Cady Noland

Cady Noland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1956 (age 67–68) Washington, D.C., US |

| Education | Sarah Lawrence College |

| Known for | |

| Notable work |

|

Cady Noland (born 1956) is an American sculptor, printmaker, and installation artist who primarily works with found objects and appropriated images. Her work, often made with objects denoting danger, industry, and American patriotism, addresses notions of the failed promise of the American Dream, the divide between fame and anonymity, and violence in American society, among other themes. Art critic Peter Schjeldahl called Noland "a dark poet of the national unconscious."[1]

She is also known for her numerous disputes and lawsuits with museums, galleries, and collectors over their handling of her work, as well as for her reluctance to be publicly identified, having only ever allowed two photographs of herself to be publicly released.

Noland has participated in several high profile exhibitions, including the 44th Venice Biennale (1990), Whitney Biennial (1991), and Documenta 9 (1992). After widely exhibiting her art in the 1980s and 1990s to broad acclaim, Noland largely stopped presenting her work for nearly two decades. She began exhibiting again in the late 2010s, staging a museum retrospective in 2018 and exhibitions of new work in the early 2020s.

A major museum survey of Noland's work, her first in the United States, is currently on view at Glenstone in Potomac, Maryland, until February 23, 2025.

Early life and education

[edit]Cady Noland was born in 1956 in Washington, D.C., the daughter of Kenneth Noland and Cornelia Langer.[2]

Kenneth was a well-known color field painter and Langer, also an artist, co-owned a clothing and accessories store in Alexandria, Virginia, though the two divorced in 1957.[3] After the divorce, Kenneth moved to New York to live in the Chelsea Hotel before buying a property in Shaftsbury, Vermont; Langer eventually remarried to Dr. Donald J. Reis in 1985.[3] Art critic Robert Hughes wrote before his death that Kenneth had been an active member of the Sullivanian psychotherapy cult run by Saul B. Newton, which encouraged participants to discard their familial relations;[4] Langer was later photographed for an article in The New York Times about a custody trial related to the cult and was identified with two other women as "relatives of Sullivanian collective members."[5]

Noland grew up in New York,[6] sometimes spending time at her father's property in Vermont.[3] She attended Sarah Lawrence College, Langer's alma mater, and moved to Manhattan after graduation.[7] While in college she studied under sociology professor Stephen N. Butler, whom she would later cite as an influence on her work.[8]

Speaking as an adult about her hometown of Washington, Noland said it was "a city of façade," adding, "What's behind it? We're two-faced! I'm trying to break the façade – mix things up."[9] She has also said that growing up around her father's practice as an artist helped her to understand the machinations of the art world from an early age: "Dealers were already demystified for me."[10]

Life and career

[edit]1980s: Career beginnings

[edit]Following her move to New York, Noland began making artworks with found objects in 1983.[11] Among her earliest works was Total Institution (1984), a multimedia assemblage sculpture created with a phone receiver, toilet seat, rubber chicken, and other objects hanging from a rack on a wall.[6] In 1987 Noland created a slide lecture titled "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil" which she presented at the International Conference on the Expressions of Evil in Literature and the Visual Arts, an academic conference in Atlanta. The lecture explored Noland's research into psychopathology, with a focus on the social violence of what she called the "successful" American man.[12]

In 1988 Noland attended an open house for artists at the nonprofit gallery White Columns where she showed Polaroid images of her art to the director of the gallery, Bill Arning.[2] Arning later said the images confused him, as the installations in the pictures did not seem like traditional artworks, but rather collections of objects: "I couldn’t tell where the art was. She was doing these installation pieces. And I was fascinated."[2] After visiting Noland's studio, Arning invited her to present her first solo exhibition in a gallery at White Columns.[2] Noland spent so long finalizing the works in the gallery that Arning gave her the keys to lock up when he went home for the night.[7][2]

Noland's exhibition at White Columns, White Room: Cady Noland, opened in March 1988.[13] Works in the exhibition were made with medical equipment like IV bags and walkers and industrial materials like rubber mats and jumper cables,[2] along with a silk screen depiction of a pistol.[7] She also installed a metal bar across the door, forcing visitors to duck to enter.[7] Journalist Julia Halperin has described the exhibition as "a cross between a Social Security office, a police station and a hospital."[7] When Arning first saw Noland's installation after returning to the gallery, he said "I had this sense that something significant had happened, art historically."[7] He has said he immediately called patrons of the gallery to tell them "Look, something really important happened here, and I think you need to see it.”[2] Noland's exhibition received broad critical acclaim in art publications and she was soon invited to participate in several high-profile exhibitions in the United States and internationally.[7] In November 1988,[14] Noland staged her first solo exhibition outside the United States,[15] at Galerie Westersingel 8 in Rotterdam, which featured mixed media mirrored constructions.[16] Noland's exhibition was part of a series of shows by New York-based artists staged in conjunction with Rotterdam's 1988 cultural festival.[14]

Noland exhibited solo at Colin de Land's American Fine Arts Co. gallery in April 1989, presenting multiple works focusing on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.[17] She silk screened historical images of Lincoln's boots, the suit he was wearing when he was shot, and the bloody cot he died on,[18] along with snippets of text from a minute-by-minute news report of the assassination, onto metal panels that she leaned against the wall.[19] She also exhibited several found object installations, including Our American Cousin, a pen-like metal enclosure in the center of the gallery filled with empty beer cans, stacked walkers, handcuffs, a barbecue grill, license plates, and hamburger buns.[20] The work was titled after the play Lincoln had been viewing the night he was assassinated.[21][17] Other installations she showed at the exhibition included Celebrity Trash Spill, a work displayed on the floor featuring a copy of the New York Post with the headline "Abbie Hoffman Dead,"[20] and The American Trip, an assemblage sculpture featuring an American flag paired with a variant of the Jolly Roger.[22] Additionally, Noland used metal bars installed around the space to block access to certain areas, including bars situated around the gallery reception desk, bars blocking the entry to the gallery owner's office, and bars surrounding the owner's desk.[19][23] Reviewing the exhibition for Arts Magazine, critic Gretchen Faust called Our American Cousin the "centerpiece" of the show, adding that the piece "capture[s] the flavor, really the essence, of a Chevy truck commercial."[20] Multiple critics identified chromed or shiny metal as a central visual motif in Noland's work in their reviews of the exhibition.[24][25][26]

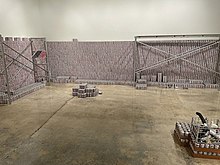

In October 1989, Noland staged a solo exhibition at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, where she installed This Piece Has No Title Yet.[2] One of Noland's best-known works, the piece is a room-sized installation composed of over 1000 six-packs of Budweiser beer stacked behind metal scaffolding with American flags, handcuffs, and other detritus scattered around the room.[2] The museum borrowed the beer from a local distributor and had to dismantle and rebuild the installation three times over the course of the show to return the beer so it could be sold before it expired.[27] Noland said that Budweiser cans "serve as a kind of 'flag manqué'" in her art because of their similarity in color to American flags, and she described the cans as "tiny units of mastery" for their visual representation of mass production, commodification, and consumption.[28] John Caldwell, a curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art, called the work "jaw-dropping" and tried unsuccessfully to convince local collectors in Pittsburgh to buy it,[2] but it was instead purchased by New York-based collector Elaine Dannheisser.[29] Curator and dealer Jeffrey Deitch later called the work Noland's "masterpiece, her greatest work."[29]

Noland then mounted a solo show at Galleria Massimo De Carlo in Milan, in December 1989, where she almost completely filled the gallery with objects strewn across the floor and installed on the walls[30] - including beer cans, walkers, bungee cords, metal clips, a flipper and snorkel, a revolver, flags, potato chips, and a gas mask.[31] The largest work in the show, Deep Social Space,[30] consisted of beer cans, an American flag, saddles and horse blankets, a barbecue grill, a rural USPS mailbox, a crutch, dish towels and an apron, hamburger buns, and containers of motor oil and Quaker oats, among other objects, all stacked and arranged among and between two parallel sets of metal bars and barriers.[30][32] She also installed a large number of silk screened works, many of which comprised metal panels with media images and reports from the life and travails of kidnapping victim and heiress Patty Hearst, including pictures of Hearst in a cheerleading uniform, Hearst on a hunting trip with her boyfriend, and Hearst wielding a gun with members of the Symbionese Liberation Army.[30] Noland also debuted Oozewald, a silk screened metal cut-out work featuring an image of Lee Harvey Oswald - John F. Kennedy's assassin - being assassinated himself; Noland cut several circular holes in the cut-out, including one over Oswald's mouth, into which she stuffed an American flag.[30] In addition, Noland again installed metal bars and gates throughout the gallery which forced viewers to follow certain paths and blocked them from entering spaces.[31]

