Cumberland sauce

Lamb roulades with Cumberland sauce | |

| Type | Savoury sauce |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Britain |

| Serving temperature | Cold |

| Main ingredients |

|

Cumberland sauce is a savoury sauce of English origin, made with redcurrant jelly, mustard, pepper and salt, blanched orange peel, and port wine. The food writer Elizabeth David described it as "the best of all sauces for cold meat".[1] It is thought to be of 19th-century origin. Among the conjectural reasons for its name are honouring a Duke of Cumberland or alternatively reflecting the county of its origin.

History and contents

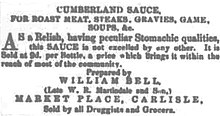

[edit]Piquant spicy fruit sauces rendered sharply sour with verjuice or vinegar featured prominently in medieval cuisine.[2] Cumberland sauce, thought to have originated in the 19th century, is in that tradition. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it as "a piquant sauce served esp. with cold meat".[3] The dictionary's earliest citation for a sauce of that name is 1878, but it is mentioned in The Times six years earlier, reporting a banquet in Berlin in September 1872, attended by the Emperors Wilhelm I, Franz Joseph and Alexander II, at which hure de sanglier (boar's head) was served with "sauce Cumberland".[4] In 2009 a food historian, Janet Clarkson, identified an American citation from 1856, as well as details of some sauces from earlier in the 19th century that bore similarities to what became known as Cumberland sauce:[5] she instanced William Kitchiner's, The Cook's Oracle, first published in 1817, which includes an unnamed "Wine sauce for Venison or Hare" in which claret or port are mixed with redcurrant jelly.[6]

Elizabeth David found a recipe from 1853 by Alexis Soyer for what she says "is without doubt Cumberland sauce":[1]

Cut the rind, free from pith, of two Seville oranges into very thin strips half an inch (1cm) in length, which blanch in boiling water, drain them upon a sieve and put them into a basin, with a spoonful of mixed English mustard, four of currant jelly, a little pepper, salt (mix well together) and half a pint (300ml) of good port wine.[1]

Soyer described his recipe as "the German method of making a sauce to be eaten with boar's head",[7] and David followed up the German connection with mention of the popular belief that the sauce was named for the Hanoverian prince Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.[1] She added that a simple connection with the county of Cumberland (now part of Cumbria) was also a possibility. Two Cumberland newspapers of the 1850s repeatedly carried advertisements for a bottled Cumberland sauce, although no hint was given of the ingredients.[8] After commenting that the supposed Hanoverian origin was "as good as any and better than some", David added that it was odd that Cumberland sauce is not mentioned in any 19th-century cookery book, including those by Eliza Acton, Mrs Beeton and Charles Elmé Francatelli. The first printed recipe for a specifically named Cumberland sauce identified by David was in a French book about English food, published in 1904. She found further French associations: Henry Babinski described a similar sauce in his Gastronomie pratique (1907),[1] and Auguste Escoffier popularised it and printed his recipe in the "Sauces anglaises froides" section of his Ma cuisine (1934), particularly commending the sauce as an accompaniment to cold venison.[9]

In David's view it is "the best of all sauces for cold meat – ham, pressed beef, tongue, venison, boar's head or pork brawn".[1] More recently Michel Roux, Sr. wrote of Cumberland sauce that it was his favourite sauce for terrines, pâtés and game. "We often serve it at The Waterside Inn and I never tire of it. It adds an entirely new dimension to a pork pie bought from the delicatessen".[10]

A Polish variant omits mustard and wine, adds horseradish, and fries the orange zest before adding it to the mixture.[11] A New Zealand version adds grated beetroot.[12] Recipes for more or less the generic version on Soyer's lines appear in cookery books from, among other countries, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Sweden and the US.[13]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f David, pp. 70–72

- ^ Peterson, p. 11

- ^ "Cumberland sauce". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "The Imperial Festivities", The Times, 10 September 1872, p. 4

- ^ Clarkson, Janet. "Cumberland Sauce", Old Foodie, 15 September 2009

- ^ Kitchiner, p. 299

- ^ Soyer, p. 413

- ^ See, e.g. front-page advertisements in the Carlisle Journal and the Carlisle Patriot, 23 December 1859, and 24 December 1859

- ^ Escoffier, p. 43

- ^ Roux, p. 73

- ^ Pininska, p. 120

- ^ Parsons, p. 90

- ^ Pawlowská, p. 230; Escoffier, p. 43; Swann, p. 22; Johnson, p. 201; Bardají, p. 120; Bauer, p. 143; and Stamm, p. 39

Sources

[edit]- Bardají, Teodoro (1993). Índice culinario. Zaragoza: Val de Onsera. ISBN 978-84-88518-05-7.

- Bauer, Mange (2012). I'll take the same – Mat på mitt vis. Norderstedt: Books on Demand. ISBN 978-91-7463-045-9.

- David, Elizabeth (2000) [1970]. Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-902304-66-3.

- Escoffier, Auguste (1965) [1934]. Ma cuisine. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-02450-7.

- Johnson, Margaret (1999). The Irish Heritage Cookbook. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. OCLC 1035753570.

- Kitchiner, William (1827). The Cook's Oracle: Containing Practical Receipts. London: Simpkin & Marshall. OCLC 1040257989.

- Parsons, Pamela (1999). Simply New Zealand: A Culinary Journey. Auckland: New Holland. ISBN 978-1-877246-26-5.

- Pawlowská, Halina (2014). Chuť do života. Prague: Motto. ISBN 978-80-267-0155-2.

- Peterson, James (2017). Sauces: Classical and Contemporary Sauce Making. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-81982-5.

- Pininska, Mary (1991). The Polish Kitchen. London: Papermac. ISBN 978-0-333-56871-2.

- Roux, Michel (1998). Sauces: Sweet and Savoury, Classic and New. London: Quadrille. ISBN 978-1-899988-38-9.

- Soyer, Alexis (1847). The Gastronomic Regenerator. London: Simpkin & Marshall. OCLC 969501531.

- Stamm, Sara (1981). The Park Avenue Cookbook. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-15585-4.

- Swann, Peter (2006). Ofengerichte. Bath: Parragon. ISBN 978-1-4054-6340-9.

External links

[edit]- Recipe at Chef de Cuisine.com Archived 7 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine