Catherine Destivelle

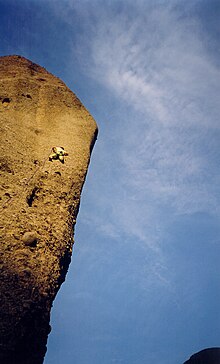

Catherine Destivelle climbing on the Adrachti tower in Greece | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | French | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 24 July 1960 Oran, French Algeria | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | Professional rock climber and mountaineer, and publisher | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (163 cm)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Erik Decamp (m. 1996) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Climbing career | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of climber | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Highest grade | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| First ascents |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Named routes | Voie Destivelle in Petit Dru | ||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Updated on 12 December 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Catherine Destivelle (born 24 July 1960) is a French rock climber and mountaineer who is considered one of the greatest and most important female climbers in the history of the sport. She came to prominence in the mid-1980s for sport climbing by winning the first major female climbing competitions, and by being the first female to redpoint a 7c+/8a sport climbing route with Fleur de Rocaille in 1985,[a] and an 8a+ (5.13c) route with Choucas in 1988. During this period, she was considered the strongest female sport climber in the world along with Lynn Hill, however, in 1990 she retired to focus on alpine climbing.

In 1990, she made the first female alpine ascent of the Bonatti Pillar on the Petit Dru, which she followed up in 1991, by becoming the first female to create a new extreme alpine route, also on the Petit Dru, which was named Voie Destivelle in her honor. From 1992 to 1994, Destivelle became the first female to complete the winter alpine free solo of the "north face trilogy" of the Eiger, the Grandes Jorasses, and the Matterhorn. She made Himalayan and high-altitude ascents such as Nameless Tower in 1990, the southwest face of Shishapangma in 1995, and the south face of Peak 4111, in Antarctica, in 1996.

As well as her Alpine free solos, she made other notable free solos, such as the Devils Tower in 1992, and the Old Man of Hoy in 1997. She is the subject of several documentaries, including Rémy Tezier's, Beyond the Summits, which won the best feature-length film award at the 2009 Banff Film Festival. In 2007, she was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour, and in 2020, became the first female recipient of the Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award.

Early life and education

[edit]Catherine Destivelle was born in Oran, in French Algeria, to French parents, Serge and Annie Destivelle. Catherine was the eldest of six (four sisters Florence, Sophie, Martine, and Claire, and one brother Hyacinthe). Her father was an amateur climber and mountaineer. As a young teenager, her family moved to Paris, France, where she attended the Lycée Corot in Savigny-sur-Orge.[2][3]

At the age of 12, Destivelle became a member of the Club alpin français, and started bouldering in Fontainebleau,[4] multi-pitch big wall climbing in Burgundy, and alpine climbing in the Massif des Écrins.[2] By 1976, aged 16, she was spending her summer in the Verdon Gorge, with climbing-partner, Pierre Richard. In that year, Destiville made alpine ascents of the Cousy-Desmaison Route (ED) on the north face of l'Olan, and the Devies-Gervasutti Route (TD+), on the northwest face of Ailefroide.[4] The following year, in 1977, she ascended the American Direct Route (ED1), on the west face of Le Petit Dru in Chamonix.[4]

From 1980 to 1985, Destivelle focused on studying physiotherapy at the Ecole de kinésithérapie de Paris, and then working full-time as a physiotherapist.[3][4][5]

Climbing career

[edit]Sport climbing and competition climbing

[edit]In 1985, Destivelle became a professional climber, which happened almost by accident after being asked to do a climbing film, E pericoloso sporgersi, that captured her making the first female ascent of the 1,000-metre multi-pitch sport route Pichenibule in Verdon, which was only the second-ever female ascent in history of a 7b (5.12b) route;[2][4] after the film, she was offered sponsorships.[3][6] In 1985, Destivelle made what was thought to be the first female breakthrough into the 8a (5.13b) grade with Fleur de Rocaille, however, its grade was subsequently softened to 7c+/8a.[a][2]

Destivelle initially rejected competition climbing, co-signing the 1985 Manifeste des 19, but then changed her mind and won at Sportroccia in 1985, the first international climbing competition (held in Bardonecchia and Arco), which later became the Rock Master annual competition.[4] Later that year, she fractured her pelvis in a fall in Chamonix.[2][4] Destivelle recovered and in 1986 set new records by becoming the first female to climb an 8a (5.13b) route with Fleur de Rocaille (later downgraded to 7c+/8a), and winning again at Sportroccia, beating her main rival Lynn Hill.[2][5][8]

1988 would be the pinnacle of Destivelle's sport climbing career when she redpointed Choucas in Buoux, the first female ascent of an 8a+ (5.13c) graded route.[4][9] She had repeated several 8a (5.13b) routes that year in preparation, including Rêve de Papillon, Elixir de Violence, Samizdat, and La Diagonale du Fou.[3] She also beat her fellow French rival Isabelle Patissier to win her third Sportroccia title.[2][4] In 1989, Destivelle won the first international climbing competition held in the US, organized by Jeff Lowe at Snowbird, Utah.[2][4][10] In 1990, Destivelle finished third at the annual Snowbird international competition and decided to retire from competition climbing to focus on mountaineering and alpine climbing.[4]

Alpine climbing

[edit]In 1990, Destiville came to international attention[11] with the first female ascent of the Bonatti Pillar (TD+: 5.9 A1) on the southwest face of the Petit Dru, which she completed as a free solo in 4 hours; in 1955 Walter Bonatti spent six days on the route as he made what became regarded as one of the most famous ascents in history.[4][12]

In 1991, Destivelle completed one of her most notable alpine climbing feats by opening up a new route on the west face of the Petit Dru, named the Voie Destivelle (or Destiville Route) (VI 5.11b A5). Her 11-day free solo of the route, which bears her name in her honor, was captured in the film 11 Days on the Dru, and covered widely in the international media.[4][12]

Destivelle turned her attention to completing the free solo climb, in winter, of the three greatest north faces in the Alpes (the winter "North Face Trilogy" of Ivano Ghirardini).[13] She started in 1992, making the first female solo ascent of the 1938 Heckmair Route (ED2) on the north face of the Eiger in 17-hours (and featured in the 1992 climbing film, Eiger).[4][13] In 1993, she made the first female solo ascent of the Walker Spur (ED1, 5.8 A1) on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses.[4][13] In 1994, she completed the 'winter solo trilogy' climbing the Bonatti Route (ED2/3) on the Matterhorn.[4][12][13]

In 1999, she completed the first female free solo of the Brandler-Hasse Route (ED-: 5.10c A0), on the north face direct of the Cima Grande di Lavaredo; her last major alpine climb.[4]

Himalayan and high-altitude climbing

[edit]In 1990, Destivelle went on an expedition with Jeff Lowe and David Breashears to try a new route on Nameless Tower in the Karakoram, however, poor conditions forced them to change plans and they instead made the second free ascent of Yugoslav Route (VI 5.12a) (and featured in the 1990 climbing film, Nameless Tower).[12][14] In 1992, Destivelle went on another expedition with Jeff Lowe to climb the north ridge on the north face of Latok I, in the Karakoram, but was forced back due to severe storms.[15]

In 1993, she went on an expedition to the west face of Makalu with Jeff Lowe and French mountaineering guide, Erik Decamp (who would later become her husband). Lowe tried an alternative solo route while Destivelle and Decamp tried the West Pillar, however, both groups were unsuccessful due to severe snowfall.[16] In 1995, Decamp and herself made a successful ascent of the Loretan-Troillet-Kurtyka Routeon the southwest face of Shishapangma.[17] In 1995, the pair were less successful in attempting to open a new route on the south face of Annapurna, beside the old Bonington Route.[18] In January 1996, after the pair successfully completed a new route on the south face of Peak 4111 in Antarctica, Destivelle fell 20-metres through a cornice while momentarily unroped on the summit, and suffered a severe compound leg fracture. Destivelle thought she would die given their remote position, however, a 15-hour self-rescue brought her to safety.[19]

Free soloing

[edit]Destivelle is known for her free soloing of multi-pitch rock climbs, and both alpine big wall and alpine mixed climbs (i.e. rock climbing and ice climbing).[20][21] On a 1992 tour to the US, she free soloed the second half of El Matador 5.10d (6b+) on the Devils Tower in Wyoming, and Supercrack 5.10b (6a+), in Indian Creek, Utah (both are captured in the 1992 climbing film, Ballade à Devil's Tower), and in 1997, while four months pregnant, free soloed the Old Man of Hoy in Scotland (captured in the 1998 film, Rock Queen).[20]

During 1992–1994, she completed the winter free solo trilogy of the north faces of the Eiger, the Grandes Jorasses and the Matterhorn.[20] In a 2020 interview with Rock & Ice she said: "When I'm free soloing, I feel O.K. I always have a big safety margin, I'm not struggling. You feel quite powerful and calm. If I ever felt afraid, I wouldn't go. I don't like to bet".[20][22] She said of her Eiger free solo: "I didn't want people to say it was the first female ascent, I wanted to be the first person to climb the Eiger onsight and solo in winter".[22]

Legacy

[edit]Destivelle is widely considered one of the greatest all-around female climbers in the history of the sport.[6][5][11][23] In 2014, the former editor of the Alpine Journal, Ed Douglas, called her "the world's most famous woman alpinist during the 1990s".[6] When she became the first female recipient of the Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020, PlanetMountain said: "the 59-year-old Frenchwoman is considered one of the greatest climbers and mountaineers of all times".[13] In 2020, Climbing magazine noted her pioneering role in competition climbing and her rivalry with Lynn Hill as they vied for the title of the strongest female sport climber, but noted that her true passion was for alpinism, and said of her achievements: "Catherine Destivelle crushed the stereotypes that top-level sport climbing and daring alpinism were reserved for men. She is one of the most well-rounded climbers of all time—from the boulders of Fontainebleau to the Himalaya—and her storied career serves as inspiration to climbers everywhere".[11]

Personal life

[edit]In 1996, Destivelle and Erik Decamp were married, and their son, Victor, was born at the end of the following year.[4][24] After the birth of Victor, Destivelle began to cut back on free solo and extreme climbs in the late 1990s and developed a career as a lecturer, speaker and a mountaineering writer. In 1998 she told The Independent: "I can't bear to leave Victor for more than an hour", and "I don't want to climb with anyone except Eric. And we could not leave Victor behind". By 2000, she completely retired from any major sport climbing or alpine climbing activities.[24]

In 2011, in partnership with Bruno Dupety, she became a publisher at her firm, "Les Editions du Mont Blanc", a company specializing in books about mountaineering and alpinism.[25]

Awards

[edit]- In 1993, Knight of the Ordre national du Mérite in France.[26]

- In 2007, Knight of the Legion of Honour in France.[26]

- In 2008, King Albert Mountain Award.[27]

- In 2020, 12th Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award, she became the first female recipient and its youngest-ever recipient.[11][13][9]

Notable climbs

[edit]Sport climbing

[edit]During her competition years, Destivelle was considered one of the world's best sport climbers.[5]

- 1983 – La Dudule 7a (5.11d), Saussois, France, the third-ever female 7a in history.[2]

- 1985 – Pichenibule 7b+ (5.12c), Verdon, France, the second-ever female 7b+ in history (captured in the 1985 climbing film, E Pericoloso Sporgersi').[2]

- 1985 – Fleur de Rocaille 7c+/8a , Mouriès, France, the first female 7c+/8a; this was initially considered the first 8a, but it was later downgraded one notch.[a][2][28]

- 1988 – Rêve de Papillon 8a (5.13b), Buoux, France, the fourth-ever female 8a in history.[3]

- 1988 – Elixir de Violence 8a (5.13b), Buoux, France.[3]

- 1988 – Samizdat 8a (5.13b), Cimaï, France.[3]

- 1988 – La Diagonale du Fou 8a (5.13b), Buoux, France.[3]

- 1988 – Chouca 8a+ (5.13c), Buoux, France, the first female 8a+ in history.[2][7]

Free solo rock climbing

[edit]Destivelle was also one of the few rock climbers who practiced free soloing at extreme grades.[20][5]

- 1985 – El Puro, Mallos de Riglos in Spain

- 1987 – Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali (captured in the 1987 climbing film, Seo).[4][9][29]

- 1989 – Phi Phi Islands in Thailand (captured in the 1989 climbing film, Solo Thai).[4][9]

- 1992 – Supercrack 5.10b (6a+), Indian Creek, Dead Horse Point State Park in Utah (captured in the 1992 climbing film, Ballade à Devil's Tower).[30]

- 1992 – El Matador 5.10d (6b+), Devils Tower in Wyoming (captured in the 1992 climbing film, Ballade à Devil's Tower).[20][31]

- 1997 – Old Man of Hoy sea-stack in Orkney Islands, Scotland (captured in the 1998 film, Rock Queen).[20][32]

Alpine climbing

[edit]Destivelle was the first woman to complete the following solo alpine climbing and big wall climbing ascents:[4][5]

- 1990 (October) – Bonatti Pillar (TD+: 5.9 A1), on the southwest face of the Petit Dru, first female free solo.[12][5]

- 1991 (June) – Voie Destivelle (VI 5.11b A5), west face of the Petit Dru, first free ascent and first female to free an alpine route of that level of technical difficulty;[4][5] also the first major Alps route to be named after a woman (captured in the 1991 climbing film, 11 Days on the Dru).[23][33]

- 1992 (March) – 1938 Heckmair Route (ED2), north face of the Eiger, first female winter free solo (captured in the 1992 climbing film, Eiger).[4][5][34]

- 1993 (February) – Walker Spur (ED1: 5.8 A1), north face of the Grandes Jorasses, first female winter free solo.[4][5][34]

- 1994 (February) – Bonatti Route (ED2/3), north face of the Matterhorn, first female winter free solo; and first female to complete Ivano Ghirardini's winter "North Face Trilogy".[4][5][34]

- 1999 (June) – Brandler-Hasse Route (ED-: 5.10c A0), north face direct of the Cima Grande di Lavaredo, first female free solo of one of the six great north faces of the Alps.[4][5]

Himalayan and high-altitude climbing

[edit]She also went on innovative and challenging Himalayan and high-altitude mountaineering projects.[5]

- 1990 (September) – Yugoslav Route (VI 5.12a), Trango (Nameless) Tower, Karakoram, second free ascent with Jeff Lowe and David Breashears (captured in the 1990 climbing film, Nameless Tower).[4][14]

- 1992 (August) – North Ridge, north face of Latok I, Karakoram, unsuccessful attempt with Jeff Lowe that retreated at 5,800-meters due to storms.[4][15]

- 1993 (May) – West Pillar, west face of Makalu, Nepal, expedition with Jeff Lowe (who tried a different route); Destivelle and Erik Decamp reached 7,600-metres before retreating due to heavy snow.[4][16]

- 1994 – Losar (VI, ice grade WI5), Namche Bazaar, Nepal, first ascent of the 700-metre frozen waterfall with Erik Decamp (captured in the 1997 climbing film, La Cascade).[4][35][23]

- 1995 (September) – Loretan-Troillet-Kurtyka Route, southwest face of Shishapangma, China, summitted with Erik Decamp.[4][17]

- 1995 (October) – South Face of Annapurna, Nepal, Destivelle and Erik Decamp reached 7,800-metres on a new route (right of the Bonington Route), before retreating due to heavy snow.[4][18]

- 1996 (January) – South Face (TD: V 5.10), of Peak 4111, Ellsworth Mountains, Antarctica, first ascent with Erik Decamp; suffers compound leg fracture after a 20-metre fall on summit cornice.[4][19]

Bibliography

[edit]Destivelle is the author of the following books:

- Danseuse de roc, Denoël, 1987 (ISBN 978-2207233948)

- Rocs nature (with photos by Gérard Kosicki), Denoël, 1991 (ISBN 978-2207238981)

- Annapurna: Duo pour un 8000 (with Érik Decamp), Arthaud, 1994 (ISBN 2-7003-1059-4)

- L'apprenti alpiniste: L'escalade, l'alpinisme et la montagne expliqués aux enfants (with Érik Decamp and Gianni Bersezio), Hachette Jeunesse, 1996 (ISBN 978-2012916623)

- Ascensions, Arthaud, 2003 (ISBN 2-7003-9594-8)

- Le petit alpiniste: La montagne, l'escalade et l'alpinisme expliqués aux enfants (with Érik Decamp and Claire Robert), Guérin, 2009 (ISBN 978-2352210382)

- Rock Queen, Hayloft Publishing Ltd, 2015 (ISBN 978-1910237076)

- L'escalade, tu connais?, Editions du Mont Blanc, 2017 (ISBN 978-2-36545-026-3)

- L'alpinisme, tu connais?, Editions du Mont Blanc, 2019 (ISBN 978-2-36545-046-1)

Filmography

[edit]Destivelle has been the subject of several films and documentaries:[36]

- E Pericoloso Sporgersi, Robert Nicod, 1985

- Seo, Pierre-Antoine Hiroz, 1987

- Solo Thai, Laurent Chevallier, 1989

- Nameless Tower, David Breashears, 1990

- 11 Jours dans les Drus, Gilles Sourice, 1991

- Eiger, Stéphane Deplus, 1992

- Ballade à Devils's Tower, Pierre-Antoine Hiroz, 1992

- La Cascade, Pierre-Antoine Hiroz, 1997

- Rock Queen, Martin Belderson, 1998

- Au-delà des cimes (Beyond the Summits), Rémy Tézier, 2008; winner of the best feature-length film award at the 2009 Banff Mountain Film Festival.[37]

See also

[edit]- List of grade milestones in rock climbing

- History of rock climbing

- Josune Bereziartu, greatest female sport climber of the 1990s and 2000s

- Wolfgang Güllich, greatest sport climber of the 1980s

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Roberts, David (June 2012). "A Mountain of Trouble". Men's Journal. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

On February 11th, Catherine Destivelle arrived from Chamonix. Five feet four inches tall, with curly brown hair, a conquering smile and a formidable physique, she is a superstar in France, yet fame has left her relatively unaffected.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Virilli, Mathias (11 August 2020). "Part 1: Catherine Destivelle, a golden career: rock star of the 80s". Montagne. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Destivelle, Catherine (2003). Ascensions. Arthaud. ISBN 2-7003-9594-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Faces: Catherine Destivelle". Alpinist. 7. June 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2022..

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Stefanello, Vinicio (24 July 2017). "Catherine Destivelle, climbing and alpinism there where it is dangerous to lean out". PlanetMountain. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Ed (11 March 2014). "Jury trial: Catherine Destivelle at the Piolets d'Or". Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b Oviglia, Maurizio (23 December 2012). "The evolution of free climbing". PlanetMountain.com. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Roberty, Dave (2 May 2004). "And the Best Woman Sport Climber is…". Outside. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

In the early days of competition climbing the two who usually vied for first place were Hill and Catherine Destivelle, a Frenchwoman who has since turned her attention to her original passion, mountaineering.

- ^ a b c d Editorial (28 July 2020). "Catherine Destivelle Honored With Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award". Rock & Ice. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Catherine Destivelle to Receive Piolets d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award". Gripped. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Slavsky, Bennett (23 July 2020). "Catherine Destivelle Earns Piolets d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award". Climbing. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Virilli, Mathias (12 August 2020). "Part 2: Catherine Destivelle, a golden career: solo mountaineering". Montagne. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Gardien, Claude (23 July 2020). "Catherine Destivelle awarded Piolet d'Or Carrière Lifetime Achievement Award". PlanetMountain. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Breashers, David (1991). "Asia, Pakistan, Nameless Tower, Trango Towers". American Alpine Journal. 33 (65). American Alpine Club: 270–272. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hawley, Elizabeth (1993). "Asia, Pakistan, Latok Attempt". American Alpine Journal. 35 (37). American Alpine Club: 205, 268. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hawley, Elizabeth (1994). "Asia, Nepal, Makalu West Face Attempts". American Alpine Journal. 36 (68). American Alpine Club: 205. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Decamps, Erik (1995). "Asia, Tibet, Shisha Pangma, Southwest Face Attempt". American Alpine Journal. 67 (37). American Alpine Club: 205, 307. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Decamps, Erik (1995). "ASIA, NEPAL, ANNAPURNA, SOUTH FACE ATTEMPT". American Alpine Journal. 67 (37). American Alpine Club: 254. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Decamps, Erik (1997). "Misadventures Below Zero, Up Against It in Antarctica". American Alpine Journal. 39 (71). American Alpine Club: 98–102. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Osius, Alison (4 June 2022). "Free Solo Rock Climbing and the Climbers Who Have Defined the Sport". Climbing. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Dave (2 May 2004). "Mountaineering: Queen of Solo, Catherine Destivelle". Outside. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b Levy, Michael (17 March 2020). "Catherine Destivelle: What I've Learned". Rock & Ice. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "Five Women Who Deserve the Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award". Gripped Magazine. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b Arthur, Charles (24 May 1998). "Mother of all climbdowns". The Independent. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Qui sommes nous ? - les éditions du Mont-Blanc - Livres sur la Montagne et l'Alpinisme". Archived from the original on 2014-04-06. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ a b Virilli, Mathias (14 August 2020). "Part4 4: Catherine Destivelle, a golden career: the passion to transmit". Montagnes. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Catherine Destivelle". King Albert Awards. 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Mouries". Grimper. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Geldard, Jack (August 2009). "Catherine Destivelle Climbing Solo in Mali". UKClimbing. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Catherine Destivelle Free Solos Supercrack (5.10b), Indian Creek". Rock & Ice. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Watch Catherine Destivelle Free-Solo Devils Tower". Gripped. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

One of the most rad free-solos caught on film in the 1990s

- ^ "Watch Catherine Destivelle Free-Solo Old Man of Hoy". Gripped. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

Catherine Destivelle was one of the first, bold soloists of the modern-era of climbing. Watch her free-solo Old Many of Hoy in Scotland in 1998, she was also four months pregnant, after rope-soloing the lower pitches

- ^ Slung, Michele B., Living with Cannibals and Other Women's Adventures, National Geographic Society, 2000, p. 56

- ^ a b c Destivelle, Caterine (2020). "Eiger (1992)". American Alpine Journal. 62 (94). American Alpine Club: 58. Retrieved 2025-01-12.

- ^ McDonald, Dougald (11 March 2008). "Weihenmayer Does 14-Pitch Nepali Ice Climb". Climbing. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography, "Destivelle, Catherine", Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003, p. 429. ISBN 0-618-25210-X

- ^ CBC News, Finding Farley wins at Banff Mountain Film Festival, November 9, 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2010

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Catherine Destivelle, Director of Editions du Mont-Blanc, her publishing company.

- VIDEO: Catherine Destivelle Free Soloing Devils Tower, Wyoming, Rock & Ice (February 2018)

- VIDEO: Catherine Destivelle Free Soloing Supercrack, Indian Creek, Rock & Ice (April 2016)

- VIDEO: Catherine Destivelle Free Soloing Old May of Hoy, Scotland, Gripped Magazine (January 2019)

- Interview: What I've Learned, Rock & Ice (17 March 2020)

- 1960 births

- Living people

- People from Oran

- 21st-century French women

- French female climbers

- Free soloists

- Ice climbers

- French rock climbers

- French mountain climbers

- French female mountain climbers

- French female ski mountaineers

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour

- Piolet d'Or winners

- Recipients of the Albert Mountain Award

- French competition climbers

- People of French Algeria

- Pieds-noirs

- 20th-century French sportswomen