The same year, Noland published an illustrated essay version of "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil" in the fourth volume of the little known Spanish magazine Balcon.[33] The essay was accompanied by illustrations of works by artists including Sherrie Levine, Peter Nagy, Steven Parrino, and Barbara Kruger, along with stock photographs of car crashes and other transportation accidents.[33] She later called the essay a critique of "a model of the entrepreneurial male whose goals excuse any and all sorts of egregious behavior if those goals are met with success.”[34]

Speaking to filmmaker John Waters and art historian Bruce Hainley in 2003, Noland said that an unnamed art dealer had censored her work in the late 1980s.[35] For a group exhibition, Noland installed a metal pole across a doorway with a small American flag that had been cut at an angle hanging from the pole. Noland told Waters and Hainley that the unnamed gallerist had "rushed at me screaming and hyperventilating, 'I took that piece down. The other ones are still there...CAN'T attract the IRS...collectors offended...not THAT, Cady...they are right...right.'"[36] She also relayed a story of the same gallery owner censoring the title of a work by Parrino,[36] and curator Bob Nickas later confirmed that the unnamed dealer was John Gibson.[37]

1990s: International acclaim

[edit]

Noland's work was included in the 44th Venice Biennale in May 1990, in the exhibition's Aperto section.[2] Noland exhibited Deep Social Space,[32] a sprawling found object installation she first debuted in Milan, in 1989.[30] She also installed several silk screened works featuring images of Oswald and Hearst, commercial advertising images of cowboys, and a photograph of a nineteenth-century prostitute's dwelling in the Pacific Northwest.[32] Critic Peter Schjeldahl, reviewing the exhibition for Mirabella, said that the "effect of the ensemble is drastically melancholic; a cumulative charge of forlorn facts that affect a viewer like personal memories of childhood unhappiness."[32] Discussing Noland's work as among the most popular in the exhibition, critic Amei Wallach, writing in Newsday, said collectors were "hot on [her] tracks..."[38]

In July 1990, Noland staged New West-Old West,[39] a solo show at Luhring Augustine Gallery and Galerie Max Hetzler's joint gallery location in Los Angeles.[2] Works in the exhibition included a large wooden log cabin facade, a large staircase leading to a wall, an antique western chuckwagon, cut-out images of cowboys, silk screened metal panels with images of Mary Todd Lincoln and texts about the history of Colt guns, along with found objects on the floor of the gallery including raw lumber, a trash-filled dustpan, empty beer cans, rubber chickens, animal hides, and flags.[39] One room of the exhibition included works Noland created in collaboration with graphic designers, comprising commercial-seeming slogans and imagery for imagined products or companies with tag-lines like "Loans My Ass," displayed along with a barroom door, a bubble-wrapped car bumper, tools, and a cow's skull.[39] In addition, Noland asked the gallery staff to wear stereotypical American frontier outfits like chaps, holsters, and cowboy hats that she rented for the duration of the exhibition, and staff were made to answer the phone by saying "howdy."[39][2] Noland said that the outfits "functioned as a kind of alternative or additional performance laid over the roles already being performed" by the staff in their day-to-day work,[40] adding that "It was a very difficult month for them but they were really good sports."[41] Reviewing the exhibition for the Los Angeles Times, critic Kristine McKenna said Noland's show was "a wild ride through the junked landscape of America," and that it "suggests that our collective mind is like a hamster cage, padded with a thick, comforting layer of trash."[39]

Collectors were only approved to purchase her work from her solo exhibition in Los Angeles if they agreed to sign a contract stipulating that Noland would be involved with any future sale of the work; gallery co-owner Lawrence Luhring later said that Noland was "very cautious" in dealing with the art market.[7] In 1992 Noland developed a similar contract that required any owners of a work to donate 15% of sale profits to a homelessness prevention nonprofit if the work were ever resold, which she used when selling several print works to collectors.[42][43]

In August 1990, Noland participated in curator Ralph Rugoff's group exhibition Just Pathetic at Rosamund Felsen Gallery in Los Angeles,[44] which sought to define the stylistic movement Rugoff had termed "pathetic art."[45] Noland exhibited several assemblage works from the previous five years, including Pedestal (1985), a combination of a rubber mat, belt, and deflated soccer ball arranged to look like a potted plant, along with Chicken in a Basket (1989), a shopping basket filled with a rubber chicken, bungee cord, beer cans, and a crumpled American flag beneath the pile of objects.[46] Critic Christopher Knight, writing in the Los Angeles Times, called the latter work one of the "most affecting pieces" in the exhibition, describing it as "suggesting the morning-after clean-up following a particularly unspeakable party."[44]

In 1991 Noland participated in the Whitney Biennial, installing This Piece Has No Title Yet in a corner on the top floor of the exhibition.[47][29] She also installed several of her silk screen works featuring images of Oswald and Hearst.[48] Noland’s installation in the Biennial was critically divisive, with some hailing her as a star of the exhibition and others panning her work completely. Writing in the Los Angeles Times, Knight said that Noland "pretty much walk[ed] away with the Biennial."[49] Comparing Noland’s work positively to what he labeled a mostly “lackluster” group of works by other young artists on the top floor of the exhibition, critic Michael Kimmelman wrote that her installation “slowly suggests in its odd stackings of cans and placement of objects that a mysterious and compulsive sensibility may be at work.”[47] Similarly, critic Ken Johnson, grouping Noland with Kiki Smith and Jim Shaw as artists whose “genuinely compelling qualities” should not be overlooked amidst the “prevalence of juvenile tendencies on the top floor,” said that she “hits some deep notes” in a "sociological way."[50] Writing in Art Papers, critic Susan Canning said the placement of Noland’s “subversive and messily unfinished installation” in the back corner of the exhibition - as opposed to a more well-trafficked gallery near the entrance - represented “the curator’s lack of commitment to the social and political discourse of contemporary art.”[51] Conversely, critic Thomas McEvilley wrote in Artforum that Noland's installation "might be a candidate for the emperor's new clothes of this biennial."[48] Writing in Women's Art Magazine, critic Louisa Buck said that "while [Noland's] work is a blunt comment on the vacancy of American culture and the banality of art, politics and consumer culture, it seems too loose and arbitrary to have real critical teeth."[52] Critic Arthur Danto called Noland's work an "intolerable and patronizing exercise," writing that her installation and the rest of the works on the top floor of the show exuded a "mood of aggressiveness."[53]

In February 1992, Noland exhibited a site-specific installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), which included several works created for the museum's space that Noland gifted to MOCA.[54] As part of the installation, she used push-pins to attach Xerox copies of blurry images to the gallery walls, placed paint buckets and installation hardware around the room, and put aluminum scaffolding on the floor in a corner hidden behind a length of corrugated sheet metal.[55] She also installed several chain-link fences and steel blockades and works featuring Oswald and Hearst, in addition to leaving scuff marks and drill holes on the walls of the gallery.[55]

Noland was selected to exhibit at Documenta 9 in June 1992 in Kassel.[33] She presented a three-dimensional version of her essay "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil," featuring passages of the text silk screened onto boards placed haphazardly on the ground and leaning against walls in an underground parking garage.[56][33] She added an addendum to the essay for this version titled "The Bonsai Effect" that laid out her criticism of American excess and waste.[33] Noland also installed artworks by artists featured in the illustrated version of the essay,[33] and surrounded the installation with cinder blocks, oil, a Camaro, and a van turned on its side with smashed windows.[56] Denys Zacharopoulos, a co-director of that year's Documenta exhibition, said Noland had been selected for the show because of "the clear position with which the artist transformed a possible group show into a collective single work."[57] Zacharopoulos also described Noland's choice to install her show in a parking garage as "quite shocking at the time," labelling the space "a threatening, empty cavity."[58] Knight, again writing in the Los Angeles Times, called Noland's installation "the show's succes d'estime."[56] Speaking a decade later about her experience participating in Documenta, Noland said that it had been "psychically amazing, but it tests your character to have to account not only for what you do in the studio but for what your work means in the world," adding that "the international spotlight that Documenta shines on artists [...] can be overwhelming."[59]

In 1993 Noland staged a two-artist exhibition with Doug MacWithey at the Dallas Museum of Art.[2] Noland produced several silk screen works printed on reflective metallic surfaces that she called "funhouse mirrors," and she directed the museum to make four wheelchairs available in the galleries for all visitors,[2] which were themselves made with a reflective metal similar to many of Noland's artworks.[33] Noland later said in an interview that "I get impatient and lazy looking at art myself," and added that "The wheelchairs allowed you to move if you wanted to, you were not trapped."[2] Also in 1993 she began producing large silk screen works on aluminum depicting red brick walls.[33]

For a solo exhibition in 1994 at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, her first show in the city since 1989, Noland produced four sculptures which appear like combinations between a pillory and stocks.[60][2] The sculptures were interactive and she allowed viewers to lock themselves in.[60][2][7] Noland has said that she believes stocks, often situated in town squares, were the first form of public sculpture in colonial America.[61] These works were first inspired by a work-in-progress by Parrino titled Stockade: Existential Trap for Speed Freaks; Parrino said that "Cady called me to ask if it was okay to make stockade pieces. I told her she didn’t need my permission."[62] In addition to the stocks sculptures, Noland presented Publyck Sculpture,[7] a set of aluminum-covered wooden beams with three tires hanging down from ropes like a swing set, which was inspired by a similar-looking tire swing found in cult leader Charles Manson's final hiding place.[60] She also produced several silk screen works featuring images and text excerpts from newspapers about celebrities and public figures including: Thomas Eagleton, a former U.S. Senator and Vice Presidential candidate whose career faltered when his hospitalizations for depression were made public; Wilbur Mills, a former U.S. Representative who resigned and entered rehab for alcoholism after several public incidents with Fanne Foxe, an exotic dancer; Vince Foster, a deputy White House Counsel under President Bill Clinton who died by suicide after experiencing work-related depression and anxiety; Martha Mitchell, a whistleblower during the Watergate scandal who was allegedly kidnapped, beaten, and drugged in order to silence her; Peter Holm, the ex-husband of actress Joan Collins; Manson and his cult, the Manson Family; and others involved in scandal, controversy, or public crimes.[60][63] Eagleton's son reportedly brought his father to see the exhibition featuring his image.[7] Critic Roberta Smith described the exhibition as "a walk-in scrapbook of various crimes, misdemeanors and scandals."[60] Writing in Frieze, critic David Bussel observed that the people in the images selected by Noland "have been thwarted, in life or in death, by the repercussions of fame, burnt out ‘victims.’"[64]

Speaking to curator John S. Weber in 1994, Noland said that she was "not particularly interested" in the "particular people or events" depicted in many of her works. Weber wrote that "What intrigues her is their exemplary function as objects of media attention, along with the voracious news-processing system that conjures them into being."[65] She has said she spends hundreds of hours in news archives searching for source material for these works.[66][15]

In June 1996 Noland opened a solo exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.[67] She exhibited several silk screened works on metal leaning against the walls of the gallery,[67] including images of Eagleton, Foster, Holm, Mills, and Mitchell, along with: Squeaky Fromme, a member of the Manson Family who attempted to assassinate President Gerald Ford; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, President Kennedy's widow, pictured with the fashion designer Valentino, whose face had been etched away by Noland; First Lady Betty Ford; and actor Burt Reynolds.[68] She also installed a set of metal bleachers in the gallery for visitors to sit and view the installation, similar to seating for a sporting event.[7] Additionally, she included a tire swing sculpture, My Amusement, and a stocks sculpture titled Sham Rage.[69] Noland was dissatisfied with the installation prior to its opening, and she spent hours with museum staff adjusting the placement of works until the exhibition "snapped into place," according to the curator.[7] Reviewing the show for the Hartford Courant, critic Owen McNally observed that "Noland makes media voyeurs of us all by seating us in her bleachers."[70] Writing in 1996 about the juxtaposition of her stocks sculptures with her silk screened works, curator Philip Monk said that Noland was exploring a lineage of shame and humiliation in American society: "Placed in the context of media images, [the stocks sculptures] collapsed the centuries between Puritan town square and tabloid exposure..."[71]

Noland also produced an editioned work for the magazine Parkett in 1996 as part of the publication's editions program. The work, Not Titled Yet, comprised a piece of cardboard with holes cut similar to her stocks sculptures, covered with a lacquer sander sealant and aluminum enamel spray paint.[3]

In 1999 Noland exhibited in a group show curated by artist Robert Gober at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York, alongside work by Anni Albers, Joan Semmel, Nancy Shaver, and video artist Robert Beck.[72] Noland presented her first new work to be exhibited since 1994,[73] Stand-In for a Stand-In, a variant of her stocks sculptures made out of cardboard and wood and covered in silver paint, sitting on a rubber mat, which Gober placed in the center of the gallery space.[74] She called the piece a "study after the fact" of her earlier stocks sculptures.[75] Several critics wrote that Gober's layout for the installation resembled the division of familial or domestic archetypes, with Noland's work representing violence or discipline.[76][77][78]

Also in 1999, Noland staged a two-artist exhibition with artist and writer Olivier Mosset at the Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zurich.[79] Noland exhibited several new sculptures made with a-frames which she placed as barricades in various parts of the gallery;[79] she made these works by threading a length of plywood painted white through the center of multiple white plastic a-frames, which she was able to move back and forth along the plywood to change the visual composition of the sculptures.[73] The only other new work in the exhibition was a large cardboard tube that Noland covered completely with sheets of adhesive paper bearing black-and-white logos.[73] She also exhibited a number of earlier works borrowed from museums and private collections,[73] including multiple pieces comprising metal poles standing in the center of car tires, a large silk screen work of a brick wall, and Publyck Sculpture.[79] In addition, she used a chain-link fence to cordon off several sections of the gallery, rendering the areas inside inaccessible.[33]

2000s: Retreat from art world

[edit]Following a group exhibition in 2000 with Team Gallery in New York, Noland largely stopped exhibiting new work or engaging publicly with the art world for over a decade.[2][7] The exhibition in 2000 featured a new a-frame barricade sculpture, which Noland installed so it almost completely blocked the entrance to the small gallery space.[80][2] An unnamed art dealer attempted to purchase an edition of the sculpture, but Noland had instructed the gallery not to sell her work to other art dealers; the owner of Team Gallery, José Freire, said of Noland, "This was a person who wanted her work treated in a certain way."[2] By the end of the exhibition, the work hadn't sold, and Noland asked the gallery to get rid of it by placing the a-frames in the street one at a time over several days until they were taken or disappeared.[2][7] Parrino, Noland's friend and also a participant in the exhibition, described this as akin to "a serial killer disposing of a body."[81]

In 2003 Noland's work The Big Slide (1989) was included in the Italian pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale.[82] The same year, David Zwirner Gallery attempted to include a work by Noland in a group exhibition in New York, but she requested its removal when she learned about the show.[83] In 2004 she wrote an essay for Artforum on artist Andy Warhol, whose work she admires.[84]

Noland's extended absence from the art world spurred several galleries to attempt to mount unauthorized exhibitions,[7] including a show at the nonprofit gallery Triple Candie in 2006 comprising inexact remakes of Noland's work made by other artists.[85] Art critics in New York reacted negatively to the show, with Jerry Saltz calling the exhibition "an aesthetic act of karaoke, identify theft, [and] body snatching."[86] Writing in The New York Times, critic Ken Johnson called the Triple Candie show "confused, confusing and duplicitous."[85]

2010s: Artwork "disavowals," legal proceedings, retrospective

[edit]Prior to an auction at Sotheby's in March 2012 that was to include several works by Noland, the auction house removed Noland's aluminum print Cowboys Milking (1990) from the sale after she "disavowed" the work.[87] Noland had visited the auction house to view the condition of several works set to be sold, and deemed Cowboys Milking to be damaged beyond repair.[7] The work's owner, gallerist Marc Jancou, later sued both Noland and the auction house for a combined $26 million, but a judge dismissed the suit.[7]

Also in 2012, galleries and art dealers attempting to exhibit Noland's work for sale began posting disclaimers to inform audiences that the artist had not been involved with or agreed to the exhibition of her work.[88] The first such disclaimer, at the artist's request,[7] accompanied an exhibition of her work organized by dealer Christopher D’Amelio at the Art Basel art fair and stated that Noland did not think D'Amelio was "an expert or authority on her artwork, did not select the artwork being displayed in this exhibition, and in no way endorses Mr D'Amelio's arrangement of her work."[89]

In 2013, art dealer Larry Gagosian attempted to organize an exhibition of Noland's work at his eponymous gallery with curator Francesco Bonami.[90] In the text accompanying an interview with Noland, author Sarah Thornton wrote that Noland had responded to the gallery's outreach by threatening to shoot Gagosian if he followed through on the exhibition, saying that she did not want to be "saved from obscurity."[91] She added that "Artists go to Gagosian to die. It's like an elephant graveyard."[92] When asked a decade later about the alleged incident, Noland said only that "I wasn’t interested in having an unauthorized show."[7] Noland also told Thornton that handling the issue of non-approved exhibitions or restoration of her work was "a full-time thing" that had impacted her time and ability to make new art.[93] Noland's interview with Thornton - the artist's first in over a decade[2] - was itself accompanied by a disclaimer requested by Noland that said the artist had not approved the text.[94] In 2014, another disclaimer was posted at an exhibition featuring Noland's work at the Brant Foundation, saying that Noland “reserves her attention for projects of her own choosing” and “hasn’t given her approval or blessing to this show.”[95]

In June 2015, Ohio-based art collector Scott Mueller filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of New York seeking to reverse his 2014 purchase of Noland's sculpture Log Cabin (1990) for $1.4 million; he claimed that Noland had "disavowed" the work by not approving the extensive restoration of the piece.[87] The artist disavowed her sculpture after its sale to Mueller because she believed the work had been restored "beyond recognition."[96] This restoration occurred after a long-term loan to Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum in Aachen, Germany, where the logs had deteriorated from 10 years of outdoor exposure. A conservator was consulted and hired to complete the restoration in Germany, where all the decayed wood was replaced by logs obtained from the same Montana source as the originals.[97] Noland, who believes she should have been consulted about this, felt the extensively restored piece was essentially recreated, and was therefore an unauthorized copy of the original, violating her copyright protections as outlined in the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA).[98] Mueller's lawsuit was dismissed in 2016.[96] After Noland filed her own lawsuit claiming damages under VARA, she became involved in increasingly complicated legal battles over the restoration of Log Cabin and the application of copyright law to the materials used in her sculpture, German vs. US laws, and her rights to copyright as a living artist.[99] The United States Copyright Office later ruled that Log Cabin was ineligible for copyright protection because, as a simple wooden structure, the work "lacked sufficient original or creative authorship" as defined by U.S. copyright law, and the office "explicitly disregarded Noland's 'conceptual choices' in creating the work."[100] Noland's lawsuit was also later dismissed, with courts deciding that her rights had not been violated.[7]

In November 2017 gallery Venus Over Manhattan opened an exhibition of historical work by Noland and Alexander Calder, staged with Noland's permission and participation.[101] The exhibition, Kinetics of Violence: Alexander Calder + Cady Noland, juxtaposed two works each by the artists.[102] Noland exhibited Corral Gates (1989), a series of gates meant for livestock decorated with saddles and bullets,[101] and Gibbet (1993-1994), a stocks sculpture fitted with an American flag covering its surface.[102] Critic Andreas Petrossiants wrote in The Brooklyn Rail that the pairing of Noland and Calder had the effect of "re-politicizing a thoroughly de-politicized Calder," reminding audiences of the latter artist's sustained engagement with anti-war and anti-fascist politics.[101]

Following nearly two decades of little public activity aside from her high-profile legal disputes, Noland staged her first ever museum retrospective exhibition in 2018 at the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt.[103] The curator, museum director Susanne Pfeffer, said she was able to organize the show after convincing a mutual acquaintance to give her Noland's phone number and meeting her at a café in New York.[7] Noland has a fear of flying and was unable to visit the museum to plan for the exhibition, so Pfeffer visited New York every three weeks for a year to plan the show with scale models of the gallery spaces;[7] Pfeffer said "it was and still is a very intense and close collaboration."[104] The artist's work was installed in every gallery in the museum, often in spaces not usually used for displaying art like hallways, corners, and on walls high above eye level.[105] In addition to work from every era of Noland's practice, the exhibition included works by a range of other artists from the museum's collection selected by Noland, including Michael Asher, Joseph Beuys, Bill Bollinger, Claes Oldenburg, Parrino, Charlotte Posenenske, Sturtevant, Andy Warhol, Franz West, and Noland's father Kenneth.[106] Two permanent installations in the museum by Beuys and Oldenburg were sealed off with a wall to prevent viewing; Pfeffer called this decision "practical" as the works are immovable and did not fit in the theme of the show, but critic Leah Pires interpreted the gesture as "a delicious power play, especially coming from two women."[107] The retrospective was broadly acclaimed in German and international media.[108][109][110][111][104][112] Several publications included the show in lists of the best art exhibitions of 2018 and 2019.[113][114][115]

Noland also agreed to participate in a group exhibition in October 2019, curated by artist Paul Pfeiffer for Bortolami gallery, staged in an empty bank at Washington's Watergate complex.[116] The exhibition included a chain-link fence sculpture by Noland - Institutional Field (1991) - that was placed flat on the gallery floor.[117]

2020s: Return to exhibiting new work

[edit]In 2021, Noland exhibited new work in New York for the first time in over twenty years.[7] Her exhibition Cady Noland: THE CLIP-ON METHOD at Galerie Buchholz debuted four a-frame barricade sculptures and two chain-link fence sculptures, including one fence blocking the gallery's only window.[118] She also covered the gallery floor with a gray carpet and showed several silk screen works from the 1990s featuring reproductions of descriptions from police officer training manuals of supposedly justified violent policing techniques.[119] Several critics noted that the freshly installed industrial carpet emitted a distinct chemical smell in the gallery.[120][121] The exhibition coincided with the self-publication of an artist's book of the same name documenting many of Noland's works, exhibitions, and writings, along with a range of sociological essays and articles she selected.[8] Writing in The New Yorker, Johanna Fateman said the exhibition displayed an "oppressive mood of sordid Americana – the carceral harmonizing with the corporate."[121]

Noland presented new work again in 2023 at a solo exhibition with Gagosian Gallery in New York, a decade after refusing Gagosian's earlier attempts to stage an exhibition of her work.[122] The exhibition, staged in a small gallery space on the Upper East Side, included over a dozen new untitled works by Noland made from objects like filing cabinets, lucite tables, beer cans, bullets, police badges, and inert grenades, including several small objects encased in clear acrylic cubes,[7] in addition to tape and vinyl markings on the gallery floor.[122] Noland also exhibited a single historical work, Untitled (1986), comprising a metal walker adorned with leather gloves, a holster, and other objects.[122] Critic Isabel Ling wrote that the tape on the floor made the installation resemble a crime scene and said the pieces on view, much smaller than many of Noland's earlier installation works, represented "a turn toward the interior."[123] The entirety of the exhibition was purchased by the private museum Glenstone.[7]

In 2024 Glenstone announced the opening of a survey of Noland's work, created "in collaboration with the artist," according to the museum.[7][124] The exhibition opened in October 2024 and is on view until February 2025.[125] The show includes work from Glenstone's collection from every era of Noland's practice, including all the works she exhibited at Gagosian in 2023.[124][125] Additionally, Noland installed several new objects around her most recent work, including industrial plastic pallets, a cast aluminum box branded with a Pinkerton logo, and a metal platform with a barcode identifying it as belonging to an Amazon warehouse.[124]

Analysis and themes

[edit]Critics and art historians have used several terms to label Noland’s style and artistic practice in relation to other artists working both before and during her time. Artist and writer Olivier Mosset said in 1989 that Noland’s work was part of a second, less restrained generation of the Neo-geo (Neo-Geometric Conceptualism) movement.[126] Mosset wrote that the layout of Noland's works has an "apparent casualness" that signals a questioning of the importance or centrality of the notion of the art object.[127] Curator Ralph Rugoff included Noland's work in an exhibition in 1990 exploring what he called "pathetic art,"[128] which he described as art that "makes failure its medium;" critics also later termed this "abject art."[129] Critic Jack Bankowsky used the term “slack art” to describe Noland's work in Artforum in 1991, which he said was art that “depends on consciously courted chaos."[130] Bankowksy identified Noland’s piece Dirt Corral (1984-1985) - a work comprised of several decorative furniture panels arranged together on the floor[46] - as the work that marked the beginning of this stylistic movement, which he wrote also included artists like Karen Kilimnik and Jack Pierson.[130] Roberta Smith, writing in The New York Times, called Noland "a leading practitioner of a kind of 90's Process art sometimes known as scatter art."[67] Art historian and critic Bruce Hainley has pushed back on descriptions of Noland's work as "scatter art" or "pathetic art," writing that her work was "mistaken" as such in the 1990s but that her retrospective in 2018 reframed her as "an unusually consistent maker of discrete objects."[131]

Charles Hagen, writing in the Times in 1991, labeled Noland's work an example of a "recent resurgence in what might be called hardware art," grouping Noland with artists including Ashley Bickerton and Wolfgang Staehle.[132] Critic Lane Relyea, writing in 1991, included Noland among a group of artists making work in the legacy of Pop art but with a pessimistic tone, which he called "Neo-pop."[133] Critics have also pointed to the scale of and industrial materials used in many of her works as examples of her utilization of the stylistic hallmarks of minimalism, often deployed for a purposefully sinister or controlling effect.[134][135][136][137] Writers have also labeled her work an example of post-minimalist sculpture and installation.[138][139]

Many critics have identified the collapse of the American Dream as a core theme in Noland's work;[140][141][142][143] curator Christian Rattemeyer labeled this the "American Nightmare."[144] Noland has said she explores aspects of American culture she considers uniquely toxic, including status seeking, celebrity, violence, and death, all of which fit into what she has called "a meta-game" underpinning American society, the rules and existence of which she says are kept from most people, particularly minorities.[145] Several critics have also remarked on Noland's thematic focus on a specific geographic and socioeconomic subsection of American society, namely rural working class communities.[146][147][148] She has also extensively utilized American flags in her work; multiple critics have compared her use of the flag to that of Jasper Johns, writing that Noland's deployment of the symbol, often crumpled, torn, or otherwise sullied, represents a larger rejection of the flag's value as a cultural icon than what Johns achieved with his various iterations on Flag.[149][150] Others have compared Noland's examination of American culture and iconography to Robert Frank's photography book The Americans,[151][152] and to the work of American short story writers like Raymond Carver[153] and William S. Burroughs.[154]

Critics and art historians have written that Noland's work also deals with themes of physical and mental restriction, often using metal, fencing, and barriers to create feelings of combining or decoupling.[155][156][157] Her use of medical devices like IVs, walkers, and sight canes has also been noted as exploring similar themes of restriction and distress.[158][159] Writer Jim Lewis described her medium as "borders and paths: on the one hand fences, boundaries, confines, gates, and barriers; and on the other their violation..."[160] Noland has connected her use of architectural interventions like gates and barriers to her exploration of psychopathology; she has said she aims to explore what it means to treat people like objects by guiding or restricting their movements, in the same way she says psychopaths view others as objects for use and eventual discard.[161][162] She told writer Jeanne Siegel in 1989 that "A good way to decipher my pieces is to look at how they 'behave.'"[163] Noland has on several occasions discussed the use and importance of metal in her work,[164] saying in an interview in 1994 that "Metal is a major thing, and a major thing to waste."[165] Writing in October in 1995, critic Liz Kotz suggested that Noland's thematic examinations of confinement and aggression could be viewed through a feminist lens "as very interesting work about gender," although critics at the time generally did not see Noland's work as such.[166]

Violence, both interpersonal and accidental, has been identified as another key theme in Noland's work;[167][168][169][170] she has often used images of murder, violent accidents, and weaponry, and has incorporated a wide array of physical weapons into her sculptures and installations, including billy clubs, grenades, guns, and bullets.[11][123] In her essay "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil" she wrote that the supposed ideal end of the "meta-game" in American society is an "action death," or death in a violent accident of some kind.[171] Noland's friend and fellow artist Steven Parrino wrote that Noland's "subjects are not social anthropology but clues to herself," adding that several works were inspired by Noland's own fears: Crashed Car was inspired by a childhood memory of a car crash; Plane Crash stemmed from her fear of flying; and The Family and the SLA that kidnapped Patty Hearst was based on her fear of cults.[172] Critic Martin Herbert suggested that Noland "was not playing with her subject matter but angrily terrified of it, and her anger and fear were channeled into articulacy."[173] Humiliation and shame are also recurring themes in Noland's work, with critics pointing to her stocks sculptures and photographic silk screen work featuring tabloid imagery as examples.[174][175]

By using press photographs for her silk screen works, critics have posited that she is reframing the images and drawing attention to the structures involved in reproducing photographs or information.[176][177] Noland often reorients the texts and images she uses in these works, flipping, inverting, or turning on their sides the photographs and excerpts she appropriates, an effect Hainley called "discombobulations."[3] Writing in 1996, critic Christopher Hume said Noland "turns media images into shiny sculpted logos."[178] Others have written that these works, often featuring notable or notorious figures or archetypes from American society who have become famous through scandal or crime, explore a distinctly American form of celebrity and media culture, showcasing the ways American media elevates, commodifies, and discards specific people who have publicly transgressed in some way.[179][180][181] Writing in Parachute, critic Abbie Weinberg proposed that "the flatness" of her silkscreen cut-out works "is a metaphor for the two-dimensionality of Western culture's iconography."[182] Similarly, curator Francesco Bonami wrote that "the flat form" of her cut-out works "alludes to the undercurrent of violence concealed within one-dimensional, stereotypical images of America and its myths."[183] Additionally, Noland's use of silk screened appropriated media images has been widely compared to Andy Warhol's practice and techniques. A broad array of critics and art historians have cited Warhol's work as a direct precedent to Noland's.[184][185][186][187]

Several critics have suggested that Noland's legal disputes surrounding the sale, restoration, and treatment of various works, along with her nearly two-decade long self-imposed distance from the traditional gallery ecosystem, were themselves a form of artistic statement and communication.[188][189][190][191] Writing for T: The New York Times Style Magazine in 2019, Zoë Lescaze posited, "She has become known as the art world’s boogeyman, but she might be its conscience."[192] Some critics have proposed that Noland's artwork disavowals and longtime rejection of art world institutions are a rejection of the art market itself;[193][194][195] critic Seph Rodney labeled her actions "(performance) art as poison pill,"[196] while art historian Frazer Ward described them as an "attack on the market."[197] Multiple writers have noted that Noland's seeming disappearance from producing or exhibiting new work in the 2000s and 2010s had, in effect, garnered her wider critical acclaim and caused increases in secondary market prices for her work, a function of the art market's economic model of scarcity and exclusivity.[198][199]

Noland's legal disputes surrounding the handling of her work have also been extensively discussed by critics and academics in the contexts of art authentication,[200][201] the limits of copyrightability in the United States,[202][203] and the scope of artists' moral rights under U.S. law.[204][205]

Influence and legacy

[edit]Numerous critics, art historians, and artists have cited Noland as a significant influence on contemporary art beginning in the 1990s. Critic Roberta Smith has written several times about Noland's influence, saying that she had helped define a set of "fashionable parameters" for installation artists of the 1990s, which Smith described as "junk and juxtaposition - the devalued and the unexpected."[206] Smith wrote in 2002 that Noland's exhibition in 1989 at American Fine Arts Co. marked "one of the earliest signs of change" in contemporary art's shift from the stylistic trends of the 1980s, saying that "Noland's contribution is unquestionable, but she is becoming even more mythic in her absence" from the commercial art world.[207] Critic Jerry Saltz, writing in The Village Voice in 2006, said Noland was "the crucial link between late-1980s commodity art and much that has followed."[208]

In 2007, New York magazine called Noland "The most radical artist of the eighties" and said that her work had "predicted a hundred other artists."[209] Critics have cited a wide range of artists as working in Noland's stylistic legacy, including Jesse Darling, Diamond Stingily, Cameron Rowland, Andra Ursuța,[2] Kelley Walker, Nate Lowman, Banks Violette,[210] Rachel Harrison,[211] Josephine Meckseper,[212] Steven Shearer,[213] Anna Sew Hoy,[214] Liz Larner,[215] Jon Kessler,[216] Sam Durant, Matt Keegan, Helen Marten, Bozidar Brazda,[217] and the collaborative work of Joe Bradley and Eunice Kim.[210] Artists including Mary Heilmann,[218] Johannes Kahrs,[219] Cosima von Bonin,[220] Meckseper, and Brazda have all themselves cited Noland as an inspiration or influence on their work.[221]

Curator and professor Bill Arning, speaking in 2018, said that his students "shero worship her. The idea of someone who is that firm in her decision making, [who] can say no to all the cash and prizes."[2]

