best Continuing Series – 2012 Eisner Awards

- David Mazzucchelli's Daredevil Born Again: Artist's Edition, edited by Scott Dunbier (IDW), Best Archival Collection – 2013 Eisner Awards

- Chris Samnee, Daredevil v3, Best Penciller/Inker – 2013 Eisner Awards

Collected editions

[edit]Daredevil's comic series has been collected into many trade paperbacks, hardcovers and omnibuses.

References

[edit]- ^ Murray 2013, p. 7.

- ^ De Falco 2022, p. 94.

- ^ Murray 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Quesada, Joe (May 2005). "Joe Fridays 4 (column)". Newsarama. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ^ Hanefalk 2022, p. 185.

- ^ Murray 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Murray 2013, p. 8-9.

- ^ Murray 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Interview: "John Romita Sr.: Spidey's Man". Comic Book Artist (6). TwoMorrows Publishing. Fall 1999. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010.

- ^ John Romita Sr., interviewed by former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas: "Fifty Years on the 'A' List". Alter Ego. 3 (9). July 2001. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. (2012). "1960s". In Gilbert, Laura (ed.). Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 35. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Artist John Romita, the penciler that would define the looks of Spider-Man and Peter Parker for an entire generation, had his first crack at drawing the web-slinger in a two-part story of the Stan Lee penned series Daredevil.

- ^ a b Wolk, Douglas (July 2, 2007). Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work, and What They Mean. Da Capo Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-306-81509-6.

- ^ Field, Tom (2005). Secrets in the Shadows: The Art & Life of Gene Colan. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1893905450.

- ^ Field, p. 58

- ^ Field, p. 61

- ^ McLaughlin, Jeff (2007). Stan Lee: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. p. 185. ISBN 978-1578069859.

There was a Daredevil story about a blind guy that I loved [issue #47].

- ^ The Very Best of Marvel Comics [trade paperback]. Marvel Comics. 1991. p. 157.

- ^ Duarte 2013, p. 13-20.

- ^ Callahan 2013, p. 25.

- ^ Callahan 2013, p. 21-31.

- ^ Callahan 2013, p. 31.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007, p. 185. "There was a Daredevil story about a blind guy that I loved [issue #47]."

- ^ Lee, Stan (1991). "Brother, Take My Hand!". The Very Best of Marvel Comics. Marvel Comics. p. 157. ISBN 0-87135-809-3.

- ^ Lindsay 2013a, p. 102-104.

- ^ Lindsay 2013a, p. 104-108.

- ^ Sanderson 2022, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f Carson, Lex (December 2010). "Daredevil and the Black Widow: A Swinging Couple of Crimefighters". Back Issue! (45). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 31–38.

- ^ Harvey 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Frankel 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Frankel 2017, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Frankel 2017, p. 63.

- ^ a b Harvey 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Field, p. 115

- ^ Mithra, Kuljit (May 1997). "Interview With Tony Isabella". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Sanderson, Peter "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 175: In March [1976], writer Marv Wolfman and artist Bob Brown co-created one of the Man Without Fear's greatest nemeses, Bullseye.

- ^ Mithra, Kuljit (November 1997). "Interview With Marv Wolfman". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Young 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Sanderson 2022, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d Mithra, Kuljit (July 1998). "Interview With Jim Shooter". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Young 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Young 2016, p. 55-56.

- ^ Young 2016, p. 70-71.

- ^ Sanderson 2022, p. 179.

- ^ Saffel, Steve (2007). "Weaving a Broader Web". Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Titan Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4.

Frank Miller was the guest penciler for The Spectacular Spider-Man #27, February 1979, written by Bill Mantlo. [The issue's] splash page was the first time Miller's [rendition of] Daredevil appeared in a Marvel story.

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 189: In this issue the great longtime Daredevil artist Gene Colan was succeeded by a new penciller who would become a star himself: Frank Miller.

- ^ Young 2016, p. 34.

- ^ a b Mithra, Kuljit (February 1998). "Interview With Dennis O'Neil". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Comtois, Pierre (December 2014). Marvel Comics in the 80s: An Issue by Issue Field Guide to a Pop Culture Phenomenon. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-1605490595.

- ^ Miller, Frank (w), Miller, Frank (p), Austin, Terry (i). "Roulette" Daredevil, no. 191 (May 1980). Marvel Comics.

- ^ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. Harry N. Abrams. p. 188. ISBN 9780810938212.

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 201: "Matt Murdock's college sweetheart first appeared in this issue [#168] by writer/artist Frank Miller."

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 207: "Frank Miller did the unthinkable when he killed off the popular Elektra in Daredevil #181...[This issue] immediately sold out in comic book stores and sent fans and retailers to raid mass market newsstands for all the remaining copies."

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 226: "'Born Again' was a seven-issue story arc that appeared in Daredevil from issue #227 to #233 (February – August 1986)."

- ^ Mithra, Kuljit (August 1997). "Interview With Walt Simonson". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

The gist of it is that by the time Marvel was interested in having us work on the story, Frank was off doing Dark Knight and I was off doing X-Factor. So it never happened. Too bad—it was a cool story too.

- ^ Englehart, Steve (n.d.). "Daredevil". SteveEnglehart.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

[S]ince all the plotlines I set up went to waste I put my "John Harkness" pseudonym on it.

- ^ Mithra, Kuljit S. (June 1997). "Interview With Steve Englehart". ManWithoutFear.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 258: "Culminating in the anniversary 300th issue, Daredevil would finally gain the upper hand against longtime foe Wilson Fisk (the Kingpin) in this moody tale by writer D. G. Chichester and penciller Lee Weeks."

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 263

- ^ Field, p. 149

- ^ Daredevil vol. 2 at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 290: "It was a dream come true for many comic fans. Kevin Smith, the writer/director of such cult films as Clerks, Mallrats, and Chasing Amy...had been hired by Marvel to write Daredevil, a character whose title many thought could use a major facelift."

- ^ Manning "2000s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 305: "Writer Brian Michael Bendis began his impressive run on the Daredevil title with a small character-driven four-part story, teaming with his old friend David Mack."

- ^ George, Rich (September 16, 2005). "Daredevil: The Bendis Trades – Frank Miller has met his equal". IGN. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ Manning "2000s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 331: "Writer Ed Brubaker and artist Michael Lark had quite a challenge ahead of them when they took over the reins of Daredevil from the popular team of writer Brian Michael Bendis and artist Alex Maleev."

- ^ Daredevil (continuation of vol. 1) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Phegley, Kiel (March 26, 2009). "Diggle on Daredevil". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ^ Brady, Matt (March 24, 2009). "Moving into Hell's Kitchen: Andy Diggle Talks Daredevil". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ^ Richards, Dave (April 17, 2010). "C2E2: Diggle Leads Daredevil into Shadowland". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ Daredevil vol. 3 at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Ash, Roger (April 27, 2011). "Interview: Mark Waid on Marvel's Daredevil". Westfield Comics Blog. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Sunu, Steve (October 23, 2013). "Daredevil To Conclude With Issue #36". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (November 25, 2013). "Mark Waid Returns to Daredevil in March 2014". IGN. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014.

Marvel announced that Waid and artist Chris Samnee will be returning to helm the fourth volume of Daredevil.

- ^ Casey, Dan (November 25, 2013). "Exclusive: Mark Waid and Chris Samnee Talk Daredevil #1 for All-New Marvel NOW!". Nerdist.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Secret Wars Ends, A-Force, Totally Awesome Hulk & More Debut in Marvel's December 2015 Solicitations". Comic Book Resources. September 15, 2015. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Newsarama | GamesRadar+". gamesradar. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ Marston, George (2021-08-16). "Marvel is ending Zdarsky and Checchetto's Daredevil ... for now". gamesradar. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "The Kingpin Declares War in 'Devil's Reign'". Marvel Entertainment. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "Chip Zdarsky And Marco Checchetto Reunite For An All New Era Of Daredevil". Marvel Entertainment. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ Zdarsky, Chip (10 March 2023). "Just A Nice Friday Update". zdarsky.substack.com. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ "The New Era of Daredevil Starts in Saladin Ahmed and Aaron Kuder's 'Daredevil' #1". Marvel Entertainment. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Comic Book Characters". Empire. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (August 11, 2006). "The Ten Best Marvel Comics". IGN. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Allan, Scoot; Harth, David (7 September 2024). "25 Most Popular Marvel Characters, Ranked". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Donohoo, Timothy Blake (12 September 2024). "10 Best Marvel Heroes With The Greatest Comic Runs". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 13 September 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "1993 Comic Buyer's Guide Fan Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ "2000s Eisner Award Recipients". San Diego Comic-Con. 2 December 2012. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ "2010s Eisner Award Recipients". San Diego Comic-Con. 2 December 2012. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2022). Marvel Year by Year: A Visual History. New Edition. DK. ISBN 978-0-7440-5451-4.

- DeFalco, Tom. "1960s". In Gilbert, pp. 70-135.

- Sanderson, Peter. "1970s". In Gilbert, pp. 136-183.

- Hanefalk, Christine (2022). Being Matt Murdock: One Fan's Journey Into the Science of Daredevil. Tomp Press. ISBN 978-91-987965-0-6.

- Lindsay, Ryan K., ed. (2013). The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil. Sequart Organization. ISBN 978-0-5780-7373-6.

- Murray, Will. "A Different Daredevil". In Lindsay (2013), pp. 3-12.

- Lindsay, Ryan K. (2013a). "Blind Dates and Broken Hearts: The Tragic Loves of Matthew Murdock". In Lindsay (2013), pp. 98–147.

- Comics publications

- 1964 comics debuts

- Comics by Brian Michael Bendis

- Comics by Dennis O'Neil

- Comics by Ed Brubaker

- Comics by Frank Miller (comics)

- Comics by Gerry Conway

- Comics by J. M. DeMatteis

- Comics by Kevin Smith

- Comics by Marc Guggenheim

- Comics by Mark Waid

- Comics by Marv Wolfman

- Comics by Roy Thomas

- Comics by Stan Lee

- Comics by Steve Gerber

- Comics set in New York City

- Crime comics

- Daredevil (Marvel Comics)

- Literature about blind people

- Marvel Comics adapted into films

- Marvel Comics titles