Black tree monitor

| Black tree monitor[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Taken at Zoo d'Amnéville | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Varanidae |

| Genus: | Varanus |

| Subgenus: | Hapturosaurus |

| Species: | V. beccarii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus beccarii | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The black tree monitor or Beccari's monitor (Varanus beccarii) is a species of lizard in the family Varanidae. The species is a relatively small member of the family, growing to about 90–120 cm (35–47 in) in total length (including tail). V. beccarii is endemic to the Aru Islands off New Guinea, living in an arboreal habitat. The skin color of adults is completely black, to which one common name refers.[5]

Taxonomy

[edit]Varanus beccarii was first described as Monitor beccarii by Doria, in 1874. Years later, it was classified as a subspecies of the closely related emerald tree monitor (V. prasinus), but a 1991 review of the complex returned V. beccarii to species status, based on its black colouration and keeled scales on the neck.[6][7] Arguably, it should be maintained as a subspecies of the emerald tree monitor based on similarities in their hemipenial structures,[8] but genetic evidence supports their treatment as two different species.[9] Nevertheless, it is part of the V. prasinus species complex.[7]

Etymology

[edit]The generic name Varanus is derived from the Arabic word waral (ورل), which translates as "monitor" in English.[10] Its specific name, beccarii, is named after the Italian explorer Odoardo Beccari.[5][11]

Description

[edit]

Hatchlings and juveniles of V. beccarii are a dark grey in colour, with regular rows of bright yellow-green dots which are particularly noticeable on their backs. As they mature, they turn completely black, losing the colourful dots. Fully grown specimens reach 90–120 cm (35–47 in) in overall length (including tail), with the males slightly larger than the females.

The black tree monitor is generally well adapted for living in trees. Its tail is particularly long, sometimes two-thirds of the overall length, and is used in a prehensile manner to stabilize the animal in the branches.[12] In fact, the tail is used solely for this purpose, as the animal does not evince the defensive tail-lashing behaviour seen in other monitor species. Like other tree monitors, they sport some of the longest and most slender forelimbs of all monitors, which end in elongated digits tipped with large claws and adhesive soles, helping it maintain grip in the trees and catch prey.[13] It also has unusually long teeth for a monitor of its size, which may help it to hold on to prey it catches in the canopy. In the wild, the black tree monitor is reported to be nervous and high-strung; it will flee if threatened, and if handled carelessly, will bite, scratch, and defecate on the offender.[5]

Geographic range and habitat

[edit]V. beccarii is native to the Aru Islands in Indonesia, where it is known locally as waweyaro. It mainly inhabits humid forests and mangrove swamps, being highly arboreal.[14]

Feeding habits

[edit]The black tree monitor is primarily insectivorous, consuming mostly insects but also smaller lizards, small mammals such as shrews, scorpions, eggs, and the nestlings of birds. Like other members of the V. prasinus species complex, they are occasionally seen eating plants in captivity, although the gut contents of wild monitors were not reported to contain plant matter.[7]

In captivity, newly hatched members of the V. prasinus species complex often refuse food for more than two weeks, although force feeding may be recommended before then and until they begin feeding by themselves.[7]

Like other monitor lizards, this species is highly intelligent amongst reptiles, and like others of the V. prasinus species complex, demonstrates complex problem solving abilities, fine motor coordination, and skilled forelimb movements when hunting prey. When it cannot reach prey in tight crevices and hole with its jaws, it will instead extract prey by reaching for it with a forelimb and hooking it out with its claws, allowing it to exploit a wider range of niches.[13]

Predators

[edit]V. beccarii is preyed upon by larger lizards and snakes, as well as foxes, which were introduced to the region. It is also hunted by humans. The hunting threat by humans has gone down, but humans still are a threat.

Reproduction

[edit]Little is known about the reproduction of V. beccarii in the wild. Some report that this species and the rest of the V. prasinus species complex lay their eggs in arboreal termite nests. The surfaces of such nests would be relatively dry, despite very high relative humidity.[7]

Breeding in captivity

[edit]Captive breeding of V. beccarii has been met with mixed success. A common problem is the death of embryos shortly prior to hatching. Possible causes include substrate humidity being too high at least at the last third of the incubation period, nutritional deficits of minerals and vitamins experienced by the mother prior to laying, or an increased gestation period due to lack of suitable sites for laying thus causing thickened eggshells too difficult to be broken to hatch. The study below suggests that the latter is likely not the case as eggshells were not particularly thick compared to the successfully hatched eggs of other tree monitors, and dead embryos had not yet begun attempting to perforate the shell. Incubation with dryer substrate or even suspended without substrate might possibly be better alternatives, to replicate the conditions of termite nests. However failures even when eggs are suspended are reported as well.[7]

Courtship involves the larger male aggressively chasing after the smaller female. Copulation may occur while suspended off the ground, and can last for two hours. Eggs are buried by the female in damp substrate. After hatching, the neonate may refuse food for more than 2 weeks, although force feeding may be recommended before then and until they begin feeding by themselves.[7]

In one study, three eggs were incubated in moistened vermiculite. Incubator humidity was set at 85%, while the relative humidity was 95%. Incubator temperature was 30.5C, and substrate surface temperature was 30C. By 161 days, all three embryos had fully developed, although only one survived, and only after it was forcibly hatched and taken out of the egg, after which it was further incubated with the yolk sac still intact.[7]

A cooked puree was force fed daily, consisting of 25% (by weight) egg, 50% insects, and 25% banana and spinach, plus supplements such as calcium citrate and Herpetal Complete T. This was further supplemented by beef, chicken, and live flies. The plant matter was included to increase levels of carbohydrate and fibers. Growth of the hatchling was slow, and after 147 days only grew from 7.9g to 13.8g, but was otherwise a very active and alert monitor. The study further evaluates that force feeding was likely not necessary as its weight greatly varied even after beginning to feed on its own.[7]

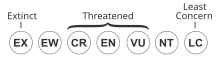

Conservation

[edit]As of 2020, the species V. beccarii is listed as "data deficient" on the IUCN Red List, as insufficient information is available to make reliable population assessments. Deforestation, encroachment by farmland, and the international pet trade are noted as possible current threats.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ "Varanus beccarii ". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ a b Shea, G.; Allison, A.; Tallowin, O. (2016). "Varanus beccarii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T42485677A42485686. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T42485677A42485686.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Doria, Giacomo (1874). "Enumerazione dei rettili raccolti dal Dott. O. Beccari in Amboina alle Isole Aru ed alle Isole Kei durante gli anni 1872-73 ". Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale. 6: 325–357 + Plates XI–XII. (Monitor beccarii, new species, pp. 331-332 + Plate XI, figure a, two views of head). (in Italian).

- ^ Species Varanus beccarii at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ a b c Netherton, John; Badger, David P. (2002). Lizards: A Natural History of Some Uncommon Creatures, Extraordinary Chameleons, Iguanas, Geckos, and More. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-7603-2579-0.

- ^ Sprackland RG (1991). "Taxonomic review of the Varanus prasinus group with descriptions of two new species". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 3 (3): 561–576.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fischer, Dennis (December 2012). "Notes on the Husbandry and Breeding of the Black Tree Monitor Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) beccarii (Doria, 1874)" (PDF). BIAWAK Journal of Varanid Biology and Husbandry. 6: 79–87.

- ^ Böhme W, Ziegler T (1997). "Varanus melinus sp. n., ein neuer Waran aus der V. indicus-Gruppe von den Molukken, Indonesien ". Herpetofauna 19 (111): 26–34.

- ^ Ziegler T, Schmitz A, Koch A, Böhme W (2007). "A review of the subgenus Euprepiosaurus of Varanus (Squamata: Varanidae): morphological and molecular phylogeny, distribution and zoogeography, with an identification key for the members of the V. indicus and the V. prasinus species groups". Zootaxa 1472: 1-28.

- ^ King, Ruth Allen; Pianka, Eric R.; King, Dennis (2004). Varanoid Lizards of the World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 225–229. ISBN 0-253-34366-6.

- ^ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Varanus beccarii, p. 20).

- ^ Cogger, Harold; Zweifel, Richard (1992). Reptiles & Amphibians. Sydney: Weldon Owen. ISBN 0-8317-2786-1.

- ^ a b Mendyk, Robert (September 2011). "Skilled Forelimb Movements and Extractive Foraging in the Arboreal Monitor Lizard Varanus beccarii (Doria, 1874)". Herpetological Review. 42: 343–349.

- ^ Monk, Kathryn A.; De Fretes, Yance (1997). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Periplus Editions. ISBN 962-593-076-0.