Personal life

[edit]Noland has never publicly spoken at length or released information about her early life, biography, or personal life.[222] There are only two known public photographs of the artist as an adult; in one of the images, taken at Documenta in 1992, she is covering her face with her hands.[7] On several occasions when requested to provide photos of herself for publications, she has submitted images of herself as a child in lieu of more current photographs.[3][7]

Art market

[edit]In 2011, Noland's work set the then-record for the highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living woman when Oozewald (1989), a silk screen work depicting Lee Harvey Oswald, sold at Sotheby's for $6.6 million.[2] Noland's red silk screen on aluminum, Bluewald (1989), also depicting Oswald, sold for $9.8 million at Christie's in May 2015, setting a new auction record for the artist's work.[223]

Exhibition history

[edit]Noland has staged numerous solo exhibitions in the United States and internationally. She staged a large number of shows in the late 1980s and early-mid 1990s, but stopped exhibiting for nearly 20 years beginning in the early 2000s. Noland's notable solo exhibitions include White Room: Cady Noland (1988), White Columns, New York;[13] New West-Old West (1990), Luhring Augustine Hetzler, Los Angeles;[39] Cady Noland (1994), Paula Cooper Gallery, New York;[60] Cady Noland (2018-2019), Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, the artist's first retrospective exhibition;[224] Cady Noland: THE CLIP-ON METHOD (2021), Galerie Buchholz, New York, the artist's first exhibition of new work in the United States in over twenty years;[120] and Cady Noland (2023), Gagosian Gallery, New York.[122]

Noland has also participated in a wide list of notable group exhibitions, including the 44th[2] and 50th Venice Biennale[82] (1990, 2003); Whitney Biennial (1991);[47] and Documenta 9 (1992).[33]

Notable works in public collections

[edit]- The American Trip (1988), Museum of Modern Art, New York[225]

- The Big Slide (1989), Art Institute of Chicago[226]

- Celebrity Trash Spill (1989), Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz[227]

- Deep Social Space (1989), Museum Brandhorst, Munich[228]

- Oozewald (1989), Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland;[229] and Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp[230]

- Tanya as a Bandit (1989), Museum Brandhorst, Munich;[231] Museum of Modern Art, New York;[232] and Whitney Museum, New York[233]

- This Piece Has No Title Yet (1989), Rubell Museum, Miami/Washington, D.C.[234]

- Bluewald (1989-1990), Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut[235]

- Sham Death (1993-1994), The Broad, Los Angeles[236]

- Publyck Sculpture (1994), Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland[229]

- 4 in One Sculpture (1998), Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York[237]

- Untitled (2008), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis[238]

Citations and references

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Schjeldahl (1990), p. 93, quoted in Rondeau & Miller-Keller (1996), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Russeth (2018)

- ^ a b c d e f B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ Hughes (2015), p. 529, cited in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ Lewin (1988), quoted in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ a b Stillman (2010), p. 35

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Halperin (2024)

- ^ a b Merjian, Ara H. (17 August 2021). "Piecing together Cady Noland's 'THE CLIP-ON METHOD'". Frieze. OCLC 32711926. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 45, quoted in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 326

- ^ a b Siegel (1989), p. 45

- ^ Stillman (2010), pp. 35–36

- ^ a b "White Room: Cady Noland". White Columns. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ a b Drent, Henk (21 November 1988). "'Jonge Amerikaanse kunstenaars zijn extreem succesgericht'". Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). p. 9. OCLC 12121438. Retrieved 18 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b Tegenbosch, Pietje (7 April 1995). "Noland plukt beelden uit alledaagse werkelijkheid: Foto's uit de roddelbladen en persarchieven". Het Parool (in Dutch). p. 11. OCLC 463292576. Retrieved 18 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Voorkeur galeries". NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). 24 November 1988. p. 5. OCLC 924444281. Retrieved 12 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b Smith (1989)

- ^ Liebmann (2018)

- ^ a b Salvioni (1989)

- ^ a b c Faust (1989), p. 92

- ^ "Art". Goings On About Town. The New Yorker. Vol. 65, no. 12. 8 May 1989. p. 13. OCLC 320541675.

- ^ Siegel (1989), pp. 43–44

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 44

- ^ Smith (1989): "Ms. Noland's use of gleaming, lightweight metals supplies a necessary visual consistency to the seemingly chaotic proceedings of her art..."

- ^ Salvioni (1989): "...it is shiny metallic and new, but lower class and violent too. [...] The accumulation of stuff Noland makes her art out of has a common, metallically visual effect."

- ^ Liebmann (2018): "But, whether simple or complex, there is a formal leitmotiv uniting all this miscellanea: the mean, bluish glint of steel. Noland shows for cold metal some of the inventive aplomb that the German artist Martin Kippenberger has for softer, but equally mundane, building materials like plywood and particle board."

- ^ Olijnyk, Michael; et al. (November–December 1998). "20 Years of dialogue". Dialogue. Vol. 21, no. 5. p. 29. OCLC 4730991. ProQuest 232980173.

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 44, quoted in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ a b c Binlot, Ann (3 December 2019). "Vanity Fair, Genesis, and the Rubell Museum Kick Off Miami Art Week". Vanity Fair. OCLC 8356733. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Lannacci, Anthony (February 1990). "Cady Noland". Artforum. Vol. 28, no. 6. p. 150. OCLC 20458258. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b Rubinstein (1990)

- ^ a b c d Schjeldahl (1990), p. 93

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stillman (2010), p. 36

- ^ Noland (1994), p. 77, quoted in Pires (2019), p. 85

- ^ Noland (2003), p. 196, cited in Herbert (2016), p. 103

- ^ a b Noland (2003), p. 196

- ^ Nickas, Bob (8 November 2012). "Komplaint Dept. – Giving Up the Ghost: Andy Warhol Visits the Warhol Show at the Met". Vice News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Wallach, Amei (4 June 1990). "What's Happening Next: The signal out of the Venice Biennale is: Tighten your seat belts, the rules have all changed". Newsday. p. 92. OCLC 5371847. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f McKenna, Kristine (24 July 1990). "ART REVIEWS: Every Litter Bit Helps to Understand 'New West-Old West'". Los Angeles Times. sec. F, p. 5. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 281142701. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Noland (1994), p. 79

- ^ Noland (1994), p. 79, quoted in Russeth (2018)

- ^ del Pesco, Joseph (27 July 2020). "How a New Kind of Artist Contract Could Provide a Simple, Effective Way to Redistribute the Art Market's Wealth". Artnet News. OCLC 959715797. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ van Haaften-Schick, Lauren (March 2021). "Power Moves: How can artist contracts address economic injustice? Sign on the Dotted Line". Frieze. No. 217. p. 24. OCLC 32711926. EBSCOhost 149385480. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ a b Knight, Christopher (14 August 1990). "ART REVIEWS: The Pathetic Aesthetic: Making Do With What Is". Los Angeles Times. sec. F, p. 8. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 281057827. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ Wilson (2004), pp. 117–118

- ^ a b Wilson (2004), p. 118

- ^ a b c Kimmelman, Michael (19 April 1991). "Review/Art; At the Whitney, A Biennial That's Eager to Please". The New York Times. sec. C, p. 1. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ a b McEvilley, Thomas (Summer 1991). "New York: The Whitney Biennial". Artforum. Vol. 21, no. 10. p. 100. OCLC 20458258. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Knight, Christopher (28 April 1991). "ART REVIEW: Four Floors of Evolution: The '91 Whitney Biennial divvies up painters, sculptors and photographers from the '50s to the '90s floor by floor--and the curators' conceit works". Los Angeles Times. sec. F, p. 3. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 281425574. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Johnson (1991), p. 46

- ^ Canning, Susan (July 1991). "Whitney Biennial". Art Papers. Vol. 15, no. 4. p. 60. OCLC 7219444. EBSCOhost 49166264.

- ^ Buck, Louisa (July–August 1991). "Balance or baggage? Whitney Biennial". Women's Art Magazine. No. 41. OCLC 24481379. Gale A262690771.

- ^ Danto, Arthur (1998). "The 1991 Whitney Biennial". Wake of Art: Criticism, Philosophy, and the Ends of Taste (1st ed.). Amsterdam: G+B Arts International. p. 165. ISBN 9789057013010. OCLC 39754928.

- ^ "Cady Noland". MOCA. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 26 October 2024. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b Pagel, David (15 May 1992). "ART REVIEWS: Diane Arbus: Pictures From the Institutions". Los Angeles Times. sec. F, p. 16. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 281565498. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Knight, Christopher (12 July 1992). "ART: REVIEW: Look for the American Label: Global pluralism may be the theme of Documenta 9, the latest extravaganza at Kassel, Germany, but the show gets its bite from American artists". Los Angeles Times. sec. F, p. 3. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 281642509. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Zacharopoulos (2022), p. 37

- ^ Zacharopoulos (2022), p. 39

- ^ Madoff, Steven Henry (2 June 2002). "Artists document what art expo means to them and their craft". The New York Times. sec. 2, p. 29. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Roberta (8 April 1994). "Review/Art: Dark Side of the American Psyche". The New York Times. sec. C, p. 23. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Rondeau & Miller-Keller (1996), p. 6

- ^ Parrino (2005), p. 4, quoted in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ Wakefield (1994), p. 89

- ^ Bussel, David (June–August 1994). "Cady Noland". Frieze. No. 17. pp. 58–59. OCLC 32711926. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Weber (1994), p. 159

- ^ Schwartz, Ineke (27 March 1995). "Cady Noland wordt achterhaald door het succes van haar eigen werk: Als het op Warhol gaat lijken, wist ze het uit". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). p. 9. OCLC 781575477. Retrieved 18 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b c Smith, Roberta (12 July 1996). "ART REVIEW; In Connecticut, the Old Meets the New". The New York Times. sec. C, p. 25. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 31 December 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Rondeau & Miller-Keller (1996), pp. 4, 7, 9–10

- ^ Zimmer, William (4 August 1996). "Veterans With Family Ties". The New York Times. sec. CN, p. 14. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 31 December 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ McNally, Owen (24 June 1996). "A Spectacle of Pop Culture Made by Media". Hartford Courant. p. E1. OCLC 8807834. ProQuest 255736908.

- ^ Monk (1996), p. 22

- ^ Smith, Roberta (6 August 1999). "ART IN REVIEW; Anni Albers, Robert Beck, Cady Noland, Joan Semmel, Nancy Shaver". The New York Times. sec. E, p. 40. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d Parrino (2005), p. 5

- ^ Williams (1999)

- ^ Parrino (2005), p. 5, quoted in B. Hainley (2019)

- ^ Saltz (1999): "Initially perplexing, this unlikely congregation mutates into a disturbing pictograph, a sociopathic rebus that spells Scary American Family. [...] Cady Noland's silver-painted cardboard stock in the middle of the room radiates discipline and violence."

- ^ Schjeldahl (1999), p. 86, quoted in B. Hainley (2019): "This show suggests to me a metaphorical family romance in which Beck’s tape evokes a traumatizing dad and Albers’s textile an exacting mom. The other works at Marks complete the analogy: Cady Noland as a sister in misery; Joan Semmel as a raffishly louche aunt; and Nancy Shaver as an exemplary older cousin."

- ^ Williams (1999): "Made of silver-painted cardboard, it resembled a streamlined 17th-century pillory or stock, an instrument of punishment which was originally used to publicly humiliate petty offenders. [...] this piece functioned as a sort of sieve through which visual access flowed."

- ^ a b c Vogel (1999)

- ^ Parrino (2005), p. 8

- ^ Parrino (2005), p. 8, quoted in Russeth (2018) and Halperin (2024)

- ^ a b Nochlin, Linda; Rothkopf, Scott; Griffin, Tim (September 2003). "Pictures of an Exhibition: The 50th Venice Biennale". Artforum. Vol. 42, no. 1. OCLC 20458258. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Rimanelli, David (September 2003). "Entries: David Rimanelli". Artforum. Vol. 42, no. 1. OCLC 20458258. ProQuest 214345911. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Noland (2004), cited in Halperin (2024)

- ^ a b Johnson, Ken (12 May 2006). "Art in Review; 'Cady Noland Approximately'". The New York Times. sec. E, p. 32. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Saltz (2006), quoted in Thornton (2015), p. 328

- ^ a b Gilbert, Laura (25 June 2015). "Did Cady Noland disavow another work?". The Art Newspaper. OCLC 23658809. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015.

- ^ Pires (2019), pp. 84–85

- ^ Gleadell, Colin (11 June 2012). "Art Basel 2012: the future's orange". The Daily Telegraph. OCLC 6412514. Gale A298799461. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 328, cited in Halperin (2024)

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 328, quoted in Halperin (2024)

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 328

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 328, quoted in Kinsella (2015) and Halperin (2024)

- ^ Thornton (2015), p. 325, cited in Russeth (2018) and Halperin (2024)

- ^ Russeth, Andrew (10 November 2014). "Cady Noland Works, and a New Disclaimer, Appear at the Brant Foundation". ARTnews. OCLC 2392716. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ a b Kinsella, Eileen (3 June 2020). "Cady Noland Said a Collector Restored Her Log Cabin Sculpture Beyond Recognition. A Judge Has Thrown Out Her Lawsuit—for the Third Time". Artnet News. OCLC 959715797. Archived from the original on 26 July 2024. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Kinsella (2015)

- ^ Kaplan, Isaac (21 July 2017). "Cady Noland Sues Collector and Galleries to Destroy Artwork "Copy"". Artsy. OCLC 893909467. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Halperin, Julia (5 April 2018). "Art Dealers Strike Back at Cady Noland in an Increasingly Philosophical Legal Dispute About a Restored Sculpture". Artnet News. OCLC 959715797. Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Frye (2021), p. 196

- ^ a b c Petrossiants (2018).

- ^ a b Gibbons, James (16 December 2017). "The Violent Forms of Alexander Calder And Cady Noland". Hyperallergic. OCLC 881810209. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Pires (2019), p. 83

- ^ a b Herbert, Martin (15 March 2019). "Cady Noland Says Yes". ArtReview. OCLC 863456905. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Steer (2019), p. 26

- ^ Steer (2019), p. 27

- ^ Pires (2019), p. 84

- ^ Maak, Niklas (7 November 2018). "Amerikanisches Requiem mit Weißwandreifen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). OCLC 1245573964. ProQuest 2130182380. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Nedo, Kito (27 November 2018). "Amerikanische Angst". Die Tageszeitung (in German). OCLC 33446024. ProQuest 2137505860. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Wagner, Andrew (January 2019). "Cady Noland, MMK Frankfurt". The White Review. OCLC 1419332387. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Albrethsen (2019)

- ^ Hafner, Hans-Jürgen (Spring 2019). "Cady Noland". Springerin (in German). No. 2. OCLC 260048804. ProQuest 2245413873.

- ^ Herbert, Martin; et al. (8 January 2019). "Best of 2018: editor's picks". ArtReview. OCLC 557734373. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Barry, Robert (14 December 2019). "2019 In Art: Quietus Writers Pick The Year's Best Exhibitions". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Bang, Margaux (5 June 2020). "These are the 10 Most Impactful Art Exhibitions of 2019". L'Officiel USA. OCLC 1461004385. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Freeman, Nate (29 October 2019). "Just in Time for Trump's Impeachment, the Watergate Is Back in the Spotlight—as a Place to Show Contemporary Art". Artnet News. OCLC 959715797. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Ables, Kelsey (14 November 2019). "World-class conceptual art pops up in a vacant bank at the Watergate". The Washington Post. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Avgikos (2021)

- ^ Moffitt, Evan (November–December 2021). "Cady Noland: Galerie Buchholz, New York". Art in America. Vol. 109, no. 6. p. 95. OCLC 1121298647. EBSCOhost 153147706. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ a b Schwendener, Martha; Farago, Jason (9 July 2021). "Art Gallery Shows to See Right Now". The New York Times. sec. C, p. 12. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ a b Fateman, Johanna (26 July 2021). "Cady Noland". Goings On About Town. The New Yorker. Vol. 97, no. 21. p. 10. OCLC 320541675. EBSCOhost 151444029. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d Greenberger, Alex (19 September 2023). "Reclusive Artist Cady Noland Delivers Another Shock: A Gagosian Show Filled with New Work". ARTnews. OCLC 2392716. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ a b Ling, Isabel (Autumn 2023). "Cady Noland at Gagosian". Spike Art Magazine. No. 77. OCLC 1286852463. Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Greenberger, Alex (7 November 2024). "Cady Noland, an Art World Recluse, Has Officially Come Back into the Fray". ARTnews. OCLC 2392716. Archived from the original on 7 November 2024.

