cGh physics

cGh physics refers to the historical attempts in physics to unify relativity, gravitation, and quantum mechanics, in particular following the ideas of Matvei Petrovich Bronstein and George Gamow.[1][2] The letters are the standard symbols for the speed of light (c), the gravitational constant (G), and the Planck constant (h).

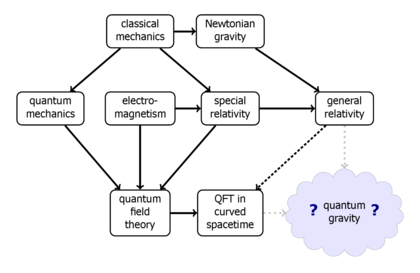

If one considers these three universal constants as the basis for a 3-D coordinate system and envisions a cube, then this pedagogic construction provides a framework, which is referred to as the cGh cube, or physics cube, or cube of theoretical physics (CTP).[3] This cube can be used for organizing major subjects within physics as occupying each of the eight corners.[4][5] The eight corners of the cGh physics cube are:

- Classical mechanics (_, _, _)

- Special relativity (c, _, _), gravitation (_, G, _), quantum mechanics (_, _, h)

- General relativity (c, G, _), quantum field theory (c, _, h), non-relativistic quantum theory with gravity (_, G, h)

- Theory of everything, or relativistic quantum gravity (c, G, h)

Other cGh physics topics include Hawking radiation and black-hole thermodynamics.

While there are several other physical constants, these three are given special consideration because they can be used to define all Planck units and thus all physical quantities.[6] The three constants are therefore used sometimes as a framework for philosophical study and as one of pedagogical patterns.[7]

Overview

[edit]Before the first successful estimate of the speed of light in 1676, it was not known whether light was transmitted instantaneously or not. Because of the tremendously large value of the speed of light—c (i.e. 299,792,458 metres per second in vacuum)—compared to the range of human perceptual response and visual processing, the propagation of light is normally perceived as instantaneous. Hence, the ratio 1/c is sufficiently close to zero that all subsequent differences of calculations in relativistic mechanics are similarly 'invisible' relative to human perception. However, at speeds comparable to the speed of light (c), Lorentz transformation (as per special relativity) produces substantially different results which agree more accurately with (sufficiently precise) experimental measurement. Non-relativistic theory can then be derived by taking the limit as the speed of light tends to infinity—i.e. ignoring terms (in the Taylor expansion) with a factor of 1/c—producing a first-order approximation of the formulae.

The gravitational constant (G) is irrelevant for a system where gravitational forces are negligible. For example, the special theory of relativity is the special case of general relativity in the limit G → 0.

Similarly, in the theories where the effects of quantum mechanics are irrelevant, the value of Planck constant (h) can be neglected. For example, setting h → 0 in the commutation relation of quantum mechanics, the uncertainty in the simultaneous measurement of two conjugate variables tends to zero, approximating quantum mechanics with classical mechanics.

In popular culture

[edit]- George Gamow chose "C. G. H." as the initials of his fictitious character, Mr C. G. H. Tompkins.

References

[edit]- ^ Kragh, Helge (2009). "Relativistic Quantum Mechanics". In Greenberger, Daniel; Hentschel, Klaus; Weinert, Friedel (eds.). Compendium of Quantum Physics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 632–637. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70626-7_184. ISBN 978-3-540-70622-9. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1995). "Review of Matvei Petrovich Bronstein and Soviet Theoretical Physics in the Thirties". Isis. 86 (3): 520. doi:10.1086/357307. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 235090.

- ^ Padmanabhan, Thanu (2015). "The Grand Cube of Theoretical Physics". Sleeping Beauties in Theoretical Physics. Springer. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-3319134420.

- ^ Gorelik, Gennady E. (1992). "First Steps of Quantum Gravity and the Planck Values". Studies in the History of General Relativity. Birkhäuser. pp. 364–379. ISBN 978-0-8176-3479-7. Archived from the original on 2019-04-25. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ^ Wainwright, C.J. "The Physics Cube". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- ^ Duff, Michael; Lev B. Okun; Gabriele Veneziano (2002). "Trialogue on the number of fundamental constants". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2002 (3): 023. arXiv:physics/0110060. Bibcode:2002JHEP...03..023D. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2002/03/023. S2CID 15806354.

- ^ Okun, Lev (1991-01-01). "The fundamental constants of physics". Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 34 (9): 818–826. Bibcode:1991SvPhU..34..818O. doi:10.1070/PU1991v034n09ABEH002475.