- ^ a b Ostrow, Saul (November 2024). "Cady Noland". The Brooklyn Rail. OCLC 64199099. Archived from the original on 13 November 2024. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Mosset (1989), p. 68

- ^ Mosset (1989), p. 66

- ^ Muchnic, Suzanne (12 February 2006). "Art; As seen in the eye of the beholder". Los Angeles Times. sec. E, p. 44. OCLC 3638237. ProQuest 422056348. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 117

- ^ a b Bankowsky (1991)

- ^ Hainley, Bruce (Summer 2019). "Cady Noland". Artforum. Vol. 57, no. 10. OCLC 20458258. ProQuest 2233065938. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Hagen, Charles (9 August 1991). "Reviews/Art; In New Jersey, Art in Ceramic, in Textiles and Even in Light". The New York Times. sec. C, p. 23. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Singerman, Howard (October 2004). ""Helter Skelter"". Artforum. Vol. 43, no. 2. OCLC 20458258. ProQuest 214343875. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Vogel (1999): "This instability emerges in the vacillation between the work’s status as apparently benign, formal sculpture (with possible origins in seemingly autonomous Minimalist forms) and its identity as an object with authoritarian connotations."

- ^ Jeppesen (2009): "...Cady Noland, whose adaptation of minimalist strategies is used towards an end that is much less subtle in its political implications than most of the artists included in the exhibition."

- ^ Buskirk (2018): "Three tires suspended by chains from a spare support structure evoke a melding of pop art and minimalism that runs through her oeuvre. [...] Her subversion of minimalism is particularly evident in sculptures based on historic pillory devices."

- ^ Avgikos (2021): "The marvel of Noland’s art is that she always sets off an avalanche of imaginative engagements [...] with such elegantly spare means and gestures. In a formal sense, her maneuvers align perfectly with Minimalism, but she amplifies and weaponizes that movement’s inherent machismo and capacity for menace. The result is as much cultural critique as it is deep lamentation."

- ^ Wakefield (1994), p. 89: "Activating the space between these patriotic metal bodies are gallowslike structures, repeating with ominous and pristine newness the swinging tire motif of Manson’s backyard, and a series of Puritan stocks, remade in the cool, formal language of post-Minimalism."

- ^ Anastas (2010), p. 63: "...and the most singular artist to emerge in post-minimal installation, Cady Noland..."

- ^ Relyea (1993), p. 53: "Dream-seekers on an increasingly aimless pilgrimage through a landscape of rapidly decaying symbols - such is the portrait Noland renders of life in America."

- ^ Weinberg (1996): "Like Clark's, [Noland's] art signifies the dissolution of the American Dream, but on a much larger scale. The breadth of her commentary is a function of the shift from anonymity to fame: that an occasional Oklahoman got shot is of far less consequence than that a president did, or that the girl next door became a biker is less frightening than another's voluntary membership in the Manson Family."

- ^ Herbert (2016), p. 104: "What all of this adds up to, insinuates Noland’s fusion of ‘60s Pop, ‘70s scatter art, well-founded ‘80s anxiety, and intermittent invoking of Abraham Lincoln, is the endpoint of a country that couldn’t live up to the ideals upon which it was founded."

- ^ Watlington (2023): "...as ever, Noland’s red, white, and blue sculptures made of resin and refuse chafe at the contradictions between the American dream and the American reality."

- ^ Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397

- ^ Noland (2006), p. 127, quoted in Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397

- ^ R. Smith (1989): "But, with help, the work evoked the struggles and emotional vacancy of the American heartland, especially its southern half, with unusual force."

- ^ Relyea (1993), p. 52: "The incomplete networks of handrails, the gates, the occasional units of chain-link and fencing, all combine to recall the horizons and vistas of big-sky country. The installations feel as archaic as they do ephemeral, like vast landscapes seen from the window of a passing car."

- ^ Lehrer (2023): "Since Noland's show debuted, I have heard people [...] dismiss it as more bourgeois liberal fetishization of the American poor. [...] Where I diverge from this critique is I don't really see urban liberal bourgeois fetishism of Americana to be such a negative thing. Noland is, after all, a wealthy Manhattanite with little authentic exposure to the middle of the country."

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 118: "Inside this one is a rubber chicken, a bungee cord, some beer cans, and, beneath the whole mess, a crumpled American flag. When Jasper Johns drained the color from Old Glory, it retained a glimmer of power; Noland's devastatingly careless gesture dismisses even this vestige of possibility."

- ^ Quin (2019): "Yet another American flag is defiled – Noland shrinks the supposed symbolic value of the Star-Spangled Banner with greater critical intent than Jasper Johns."

- ^ Relyea (1993), pp. 53–54: "[Frank], like Noland, sketched a world centered around the road and its attendant pit-stop culture. [...] Like Noland, Frank documents a social twilight zone, a life spent in permanent exile, oblivion as our Manifest Destiny."

- ^ Knight (1995): "Despite the huge differences, however, a distinctive tone links their work. Frank's ambivalent take on the American Dream reverberates against the neurotic, equally scattered work of Noland, whose birth in 1956 sent her into the world Frank was then describing in his photographic odyssey."

- ^ Johnson (1991), p. 45: "Her sprawling, room-filling installation [...] evokes a certain bleak spirit of tawdry, low rent-Americana that rings a bell of recognition the way the stories of Raymond Carver do."

- ^ Rubinstein (1990): "...Cady Noland nonetheless proved herself possessed of a formal daring and social discontent comparable to that other chronicler of American pathology, William Burroughs."

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 44: "Enclosure can read as protection, confinement, stultification, or entrapment. These pieces, along with others employing open containers, always allow the viewer to see inside. The larger works suggest the corral, the boxing ring, or any arena where activity or spectacle takes place. Enclosure assumes new meanings."

- ^ Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397: "She often uses metallic structures that have a direct and visceral relationship to the body and evoke the acts of joining or separating – crowd barriers, scaffolding joinery, handcuffs."

- ^ Buskirk (2018): "Along with structures made from various configurations of chainlink fencing, they call forth histories of punishment and containment..."

- ^ Albrethsen (2019): "Visitors get their first taste of Noland’s cool approach in the museum lobby: in front of the white circular staircase leading up to the first gallery stands a perfectly ordinary walker [...] It is all too easy to see glimpses of a horrific scene play out before one’s inner eye: blood spilled by an elderly citizen with impaired mobility [...] those who perform poorly (those with Zimmer frames, crutches, and canes – recurring features in several of Noland’s works) are left out before they even enter the race..."

- ^ Watlington (2023): "But for decades, she’s shown assistive devices alongside grenades and can collections, as if she were equating disability with fates as tragic as destitution or death."

- ^ Lewis, Jim (1994). "Wrong". Public Information: Desire, Disaster, Document (Exhibition catalogue). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. p. 24. ISBN 9780918471338. OCLC 30891864.

- ^ Siegel (1989), pp. 42, 44

- ^ Noland (1990), quoted in Rondeau & Miller-Keller (1996), p. 3 and Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 43, quoted in Rondeau & Miller-Keller (1996), p. 4

- ^ Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397: "For Noland metal is a deeply symbolic element; metal stands for permanence in society, its structures of power and authority, something to rebel against. Destruction of metal is transgression."

- ^ Noland (1994), p. 76, quoted in Rattemeyer (2010), p. 397

- ^ Kotz, Liz; et al. (Winter 1995). "A Conversation on Recent Feminist Art Practices". October. 71. Boston: MIT Press: 53, 55. OCLC 47273509. JSTOR 778741.

- ^ Salvioni (1989): "Rather than the outbursts of a deranged, marginal or guerrilla figure, she evokes the homespun violence of the hearth, the bigot underbelly of wholesomeness and good feeling."

- ^ Siegel (1989), p. 45: "Since Noland first started working with found objects in 1983, a primary interest has been in tools of aggression and violence, such as guns, handcuffs, billy clubs."

- ^ Noland (1990): "Practically every piece I have seen of yours in group shows or in your one-person shows projects a sense of violence, via signs of confinement — enclosures, gates, boxes, or the aftermath of accident, murder, fighting, boxing, or as in your recent cut-out and pop-up pieces — bullet holes."

- ^ Petrossiants (2018): "However, her highly calculated appraisals of the semiotic values traceable between commodities and physical forms of control (such as fences, police barricades, and stockades) continue to demonstrate a fierce critique of American violence. Among the more rigorous traits of Noland’s work is the rejection of the implied spectacularity and commodification applied to violence (and to a resistance of that violence), and to the persona of the contemporary artist herself."